Hungry like the Wolf

Clapperboard / Wolfgang Suschitzky

Hungry like the Wolf

Clapperboard / Wolfgang Suschitzky

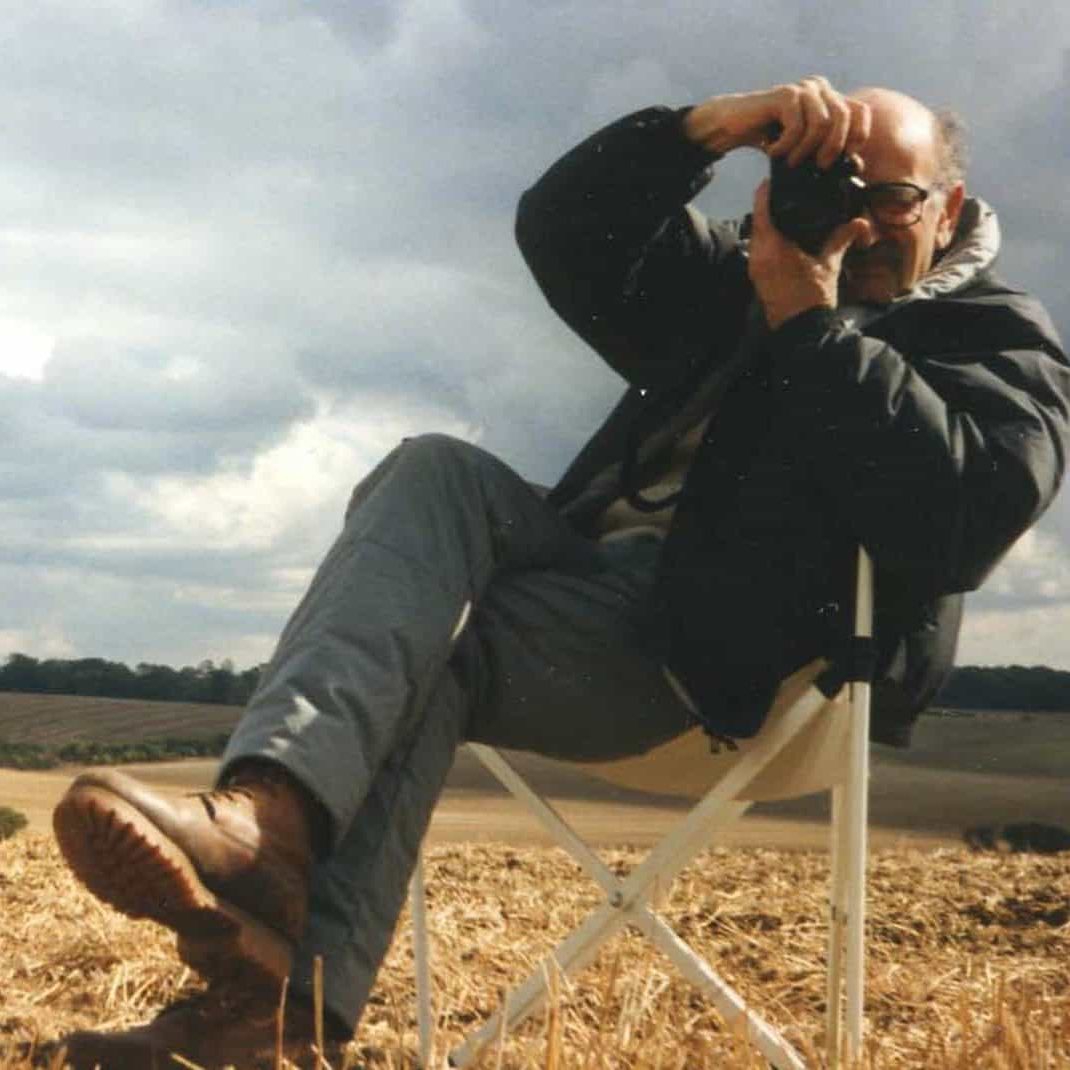

Legendary photographer and cinematographer Wolfgang Suschitzky, known as Wolf or Su, was born in Vienna in August 1912. His father Wilhelm and his uncle Philipp opened the first socialist bookshop in Vienna. Later, the pair set up the publishing house Anzengruber, specialising in social criticism and pacifist themes. Suschitzky trained as a photographer at the Hohere Graphische Bundes – Lehr und Versuchsanstalt in Vienna for three years.

From an early age Suschitzky was taken to the cinema. He is quoted as saying, “I wasn’t fourteen yet, but an older cousin of mine smuggled me in to see the 1926 horror film The Phantom Of The Opera.”

In 1934 after studying photography with Rudolph Koppitz he left Vienna and went to Amsterdam, photographing the city’s poor Jewish areas. He came to England in 1935 where he established himself with photo reportages for magazines including Illustrated Picture Post and Animal & Zoo magazine. He said he used Rolleiflex and several single lens reflex cameras before settling on a top of the range Hasselblad.

In 1937-1938 he took photographs for the Charing Cross Road series. Those photographs have become classics of modern black and white photography. Suschitzky says it was those pictures that led him to work with Paul Rotha, one of the people involved in the documentary movement. Rotha was a producer with Strand Film, based in London’s Oxford Street, later moving to Soho. Suschitzky said: “I was just lucky to get an introduction to Paul Rotha. It was the tail end of the documentary movement. I thought the movement was very good because they wanted to make films useful to society, and as a socialist that appealed to me.

“We usually shot documentaries silent, shooting with clockwork Newman Sinclair cameras. They had to be wound for each shot because they didn’t pull more than a hundred feet of film.”

He first worked for Rotha as an unpaid assistant cameraman, shooting films at the zoo with a young director/ cameraman called Paul Burnford

After Strand, Rotha ran Paul Rotha Productions until 1944. Rotha then became involved in The Documentary Technicians Alliance (DATA). Suschitzky was among the co-founders. It was the first film cooperative in Britain. Suschitzky said: “I belonged to Paul Rotha Productions. Later we formed the first cooperative film unit in Britain and I worked for them for twelve years. They gave me time off if somebody else offered me an interesting job. During that time I went to NBC New York to shoot the Wisdom series.”

Suschitzky shot his first feature No Resting Place in 1951, directed by Paul Rotha. “We shot it like a documentary and it was photographed entirely on location, which was rather rare in those days because most feature films were made in the studio," he said. “In features I went straight in as a cameraman, DP, by-passing the focus puller and operator stages. I called myself a cameraman; I always thought director of photography was rather pompous.”

Asked if he had a favourite film he had shot, he replied, “It’s difficult to say, there were several I enjoyed very much. One of the first was The Bespoke Overcoat (1955). It was shot in a converted chapel on the Euston Road, London. Jack Clayton was the director. It was his first film as a director. He had produced, but never directed. Romulus gave him six thousand pounds to make a short film. It won an Oscar for best short film. It also won a BAFTA special award and a prize at the Venice Film Festival”

Suschitzky shot most of his films on location and Fuji and Eastmancolor were two of the stocks favoured. “I shot most of my films on location, but there were a few done in the studio, The Small World of Sammy Lee (1962) for instance. It was on Sammy Lee that Tony Newly said I don’t know how to light a star.”

Which films did he enjoy working on? “I liked very much working on Ulysses (1967), Get Carter (1971), which was shot entirely on location, Theatre of Blood (1973), which starred Vincent Price, The Bespoke Overcoat with Alfie Bass, Entertaining Mr Sloan (1969) and Ring of Bright Water (1969). Michael Caine was very professional in Get Carter. He was always there when he was needed and always knew his lines. He was very pleasant to work with. I quite often had lunch with him and the director Mike Hodges. Vincent Price was also very sociable. On the first day of the shoot he shook hands with everybody in the studio.”

"We usually shot documentaries silent, shooting with clockwork Newman Sinclair cameras. They had to be wound for each shot because they didn’t pull more than a hundred feet of film."

- Wolfgang Suschitzky

Ulysses, directed by Joseph Strick is regarded by some as an outstanding example of Suschitzky’s B&W cinematography. Asked if he preferred working in colour or black and white, he said: “I didn’t mind really. I never worked on the three-strip Technicolor camera. I began to work with colour when single colour film came out. It was almost easier to work in colour than in black and white. With monochrome you have to light much more carefully and get some modulation on the actors faces.”

When asked which was his most difficult film he commented: “Well, none of them were easy, every set up is a new problem, that makes our work so interesting. I was very lucky to have worked with decent people. Directors and producers always treated me well and I got on with my crew. I had some very good camera operators and focus pullers.”

Did he have a favourite camera? “I didn’t have a favourite, but the Panavision camera was very good to work with.”

As for what advice he would give to a budding cinematographer he replied, “I would advise a new cinematographer to spend a month or two in the cutting room. I regret that I never spent time in it, I never had the chance. I had to learn from directors how they analysed a scene.”

Suschitzky said that he didn’t usually stick to the same crew. He says he had been fortunate to have good crews and says that the operators and focus pullers contributed and helped him a lot.

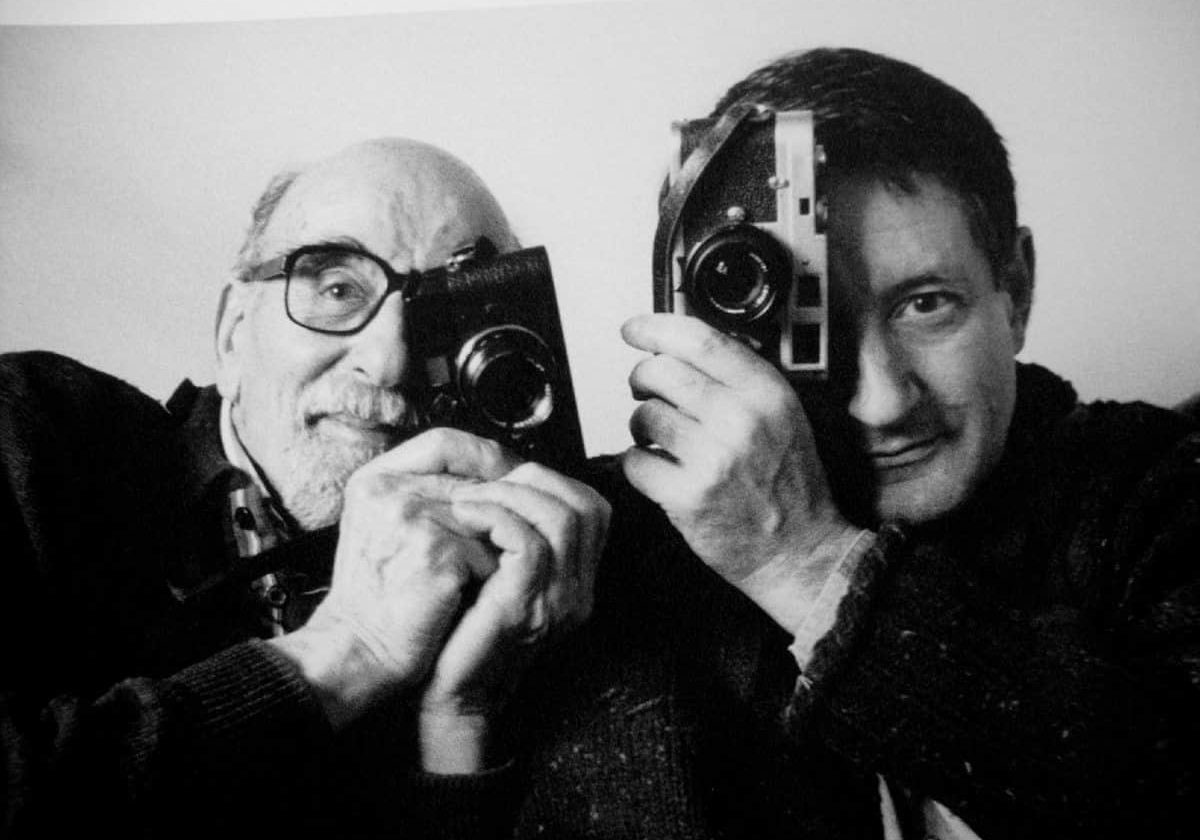

Suschitzky’s son Peter, and grandson Adam, have also become cinematographers. “Peter got an interest from watching me. For a short time he went to a film school in Paris. His first film was shot voluntarily for film historian Kevin Brownlow called It Happened Here, which was filmed on a shoestring. Peter is currently working with David Cronenberg on a film about Sigmund Freud called A Dangerous Method. He likes to do his own operating. My grandson Adam went to Beaconsfield film school.”

What does he think of cinematography today? “It is wonderful, you never see a badly photographed film. I haven’t seen one and I see quite a lot being a member of BAFTA.”

Talking about digital he said: “Digital is a tool, I am not against it. It all depends on the cameraman/woman and director and what they want to do with it. Any tool, even a pencil can create a work of art. If you have a tool that is more flexible and easier to work with, it should be used, but it is more important to have a good story and actors. There are a number of films that are resting their reputation on special effects.”

Apart from features, television and documentaries, which include a number of Mining Reviews from 1948-56, he shot a good many commercials. TV work included an early episode of The Invisible Man. He finally shot The Vanishing Costumes (1993), a video about customer service.