SWEET SUCCESS

Wonka‘s cinematography shifted unexpectedly from Seamus McGarvey ASC BSC ISC to Chung-hoon Chung ASC, marking a pivotal turning point and making the South Korean an accidental hero in shaping the film’s vision.

The latest motion picture inspired by Roald Dahl’s beloved Charlie and the Chocolate Factory takes a bold departure from what were otherwise adaptations of the 1964 classic children’s novel. Delving deeply into Willy Wonka’s mysterious past, it intricately explores his eccentric character and origins while crafting a unique narrative around the chocolatier’s beginnings. Notably, the film presents an original storyline, distinct from Dahl’s ‘pure imagination’, inventing entirely new circumstances for the top-hat wearing Wonka’s journey while drawing inspiration from, yet not duplicating, the late author’s work. Additionally, it marks the first time Charlie Bucket isn’t featured on screen.

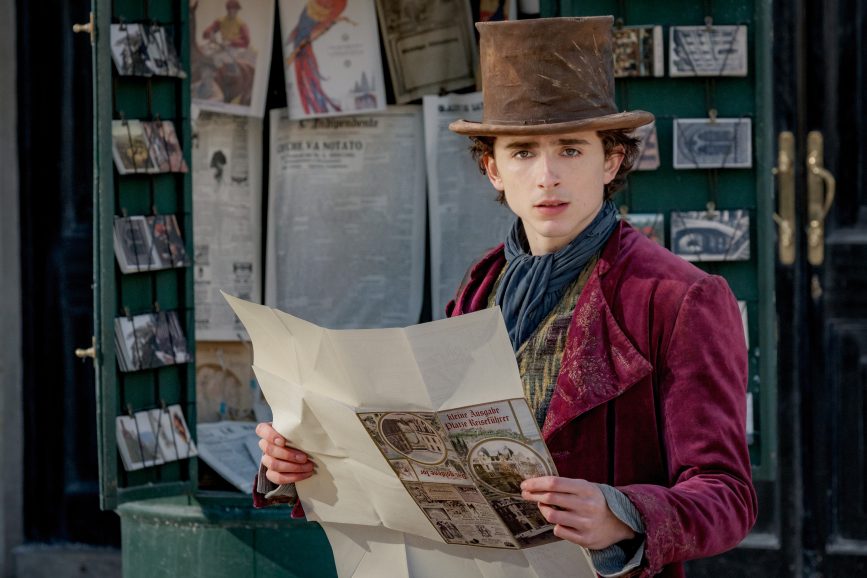

Co-produced by Village Roadshow Pictures, The Roald Dahl Story Company, Heyday Films, and Domain Entertainment, Wonka is a musical fantasy film directed and co-written by Paul King (known for Paddington and Paddington 2). Chronicling the protagonist’s early quest for fortune, Timothée Chalamet’s character arrives in an unspecified European city – one that appears as a picturesque blend resembling London, Paris, Geneva, and possibly Brussels – to set up a chocolate shop. In reality, the film captures scenic English locales, such as Oxford, Bath, Lyme Regis, London, St. Albans, and Warner Bros. Studios Leavesden. Filming at the latter began in the autumn of 2021 and continued for 21 weeks, utilising over 50 sets built across three sound stages. Facing challenges, forming an unlikely group, and overcoming adversities, Wonka realises his dream with newfound friends. The ensemble cast also includes Rowan Atkinson and Olivia Colman, with Hugh Grant portraying an Oompa Loompa.

What’s more, another intriguing facet of this film lies beyond the camera lens. Initially, Seamus McGarvey ASC BSC ISC (Cyrano, The Greatest Showman) was scheduled to lens the film, yet instead of stepping into the role, he graciously and rather surprisingly passed his golden ticket to a friend.

“He called to say ‘can you replace me?’” says Chung-hoon Chung ASC, the South Korean filmmaker and cinematographer whose credits include Last Night in Soho and Obi-Wan Kenobi.

When he joined the production, the format and technical aspect of the film were already in place. However, Chung retained his specific vision, which he presented to director Paul King. The objective was to distinguish Wonka from Gene Wilder’s memorable portrayal in Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory (1971), directed by Mel Stuart, and Tim Burton’s newer version, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory (2005), featuring Johnny Depp, while maintaining a harmonious connection with both films.

The divergent cinematic tones between the 1971 and 2005 productions would have made it tempting – for some – to take creative risks filming Wonka. Exploring the chocolatier’s youth opens doors to fresh narratives, inspiring a bold approach that embraces innovation. The opposite was true in Chung’s case.

“To be brutally honest, there were no innovative techniques introduced,” Chung explains. “The moment I received the offer for this film, I knew how I wanted to shoot it and that it shouldn’t feature special, innovative, or flamboyant camera movements. My aim in this film was differentiation. With numerous characters, I used anamorphic or spherical elements – depth, curvature, and distortions – to distinguish each character.”

Chung worked with an ARRI Alexa LF and employed Apollo’s Xelmus Anamorphic as well as Cooke Anamorphic lenses to achieve this vision.

“I aimed for a classic approach,” he continues. “It’s similar to Gene Wilder’s film in its analogue and classic essence and we wanted a different chocolate factory, but similar to the one in the Wilder film – that’s what we achieved, if I executed it correctly. We shared the idea of an analogue feel, despite numerous fantasy elements. We wanted to make it truer, real and as in-camera as possible. People often automatically think of Tim Burton’s Wonka, which I admire, but that film leans more towards digitisation, a look we aimed to avoid.”

Cue the music

The film artfully incorporates the cherished scores, iconic melodies, and songs from the 1971 version, aligning with its nostalgic essence and blending the past and present of cinema. This integration posed multifaceted challenges for Chung as he navigated Wonka’s musical essence, merging music, choreography, and aesthetics.

“Approximately 90% of the film relied on LED lights, all meticulously synchronised using a dimmer board,” he elaborates. “Upon reviewing rehearsals, I swiftly adjusted colours and cues, ready to make on-the-spot changes as needed. I developed multiple backup plans based on actors’ performances and dance sequences. My approach doesn’t hinge on actors hitting specific marks for lighting; I anticipate and adapt in real-time. Given the nature of a musical with intricate choreography, actors occasionally miss their marks, and it’s my role to accommodate them through lighting adjustments. This required meticulous planning from our gaffer, Lee Walters, to execute seamlessly, which he did exceptionally. The remaining 10% of the film utilised tungsten, par cans, and HMIs – such as in the wash house scenes.”

Darkness and light

A pivotal film moment shines during the grand opening of Wonka’s store. Unfortunately, proceedings deviate unexpectedly from the owner’s plan, stirring chaos and dramatic challenges for the man in the top hat. The particular scene also posed challenges for the camera crew, as Chung attests.

“That was probably the most challenging one,” he recalls. “It starts in a dim and dark place and as the customers come in, the store gets brighter and colourful. But after the customers start consuming the poisoned chocolates the store gets ruined and we had to show that with lighting. Then there’s the beautiful cherry blossom tree, through which the sunlight comes and hits the customers coming into the store. The problem was there were so many branches and leaves, it meant planting a mixture of Par Cans was difficult because the tree blocked a lot of light. I told Lee what I wanted and he made it happen, with a mixture of 5K and 10K lights.”

Chung doesn’t have a favourite scene, instead expressing his affection for all of them. Yet, if pressed to select, he’d opt for the one above. Not solely due to its difficulty, but for its captivating visuals. “Right before Wonka unveils the shop, emerging from the dark, we catch a profile shot with a striking edge line – that revealing moment – and that particular shot resonates with me,” he shares.

VFX treats

The film radiates authenticity: unlike in past adaptations, every confection in Wonka is edible. A dedicated chocolatier was brought onto the set to ensure the genuineness of the chocolates featured in the movie, highlighting the significance of crafting genuine treats for the film. That said, Framestore’s VFX team helped bring King’s vision of the magical world of Wonka to life across 922 shots. VFX supervisor, Graham Page, alongside Framestore’s pre- production services, art department, and VFX crews in London, Montréal and Mumbai gave life to delightful creatures, sumptuous environments, 300,000 gallons of digital chocolate and a fully-realised digital actor for the Oompa Loompa.

Chung worked closely with Graham Page, but the cinematographer points out that Wonka only deployed VFX very lightly. “Whilst there are a number of VFX shots, they are classic ones,” Chung continues. “For example, when the characters are flying in the air, it was all wires. It would have been a lot easier to use VFX, but the idea was to stick with the classic method. Out of all the VFX-heavy films I’ve worked on, this was probably the easiest.”

Page adds that VFX on Wonka “covered the full gamut of challenges”, dealing with digital characters, creatures, environments, crowds and an embarrassment of that rich, velvety treat derived from cocoa beans.

“We were always keen for our work to sit in the same world as the live action material,” he says. “Collaboration with Chung-hoon was great – he’s got an incredible ability to come up with ideas quickly and is fantastically fun to be around. It was such a joy to see his approach to lighting and we tried to carry through many of his techniques into post in particular while working on the Oompa Loompa where Hugh’s digital closeups needed to complement Timothée’s.”

Chung also feels compelled “to express gratitude and a kind of apology” to McGarvey for this incredible opportunity and his trust in assigning such a significant project. “The absence of any prep made each day on set a commitment to not disappoint Seamus McGarvey. He paved my way here and that’s what drove me to excel.”

Marzano Films was on aerial cinematography duty for the film, using their Mini Eclipse helicopter system and the Freefly Alta X with a Ronin 2. Innovation was at the heart of their work; one key example being a bonkers scene where a giraffe runs down the length of the knave in St Paul’s Cathedral. “The authorities understandably refused to allow us to fly our drone inside the cathedral and conventional crane arms weren’t light and mobile enough for the pace required,” John Marzano explains. “Working with the brilliant grip department we created a rig that put a lightweight stabilised camera mount at the height of a giraffe’s head. This was mounted on a simple wheeled trolley which was then pushed down the knave and the running speed of a giraffe.”

Another challenge for the team was the plates for Wonka’s balloon flight. Marzano remembers: “It was very cold night shoot and with the three-camera array we were carrying the maximum amount of weigh under the drone. Consequentially, the batteries discharged very quickly making for short flight times. We had to be spot on with every take to maximise the success of the shoot.”

Wonka worldwide

Ray Gillon, whose company G-Minor did dubbing on the film, explains how one of the many challenges in recreating a foreign dubbed version is trying to maintain the width and breadth of social landscape. “So, the range from the raucous (but brilliant) Mrs. Scrubit and her lummox of a partner (equally brilliant) Mr. Bleacher to the three chocolatiers, who were excessively elegantly spoken British English, not forgetting the crisp wit and articulation of one Hugh Grant, who delivers deliciously dryly, required detailed character explanation,” he says. “Consider that newer markets lacked exposure to the societal tiers we refer to for many years. We spent months voice testing main characters around the world to ensure that dialogue and singing abilities were up to par.” He adds that 37 dubbed versions were created for a near day-and-date worldwide release, reflecting meticulous efforts to maintain cultural nuances across different markets.

“I am now well into my 40th year of working in foreign language dubbing and seeing it come together well gives me and colleagues a healthy kick,” Gillon continues. “Many thanks to Ian Duncan and Russell Heeks’ team at Deluxe, Perivale for their talents and perseverance in the amazing mixing facilities of eight Dolby Atmos rooms.”

Gillon predicts box office success, praising King and producer David Heyman, anticipating future collaborations between them. “My hat goes off to them for many things not in my area of remit but the casting was sublime,” he continues. “By eschewing formula and choosing really good solidly developed characters, King avoided many of the traps that lead you along a path to saccharine performance and delivery.”

You’ve heard from the filmmakers. For everyone else, an all-round scrumdiddlyumptious movie awaits.