Secrets of the Master (Part 1 of 2)

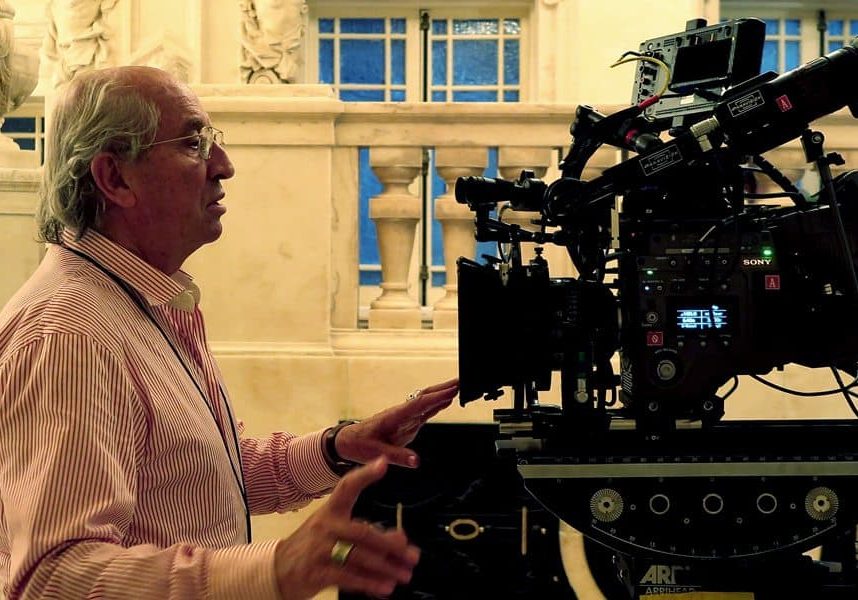

Vittorio Storaro AIC ASC / Café Society

Secrets of the Master (Part 1 of 2)

Vittorio Storaro AIC ASC / Café Society

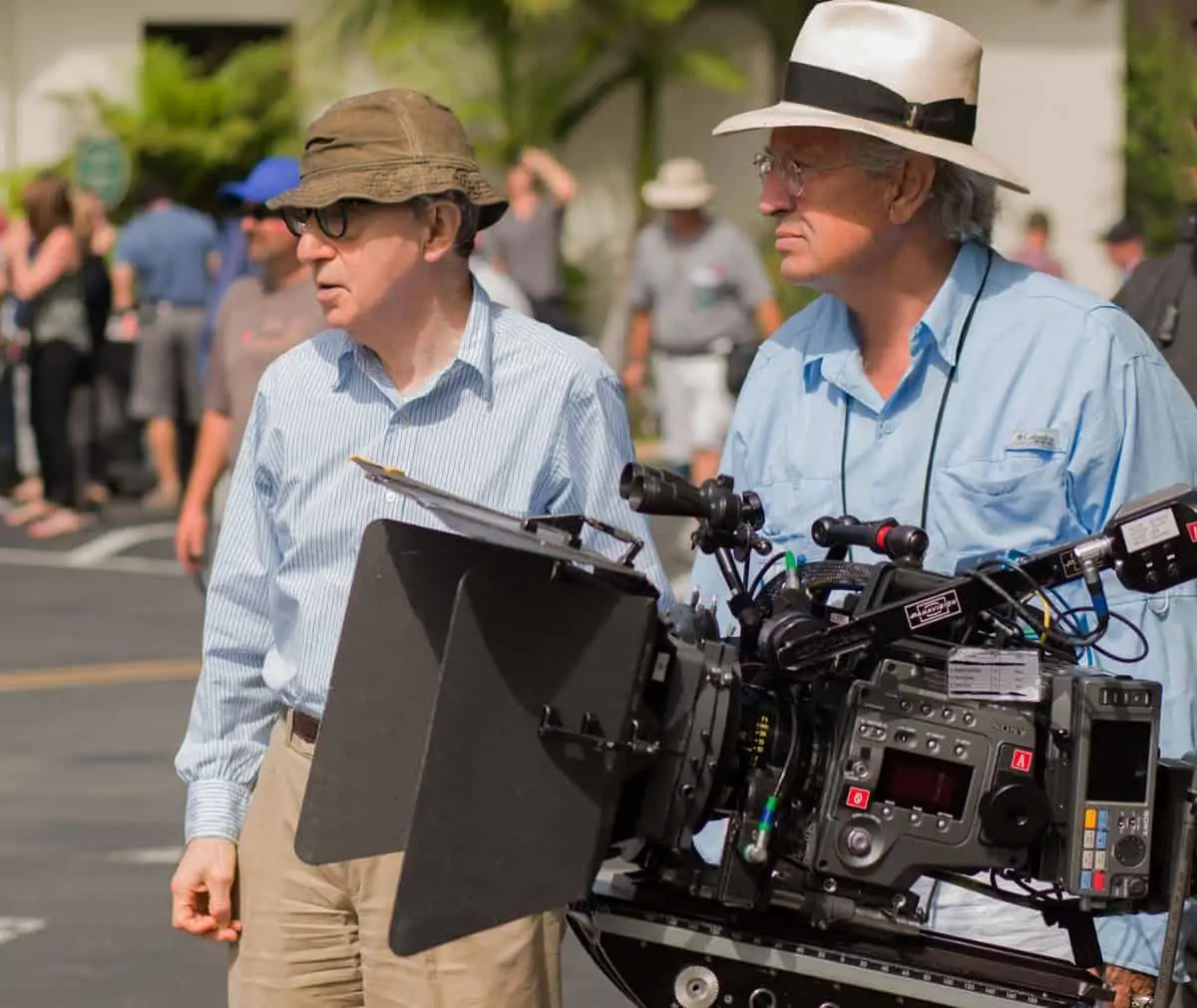

Triple Oscar-winning cinematographer, Vittorio Storaro AIC ASC, shares his experiences of shooting Woody Allen’s romantic comedy Café Society digitally, and offers some sage advice for up-and-coming cinematographers.

Although I have used High Definition video and digital capture technology for well over thirty years, Café Society was my first real experience in long-form digital capture. I wanted the opportunity to express my personal views about the many different aspects of digital cinematography on this production. I perceive, and worry, that some cinematographers today do not feel they need to know much about the technology they are using, the history of cinema, the visual arts, nor, perhaps, cinematography in the future. I hope what follows will be of interest and help, particularly to younger cinematographers who are at the early stages of their careers.

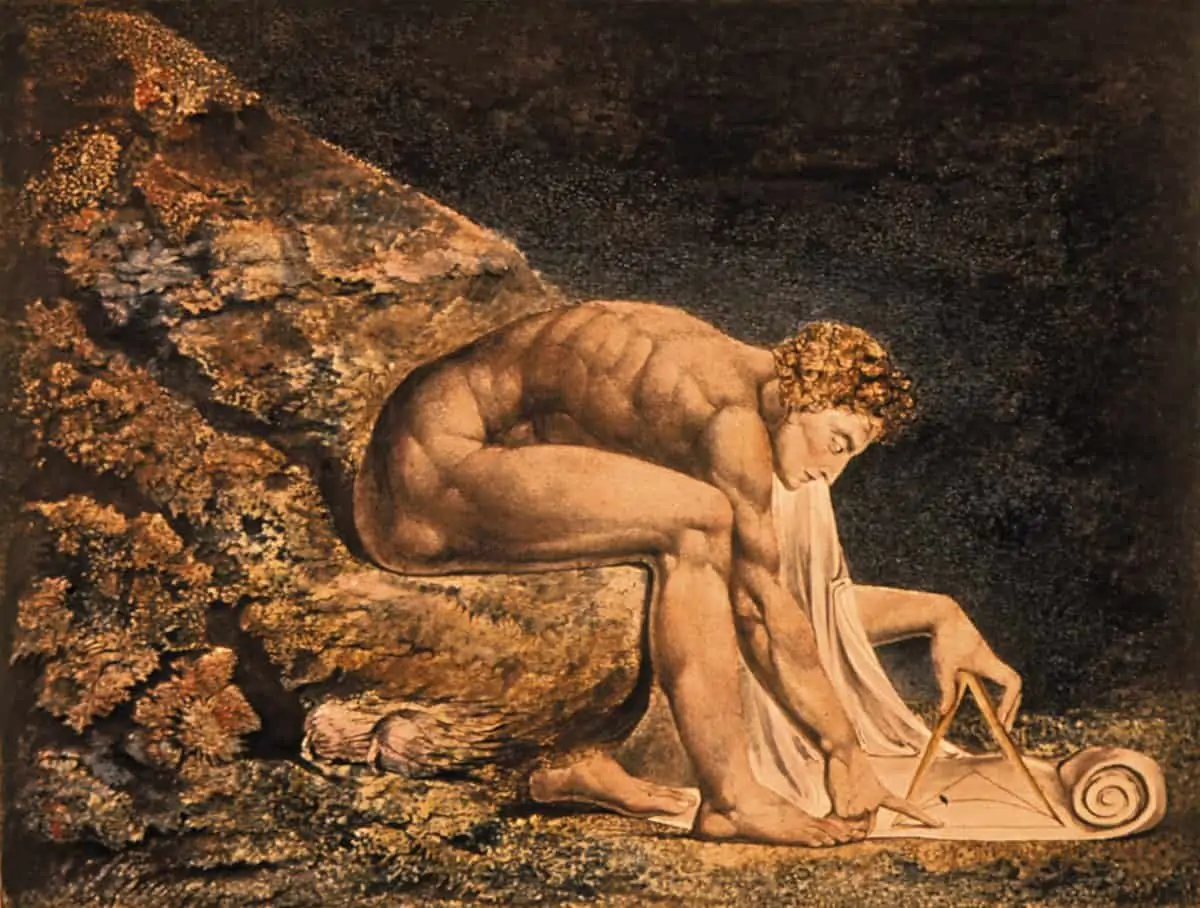

Human beings have expressed themselves using visual arts for millennia. They painted graffiti on the walls of caves, then on wood, canvas, photographic and cinematographic emulsions – in B&W, colour, widescreen, 3D stereo and 360-degrees – using analogue and, more recently, digital means.

The “medium” wasn't and isn't the most important thing: it changes in different periods of time. But, the “idea” was, is and will always be the main concern of the human mind, and this should be exactly so for the cinematographer.

I do not believe that cinema is really different in either analogue or digital form, so long as we carry history, knowledge and a genuine love for the arts into our work. Whatever the medium we choose as cinematographic artists, we have the means, and we must remain determined, to express ourselves in ways that can give new purpose to our own creative lives and evoke emotions in those who watch our work.

A) Cinematographic ideation – the psychology behind the formation of visual ideas and concepts

I believe that the research and study of paintings, photography and other historical sources, are very useful, if not essential, in helping you to arrive at the basic visual idea for a production.

Café Society follows Bobby Dorfman, the youngest son of a Jewish family in 1930s New York City, who moves to Los Angeles to work for his uncle, a talent agent, where he falls in love with his uncle's assistant. She, however, is in love with a married man and she has to decide between her two suitors.

Every film needs its own vision, particularly in the electronic era, when everybody can see images whilst we are recording them. I gave the story of Café Society a specific visual structure. Here was a production that is told not only by the characters in 1930, but also by a narrator. The voiceover that accompanies the imagery covers two contrasting worlds: the Jewish cultural world of the Bronx in New York, and the Hollywood star system in Los Angeles.

1) My first thought was to visualise New York in a low chromatic range, with dull lunar tonality. This was inspired by the photography of Edward Steichen and Alfred Stieglitz, as well the paintings of Georgia O'Keeffe and Ben Shahn.

2) It is from this vision of New York that the protagonist, Bobby Dorfman, moves to the sunlit world of Hollywood, where he meets his Uncle Phil, a film industry agent.

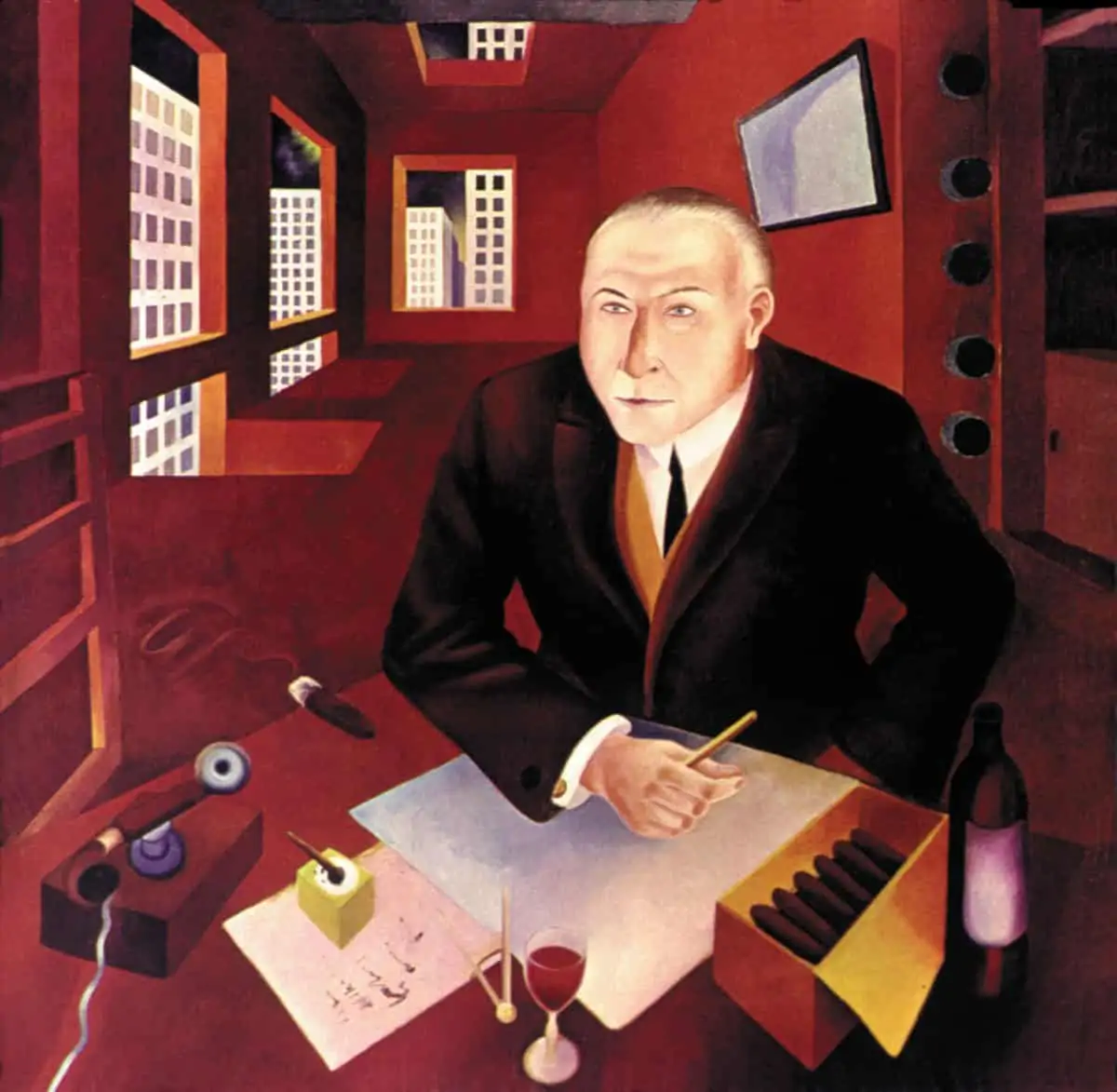

Post-expressionism was the predominant artistic movement of that time, and influenced all of arts of that period – theatre, music, photography, cinema, painting and even comic strips. It was a time saturated by the work of painters such as Otto Dix and Edward Hopper, and I felt these could have an imprint on the visual language surrounding the star system in the production of Café Society.

When the action returns to New York, the story takes Bobby into his brother's nightclub – the more sophisticated, aristocractic and luminescent world of New York’s café society, which is well represented by the Art Deco paintings of Tamara de Lempicka, who was the first woman artist to also be a glamour star.

Literature and music can take many variations, and I believe that the language of light has similar possibilities. It can have energy waves that create specific emotions. But it is not enough to have one single idea though an entire movie, and it is quite another thing to take the ideas from your mind and materialise them into moving images.

B) Location scout

It is absolutely essential for the cinematographer to see the location with the director and the production designer. From here you can start to determine all of the theoretical ideas from your mind. Usually, every scene in the script has loose descriptions such as “Day” or “Night”. But inside the word “Day” there are many different moments and settings – aurora, dawn, morning, afternoon, sunset, dusk – each with different lighting tonalities and nuances that enable you to enlarge your visual vocabulary for the production.

The location scout allows you, the cinematographer, to write on the script the different times of day and to start creating a chromatic, luminous journey that underlines the events in the story. Of course, it is your job to visualise all of this through illumination, and through my work on this production I do think that the real difference between analogue and digital capture is the use of light.

C) Importance of light

A photograph is a single expression of a moment, whereas cinematography is about multiple expressions, and it needs the input of several artists to create the complete picture.

Digital cameras are now so sensitive to light (+/- 1000ASA) that we can record images in almost any location, using just the existing available light. However, available light is not necessarily correct for any given specific sequence.

And, this is the most common mistake that many cinematographers seem to be making, to the extent that most movies do not have a proper visual style for the particular story being told, and the images end-up looking very similar to one another.

It’s now almost impossible to recognise the different creative styles between different cinematographers. And, I might say, many don't seem to want to try to have their own, personal, visual style. I have even heard some young cinematographers asking one of the camera companies to make the sensor more sensitive, so they don't need to use any additional lighting on location.

Regarding the style of light, I believe it is important to research historical references from paintings. For Café Society I was inspired by several different artistic works:

According to the book entitled Colours, by the great Russian film director Sergei Eisenstein, it is possible, and in my mind desirable, to achieve a dramatic composition of colours to better visualise the drama in different scenes.

We can also consider the colour spectrum work of Sir Isaac Newton and his conceptual arrangement of colours – red-orange-yellow-green-blue-indigo-violet – around the circumference of a circle, denoting how each complementary colour can enhance the other’s effect through optical contrast. We can use this to underline each character with a specific colour. You can also consider Goethe’s Theory Of Colours, and the physiology of how colours are perceived by humans for dramatic effect.

With this sort of knowledge, we can further enlarge our visual vocabulary for the production. We can develop more light ideas, and this is a really important element to discuss with directors and producers – not just whether we might need additional lighting for the sake of it. However, overall, we need to make sure to find an equilibrium between our creativity and the available technology.

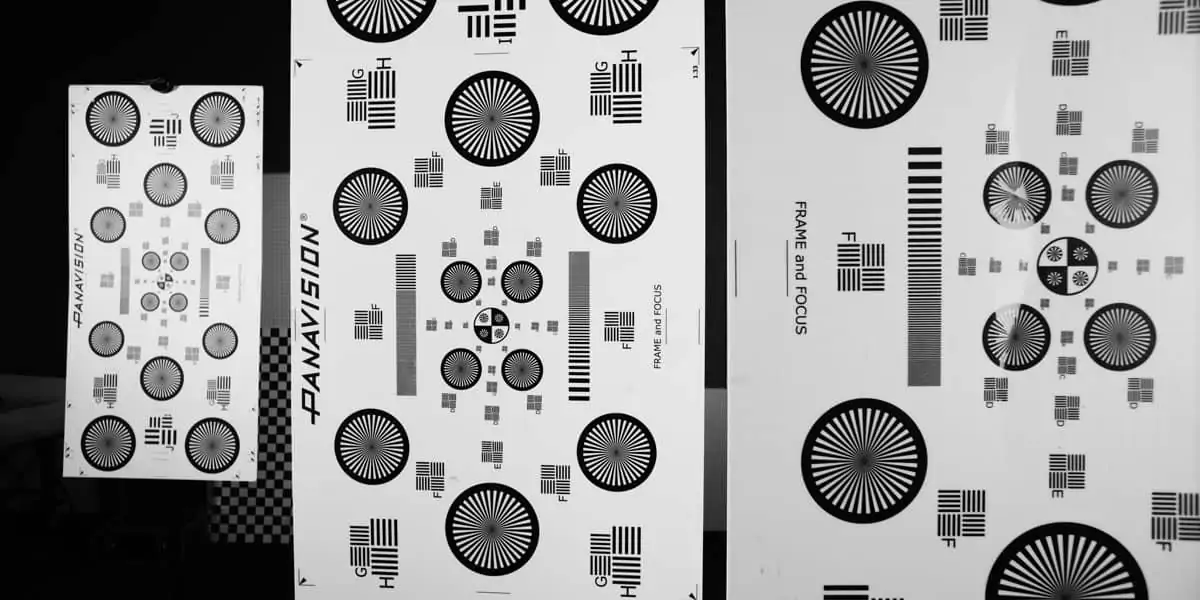

D) Technical testing

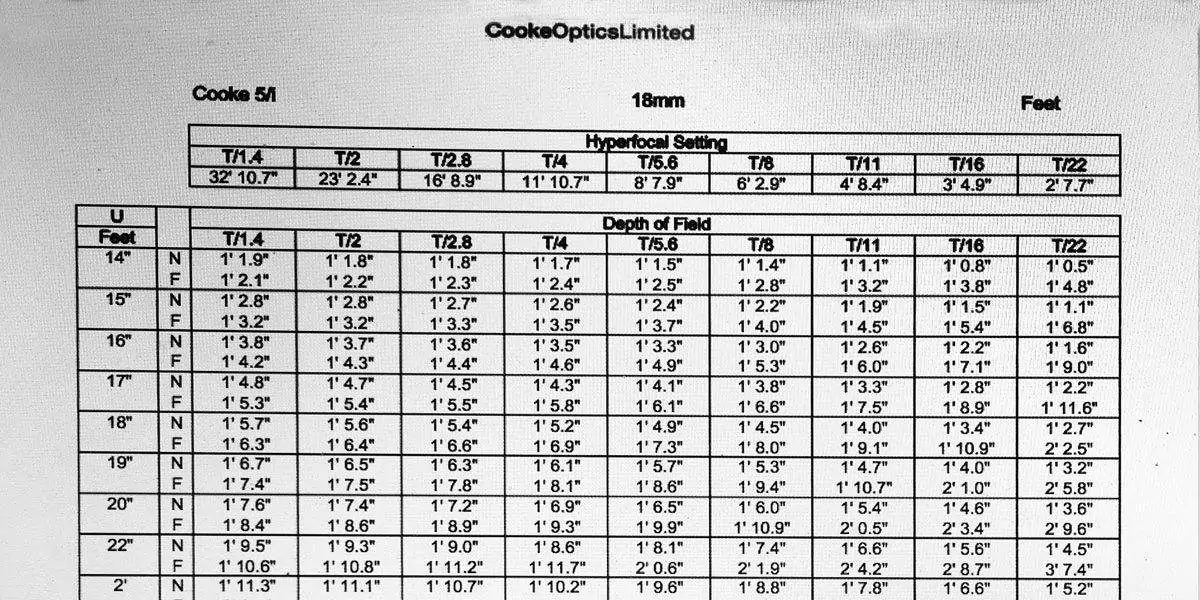

In preparing yourself for a new movie, it is important to do serious technical

tests with your chosen digital camera and lenses. You need to be sure of the central position of the focus, and how best to utilise it for creative purposes. In this respect, I would draw your attention to movies such as Citizen Kane and Son Of Saul which both use depth-of-field very effectively.

At Panavision New York, with the assistance of Chris Konash and Steve Wills, I did several important checks, particularly with the Cooke S4i lenses and their depth-of-field characteristics.

I also did some creative tests to confirm other, different parts of the cinematography and the formation of the visual ideas and concepts for Café Society, which were starting to take shape. But, to make the best use of the lighting, we need to control it.

E) Lighting & dimmer control system

Ever since I started as a cinematographer, one of my dreams was to be able to control all of the lighting from a single point. This dream was realised in 1980 during the production of One From The Heart, directed by Francis Ford Coppola.

In every other movie since then I have used a lightboard to keep all of the on-set lights under dimmer control. The benefit is that we not only keep the master down during rehearsals, saving bulbs, gels and the overall temperature on-set, but we can change the visual atmosphere within every shot.

F) Digital capture

From 1980 onwards, I started to use the small B&W video-tap that was introduced on the film camera. Reds, directed by Warren Beatty and One From The Heart by Francis Coppola, were my first experiences of using this technology. In 1983, I shot an experimental project called Arlecchino in Venice, directed by Giuliano Montaldo, using a Sony High Definition video system. In 2000, I used the Sony CineAlta, whilst I was teaching at The International Academy Of Image Arts in l'Aquila, in central Italy. In 2009, I did my first digital capture for the TV film Flamenco, Flamenco, directed by Carlos Saura. But, even with all of these different experiences, I considered that it wasn't my time to leave the world of celluloid photochemical production.

In 2015, however, for the film Café Society, I realised that the time had come for me to cross the bridge between film and digital capture.

So I convinced Woody to move together with me into this new technology.

I mentioned to him that "progress" can slow you down or speed things up. Although progress cannot be stopped, and I intended to modify it for our advantage. The Sony F65, with its 4K, 16-bit and 2:1 aspect ratio was the digital camera for us. But, I understood that I needed some additional knowledge and support to be able to perform properly with this camera.

>> Continue to Part 2 >>