Killer instinct

Seamus McGarvey BSC ASC / Life

Killer instinct

Seamus McGarvey BSC ASC / Life

The crew aboard the International Space Station (ISS) successfully capture a space probe returning from Mars. It has a particularly interesting sample inside: the first proof of extra-terrestrial life. However, instead of discovering a simple, microbial life-form – endearingly monikered “Calvin” – the team encounter something much more deadly. As the organism begins to rapidly grow and gain intelligence, the crew must kill it before it escapes to devastate Earth.

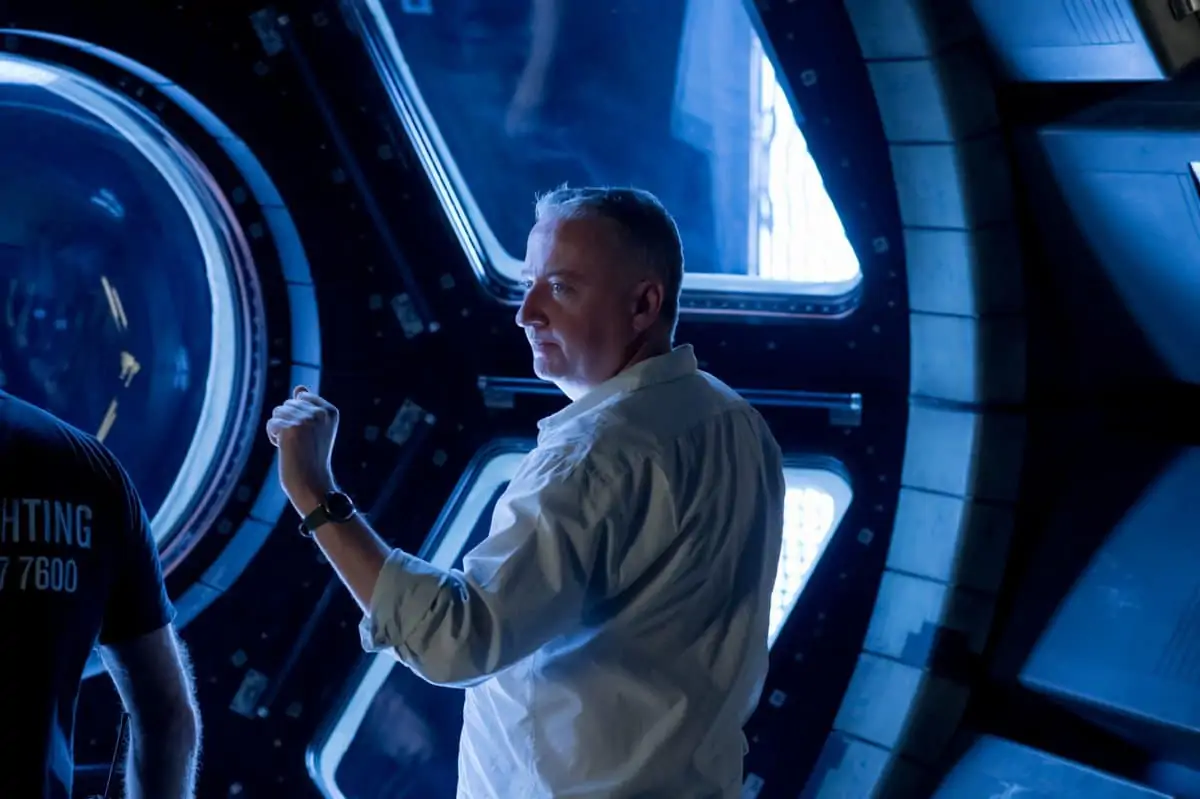

Such is the suspenseful story encapsulated in Life, Sony Pictures Entertainment’s $80m sci-fi horror, directed by Daniel Espinosa, written by Rhett Reese and Paul Wernick, and starring Jake Gyllenhaal, Rebecca Ferguson and Ryan Reynolds.

With cinematography by Seamus McGarvey BSC ASC, principal photography on the production began on July 19, 2016 at Shepperton Studios, where multiple ISS replica sets were constructed on the voluminous, 30,000sq/ft H Stage and adjacent 10,000 sq/ft R Stage. Two short additional shoots were conducted at ABC’s ‘Good Morning America’ studios in New York and on the backlot at Pinewood Studios.

Asked about his attraction to the project, McGarvey says, “I loved how taut and tense the script was – a real human story about loyalty, self-preservation, anger, fear, love, life and death – a rich seam of human emotions distilled into a pressure-cooker environment. Visually, I have always had an obsession with astronomy, space and manned space travel. Plus, I had never shot a sci-fi movie before. So all of that had an allure too.”

However, McGarvey says he was well aware of the challenges he would face regarding the photography, lighting and camera movement – given the constraints of size and space within the ISS replica set-builds – along with the task of visually supporting the notion of the action taking place in zero gravity.

“Some films like 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968, dir. Stanley Kubrick, DP Geoffrey Unsworth BSC) and Interstellar (2014, dir. Christopher Nolan, DP Hoyte Van Hoytema FSF NSC), solved the weightlessness issue by having their own gravity,” says McGarvey. “But Daniel wanted Life to be like being on board the ISS for real, and to have the actors floating around pretty much all of the time.”

In terms of Espinosa’s vision for the look of the production, McGarvey and his director considered sci-fi standards, including 2001: A Space Odyssey, Ridley Scott’s Alien (1979, DP Derek Vanlint) and Danny Boyle’s Sunshine (2007, DP Alwin H. Küchler BSC).

“What we loved in particular about Alien was the reality of their spaceship, the veracity of the workspace. It wasn’t a glimmering, shimmering spaceship, with bells and whistles, but a bit rough at the edges – not unlike the ISS, which has been cobbled together one piece at a time with different sections from the US, Japan, Russia, etc.,” he notes. “We also looked at photographs from the early Apollo missions, which have a beauty in their mixed light – the blue glow of Earth, the direct hot light of the Sun, the darkness of space, and the mixed, multiple light sources of varying colour temperatures within the ships.”

Whilst contemplating the look of the production, McGarvey also had to consider which cameras, lenses and production format would best suit the narrative, the practical logistics of the shoot, and the post production.

“Initially, Daniel was very eager to shoot on film, and to have the texture of celluloid,” McGarvey explains. “However, I managed to convince him that because of the low-light levels we would encounter, plus the tight and awkward environments within in the ISS, that it would be hard to get the T-stop I needed with film, and that it would prove problematic when to came to changing magazines on Technocrane arms through long tunnels with floating walls. So a more compact, digital camera package would be the best route.”

Although he had previously tested the ARRI Alexa 65, McGarvey had never used the camera system on a production before. He says, “I was attracted to the Alexa 65, not for what it’s known for – epic landscapes and wide vistas – but for how the sensor mimics medium format photography, its depth-of-field, the lovely way it records skin tones, and the fall-off on faces. It is a great portraiture format, with minimal distortion, backed-up by fantastic colour science from ARRI and Codex’s efficient camera-to-post workflow.”

With assistance from Panavision in London, McGarvey tested a series of large-format lenses in combination with the Alexa 65, including Primo 70s and Sphero 65s. In the end though, he opted for ARRI Prime 65s, incorporating Hasselblad glass, as “they are modern, with high-performance optics, that allow you to use wide lenses without the same distortion that you’d get on a smaller sensor. And they deliver a kind photographic result too.”

McGarvey framed Life in 2.39:1, rather than 1.85:1, as he could not only use the format for portraiture, but also harness the visual potency of the wider aspect ratio to place faces at the edge of frame, and use the empty spaces of the picture to create an eerie darkness. “As we framed either extremely wide or extremely tight, I more or less shot the entire movie with two lenses - a 40mm or a 135mm,” he adds.

The Alexa 65 was the main camera on first and second units. Alexa Minis, fitted with Primos, were used as B-cameras. Both the Prime 65s and Primos feature Lens Data Systems, which allow frame-accurate metadata about focus, iris and zoom settings to be recorded within the uncompressed ARRIRAW image stream –passing from the in-camera Codex SXR Capture Drives (used with the Alexa 65s) and CF2 cards (used with the Alexa Minis, and cloned into Codex XR Capture Drives for a better data management efficiency) to a near-set Codex Vault S and then into post production.

McGarvey also shot other sequences – such as Calvin POV shots through air vents, plus the innards of the ISS – using Codex Action Cam and Flare 4K SDI cameras, and even used an Apple iPhone 6s for the birth of a new baby daughter of one of the astronauts, streamed from Earth to the ISS.

During production, Peter Robertson operated A-camera on H-Stage, with Alan Hall as the A-camera first AC. Iain Struthers was B-camera operator, with Olly Tellett as B-camera first AC. The R-stage unit DP and camera operator was Carlos De Carvalho, with Paul Wheeldon his first AC. The on-set DITs were Francesco Giardiello on H-Stage – who helped establish a full ACES pipeline on the production, and who McGarvey describes “key cohort” in the cinematographic workflow – with Sean Leonard on R-stage. Pinewood Post, which is based at Shepperton Studios, performed the data cloning, image QC and the creation of the editorial/VFX deliverables.

"Visually, I have always had an obsession with astronomy, space and manned space travel. Plus, I had never shot a sci-fi movie before. So all of that had an allure too."

- Seamus McGarvey BSC ASC

During prep, which he describes as, “the most intense and technical I have ever been through before, bar none,” McGarvey immersed himself in working out the practical logistics of the lighting of the ISS sets with production designer Nigel Phelps, supervising art director Marc Homes, prop master Barry Gibbs, and gaffer Lee Walters.

McGarvey explains: “Because of the restricted space – such as 40ft-long connecting tunnels, less than 8ft wide – I knew we would have to integrate the interior lighting of the ISS into the sets. We designed a quite fantastic array of bespoke LED lights – low-profile, diffused, linear and circular boxes using ribbon strips – all carefully positioned or concealed, and gave them nicknames such as Medium, Large and XL Pizza, Mini Coffin, Big Coffin and Roulette Wheel. Lee also devised a small LED hand-pad, named Cigarette, that could be used beside the camera to provide gentle, diffused fill illumination on the actors’ faces. As we would be shooting scenes at different times of day, all of these lights were wired to a dimmer board, controlled from an iPad, so we could easily change the relationship of the lights as required.”

After extensive testing, McGarvey opted to soften the overall look of the LED lighting in-camera with Tiffen Glimmerglass filtration, which also had the effect of creating a pleasing halation.

To emulate the effect of direct sunlight, and the sharp shadows it creates in space, McGarvey hit actors and sets with a direct beam of light from a K5600 Alpha 18K. This single source approach also came with the advantage that exterior scenes, such as a space walk, could be shot against black, rather than traditional greenscreen – thereby eliminating green spill and making the CG set extension and background work easier for the VFX teams.

To create the ambient bounce of light coming from Earth, McGarvey used ARRI SkyPanels, arranged as large soft boxes with silks and double egg crates to channel the throw of the light. These fixtures could be changed within seconds from cool daylight to blue/green moonlight settings, making the lighting set-ups fast and organic.

If the lighting requirement proved one challenge, moving the camera and creating a permanent feeing of weightlessness was quite another. Fortunately, first AD Josh Robertson had previously worked on Gravity, with cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki AMC ASC – also a good friend of McGarvey’s – “so we were able to incorporate some of the techniques used on that production into our shoot,” he says.

Various solutions lay in suspending the actors from vertical wires (painted out in post) that fitted through a small channel in the roof of the tunnel sets, with the camera travelling on the end of a telescopic crane arm in coordination with the action. At other moments the actors were inverted on wires, facing head down towards the camera, or strapped into tuning forks. Occasionally the actors rode a platform on a GF-8 jib arm, moved subtly to create the feeling of zero gravity.

On other occasions, the actors were seated on large yoga exercise balls, kept discretely out of frame, and used their performance skills to create the appropriate appearance of weightlessness. One set, of the crew’s sleeping quarters was built on a gimbal, which could be pivoted around an axis to allow for different configurations and wire-manipulations of the actors, to help them float in and out of their sleeping pods.

McGarvey praises the work of grip Gary Hutchings, whose collaborative, advance work with the construction and art departments proved instrumental in incorporating the precise movements of the various cranes, dolly tracks and remote heads within the confined sets.

To expedite production, two camera units often ran side-by-side on Shepperton’s H and R stages. Typically, R-Stage DP/operator De Carvalho would rehearse and prep the complex stunt and wire moves, whilst McGarvey and Espinosa were shooting on H Stage. When their shoot on H Stage was complete, the pair would then shuttle across to R stage, leaving H stage ready for the next set-ups.

“We were never idle and this way of production proved very efficient,” says McGarvey. “I have known Carlos for 20 years and it was such a bonus to have his great eye and expertise on this feature. Lee, Gary and I were always migrating between the two stages, jumping between lighting and shooting and vice versa.”

Although the production of Life harnessed multiple cameras, shooting at different image resolutions, the DI grade was undertaken at 3.2K.

The final grade on Life was completed at Technicolor in LA, by colourist Steve Scott, initially with Espinosa and McGarvey in ‘live’ attendance in London and New York respectively, during ten-hour sessions over consecutive weekends. This was achieved courtesy of Technicolor’s Tech-2-Tech remote colour grading service, which allows filmmakers to view and approve identical, calibrated 2K images from multiple Technicolor facilities at the same time. The final, master DI grading sessions were completed with Espinosa and McGarvey in attendance at Technicolor LA, during February 2017. “Steve did a great job in finessing the picture for us,” remarks McGarvey.

He concludes: “I can’t adequately describe how hard it was to make Life technically. There was so much to do – setting-up the constructed environments, preparing the cameras, the lighting, the stunts and weightless choreography – as so much of the technology and the techniques were new to us. But I love the end-result and hope that, like me, audiences will feel it is a really good, cautionary tale about how we treat one another.”