Blast Off

Sam McCurdy BSC / Lost In Space

Blast Off

Sam McCurdy BSC / Lost In Space

BY: Adrian Pennington

To reboot 1965 TV series Lost In Space, Netflix returned to the source material, in the form of the novel 'Swiss Family Robinson' published in 1812, and combined it with a visual treatment straight out of the future.

The adventures of a family stranded light years from home on an unknown planet was made in an enjoyably camp Irwin Allen version for CBS and revisited in a 1998 New Line Cinema feature film. The Netflix version, produced by Legendary Television, is set in 2046, spanning ten one-hour episodes and starring Toby Stephens, Molly Parker and Parker Posey, whilst also featuring Taylor Russell, Ignacio Serricchio and Mina Sundwall.

Lost, not knowing where they are, they try to fix their spaceship as they encounter various kinds of mysteries, a robot, and also have to deal with a saboteur in their midst.

Showrunner (executive producer) Zack Estrin tapped director Neil Marshall and cinematographer Sam McCurdy BSC to set the project on its way. McCurdy lensed six instalments of the series, including the pilot, with Emmy-nominee Joel Ransom shooting five episodes to complete the first season. McCurdy had previously shot The Descent and Game of Thrones’ episode “Blackwater” for Marshall.

“Zack very clearly wanted the crux of the story to be about the family, but for the driving force to have a darker, more grown-up undertone,” says McCurdy. “The fundamental story is about a family lost in a difficult, life-threatening situation and how it challenges them and brings them closer together. In every tone reading and visual reference meeting we would mention (James Cameron’s) The Abyss and the Spielbergian world of E.T.”

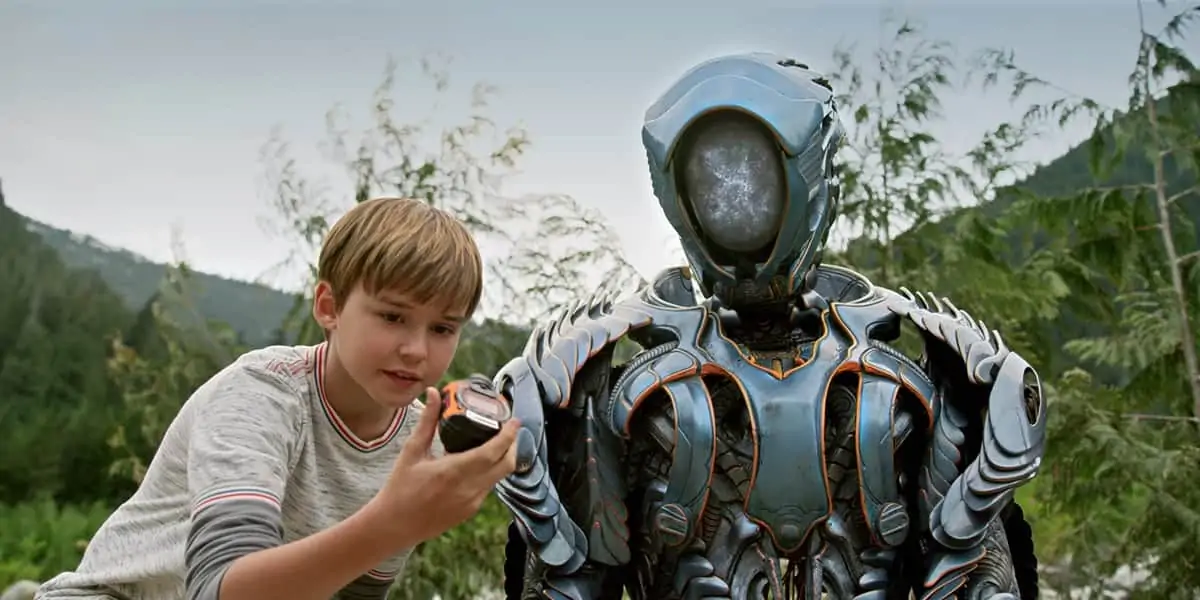

Indeed, there is scene in one episode in which a young member of the family has a close encounter with a creature, deliberately echoing an iconic shot of Elliot befriending E.T.

“We are all big fans of sci-fi – Neil, Zack and I – but we were keen to do something that wasn’t a brash, glossy superhero show. We wanted to build a world that was completely ours, but there are some definite references in there.”

The biggest thematic reference though was Jurassic Park/Jurassic World. “We know we are making a family show but it’s one grounded in a reality,” says McCurdy. “Because of the freedom Netflix gives you we knew we had the support to make this more a theatrical than a TV visual experience.”

They were wary too of comparisons with Netflix’s Stranger Things, wanting to differentiate their story by delivering a modern rather than ‘80s nostalgic look. The template here were Christopher Nolan’s films from The Prestige to Interstellar, which infuse high-concept with realism.

These sensibilities led to McCurdy’s choice of the Red Weapon with Helium 8K S35 sensor. “I’ve been a believer in Red for some years and applaud the way they try to develop new technologies to suit new ways of filming,” he explains. “We tested the Helium extensively and it was quickly apparent that there was nothing else out there like this in terms of its modern look.”

McCurdy paired the Red Weapon with a set of Leica Summilux-C Primes. “These offer a very sharp, European sort of feel if you draw it down a few stops, and a softer, American movie feel if you shoot a little more wide open,” he describes. “I wanted the softness to depict the family, but the extra sharpness and extra depth-of-field for visual effects to play around with.”

With a third to half the total budget being spent on visual effects, McCurdy wanted his shots to be big. “We don’t need to be spending money on a greenscreen comp outside of a window. If a shot needs VFX then let’s make it a big shot. Let’s make sure they are getting money from the set. So, we framed for family/group shots rather than close-ups. For me, this takes on a much more cinematic feel because you are not just cutting heads together but cutting from group shots against amazing locations and sets.”

The theatrical aesthetic also determined the use of two cameras (A-B) - and primary use of dollies and tracks with very little Steadicam.

“Although we deployed two Weapons, we shot the show as a single-camera drama. We used very little handheld or Steadicam and instead went back to basics. We didn’t want the new gimmicks like fancy 360-degree shoots. I felt we needed to be intimate with the family and their drama, and we were there to photograph that.”

"We know we are making a family show but it’s one grounded in a reality. Because of the freedom Netflix gives you we knew we had the support to make this more a theatrical than a TV visual experience."

- Sam McCurdy BSC

Shot at The Bridge studio in Vancouver, a good third of the series used locations in British Columbia. “We travelled beyond Whistler and Blackcomb to mountain ranges covered in pristine snow. Just physically taking all the equipment up there was a big deal. The locations are remarkable and a big part of the show’s aesthetic.

“Even though we knew the plates would be augmented by VFX – and they could have chosen to design everything in a laptop – we all wanted to keep as much reality flowing through the piece as we could,” McCurdy notes.

The planet on which the family Robinson crash land houses several ‘eco-structures’ ranging from barren, snowy mountains to glacial landscapes and a rainforest with 30-foot diameter giant redwoods.

“You are kind of blown away by the sheer scale of this wilderness and that’s entirely what we wanted to capture,” he says. “The Helium was phenomenal in natural light. It has a softness and a curve that coped with the extremes of big skies and snow as well as contrasts of massive tree lines and being deep in forested areas. We pushed it as far as we could, and it upheld for creative reasons and for VFX. The depth of exposure and latitude gained by the sensor meant it was the obvious choice.”

With a 4K deliverable requirement, McCurdy shot 7K compressed 7:1. McCurdy, along with production designer Ross Dempster and gaffer Todd Lapp, devised a lighting system for the spacecraft, crew quarters, mobile vehicles and ‘garage’ to operate in a range of different scenarios. The fixtures were routed back to a console for McCurdy’s control, for example, switching the lights to ‘emergency’ mode or having individual lights illuminate parts of the ship as a crew member walks through them.

The inspiration for part of the design was the smart lighting effects found in modern office buildings, which switch off after a certain time, or switch on automatically when they detect movement. “Each of the fixtures had a daylight tungsten LED and an RGB LED system in it so we could mix any combination of colours and run sequences at a flick of a switch. This gave us incredible 360-degree freedom to move the camera where we wanted.”

He adds, “It was an incredible experience technically and creatively because we weren’t tied to the key lights. I don’t think we ever had need in any episode to bring a key light onto the set.”

Preferring to mix the camera “for the moment” rather than use a LUT, McCurdy set daily parameters with the on-set colourist. “The colour was then kept through the offline but inevitably when it came to DI, with so many VFX shots needing to go in, some things changed. A scene that was maybe scripted as dawn or dusk ended up as day or night.”

In what is now becoming commonplace for high-end drama, the entire show was given a HDR pass, as well as an SDR master. “Having done a few HDR shows, I was keen to split the two. You can’t just let one copy across to another. You need to start from scratch and Legendary were very understanding with this, giving us a week for the HDR and 4-5 days for the SDR colour correction [in the pilot] with time reducing a little per episode.

“I was very proud when I saw the first cut of the pilot. It felt like a movie.”