Home » Features » Interviews » Visionary »

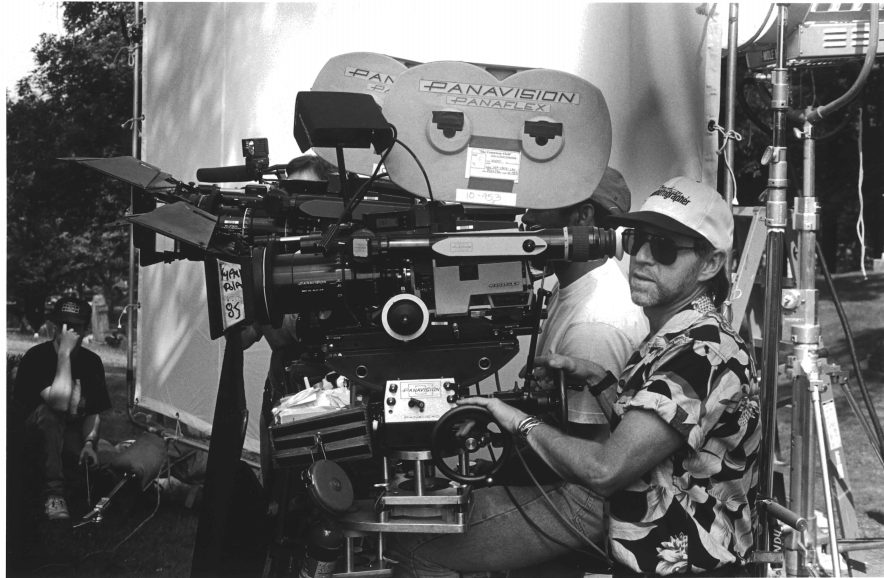

LIFELONG LOVE FOR IMAGES

Transfixed by cameras since childhood, Steven Poster ASC has since established himself behind the lens on some of Hollywood’s biggest productions – and has no intention of stopping anytime soon.

There aren’t many 12-year-olds who know for certain what they want to be when they grow up, but Steven Poster ASC was one of the lucky ones.

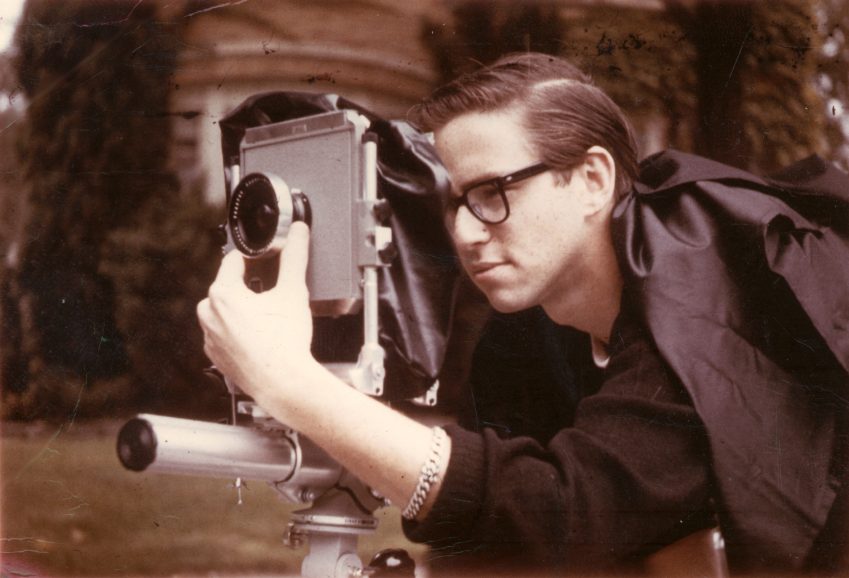

An avid interest in stills photography had turned a kid with a box Brownie into a teenager “knowing it would be my life’s work”.

He spent $100 on a Rolleiflex aged 14 but it was when a new neighbour moved next door to the family’s Chicago home wearing a light meter that he decided he wanted to shoot movies.

“I just thought he was the coolest person I’d ever seen,” recalls Poster. “He was a CBS newsreel cameraman and owned a film lab in town and he became my mentor. I loved movies and I loved photography and just needed some way to connect the two.”

The cameraman insisted that Poster study stills photography at college, saying that everything about cinematography stems from that first artform. He also insisted that Poster steer clear of news.

“I’m a black-and-white street shooter and have been since high school,” he says. “I like to think of myself as young Vivian Maier (whose work Poster has helped to posthumously curate). Clearly, I am nowhere near her level but as soon as I start to read a script, I start seeing shapes and the integration of shapes that make an interesting composition. And as I continue to read, the palette of the project becomes clearer in my head.”

Foot on the ladder

In the early ‘60s he studied at Southern Illinois University, Los Angeles ArtCenter College of Design, and the Institute of Design at the Illinois Institute of Technology.

In his senior year he went into a boutique commercials house for what he thought was an assistant camera job. “They said they’d seen a film I’d shot in college and hired me as cameraman.”

Two weeks later Poster shot his first national commercial, the first of dozens of spots, medical and corporate videos: “whatever I could get my hands on to shoot, all in 16mm.”

In this period, he was hired by Michael Mann’s production outfit in Chicago and worked with the soon-to-be Miami Vice director on commercials and documentaries, soon getting his union card.

Poster bonded with Vilmos Zsigmond ASC when the pair were assigned to shoot a commercial for a tyre company at a freezing airfield in northern Minnesota.

They ended up sharing an agent, so when Zsigmond was preparing to shoot Close Encounters of the Third Kind in 1977 he nominated Poster to join the project.

“For the first three weeks Steven Spielberg never let me do anything on camera. I was just the Chicago standby guy until he let me have a scene (a party in a backyard) to see what I could do.”

The 28-year-old director liked what Poster did, so the next day he gave him five more shots to do. These included the famous sequence near the film’s beginning when the toys in a suburban front room appear to come alive. That constituted Poster’s first official day as a second unit DP.

Later, with Zsigmond busy prepping the lights for the spaceship filmed under massive dirigible hangers that features in the film’s showstopping climax, Poster was asked by Spielberg to shoot the film’s evacuation scene.

“I took a gaffer down to Bay Minette over the Mobile and Tensaw Rivers and lit over the weekend and suddenly there I was on the Monday in the evacuation scene with 1,500 extras, plus cows, chickens and horses, along with cars and arc lights and a giant crane.”

Working with Scott

A few years later while still on second unit duties, he got a call to shoot for one night on a sci-fi film in downtown LA. Two other DPs had reportedly tried to photograph this scene but not to director Ridley Scott’s satisfaction.

“It was of the ‘Spinner’ flying police car landing in the 2nd Street Tunnel,” Poster says. “The studio asked me to go get it but gave me no lighting, just a water truck.

“I did what I would normally do and got creative. I took all the cars and any trucks we had and lined them up on the other side of tunnel with their lights on and shot a couple of time as car passed through.

“The next day I got a call saying, ‘Ridley wants you to come in tonight’. I got three weeks of second unit additional photography on Blade Runner.”

Notably this included the dressing room scene where Zhora (Joanna Cassidy) is beaten up by Deckard (Harrison Ford), dives through the window (played back in slow motion) and is shot dead.

“It was exciting to be able to work with Jordan Cronenweth ASC who was one of sweetest human beings and a big break for me in terms of getting to see how it was all done on a big set.

“I also learned a lot from Ridley. He has the ability to change every shot and still make it work.”

In 1987 they made the neo-noir thriller Someone to Watch Over Me starring Tom Berenger. “At that time, he was trying to prove he could do a lower budget movie on time and on schedule. Ridley works so fast and is so creative. He uses ‘Ridley grams’, little diagrams of what he wanted me to set up.”

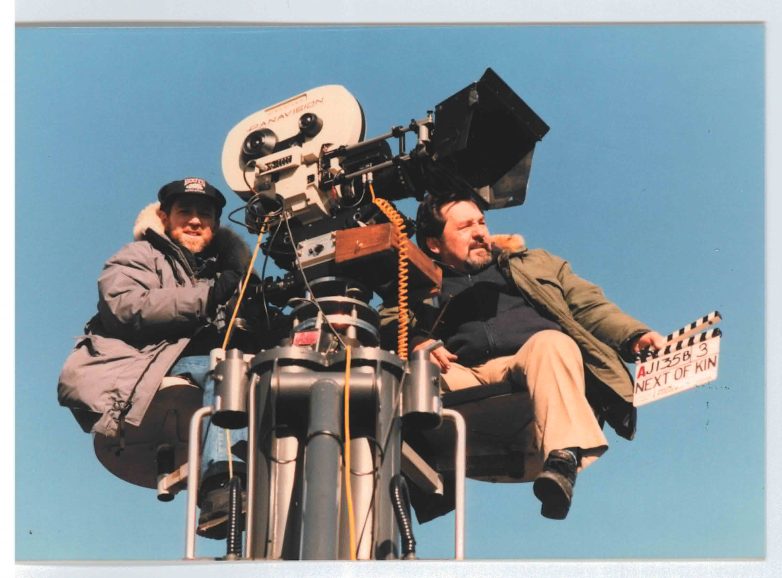

Poster also worked second unit on a couple of John Carpenter classics, Starman (1984) starring Jeff Bridges and the Chinatown footage for Big Trouble in Little China (1986), and also on Mark Rydell’s The River (1984) starring Mel Gibson and Sissy Spacek.

His move into features as cinematographer included 1979 TV movie Beggarman, Thief, Blood Beach (1980) which followed in the wake of Jaws, and Blue City (1986) starring brat packers Judd Nelson and Ally Sheedy. His work on 2005 TV movie Mrs. Harris was Emmy nominated.

Patrice Leconte wanted Poster to shoot Une chance sur deux (1998) starring Jean-Paul Belmondo, Alain Delon, and Vanessa Paradis, and was by all accounts the first time that French guilds had allowed an American to photograph a movie shot in the country.

Lensing Madonna

Of Poster’s many pop videos, the standout is 1989’s promo for Madonna’s ‘Like A Prayer’. Featuring the singer dancing in front of burning crosses and kissing a statue of a Black Jesus who comes to life in a church, it was banned by the Vatican.

“It was a pleasure working with Madonna. She was on the set the whole three days and she definitely had a creative contribution with director Mary Lambert. It was shot more like a narrative than a promo and photographically more like a feature. I had no idea it would be controversial. I’m a Jewish kid from Chicago. What do I know about stigmata and burning crosses on San Pedro hills?”

Cult hit Donnie Darko (2001) made Poster’s name. The strange tale of a teenager (Jake Gyllenhaal) who nearly dies when a jet engine crashes into his bedroom turns surreal when he experiences hallucinations including of a man dressed in a disturbing rabbit mask. It shouldn’t have worked, and that it did is down to the collaboration between Poster and 23-year-old debutant writer-director Richard Kelly.

“I spent five days just with Richard in my house reading the script together so that we could really understand what we are doing,” Poster says. “By the time we’d finished we’d shot-listed for every day so when got to the shoot we breezed through it in 22 days. It was all planned out very precisely. He had some ideas that were a little bit over the edge such as rotating the camera, which we did a couple times, but I talked him out of doing that too much otherwise it became a gimmick.”

Kelly wanted to shoot anamorphic widescreen, but the studio was worried about the cost of additional lights (than for spherical lenses). Poster told them that a new Kodak ASA 800 stock (Vision 800T 5287) was twice as sensitive as older stock and would eliminate needing more light. Also, he could compose scenes in the house set without seeing the low ceiling and therefore rig more fixtures onto it and move faster.

“It was all BS. I mean, it was correct, but I’d never even tested the ASA 800. To this day it remains the only film entirely shot on that stock (which Kodak discontinued in 2004).”

Donnie Darko marked the first collaboration between Poster and Kelly, who went on to work together on the features Southland Tales and The Box.

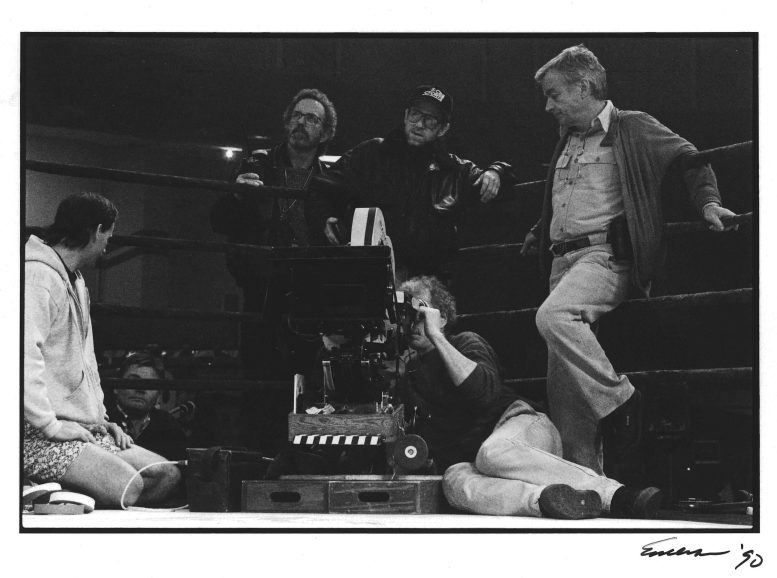

Banter with Brooks

Poster was able to work with one of his comic heroes, Mel Brooks. Poster had written him a fan letter aged 12 when Brooks’ classic ‘2000 Year Old Man’ sketch was released as an album.

“I knew every line by heart,” he recalls. “He even wrote back a thank-you note. When Life Stinks came up, I’d just got back from Rocky V which was such a miserable shoot I was going to take the summer off and recuperate. When I got the call that they needed someone to start immediately I couldn’t say no but I did want to make a deal.

“I told Mel that I knew from all my DP friends that you yell and scream at cameramen. ‘I don’t mind,’ I said, ‘but you also gotta be nice’. I got the job, but Mel would come in every day and yell ‘You don’t know comedy! You’re costing me millions of dollars!’ I just laughed. It was like having the 2000 Year Old Man yelling at me.”

Between 2006 and 2019, Poster was president of the International Cinematographers Guild (ICG, IATSE Local 600) and remains on the board, guardian of a legacy of which he is proud.

“I’ve always been committed to trade unions and the period I was president of ICG coincided with the introduction of digital. I’d been involved with plans to develop early high-definition cameras with Japanese broadcaster NHK, Sony and Panavision so I saw digital coming down the track.”

Poster (a former ASC President) was instrumental in forming the ASC’s new technology committee, and then bringing that education into the ICG once it started to secure jurisdiction in the digital field.

“Digital gave us control over images we never had before,” he observed. “It was essential that crews and craftspeople understood digital methods and took control over them so that the original intent of the visuals is maintained throughout the process. We started that at ASC and brought it over to ICG, developing our own training.”

He adds, “I may have got a reputation for being anti-digital, but I was just trying to get it better.”

His commitment to the union took him away to an extent from day-to-day cinematography, but he managed to shoot crime caper Flypaper (2011) and Amityville: The Awakening (2017).

Earlier this year, aged 79, he shot horror film Scared To Death for director Paul Boyd. “It was a wonderful experience,” he says. “I may be one of the oldest cameramen in Hollywood, but I sure had them running after me.”