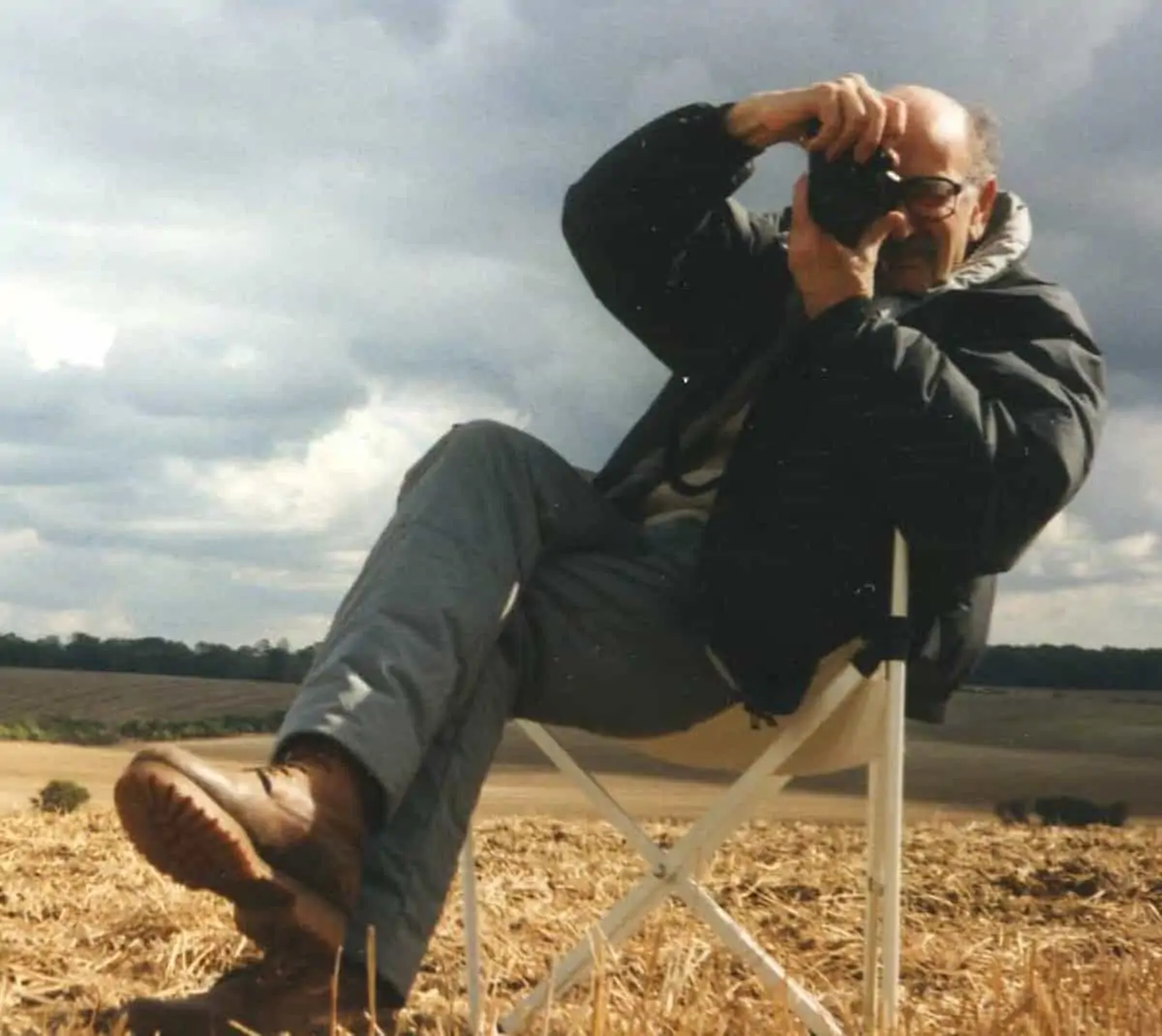

Although born in Vienna, the photographer and cinematographer Wolfgang Suschitzky, who has died aged 104, forged his career in the UK where, as a Jew and a socialist, he took refuge in the 1930s.

Suschitzky’s father, Wilhelm, and mother, Adele (nee Bauer), were secular Jews who owned a radical bookshop in Vienna. Wilhelm, a noted free-thinker, killed himself during the rise of Nazism. Wolfgang’s elder sister, Edith (later Tudor-Hart), was also a photographer, and a great influence on her brother.

Suschitzky left Vienna, and the Austrofascist regime that seized power in 1934, for Amsterdam, where he met and married Puck Youte, with whom he opened a photography studio. By 1935 the marriage was ailing and he left for London. There, he met Paul Rotha (film director and documentarian) and they began to work together. Suschitzky was committed to photographing his adopted homeland and to helping others escape from his former one, including his two brothers who, having been held at Dachau, were eventually released, only to be interned on the Isle of Man.

Despite graduating in photography from the Höhere Graphische Bundes-Lehr- und Versuchsanstalt (School of Design and Graphic Arts) in Vienna, Suschitzky’s first passion was zoology, and he found lifelong pleasure in photographing animals. His animal portraits have a particularly Bauhaus imprint, his zebras a study in geometry.

In 1940 he held his first exhibition – of animal pictures – in London and published his first book, the “how to” guide Photographing Children, which was followed by Photographing Animals a year later. He was characteristically modest: “Any competent photographer can take good animal pictures; there is no particular technical knowledge required … I have the greatest respect for the nature photographer and for those who take pictures of animals for scientific records.”

His childhood ambition had been to become a zoologist and in 1956 he was delighted to supply the photographs for the book The Kingdom of the Beasts by Julian Huxley, whose scientific views closely corresponded to his own.

He preferred to photograph in natural light, if possible out of doors, and the Photography Year Books printed annually in the 1950s and 60s frequently included his images of children engrossed in building sandcastles and skiing down mountain slopes, while the World Exhibition of Photography used others in the shows What Is Man? (1964) and Woman (1968).

His early cinematic work – in collaboration with the director Paul Rotha – was in a documentary style similar to that of his stills, with titles such as Children of the City (1944 Directed and written by Budge Cooper), a dramatised study of deprived children in Dundee, the BAFTA-winning The World Is Rich (1948 Directed by Paul Rotha), a hard-hitting documentary that looked at food distribution following the second world war, and No Resting Place (1951 Directed by Paul Rotha), a dramatic feature about an Irish traveller who kills a game keeper by mistake centering on rural life in Ireland and was among the first British feature films shot entirely on location. He also worked on Jack Clayton’s Oscar-winning short The Bespoke Overcoat (1955 Won an Oscar for best short subject).

Suschitzky was the cinematographer for the highly successful Get Carter (1971 Directed by Mike Hodges), shot on location in north-east England, starring Michael Caine and as a freelance cameraman became increasingly heterogeneous, with films as diverse as Ulysses (1967 Directed by Joseph Strick) for which he received a BAFTA Nomination, Ring of Bright Water (1969 Directed by Jack Couffer) and Entertaining Mr Sloane (1970 Directed by Douglas Hickox); and those on the artists Poussin (1968) and Claude Lorrain (1970). He was always realistic that it was the film work that paid the bills to support a growing family – he had three children, born to his second wife, Ilona (nee Donat).

By the 1980s, Suschitzky was also working in television commercials and was the cinematographer for the children’s series Worzel Gummidge (1980-81 Directed by James Hill and David Pick) for which he was nominated for BAFTA TV award. In the same decade he began to receive somewhat belated recognition for his still photography, in the Art in Exile exhibition in the UK (a touring show that originated in Berlin) and exhibitions in London at the Photographers’ Gallery, Camden Arts Centre and Zelda Cheatle Gallery. The work on display at the last of these presented images of both his abandoned and his acquired homelands, as seen in Suschitzky’s book Charing Cross Road in the 1930s (1989).

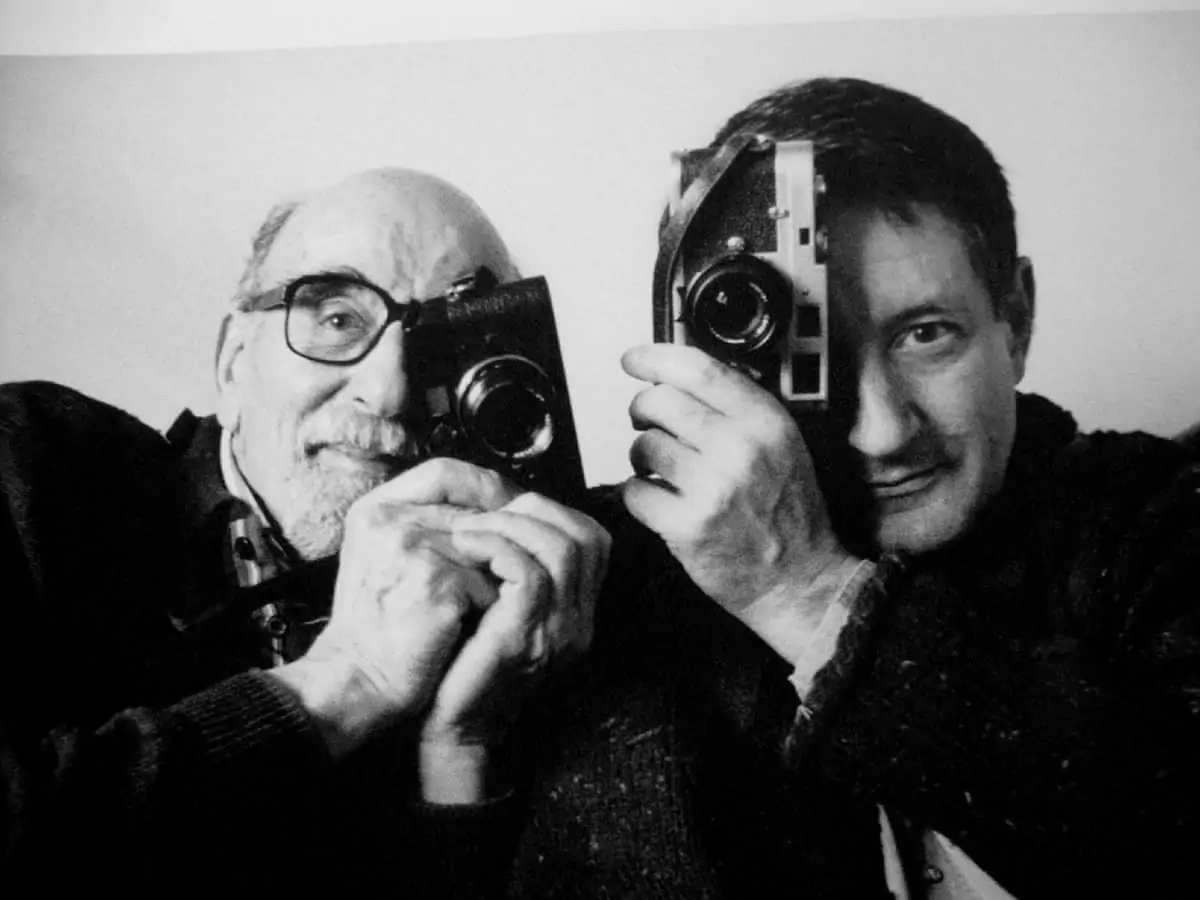

More recent publications include the retrospective Wolf Suschitzky Photos (2006, introduced by the Magnum photographer Erich Lessing), and Wolf Suschitzky Films (with a tribute by the Get Carter director, Mike Hodges), in 2010.

Suschitzky’s still photography has enjoyed something of a renaissance in recent times with his inclusion in a number of group shows including Another London: International Photographers Capture City Life 1930-80 at Tate Britain in 2012. On his centenary, in he received a BAFTA special award for his cinematography. Seven Decades of Photography (for which I wrote an introduction) appeared in 2014. In the same year he was granted an honorary doctorate at the University of Brighton.

Earlier in 2016 he shared a major exhibition with Dorothy Bohm and Neil Libbert, fellow photographers of his heritage and generation, at the Ben Uri Gallery in north London. Called Unseen, it and the accompanying book drew further on “overlooked” images of London, Paris and New York by the three photographers, who all attended the launch.

Suschitzky believed that great photography is “a combination of the right choice of detail, the elimination of all that is inessential and the right moment that makes the picture”. He demystified his technique still further, by adding: “I was always quite content to be a good craftsman.”

Suschitzky’s marriage to Ilona ended in divorce. He is survived by his partner, Heather, his children, cinematographer Peter, Julia and Misha, his grandchildren and his great-grandchildren.