Timeline of Emotions

Racking up almost 46 million YouTube views in less than a month, Adele’s “Oh My God” music video – lensed by Roman Vasyanov ASC RGC and directed by Sam Brown – captivated audiences with its distinctive and stylish approach.

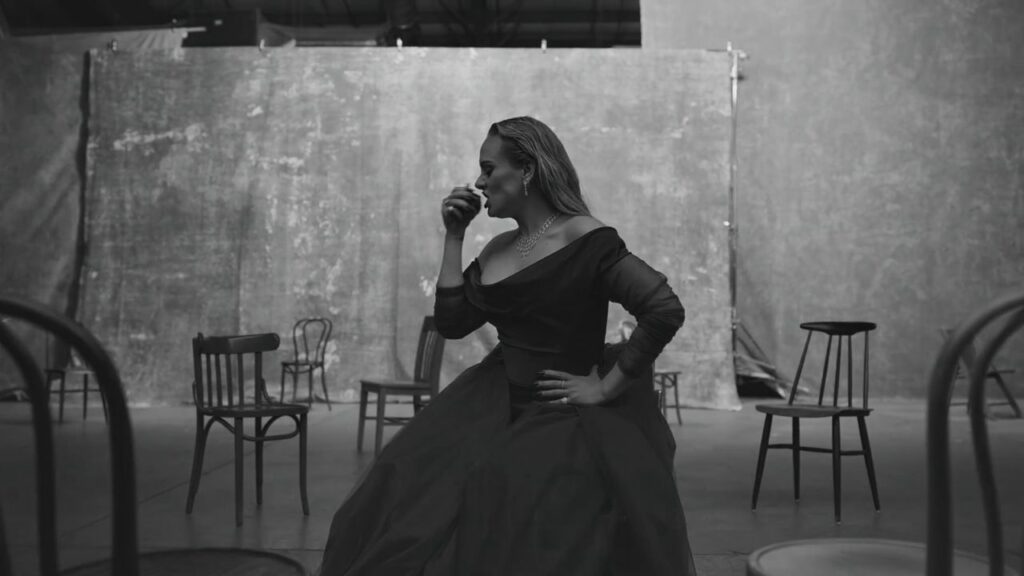

As the camera makes a seamless journey through a seemingly infinite sound stage, the mesmerising monochrome “one-shot” triumph combines an eclectic mix of visual delights, opening on an apple placed upon a chair and then capturing multiple performing Adeles, dancers, acrobats, and even a snake and a horse thrown in for good measure.

“I’m enormously proud that something which could have come across as a technical exercise just doesn’t feel that way, and Roman’s skilful cinematography plays a huge part in that,” says Brown. “Although our peers will be interested in how it was achieved, we’ve done our job if people just appreciate the video on an emotional level.”

When Adele explained the concept for the song to Brown, who had directed the video accompanying her 2010 hit “Rolling in the Deep”, she described it as a “hot mess of a song about a very emotionally complicated part of her life”. With that in mind – and enjoying the creative freedom the singer had once again given him, trusting in his visual interpretation of the song – Brown wanted to ensure the video was an amalgamation of disparate emotional states.

“I initially envisaged this collision of emotions as a vignette-like video, but then my producer Polly Ruskin asked, ‘Why don’t you do it as a one shot?’ A rather sadistic thing for her to suggest but I took on the challenge,” says Brown.

Having increasingly worked with motion control and on one-shot productions in recent years, Brown had begun to understand the technical limitations and virtues of the kit. “Filming it as a one-shot would mean it was like a timeline of emotions, moving through the different emotional states which cohabit in the same frame,” he says.

“If it was a tracking one shot there would also be multiple versions of Adele. And although I initially wanted a cast of 150, we ended up working with 20 performers, filmed on a separate day to the footage of Adele. So, we needed to creatively recycle those people in a way that fed into the video’s overriding concept.”

When planning how to approach the complex concept, Brown was confronted with an overwhelming number of choices. He began by breaking it down in a storyboard and creating tiny paper models which he set up on his kitchen table to demonstrate his visual ambitions to cinematographer Vasyanov. Brown played Adele’s track and filmed the models on his iPhone, over and over, working on the pacing, before a CG render was produced.

This precise planning was instrumental in the success of the production. “Sam had everything ready to go. The paper models, animatic, and pre-vis were the most detailed I’ve ever seen,” says Vasyanov. “When we set up everything how it was in the animatic in terms of distance, plugged it into the motion control, it just worked. We barely moved a chair. That’s why I love working with Sam – few directors are so prepared and focused while also giving you so much freedom.”

Working with the models and plans, mapped out according to the exact position they would need to sit in the LA hangar where the shoot took place, Vasyanov explored how to approach the production cinematographically. “That’s the most exciting part for me because I know how to play with light,” he says. “It’s rare to be given such a cool task – a one shot combined with beautiful choreography and Adele’s incredible music.”

Evolving ideas

With his very specific references in tow, Brown collaborated with Nu California for the first time to ensure the production design aligned with the cinematographic ambitions. “Originally, we were going to build a single long wall, but they brilliantly suggested using photographic backdrops instead which would be cheaper and more interesting as they would introduce different textures,” he says. “They were free to contribute ideas, but it was also crucial to get everything, including the position of 170 chairs, perfect and precisely measured out in the physical space to ensure everything we envisaged was executed correctly and lined up.”

But as the move Brown had demonstrated to Vasyanov was 370 feet long and beyond the boundaries of the studio space or length of motion control track, it was split up into three. The same 120-foot length of track was shot repeatedly, with elements repositioned in the frame each time, and then those worlds were stitched together. When the cinematographer arrived on pre-light day, hundreds of colour-coded pieces of tape were stuck to the floor, outlining the three passes transposed one over the other and where the dancers would be positioned as the lighting pattern changed for each sequence.

“Luckily some of the best crew in the world are in LA, so it was incredible to collaborate with people like gaffer Chris Prampin, who has worked on blockbuster productions such as Star Trek ,and key grip Ryan Busscher, who has collaborated with directors such as Michael Bay,” Vasyanov adds. “So, even though this shoot was extremely complicated, it was difficult to scare Chris and Ryan.”

Having drawn upon the stunning black-and-white work of Irvin Penn in an oblique way in previous projects, “Oh My God” marked the first time the twentieth century photographer whom Brown has admired for many years has had such a direct influence. “His work seems so contemporary to me. I was interested in that studio aesthetic he adopted, I wanted to explore how to use simple things to create a sophisticated aesthetic; something Penn excelled at. I leant on some of his ingenuity, but then what Roman created didn’t really look like Penn’s work. He took it in a completely different direction which was really exciting.”

Brown believes that when working on a project with disparate imagery such as “Oh My God”, it’s necessary to have something to bind it all together, which black-and-white did beautifully. “You need to democratise the imagery, and with black-and-white you can draw together things that shouldn’t sit together because you’re getting rid of one element of comprehension. You’re simplifying.”

Shooting in black-and-white also allowed Vasyanov to adopt a more classic Hollywood-style lighting technique incorporating hundreds of spotlights programmed through a dimmer. “It meant we could be more precise with the lighting, and it looks so glamourous and is great for the performer,” he says.

Prampin and Vasyanov used tungsten light rather than mixed sources because they needed the lamps to have the same timing when being dimmed. “I also like the quality of tungsten light on skin when working in black-and white,” says Vasyanov. “We used Creamsource Vortex8 for some backlight, built our own soft boxes, and worked with 5Ks, 10Ks, Chimera products through soft diffusions for big frames, along with a lot of ETC Source Fours to shape the light in particular areas.”

Delivering crispness and beauty

Vasyanov captured the bold and beautiful production using the Sony Venice, enjoying operating it in Rialto mode to decrease the size of the camera on top of the motion control system, meaning “when the motion control stopped there was no shake because the camera wasn’t as heavy”. “The Venice also allowed me to shoot at 2500 ISO and use a special LUT my DIT Arthur To built which simulated the look of Ilford 400 – black-and-white film I’ve loved since my early film photography,” he says.

Lens selection was partly based on size, with the 24mm Leica Summilux delivering the crispness and compactness needed. While some might look to vintage lenses, Vasyanov believes that when working with “such a strong idea with so many elements in the shot”, visual tricks are not necessary. “You just have to deliver the crispness and beauty of what is already there.”

Brown enjoyed the results the 24mm focal length lens delivered as it meant Vasyanov could not shoot too close to Adele. “This created an interesting distance from Adele and her performance; she’s only ever a wide or a loose mid shot,” says the director. “It’s unusual to film a big star and not get really close up but this makes her feel more mysterious and intriguing.”

The crew tackled a “complex jigsaw puzzle” when capturing performers moving at different speeds in the same shot. “We used the motion control unit to render some people at normal speed, but by going double the dolly speed and twice the frame rate, people moving at different frame speeds could cohabit the same frame at the same time, but they are different versions of the same people,” says Brown.

“Roman did an incredible job technically of creating very glamourous, dramatic lighting while making sure nobody shadowed anyone else and that everyone’s pathways did not interrupt or overlap in terms of their physicality or lighting. Each stage of the video has a different feel – some parts are soft light and others hard. The way it changes blew me away.”

Overcoming lateral motion blur demanded an elaborate choreography to achieve the balletic camera movement desired. Executed with the help of talented 1st AC Mateo Bourdieu, a technique of panning and pivoting around subjects kept them sharp and prevented motion blur.

“The camera move was plotted by James Sindle from ETC, who just has a natural feel for camera movement because he’s plotted 3D cameras all his life,” says Brown. “He interpreted my paper model very elegantly. Simon Wakley, who headed up motion control during the shoot, was a genius. The technical obstacles he overcame were extraordinary.”

Rather than “cheating” by incorporating foreground interventions or distractions, Brown wanted the multiple elements to be stitched together without wipes. “I haven’t seen that done too many times and for good reason because it means matching the camera’s movement and lighting of a transition and seamlessly stitching the backgrounds together. So, we needed quite a bit of CGI and manipulation for everything to look like a smooth transition. This was all handled so masterfully by ETC that I don’t know where the joins are.”

Vasyanov and gaffer Prampin also used lighting techniques to ensure the stitches were flawless. “I asked Sam if we could use slightly softer light for the stitches and then go back to strong light which he was happy to do so long as everything had a dramatic arc tying in with the concept for the video,” says Vasyanov.

Brown envisaged a “very even, almost daylight feel” to the lighting, like Irving Penn or Cecil Beaton’s soft studio aesthetic, thinking that might be most easily technically achievable. But Vasyanov assured him “every subject could be treated differently and that it could be made very elaborate”.

“I just love that it’s a series of different shots within one shot,” says Brown. “The lighting moves and changes in a very theatrical way and pulls different moods out of each scenario in a way that my original intention might not have produced, so I’m indebted to Roman for that.”

The director was also impressed by how close to the final look the footage captured by Vasyanov was when entering the grade with Luke Morrison at ETC. “I like it when a lot is achieved in camera, and we are just very soft and delicate in the grade. Instead of adding film grain, we kept it very clean and made subtle adjustments to the hue to achieve those beautiful silvery skin tones.”

Reflecting on a technically ambitious production, teamwork is what transformed Brown’s early paper models into a stunning reality. “I’ll maybe lay off the motion control for a little while I think! It can be stressful as a tiny problem can derail everything,” he says. “But if you’re collaborating with the right people, you mitigate against those things going wrong.”

Adele echoed this when she shone a light on the diligent and creative team in a tweet posted after the shoot, saying the “attention to detail from the crew was borderline hilarious – thank you so much for your patience and for pulling it all together.”

Roman Vasyanov ASC RGC was one of the top signatories of an open letter against the war in Ukraine which was signed by prominent Russian cinematographers and sent to the Russian Government.