Johan C.M. Wolthuis, International 70mm Publishers, Arnhem, The Netherlands (www.70mmpublishers.nl), discusses the history and future of 65mm filming and 70mm prints.

We are all looking forward with great expectations to the delayed premiere in February 2022 of Kenneth Branagh’s latest 70mm film production Death on the Nile, based on Dame Agatha Christie’s 1937 novel. If you have seen the trailer of the film, complete with beautiful boat scenes on the river Nile, it looks like real 70mm! Sir Kenneth Branagh is a 70mm fan – he started with the Panavision 65mm cameras in 1995 for his version of Hamlet, which was released with 31 70mm prints. It was a pity the film was not a success.

In 2017 he decided to use the Panavision Super 70 cameras again, this time for his version of Agatha Christie’s Murder on the Orient Express. The 65mm cameras were kept in pristine condition for all those years in the London branch of Panavision.

The revival of 65/70mm film has received a boost with the opening of Kodak’s 65mm film processing facilities in 2016 in the UK. Murder on the Orient Express was the first production to use the new installation. FotoKem in Los Angeles has now produced 32 70mm prints for Death on the Nile and EYE Amsterdam and KINO Rotterdam have both made a reservation for a 70mm print!

Cinematographer Haris Zambarloukos BSC said, “Film has a palette like no other movie format. When Ken and I first started talking about Murder On The Orient Express, we both just knew it was the one to put our hearts and souls into making in 65mm. It’s a rare thing to be able to bring to life a great piece of literature and we want the audience to have a truly immersive and intimate experience. Agatha Christie’s work is one of the greatest revenge stories and it has to be immensely entertaining on the big screen. We want to make a film were you feel every stab wound, and we couldn’t think of a better way than to shoot it on 65mm film.”

David Barron, who was the producer of the 1996 production of Hamlet, said: “We shot on 65mm film because we see our Hamlet, as an epic film. An epic film demands an epic format. One which gives us absolute quality. One that gives nearly four times the picture information in each frame, relative to 35mm.” But the release was not the expected success they were hoping for!

Adrian Bull, managing director and co-founder of Cinelab London, commented, “65mm is the Holy Grail for cinematographers, so it is really exciting to see it returning to the UK as part of a more general film renaissance. Cinelab London’s 65mm service, in partnership with Kodak, will further cater to the needs of UK and European filmmakers who have specific requirements for the larger film format. Compared with 35mm, filming in 65mm allows directors to make much greater use of wide shots because of its enhanced definition and detail.

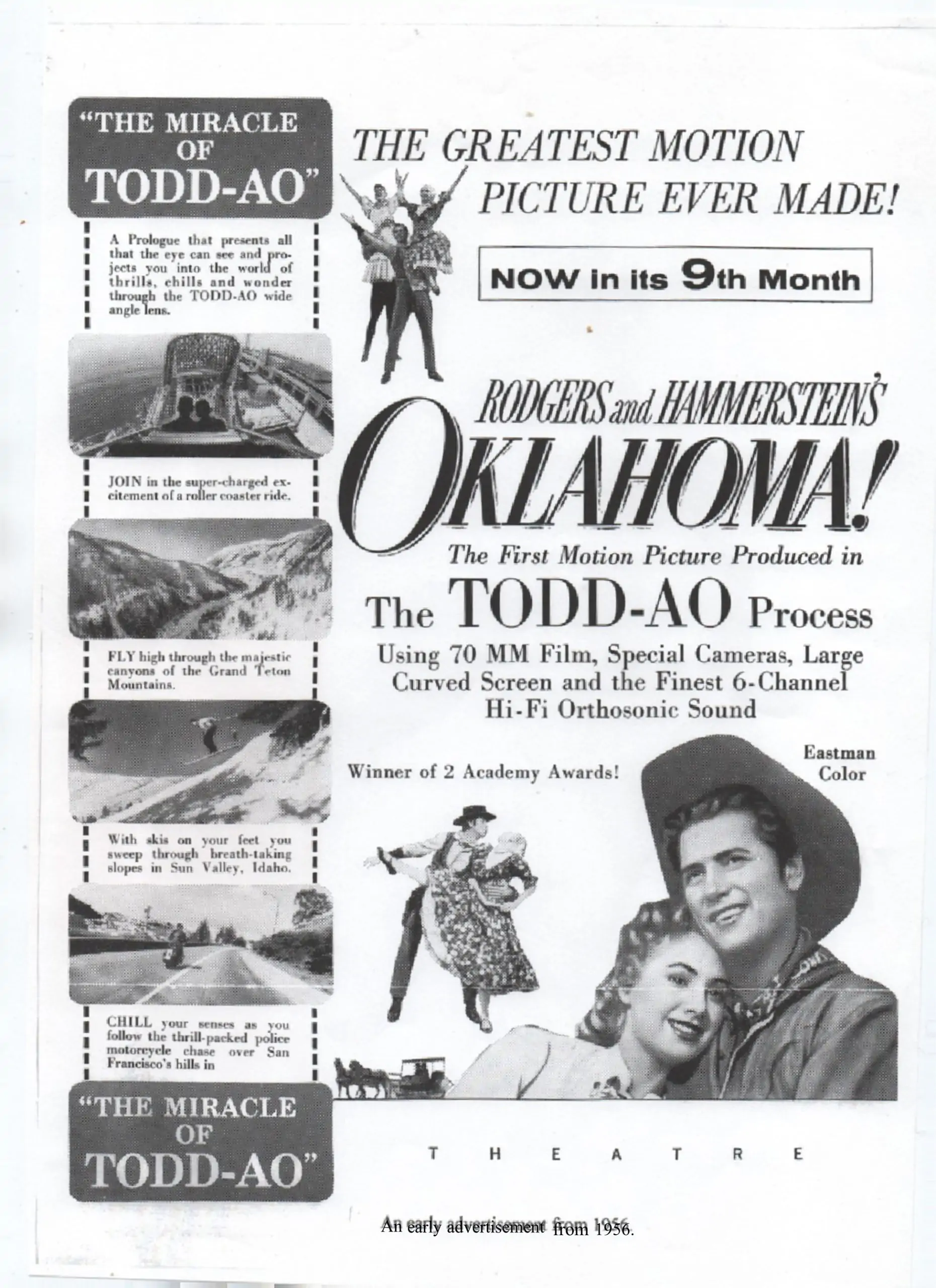

65mm celluloid film has a long and illustrious history and has been used for many masterpieces such as David Lean’s multi-Oscar winning Lawrence of Arabia (1962), for epics like Ben-Hur (1959) and Cleopatra (1963) and for famous musicals such as Oklahoma! (1955), My Fair Lady (1964), The Sound Of Music (1965), Hello Dolly (1970) and West Side Story (1961).

A little more 70mm history

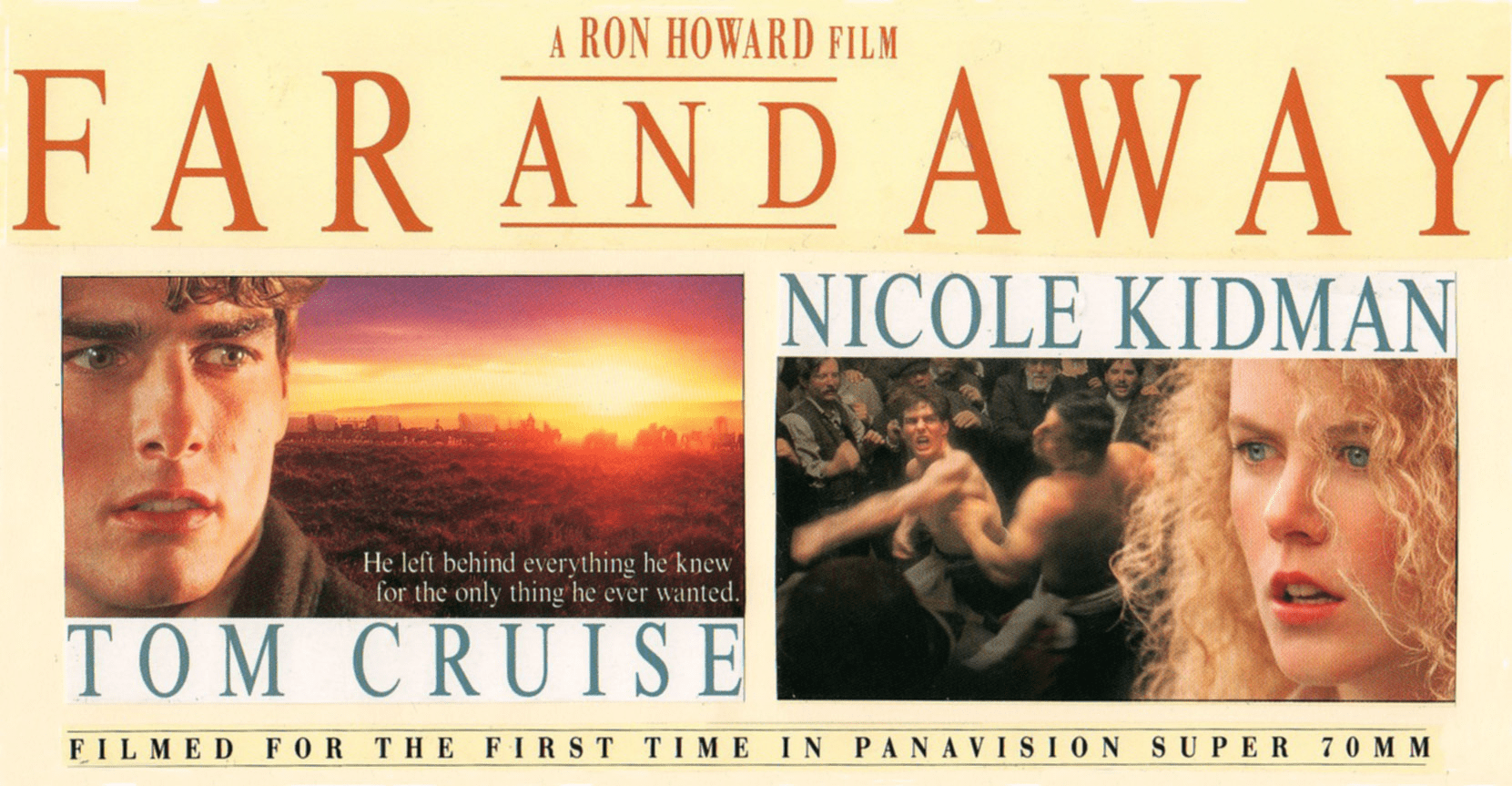

In May 1992, Variety wrote: “The Future of 65mm productions is fuzzy” – a story about the release of Far and Away (with Nicole Kidman and Tom Cruise). It was the first film shot with 65mm cameras since Disney’s TRON in 1982. For the release of Far and Away in May 1992, Universal had 1,500 35mm prints and and 163 70mm prints available for national release in the US. Producer Brian Grazer and director Ron Howard said that their movie was a test case for 65mm production. Michael Salomon, their director of photography added: “People do notice the difference: the definition, the clarity, the colour saturation – even if it’s on a subconcious level.”

Was the added cost of shooting in 65mm worth it? Grazer said that the decision to make Far and Away in 65mm has raised the budget by only $ 700 000 – an inconsiderable sum for an already high-cost film. (See “Digital & 65mm”, © 2010 International 70mm Publishers, The Netherlands).

But again the success here was also not what they had expected and 70mm was still not back in the front lines. In 1993 Bernardo Bertolucci and his DP Vittorio Storaro ASC AIC decided to use Arriflex 65mm cameras for parts of their Little Buddha production (with Keanu Reeves as Prince Siddhartha) which were shot in the Kingdom of Bhutan. The rest of the film was shot in 35mm anamorphic Technovision. A small number of 70mm prints was available for the release. The film was also not a success.

In 1996, Kenneth Branagh showed his love for 70mm by using new Panavision 65mm cameras for his four-hour production of Hamlet together with his DP Alex Thomson BSC. The process was renamed Panavision Super 70 because of the new lighter cameras. However Hamlet was also not a success, despite many 70mm screenings. In the meantime, producer Mark Magidson had used the Todd-AO 65mm cameras for his famous non-verbal production Baraka (1993), released with 70mm prints in 2010, followed by Samsara, filmed with Panavision 65mm cameras, but only released with DCP (Digital Computer Package).

Years of silence followed, until 2012, when Paul Thomas Anderson decided to shoot his production of The Master with 65mm Panavison cameras. A pity he didn’t use the full frame of the 65mm image! Anderson said: “The 1.85:1 aspect ratio sprang from how I saw things in my mind’s eye while I was writing”. But the release of some 70mm prints didn’t work well, as it didn’t have the impact of being 70mm.

Another fan of 70mm, Christopher Nolan, decided to use the IMAX 65mm camera for parts of his Interstellar movie in 2013. Cinemas had the choice to screen it with DCP or with 35mm film anamorphic (1:2.35), 70mm 5-perf (1:2.2) or IMAX 70mm (1:1.44). And in September 2015, Toronto Film Festival had the DCP premiere of Terence Davies Sunset Song, filmed with Arriflex 65mm cameras, but not released in 70mm. A missed chance!

In 2017, we saw the release of Christopher Nolan’s famous movie Dunkirk, shot with a combination of IMAX 65mm cameras and Panavision Super 65. They used the 65mm cameras for all of the close-ups, because close-ups are not that easy with IMAX cameras! The director of photography was Hoyte van Hoytema ASC FSF NSC – the well-known Dutch DP who lensed Nolan’s Interstellar and the latest 70mm movie from Nolan Tenet, which again used a combination of IMAX and 70mm cameras and released in July 2020.

Side by Side

In 2012, Keanu Reeves directed a documentary Side by Side (subtitled: Can Film Survive Our Digital Future) in which he collated nearly 70 interviews with film directors, cinematographers, writers, engineers, artists and producers, about their thoughts about digital filming. Among them were James Cameron, Anne V. Coates, David Fincher, Robert Rodriquez, David Lynch, Steven Soderbergh, Christopher Nolan, Vittorio Storaro, Vilmos Zsigmond and many others.

This featured questions about their experiences and feelings about working with film and digital — where are we now and what the future may bring. Martin Scorsese, who was also interviewed by Keanu, said he thinks that celluloid film will always be there.

According to the Side by Side website: “The documentary investigates the history, process and workflow of both digital and photochemical film creation. We show what artists and filmmakers have been able to accomplish with both film and digital and how their needs and innovations have helped push filmmaking in new directions. It is really a miracle that for almost one hundred years there was only one way to make a movie — with film. Movies were shot, edited and projected using photochemical film. But over the last two decades a digital process has emerged to challenge photochemical filmmaking. Side by Side takes an in-depth look at this revolution, what has been gained, what is lost, and what the future might bring.” The most surprising finding of the Side by Side documentary was that different producers said that they still would prefer the “old” way of using film instead of the digital possibilities, because the colours of the film are warmer.

However, in 2015 there was a lot of publicity surrounding Quentin Tarantino’s decision to shoot his production The Hateful Eight entirely with 65mm Panavision cameras. And not the normal Panavison 65, but the Ultra Panavision 70 (anamorphic) process that was used for the last time 50 years ago for Khartoum in 1966 and for Ben-Hur in 1959. And although the film had its premiere around Christmas 2015, a lot had been written before about Tarantino’s wish to release it the first two weeks only in 70mm and starting in January 2016 with the “normal” release. But even then with a choice of 35mm film or DCP!

Tarantino wanted to have 100 cinemas screen his movie in 70mm. And indeed: 96 cinemas in the US and four in Canada had 70mm prints on the first day of Christmas 2015. This was a complicated search for the 70mm projectors as well as for the special anamorphic 70mm lenses needed for the Ultra Panavision process! The Boston Light & Sound Company was involved in training staff and projectionists with the knowledge of running 70mm, as nearly every film projectionist in the world had been laid off and was working in other jobs (or not working, or was retired). Nowadays, some famous Philips (Norelco) DP 70s from the fifties, are still in use in the new EYE filmuseum in Amsterdam.

However, in Europe, not only in museums but also in cinemas there are still some 70mm machines waiting, covered with dust, for the things to come! Fortunately, 65/70mm film services are still alive and well at FotoKem in Burbank, CA, the world’s only complete 65/70mm film and digital post facility. They remain a solid resource for filmmakers interested in shooting their films in any format, from 16mm to 65mm, as well as on the latest digital cameras. They share with us the commitment to film origination and exhibition, and a particular love of 65mm capture and 70mm print exhibition. And the Kodak Factory in New York has been saved as the only facility still producing 65 and 70mm film. FotoKem so far has produced 120 70mm prints for The Hateful Eight. In July 2016 in France, Christopher Nolan shot his epic film Dunkirk, which was shot with a combination of IMAX 65mm and 65mm large format photography for maximum image quality and 70mm releases.

And the revival of real film has also received an additional boost with the fact that Cinelab UK, in partnership with Kodak, has installed a 65mm Photomec ECN2 film processor alongside their successful 35mm and 16mm services. The capacity to handle 65mm film processing in the UK complements the full range of large format and creative services available at Los Angeles-based post-production facility FotoKem film laboratory.

“I stumbled into the world of 65/70mm back in 1994. If you had told me at the time that I’d still be actively involved with the format in 2021, I would have never believed you. Which is to say, in answer to your question, I’ve learned over the years to never count out the power and allure of 65/70mm. I believe that there‘s a future for this format not because studios or filmmakers are lining up for our 70mm services, but because the format simply will not go away. I suppose it’s my version of “faith”! And it is, personally, my favorite way to view a film,” says Andrew Oran, GM, FotoKem.

In Amsterdam: 70mm was reborn

On January 7 2016, the 70mm screenings of The Hateful Eight started in the EYE Film museum in Amsterdam in their amphitheatre Cinema One with 315 seats. The first four weeks with three performances a day on the slightly curved screen which measures 14.25 m x 5.15 m. In seven weeks they 104 public screenings of the 70mm print, with a total of 28,000 visitors and an occupancy of 85 %. In four months, they sold more than 36,000 tickets untill the end of May. This is more than any other cinema in the world with a 70mm print of the Quentin Tarantino film. This 70mm film in EYE Amsterdam set the world record for the 70mm screenings of The Hateful Eight and ended as the most successful 70mm movie of this decade in EYE. They had enlarged the screen sideways especially for the movie.

A new light-weight handheld Magellan 65mm camera

In 2018, Logmar Camera Solutions from Denmark launched an new all-purpose handheld 65mm camera. The Magellan 65mm camera had been presented to the public at the Cine Gear Expo in Los Angeles in May 2018. The 65mm camera is the latest addition to long line of 65mm cameras to serve the motion picture industry. Todd-AO, Super Panavision 70, CINERAMA and IMAX are all examples of well known camera systems which have been used to photograph unforgettable musicals and epics like The Sound of Music, 2OO1: A Space Odyssey and How the West Was Won, and recent blockbusters like The Hateful Eight and Dunkirk. Remarkable films which have all been photographed on 65mm film.

The Magellan is a fully electronic, handheld and ultra-light all-purpose camera which will take large format 65mm photography to a new level. The possibilities with the Magellan are only limited to the imagination of the director of photography. This 65mm camera was designed and manufactured completely from the ground up by Logmar Camera Solutions, made in Denmark by camera engineer Tommy Madsen, CEO Logmar Camera Solutions – the lightest And most compact 65mm camera, weighing less than 12kg (26lbs).

Let us hope and emphasise that all cinema directors with 70mm facilities, their projection supervisors and other staff members will do their utmost to handle new 70mm prints with the highest possible care to prevent any damage of these new unique 70mm prints with Datasat (DTS) time code, so we will be able to watch these for a long time without any scratches. Not only in the United States, but also in Europe there is still a lot of interest in 70mm film, regarding the many yearly 70mm Festivals in Bradford in the UK, Karlsruhe in Germany, Denmark and Krnov in the Czech Republic.

Let us hope that Kenneth Branagh’s Death on the Nile will not be the last analogue 70mm and hope that 70mm stays with us for many years to come.

–

This article was written by Johan C.M. Wolthuis, International 70mm Publishers, Arnhem, The Netherlands (www.70mmpublishers.nl)

WIDESCREEN HISTORY

Johan Wolthuis is the author of Widescreen History. For more information and to buy a copy of the book please click here.

Book review by Jim Slater, former managing editor Cinema Technology UK.

“l enjoyed reading a publication from Johan Wolthuis of International 70mm Publishers in The Netherlands, as will anyone with an interest in widescreen and 70mm movies in their various incarnations. ‘Widescreen History’ is an A4 ‘landscape’ format softback of 62 pages, packed with text and pictures, many of them in colour. The chapters, written by Johan and a selection of widescreen industry ‘gurus’, include a history of widescreen cinema, a summary of the many widescreen processes and a detailed look at the sound and colour systems that have gone along with them.

Articles on Cinerama, Cinemiracle and Kinopanorama show how these led the way to CinemaScope and its ’55’ variant, and there are fascinating essays on Vistavision, Technirama, Super Technirama, Cinéorama, Circarama, and Circlorama. The history continues with pages on Grandeur 70, Todd-AO, MGM Camera 65 and Super and Ultra Panavision. IMAX and Omnimax complete the story and bring it up to date.

One of the strengths of the book is that it includes information on some of the cameras and of the projectors used with the different widescreen systems, including the remarkable Oscar-winning Philips DP7O. There are lots of pictures of film posters and advertisements in both colour and black and white, from the decades when 70mm thrived, making it a useful historical collection of memorabilia. lt is a very personal book in many ways, with lots of instances where Johan’s life-long love of 70mm shines through in his stories. There is an interesting piece about David Lean and his 70mm work, entitled ‘Master of Epics’ and other pieces come right up to date with the authors bemoaning the recent loss of projectionists and their traditional skills. There is even some information about a boothless cinema! This is unashamedly a book for enthusiasts, written by enthusiasts, and l am certain that many readers will want to buy a copy.”