Behind the glitz

For the first time since 1960, the unions representing actors and Hollywood writers are staging a simultaneous strike. The world watches with curiosity, wondering about the implications, eventual resolution and what it means for productions outside of the US.

Amidst the dazzling lights of Hollywood, an enthralling tale of creative rebellion and unyielding determination unfolds as writers and actors claim the spotlight. Fuelled by passion and united in purpose, they embark on a daring quest for recognition and justice, shaking the very foundations of the entertainment empire. Behind the scenes, alliances form, secrets are exposed, friendships are tested and people with purse strings must deal head on with their demands.

Regrettably, this dramatic scenario is not merely a teaser for Hollywood’s next blockbuster; it’s an all-too-real situation.

The American actors’ union, SAG-AFTRA, began a work stoppage on 14 July due to an ongoing dispute with the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers (AMPTP). This followed a prior Writers Guild of America (WGA) action, contributing to a broader array of conflicts in Tinseltown.

Not since 1960 have writers and actors simultaneously gone on strike. During that previous work stoppage, the unions secured residuals, industry healthcare and pension plans, benefiting a multitude of Hollywood workers. Presently, writers and actors find themselves once more on the picket lines, again engaged in a battle with the studios concerning fair compensation in the face of new technological advancements, such as artificial intelligence (AI).

British director Jim Field Smith, whose most recent credits include dramas Hijack (Apple TV+), and Litvinenko (ITV) remembers the WGA strike that ran 100 days from late 2007 to early 2008, when he was about to direct his first DreamWorks film, She’s Out of My League.

Now, 15 years later, he believes this latest strike has been looming for some time.

“I think, to a certain extent, everyone saw it coming,” Field Smith says. “You can’t have a boom like we’ve had without there coming a point where people start questioning who is and who isn’t benefitting from this boom. Traditionally if you made a show in America, it would be syndicated or repeated and then you’d be paid for that as a writer, creator or actor. Now we’re in a world of streaming, where rights are being bought out in perpetuity globally with no repeat or syndication fees.”

DP Karina Silva (The Mandalorian) says she’s been “personally affected” by the sharp drop in productions not only in the US but around the world. “This climate of uncertainty has made everyone a bit more conservative in terms of productions,” she adds. “I mainly work in commercials so my work has dropped to about 2/3 of the amount I used to get pre-strikes. I have family members in the business who do TV and films and their work has come to a complete stop. I think people who work in that field have it much harder than I do.”

One of the key accusations levelled at the streaming companies is that they maintain data secrecy, which creates accountability issues, as writers and actors go uncompensated for their contributions toward a production’s success.

“Subscriber numbers will go up as a result and the company makes more revenue – you’ve been directly responsible so you might reasonably want a piece of that,” Field Smith says. “I don’t think they are being greedy or grabby – they want to be rewarded proportionately. It’s a new version of Hollywood accounting.”

He gives the example of My Big Fat Greek Wedding, which he says, by “Hollywood accounting”, is still losing money somehow, even though it made $360 million, and it cost $5 million to make.

“The studio will say it costs this much per year to keep publicising that film or keep maintaining its assets of that film, or it’s still in debt because of reasons X, Y and Z,” Field Smith continues. “Financial leadership of corporations will always find ways to increase their bottom line because their job is to increase value for shareholders and increase the profits of the company. The creative leadership is there to nurture talent and nurture creative relationships and try to get the best possible content onto their platform. The two things aren’t very joined up.”

As the strikes in Hollywood escalate, echoing the tensions of a civil war, the ripple effects reverberate across borders, eventually impacting the livelihoods and work prospects of other crew members in various countries. Most countries have a very different system to the US, but it’s already having an impact in the UK as Disney’s live-action Snow White and Deadpool 3 have shut down production. There are an estimated 86,000 film production jobs this side of the pond.

The head of the Broadcasting Entertainment Communications and Theatre Union (Bectu), Philippa Childs, expresses strong support for the actors and writers on strike, stating that many of its members have experienced the repercussions of past US strikes and are rightfully concerned about their future. “These concerns are compounding what has already been a very challenging period for film and TV workers in the UK,” she adds. “We urge the AMPTP to tone down the rhetoric and to negotiate realistically and in good faith to bring talks to a successful resolution.”

Field Smith says “there’s a general nervousness” among UK subsidiaries of American studios. “With production halted in the US, many anticipated a boom in European production, but it hasn’t materialised due to studio concerns about their position,” he adds. “Writers, actors, directors, and producers largely support the strikes, potentially leading to a downturn in industry employment. There won’t be enough non-guild UK or European production to offset the impact of the strikes, which I think will be felt globally.”

According to a UK agent representing an actor currently working in the US, their client has been fortunate due to securing deals that fall outside the SAG agreement. “They have a waiver to do a certain amount of work with small independents and have managed to get two weeks paid leave which started as the strikes began,” she says. “They are also allowed to do paid clean-up work, such as ADR – but this is not the norm.”

Cinematographer Markus Mentzer (I Think You Should Leave with Tim Robinson) says even fewer crew members than actors (ACs, grips, electricians) are in work. Luckily, for him, he has been “working in the indie space for years, so working on indie SAG-waver productions feels no different. “Hopefully it is an opportunity for all of us to shoot projects that we have always dreamed about,” Mentzer says. “If you have friends who have always had a passion project waiting in the wings, now is the time to shoot it. Everyone wants to help.”

He says that for indie projects, his hope is to “crew members that want to be there” and are willing to go with the flow. “I think it’s more important than ever for DPs to manage people as department heads, taking care of crew and letting productions know what the issues are,” he continues. “I think there are productions that will try to take advantage of the current situation by underpaying crew, and it is just not acceptable.”

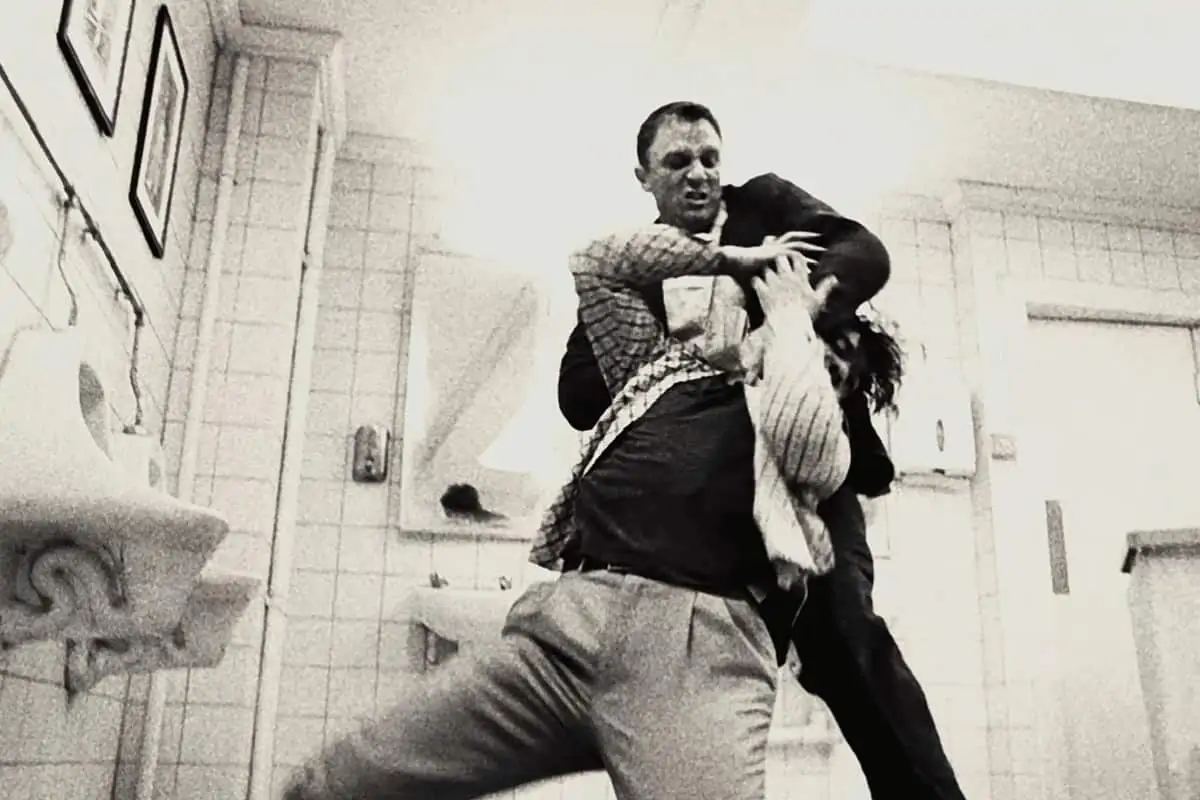

British actor and SAG member Tamer Hassan (Layer Cake) has also thrown his weight behind the fraternity.

“I’m not on a job at the moment, but I’m supporting my fellow actors by going on strike because I find it absolutely disgusting,” he says. “It’s already challenging for jobbing actors to make a living, pay bills and put food on the table. Now we have this issue with AI – our images are being used without compensation and that is theft. Some A-list actors make $20 million per film, while Hollywood studios spend $75,000 a day on productions. The journeyman actor earns around $26,000 a year, which doesn’t even cover their medical insurance.”

One gaffer, who wishes to remain anonymous argues that “some actors need a reality check” when it comes to arguing their rationale for striking.

“I read that 94% of the people on strike are background artists,” he says. “If you’re an actor in Hollywood and you’re struggling to make $26,000 a year, you need to change careers. You can earn $20 an hour in Starbucks.”

Ed Moore BSC, who worked with Field Smith on Hijack, is supposed to be working on the second series of hit Apple TV+ show Silo. However, there’s a hiatus on that series and he has no idea when he might be needed again. “The first season was a huge success, and we were several months into shooting season two – but it’s very difficult to say how it will resolve itself,” he says. “I’m not surprised it’s come to a head because things have been hanging in the balance for some time. The vast majority of the actors and writers are not incredibly wealthy stars. They’re jobbing freelancers who are intrinsic to the success of the projects they work on and deserve terms commensurate with the huge financial rewards the AMPTP members have seen.”

Field Smith agrees and says when people love what they do, people take advantage of them. “I think that’s what’s happening here, because there are people that will write and they love to write so they put up with bad terms. It’s got to the point where literally people can’t afford to live or afford to provide healthcare for their family and that’s a really serious issue.”

Mentzer says it’s reaffirming to know that the current challenges facing actors and writers are the same issues cinematographers and crew have been talking about for decades. “We are all artists and craftspeople with a skill set that has been honed by experience, a skill set that keeps productions on budget and on time,” he says. “We deserve to get compensated accordingly. We also deserve an increase in compensation for projects that initially have lower budgets and pay, but then become successful financially.”

Of course, there are other players in the ecosystem that have to adapt to the change in circumstances. 4Wood TV & Film in Wales exists to create sets for film and HETV, so a fairly significant proportion of its work comes from the inward investment from Hollywood studios and producers. Managing director Graham Webb, says the impact has been two-fold. “Firstly, it’s the drop off in new enquiries and briefs from this side of the industry,” he adds. “And secondly, it’s in existing projects that have been paused or pushed back.”

However, Webb says the company has been “fairly lucky” because for the last year it’s invested in diversifying the business. This includes work in theatre and live events. “The thinking behind this was simply that we have the skills, in-house talent and facilities to make this work, so why wouldn’t you?” he continues. “But with the unexpected turn of events this year, it’s given us other avenues to pursue. We have also just started to introduce a set storage service.”

Looking to the future, there’s a fear among some that the impasse will get worse before it gets better. However, Silva says she’s not sure how much worse it can get.

“I do think this will be a long strike and by that I mean these issues will not be solved quickly,” she says. “On one hand its heart-breaking because so many people have lost their jobs and/or are working a lot less which makes it very hard to live in a city like Los Angeles. But on the other hand, I know how important these issues are. I don’t think SAG or the WGA will give in easily, nor will the studios. It is a very uncertain and troubling time.”

However, Moore is optimistic because it doesn’t help anybody to prolong the stand-off.

“It can’t go on for too long because not only do people need to work, you can only get so much from existing shows,” he says.

That’s something everybody can agree on.