True Inspirations

Across The Pond / Mark London Williams

True Inspirations

Across The Pond / Mark London Williams

Not all Presidencies in America are on the precipice of collapse. Kees van Oostrum (above), the DP behind films such as Gettysburg, series like Return to Lonesome Dove or the current The Fosters, as well as director of the film A Perfect Man, has just been re-elected to a third term as President of the ASC.

We were able to catch up with the busy van Oostrum, at least virtually, and ask him some questions about this latest iteration of his current “administration.” In the run up to Cine Gear, we were at J.L. Fisher’s open house, where van Oostrum was on a panel moderated by the ASC’s Bill Bennett, and we asked about his previously-reported response to a question about “who’d invented the first light meter.”

“Vermeer,” replied the Amsterdam-reared van Oostrum, citing the painter who deployed all those groundbreaking techniques used by the Dutch masters for the “capture” and replication of light.

Remembering his answer, we asked him where, in our age of digital cameras and workflows, was the act and art of “light capture” headed now?

“Hopefully to the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam,” he replied, deftly picking up the theme from earlier in the spring, “where besides Vermeer there are a few other fellows that can teach us about color, contrast, framing and, believe it or not, the true application of HDR! To me, HDR - the new sauce of the future - is best explained by visual artists like Rembrandt who use the extended range to create detail in the darkness of the world instead of the brightness.

“Our roles will evolve, and I believe we will continue to shepherd the visual interpretation through our artistry combined with technical knowledge. It’s not always easy, but cinematographers bring a wealth of creative and technical knowledge to their role.”

Not only does that knowledge save both time and money on set and in post, as van Oostrum notes, but it can also inspire subsequent generations of cinematographers.

Which brings us to another new recurring feature in this column. Along with interviewing those behind the lenses of new work for screens both large and small, and our ongoing overview of trade shows, facilities, and the various award shows and festivals, we’re also starting an occasional spotlight where we talk to DPs about the cinematographers who have influenced them.

This began when the great Owen Roizman was given an honorary Oscar last year, and the various contenders and nominees we talked to over the fall and winter, like Janusz Kaminski, kept mentioning the range of Roizman’s work - from documentary grittiness to kinetic action sequences - and the effect it had on their own work. The chats even prompted a rewatching of The French Connection at this end - Roizman’s first Oscar nomination - and we’re still marveling anew how they worked out all that camera placement (including inside Gene Hackman’s car) for the great under-the-train tracks chase.

Now, however, we’ve moved from Oscar to Emmy season - and we’ll have more of the latter as we head into fall - we reached out to DP Alan Jacobsen, of the Emmy-nominated documentary Strong Island, from openly trans filmmaker Yance Ford, about the murder of his then 24 year-old brother by an auto mechanic, for which a Grand Jury declined to bring charges. Ford’s brother, besides being African-American, was also unarmed.

The Netflix-hosted doc found itself nominated for an Oscar, and now is in Emmy’s “Exceptional Merit in Documentary Filmmaking” category. When the great Robby Muller passed recently, Jacobsen took to his FB page to opine on the influence the DP for noted works by Wim Winders, Jim Jarmusch, and others, had had on him:

“We've lost a master. An innovator and true inspiration. I can't tell you how much Mystery Train influenced me at just the right moment when my eyes were being opened seriously to the transformative power of cinematography. That led to the rest of his sublime work with Jarmusch, and then quickly to Wenders and beyond... it was an irreversible slide towards cinematographic art from there. The hook was set. Kings of the Road changed my life. Down By Law. Breaking the Waves... breaking the rules all, and ruining the ‘conventional’ for me forever. The messy, broken, saturated, pointed light of life.”

"I was raised on a Hollywood diet of Spielberg, Lucas, Reiner, etc... when I saw Mystery Train (Dir Jim Jarmusch, DP Robby Muller) it was like "what is THIS!?!" The colors, the contrast, the weird lingering wide shots... I didn't really get why, or how, but it was the beginning of my realization that the photographic mood of a film can be, not just the dressing of, but a fundamental part of the story."

We asked Jacobsen directly, for a few more thoughts on Muller - also noted for shooting films like Saint Jack, for Peter Bogdanovich, and To Live and Die in LA for William Friedkin, and picked up the conversation again with Jarmusch’s Memphis-set, Elvis-themed Mystery Train:

“I saw it at the pivotal moment right as I was about to head to film school. Like everybody entering NYU at that time, I was raised on a Hollywood diet of Spielberg, Lucas, Reiner, etc... when I saw Mystery Train it was like "what is THIS!?!" The colors, the contrast, the weird lingering wide shots... I didn't really get why, or how, but it was the beginning of my curiosity/realization that the photographic mood of a film can be, not just the dressing of, but a fundamental part of the story. This pursuit of the messy, imperfect, intentional mood-as-character has been a goal of mine ever since... “

Of course mood and light are somewhat indistinguishable (when they’re not juxtaposed) - not only during long grey winters, as we’re finding out, but as Jacobsen noted, as an intrinsic part of what a cinematographer does.

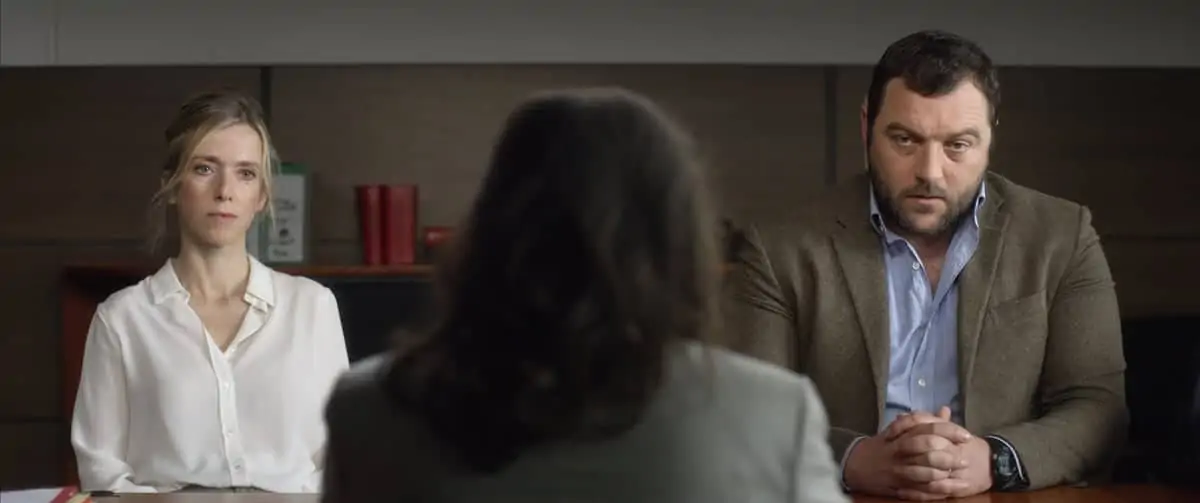

So it was no surprise that when we talked to French DP Nathalie Durand, who shot writer/director Xavier Legrand’s Custody, about a divorcing couple where a father’s seeming grief at being separated from his children is only a thin line away from becoming a stalker - or worse.

The mood in this particular film is closer to a suspense thriller, in terms of pacing, the use of dread and anticipation in shot selection and framing, use of sound, etc.

When the film was having its L.A. opening, we asked Durand about some of her own inspirations and techniques. For the latter, though she and Legrand had considered shooting on film, they “finally agreed on a Red Weapon 6K (actually 5.5K because of the 2.39 format) with a vintage Zeiss GO set of lenses. It was not too sharp and still organic as we wanted.”

They also wanted the freedom digital gear offered because of working with young character actor Thomas Gloria - playing the one under-age child over whom the custody battle is primarily waged - and not wanting to be limited in takes.

There were also a lot of claustrophobic scenes filmed inside the father’s car. And for the finale, set late at night in the mother’s spare apartment, “we decided to start in the dark, very dark because at that time mother and son are focused on sound. And then, step by step as if our eyes get used to the darkness, we see more and more - by opening the stop.”

One might have thought that a Hitchcock DP like John L. Russell or George Barnes would be mentioned, given the building anxiety the film creates, but the first director Durand mentions is Alain Resnais - and his Providence lenser, Ricardo Aronovitch.

The Argentine-born Aronovitch worked from the ‘50s through the ‘00s, with directors including Louis Malle and Ettore Scola, but Durand calls the Dirk Bogarde-starring Providence her “first shock as a young movie spectator. (They used a) quite classical way of lighting but very elegant and it definitively led me to study cinematography.”

She also mentions the great Nestor Almendros, “and his ability to shoot with natural light. I also cannot forget (John) Cassavetes movies for his freedom and the love for actors. And closer to me, I really admire Agnes Godard and her sensitivity.”

Godard has shot a lot for director Claire Denis, and is still working, and her body of work perhaps reminds us that female DPs don’t always have to be a “novelty,” the way they still too often are here.

And as we note, and celebrate the ways different cultures can learn from each other, we swing back around to Mr. van Oostrum, who ended our interview with a similar observation.

We asked him if there was anything he and the ASC were focused on that we hadn’t yet talked about, and he quickly answered “international cooperation. With the globalization of the industry, we need to communicate beyond borders. In this world, there are fantastic developments for collaboration, and it is crucial for anyone in any place of the world to be aware and alert at to what is going on - and be able to look at Vermeer and be inspired to follow his perspective on life.”

Which also brings us back to the Rijksmuseum. One of the most prominent Vermeers there is The Little Street - another great work showing he was, perhaps, a genius cinematographer in his own right, mere centuries before the gear had been invented.

The Philosopher’s Mail website, in their own discussion of the painter’s perspective, notes that The Little Street “is insured for half a billion euros and is the subject of a mountain of learned articles. Yet the painting is curiously – and pointedly – out of synch with its status. Because, above all else, it wants to show us that the ordinary can be very special. The picture says that looking after a simple but beautiful home, cleaning the yard, watching the children, darning cloth – and doing these things faithfully and without despair – is life’s real duty. It is an anti-heroic picture: a weapon against false images of glamour.”

Or perhaps, the “messy, broken, saturated, pointed light of life” that Jacobsen attributes to the work of Muller.

More movies, mentors - and of course Emmys - ahead.

Write in: AcrossthePondBC@gmail.com