Guided meditation

Ron Fricke / Samsara

Guided meditation

Ron Fricke / Samsara

In movie making cinematography works with the performances, script and overall vision of the director to create a narrative. Take away the seemingly all-important elements of speech and a storyline and a film becomes a very different proposition. Director and cinematographer Ron Fricke has made a career out of non-verbal productions and during August his latest visual reflection of life, Samsara, came to the big screen.

'Big' is key to experiencing Fricke's work, much of which has been made in collaboration with producer and editor Mark Magidson. Like its predecessors, the 1992 feature Baraka and the 1985 IMAX short Chronos, Samsara was shot in 70mm and is primarily intended to be seen in a cinema.

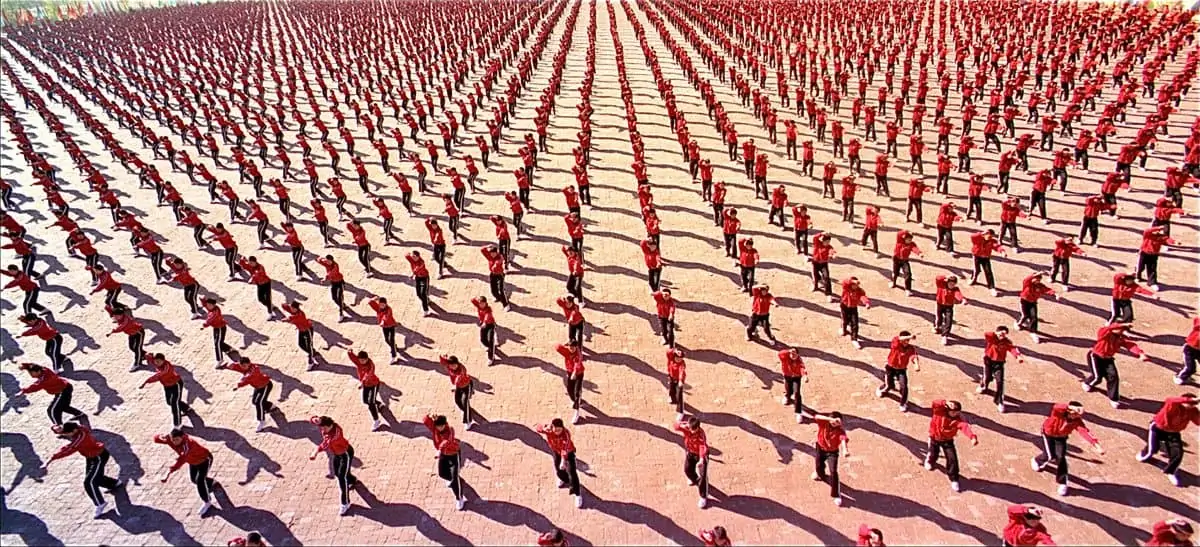

The title is a Sanskrit word meaning "continuous flow", which sums up the Buddhist belief in birth, life, death and re-birth, or reincarnation. Made over five years, three of which were spent on location, Samsara was filmed in 25 countries and presents a succession of images set to an almost hypnotic musical score.

This template was set by the pioneering director Godfrey Reggio with Koynaanisqatsi (1982), which became as famous for the music by Philip Glass as for its visual impact. Fricke is credited as director of photography and co-writer on the film and has continued to specialise in this style of moviemaking, which he deprecatingly acknowledges could be called as "glorified second unit work".

As the years moved on from Baraka, Fricke decided it was time to "dust off the passport and get back out there". Another spur was the continuing development of camera and filmmaking equipment. "After you've made one or two non-verbal films, you want to look at new territory with new technology," he comments.

Fricke sees non-verbal films as a "guided meditation", presenting images for the audience to interpret. "It's about the flow and sculpting that, moving from one subject to another," he explains. "But it's not as easy as it looks, because when you start putting a couple of images together in the edit the sequences want to say something, either good or bad. That's something we want to stay away from because we're not presenting our opinion."

Mark Magidson agrees with Fricke that the general drive of Samsara contemplates birth, death and re-birth, focusing particularly on the impermanence not only of human existence but also the world we inhabit. Even though he and Fricke are experienced in this kind of presentation, Magidson says today's visually-obsessed and interconnected society has "set a high bar" for filmmakers. "We're living in a time when people see a lot of interesting material on YouTube, so we've got to look for things they haven't seen and show it in a different way," he says. "Technology has evolved and allows us to do that, but we've got to make sure it doesn't affect the emotional impact of the material."

A key technological evolution in cinema has been the digital camera and Fricke and Magidson thought seriously about using a file-based format instead of film for Samsara. "We looked hard at it when we started in 2006," Fricke says. "But we didn't find any 4K options that were up to snuff."

Magidson adds that working with film on a multi-country shoot today is logistically tricky because all baggage has to be X-rayed, with the risk of affecting the images. "There was also the thought that digital formats can become outmoded and, although 2K was the standard in 2006, we weren't sure how it would look when the film was finished."

"Technology has evolved and allows us to do that, but we've got to make sure it doesn't affect the emotional impact of the material."

- Mark Magidson

Fricke chose the Panavision 70mm system, shooting much of Samsara on handheld 65HR spinning mirror reflex cameras. These can run from two to 72 frames and have what he describes as "a great set of lenses". A "couple of" big blimp cameras were also used, with Fricke operating all of them himself. To keep weight down, takes were shot on loads of less than 500 feet, with stocks including Vision 2, 500T, 250D and the new Vision 3.

Samsara features a wide variety of locations and subjects, from Namibian deserts to cityscapes, views over Burmese temples to African villages. A feature of the film is what Fricke calls the "staring portraits", with people looking unblinking down the lens. He says that by "staring into the eyeballs" of the subject he can attempt to reveal the essence of their character.

A Hasselblad Schneider Variogon CF 140 280 MacroZoom lens was used for most of the portraits, some of which surprised even Fricke. On the session with professional Geisha Kikumaru he decided to use a dolly track instead of the usual zoom but, as with all the sitters, he instructed her not to blink. "I don't know whether it was the lights or her make-up, because as she was staring into the lens a tear came down her cheek," he says, "but she was so cool and just carried on."

A characteristic aspect of Fricke's non-verbal work is time-lapse photography; in Samsara this includes distance shots of cars on freeways and shifting sands. He built his own motion control system for similar sequences on Baraka and updated it for the new film. The computer-controlled set-up runs on a 40-foot track or 12-foot jib, with full pan and tilt. A new feature is Preview, which allows Fricke to see how a shot is looking and make small adjustments to make sequences look as smooth and non-mechanical as possible.

Samsara went through digital intermediate post-production, starting with an 8K high-res scan to capture the large negative information. This was then outputted to 4K DCP for exhibition. Mark Magidson says this process took the 50-year old Panavision camera into the "cutting edge digital realm", with the further option of 4K or Blu-ray transfer.

Magidson observes that if he did work on a successor to Samsara he would "have to think hard about not going digital" with the cameras. Right now, though, he says, "I'm done for a while - but I said that after Baraka."

Ron Fricke, on the other hand, seems to be considering his next big adventure, spurred on by technology: "New cameras are coming on-line and I've been looking into 3D. We have two eyes and two ears so we're already set up for a 3D environment with spatial sound. And working in documentary films that makes sense, so I can see me making another world epic."