Wait and see!

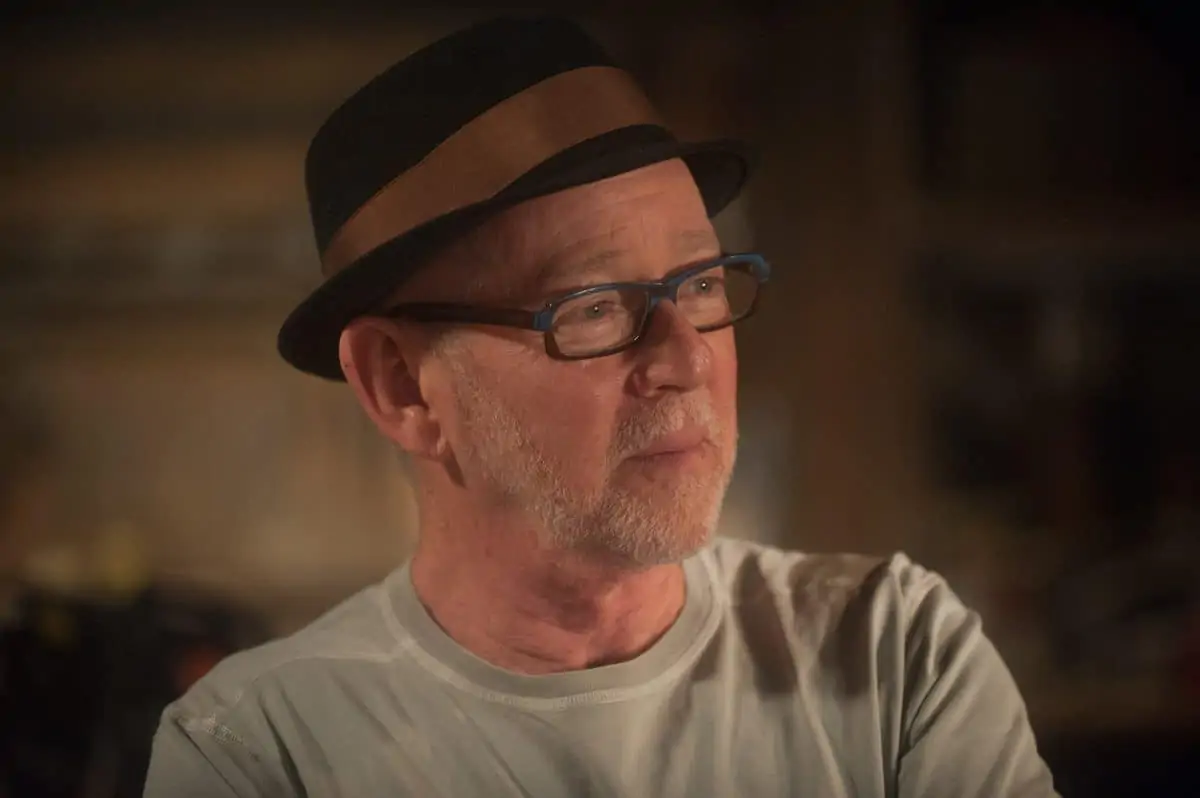

Letter From America / Steven Poster ASC

Wait and see!

Letter From America / Steven Poster ASC

Steven Poster ASC, national president, International Cinematographers Guild, IATSE Local 600, recounts how patience can be its own reward when it comes to maintaining artistic intent.

Learning the virtue of patience is not an easy thing. But patience can often bring life’s most desired rewards. More than 20 years ago, a small group of filmmakers, myself included, began talking about the transition from film to digital cinematography; we expressed great concern that the display of our work would not be accurately represented, particularly on television, which we knew was the way most people would see our films. This group included Rob Hummel ASC, who began his career at Technicolor and later worked with Douglas Trumbull when Showscan was being developed, and then many other studios over the years. One of the most important ideas that originated within our group was that there was enough room in digital recording to include what we called “a header descriptor” and what today would be described as “metadata,” that could adjust the TV for a nominally better picture than what is normally watched at home.

Why was a self-adjusting television so important? Well, I can remember going to my parents’ house in Chicago and always wondering why they sat there and watched purple TV! Usually after 15 minutes of trying to adjust the TV and my father yelling, “Stop! I just want to watch the baseball game,” I would realize there were only so many houses that we as filmmakers could go to and adjust television displays.

By way of some context: there’s a week each winter called the Hollywood Professional Association’s (HPA) Technology Retreat, where some of the deepest tech-heads in the industry go to the desert to talk about such obtuse subjects as parametric appearance compensation, blockchain technology, and black-level visibility as a function of ambient illumination (No joke!). The ICG started attending this event eight years ago, and when we showed up for the first time, people asked, “Why are you cinematographers here?” Then, after a number of years of contributing to the retreat, we were asked to make our own technological presentations. This past February, we put together a panel that included: Rob Hummel, now president of Group 47; Kelly Mendelsohn, representing the Producers Guild Of America; Bill Mandel, representing Samsung Research of America/VP of industry relations; Michael Chambliss, ICG technologist; Dan Rosen, formerly from Kodak, now CTO of Group 47; and myself. The objective was to discuss the same ideas Rob and I had tried to advance 20 years ago: delivered content should control the TV display, so that the best representation of the filmmaker’s work can be seen.

Nowadays, of course, we have smart TVs, the Internet and ways of passing signals to-and-from our houses to absolutely make it possible to have such controls implemented. But it’s important to note that in the historical development of smart TVs, engineers sought to provide what they thought was an image enhancement, better known as “motion interpolation.” This development solved visual problems, like judder, and made sports and reality shows look better (at least to the engineers). Unfortunately it made narrative shows look like telenovelas, removing the ability for an audience to suspend disbelief. When you read a book or hear a story on a podcast (or even on the radio!), your mind fills in the image, and broadcast images, at least in narrative storytelling, need to do the same thing for audiences to buy-in to the experience. Of course, motion interpolation can be turned off manually in many TVs. But whose parents are going to go deep into the menu settings to do something they don’t even know about?

"This new momentum will finally enhance the work that our camera teams do on-set, as well as those workers in the post-production community, ensuring that creative intent is paramount all the through the content supply chain."

- Steven Poster ASC

Which brings me to Netflix, a streaming platform whose roots in leading-edge technology have helped to foster an internal culture that seeks to preserve artistic intent. Netflix, in all its infinite wisdom, has finally made good on the ideas our group first advanced decades ago. They call it “Calibrated Mode,” a new feature developed by Sony picture quality and device experts in collaboration with Netflix color scientists and available on Sony’s new Bravia Master Series A9F OLED and Z9F LED displays. Michael Keegan, manager, partnership outreach at Netflix says, “It’s a static set of display tuning values that gets the displays to look exactly like they do in post,” i.e., as the filmmakers intended, with precise colors, accurate dynamic contrast, proper aspect ratio, and no motion interpolation.

And this technology from Netflix and Sony is just the beginning. Given the ferocious competition in consumer electronics, we will no doubt be seeing similar technology built into smart displays from Samsung, LG, Vizio, etc. We’ll also see the suppliers of screen video, and perhaps even the broadcast suppliers, adopt the same controls on their content as well.

This new momentum will finally enhance the work that our camera teams do on-set, as well as those workers in the post-production community, ensuring that creative intent is paramount all the through the content supply chain.

Or as I told Rob Hummel at the HPA panel this past winter, “Our patience has finally been rewarded, my friend.”

Good things can come to those who wait.