The British New Wave

Letter From America / Roy H Wagner ASC

The British New Wave

Letter From America / Roy H Wagner ASC

I’m a child of the golden age of filmmaking. Well, at least one of those golden ages we speak of with such reverence – the 1940s.

As a young aspirant I was terribly impressed by the big sets I visited. Four Super Panavision cameras, with a 100-strong lighting and grip crew to maintain the hundreds of arc lamps in the green beds and arc rails. To be a director of photography with the time and money to experiment, and to produce those glorious images, thrilled me.

If you didn’t like the finished scene today, the director would approve a reshoot tomorrow. With large lighting rigs, your rigging crew would be assigned to light, test and adjust until you were happy. Wow! The circus had come to town!

One evening, riding home with my mentor, British/American cinematographer Harry Stradling ASC, I ranted on about the power he had over the final image and the range of tools at his disposal.

Several days later Harry introduced me to a tiny, white-haired man. His name was virtually impossible for me to say, much less remember, but when I had a moment with Harry he stated, “That’s a real cinematographer! He makes movies with no time, money or lighting.”

Harry suggested that any cinematographer can paint a beautiful picture given enough time, money and the right crew. The magic is when you can create illusions with just a few of the tools. It seemed an odd thing to say for a cinematographer who had everything at his disposal.

As it turned out, Harry had introduced me to Nicholas Musuraca ASC, master of film-noir at RKO Studios. I became a disciple.

Roy: “Why are your scenes so dark?”

Musuraca: “We don’t have any money for sets.”

Harry: “If you can’t light a close-up in five minutes you shouldn’t be a cinematographer.”

John Alton ASC was an avid promoter of single source lighting. Gregg Toland ASC could shoot 60 set-ups a day in B&W.

Amidst that golden Technicolor splendour, a revolution was arising out of the devastation caused by World War II. Hollywood studios could not afford to produce their huge productions in their studios. It was dramatically cheaper to move operations to Spain, Italy, France and Great Britain.

The British film industry had devised a Levy (Eady Plan) against the Americans, insisting that all revenue collected for American product must stay within the country. As I recall, the plan required a certain number of projects to be generated by British filmmakers for British theatres. The budgets were often very small, making it difficult for the old guard to regenerate their careers under the new standards. The younger journalists, craftsmen and artists, having battled a war on their own shores, were resilient and knew how to survive when all seemed lost.

Cinematographers such as Freddie Francis BSC, Douglas Slocombe BSC, Walter Lassally BSC and Oswald Morris BSC, with a background in studio productions, had been forced by the war to learn how to tell stories in real places with available light and handheld cameras. All veterans of a catastrophe that many of us saw only through their eyes. They became the authors of reportage/street-scene/documentary-style storytelling, with many real locations and non-actors.

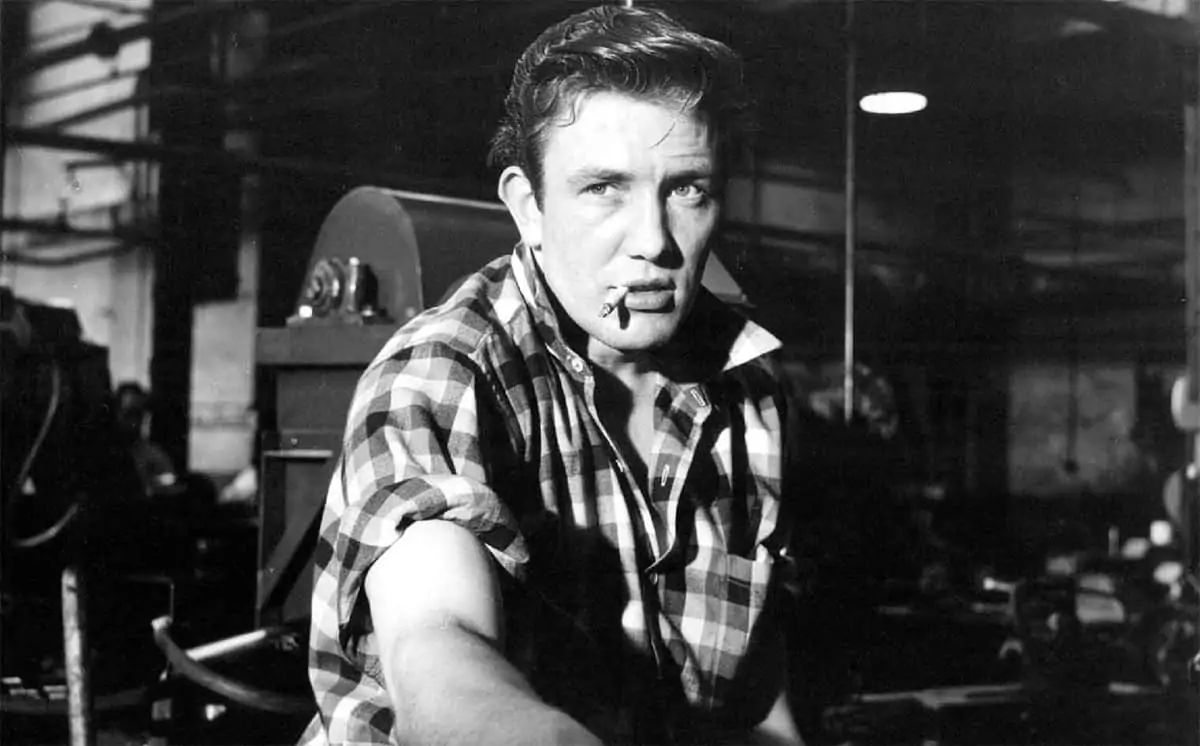

The new British cinema new wave challenged the old view of British common man. Thus, when revolutionary authors took to the streets with films such as Room At the Top (1959, dir. Jack Clayton, DP Freddie Francis BSC), Saturday Night And Sunday Morning (1960, dir. Karel Reisz, DP Freddie Francis BSC), The Loneliness Of The Long-Distance Runner (1962, dir. Tony Richardson, DP Walter Lassally BSC), L-Shaped Room (1962, dir. Bryan Forbes, DP Douglas Slocombe BSC) and This Sporting Life (1963, dir. Lindsay Anderson, DP Denys Coop BSC), the new visual grammar was supported by the next generation of cinematographers’ storytelling styles. Ealing films became the voice of the common man, much like Charles Dickens had with his observation of the curse of the Industrial Revolution, to Britain. Those films could never have been accomplished without the simplistic hardships of those budgets and a curious new style of authorship.

"Many British cinematographers remained fixed to their homeland preferring the often-limited budgets and pay scales. Many of our greatest revolutions in visual grammar still come from a loyal, society of British cinematographers, who remained in their homeland continuing to express their unique vision."

- Roy H Wagner ASC

We learned so much from the British New Wave. To me, the British reportage suggested available and natural light, wide and zoom lenses and handheld cameras, which changed cutting patterns, camera movement (counter moves against action), matching and how we saw colour. All of these choices became “tricks” to suggest to an audience that what they were seeing was real. The camera once again became a character with a particular point-of-view that had been lost in many of our Hollywood classics.

B&W now had a new relevance that could depict the character of the common man. It no longer was just a tool of economy. English Eastman Color was far superior to our stocks because of the quality of the natural light, the English cinematographers understanding of the softer contrasts, and the water used in the labs. We began asking for pre-600 film stock with the advent of high-speed stock, because that was the formula for the British look.

The rules constructed by studios and by motion picture labs, which defined what was acceptable, were destroyed by aggressive cinematographers such as Oswald Morris BSC and Geoffrey Unsworth BSC. B&W could be soft and expressive under the hands of Douglas Slocombe BSC or Freddie Francis BSC.

The French-Swiss film director Jean Luc Godard suggested that the new style “barged into the well-structured filmmaking world as if they are breaking down the walls of Versailles.”

For Americans, who had not suffered the direct attack on our nation, the revolution would occur after Europe had settled into a more comfortable revolution of Tom Jones (1963, dir. Tony Richardson, DP Walter Lassally BSC) and A Hard Day’s Night (1964, dir. Richard Lester, DP Gilbert Taylor BSC).

Many British cinematographers remained fixed to their homeland preferring the often-limited budgets and pay scales. Many of our greatest revolutions in visual grammar still come from a loyal, society of British cinematographers, who remained in their homeland continuing to express their unique vision.

The war created unthinkable devastation to a nation of resilient citizens and artists who sought to remain within their country, often working on lower budgets and yet telling stories that reflected their heritage and honoured the courage of all those who stood against hate and evil.

I’ve always admired Douglas Slocombe and the many others who could have relocated to Hollywood, but chose to remain British artists, remaining the stalwart voices of your great nation.