BRUTALITY MEETS BEAUTY

Communicating the cruelty of slavery while lensing elements of the beautiful in historical drama Emancipation was a multifaceted and sizeable responsibility that led director Antoine Fuqua and cinematographer Robert Richardson ASC into new creative territory, venturing into swamps and braving the battlefield to bring the powerful story to audiences.

A unified vision of what the story needed to convey and the heartlessness it must expose was integral when director Antoine Fuqua (Training Day, The Magnificent Seven) and cinematographer Robert Richardson ASC (JFK, The Aviator, Once Upon a Time in Hollywood) were shooting Apple original film Emancipation, creating an immersive, 360-degree experience as the audience joins the protagonist fleeing from enslavement.

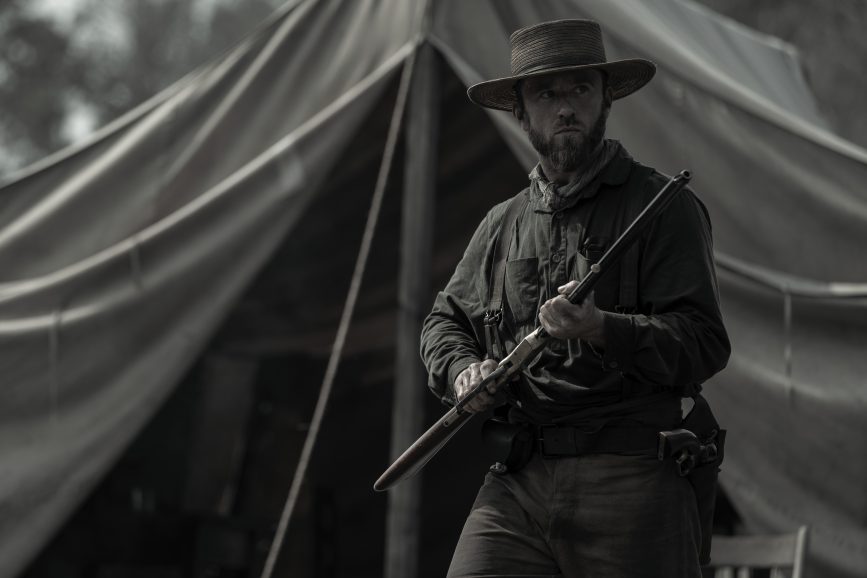

Inspired by the 1863 photos taken during a Union Army medical examination of the man known to historians as “whipped Peter,” Emancipation highlights Peter’s (Will Smith) escape from slavery and quest for freedom as he runs from bounty hunters through the treacherous Louisiana swamps and eventually fights on the Civil War battlefield. Through sharing Peter’s story, the filmmakers pay homage to the more than 100,000 Americans who became fugitives and freedom-seekers bravely fleeing from enslavement.

“As soon as I read the script, I knew I had to do it. I felt passionate about the story and the central character,” says Antoine Fuqua. “Will [Smith] – who plays Peter and was one of the film’s producers – and I had wanted to work together for a while, and I only had one person in mind if he was available to shoot this and be my partner in crafting the film – Bob Richardson. He’s an amazing cinematographer and I was honoured to work with him.”

Drawn to films highlighting important issues, Richardson appreciates it is “rare to get the opportunity to help tell stories that are meaningful”. But when Fuqua approached him about Emancipation the answer was not an instant yes. “When he asked me, I choked at first and said I didn’t want to make the movie because I hate alligators and have a tremendous phobia of snakes. But the truth of it was I didn’t feel comfortable as a white cinematographer to shoot this story, and I thought a person of colour should do it,” explains Richardson.

“But Antoine reinforced that this is not a story about one particular race or gender – it’s universal. It’s about all the issues society continually goes through. There are predators in this world and generally problems stem from money and land, from when the film is set through to what’s happening currently in Ukraine. Apple were extraordinarily brave taking this project on and were very supportive. From Apple through to the crew and cast, it’s one of the best groups of people I’ve worked with.”

With Richardson on board to lens the powerful tale oftorture, tenacity and ultimately triumph,the visual language of the film began to grow along with the concept of moving from colour into a “close resemblance of black-and-white” with splashes of colour.

“Our decisions regarding the look of the film were initially motivated by the powerful photograph of Peterwhich had an almost platinum quality. It’s black-and-white and beautiful in terms of its tonalities but it is also brutal,” says Richardson. The image – known as “The Scourged Back” and which first appeared in Harper’s Weekly – shows Peter’s bare back mutilated by a whipping from his enslavers, and ultimately contributed to growing public opposition to slavery.

Although Apple was expecting a colour film, with the help of tests graded towards a black-and-white look and midway between colour and monochrome, Richardson and Fuqua persuaded them adopting a distinct visual approach drained of colour was suitable for the story. Richardson’s view on the use of colour also shifted during this process: “I don’t mean to be demeaning about the use of colour, but for this particular subject matter, colour seemed almost like a Hallmark or Rockwellian view – it had too much information and removed you from the story.”

Fuqua and Richardson agreed that while the swamps in which some of the action would take place were lush and gorgeous, they were also extremely dangerous and “would take on a different vibe if greens and heavy colours featured.”

The almost monochrome look was also deemed powerful when capturing faces including Peter’s. “I’ve never seen a face of colour that distinct and stunning on screen,” says Richardson. “The film has a heavily desaturated feel but then you’ll momentarily see colour. And we weren’t dealing with backlight or warm light – we adopted brutal over beautiful lighting.”

Richardson carried out testing with second unit director (and production visual effects supervisor) Robert Legato ASC to help develop the LUT, moving through shifts of black-and-white to footage that was tinted. “We were immediately in sync, and tried to follow the more monochrome path,” says Richardson. “I’ve worked with Rob on a number of films and it’s an extraordinarily close collaboration. I trust him implicitly – he’s a master of VFX as well as a superb cinematographer and director and he should be heavily applauded for the immense amount he contributed to this film.”

The filmmakers also collaborated with on set colour grader Benny Estrada, examining and then making decision based on the dailies. “In the final grade with Stefan Sonnenfeld, senior colourist at Company 3, Antoine would then tell us where he wanted more light or colour and where to keep the more black-and-white look which I always pushed heavily towards,” adds Richardson.

Rhythm and colour

David Lean’s Lawrence of Arabia and the work of Stanley Kubrick along with two films shot by Richardson and directed by Oliver Stone – Platoon and Heaven and Earth – were among the productions that influenced Fuqua when constructing the look for Emancipation. “I’ve always been in awe of Heaven and Earth – the elegance of it, and the violence that went along with that and how it changed along the way,” says Fuqua. “It also influenced me quite a bit regarding the idea of war, slavery and the brutality surrounding it which is so crazy and inhumane. Even today, when you watch what’s happening in Ukraine, and other parts of the world, it doesn’t feel like it’s on the same planet.”

This idea formed part of the conversation when Fuqua examined tests Richardson and Legato shot in the swamp and soaring over the water – it felt alien. “If you were a slave and a black man, snatched from Africa and brought to another place, you would feel like an alien,” he adds. “Hollywood rarely deals with the slave’s perspective, the story’s normally from the slave owner’s perspective and almost peaceful. The situation was not at all peaceful – it was brutal and ugly and from a slave’s perspective, there wouldn’t be much colour in the world.”

As the filmmakers pieced together the look, rhythm and colour were key considerations. Richardson tweaked the visual approach and presented Fuqua with new options, the colour draining from the visuals each time they watched the test footage. “As Peter went on his journey, it got darker,” says the director. “The battle sequence during the Civil War later in the film is almost completely black-and-white, except for the red used in elements such as blood.”

What was happening to the character and their state of mind motivated where splashes of colour were added, and the filmmakers tracked Peter as his character developed – through yellow fever, mosquitoes, battles. “So, when we get to the scene of the burning house, it was completely surreal. Horses were galloping around and on fire, and the colour was fading away even more,” says Fuqua.

Richardson emphasised the importance of letting scenes breathe and minimising the number of cuts, shooting some sequences where he “just let the audience really experience what was happening and trusted their patience to let things be, and really be in the environment.”

As well as trusting in and avoiding dictating to the audience, the filmmakers had faith in each other while bringing the story to the screen.Richardson praises Fuqua for never losing sight of their vision to communicate the cruelty of the situation whilst also lensing elements of the hypnotically beautiful. “Antoine became my brother during the process, and we found a shorthand rapidly which we’ve taken onto another production we just wrapped,” says the cinematographer.

A spiritual element was also at play during filming, introduced by Smith and further nurtured by Fuqua. Smith’s powerful performance impacted camera movement as well as the overall tone of scenes. Richardson elaborates: “In one sequence Peter climbs into the swamp and the camera shoots up over the tree. When it comes back down Peter’s hands are up and then we cut to another shot and he’s right beside a tree in a different space. Those movements also motivated shifts in the tonalities of scenes – whether they were slightly cool, more blue, green, orange or red.”

Peter’s journey

Shooting took place in and around Louisiana, where the story is based, with Richardson heavily involved in the scouting process. Ahead of the crew arriving, he visited the potential locations to explore the settings and send photos to Fuqua. These images were used within mood boards and other influential visuals such as the work of painters Delacroix or Caravaggio were discussed, their brutality triggering further ideas.

“It wasn’t easy moving around the locations in Louisiana because we were often in a swamp and it was hard to know if you should turn left or right,” says Fuqua. “This made us think about someone like Peter on the run, looking this way and that, and just seeing branches, leaves and alligators. What way should he go?”

The filmmakers discussed Peter’s journey, the direction he was travelling, and where the sun was at each point before making the final selection of locations which included former slave plantations such as Ardoyne Plantation in Houma, Louisiana, and Evergreen Plantation in St. John the Baptist Parish. The film begins as Peter is torn from his loved ones and transported to a Confederate labour camp to build a deadly weaponised railroad. Confronted with brutality, and then buoyed by rumours that President Lincoln has ended slavery, Peter decides to make a break for it.

“We decided to shoot the railroad scenes first and then tried to film in order, so our fantastic production designer Naomi Shanahan had to find a location where all that could be built,” says Fuqua. Months before production, Shohan began constructing the elaborate railroad camp set where Peter and other enslaved men are building the tracks for a siege train mounted with explosive cannons headed for Port Hudson, where it could solidify the Union’s efforts to control the Mississippi River.

Smith commends the production designer for creating “one of the best designed, most accurate sets” he has been on which surrounded and immersed him as “all of the sounds and emotions were brought to life.” When lensing the railroad scenes Richardson took advantage of the wide-open, spatial freedom that Shohan’s 360-degree set allowed, using aerials and every variety of mobile camera. “You could travel and move anywhere you wanted with cranes or Steadicams, and that’s what we did,” he says.

Fuqua adds: “Shooting such scenes during the pandemic made it even more difficult partly due to crew sickness. We were also contending with the heat, so Apple brought ice vests on set for cast and crew and even had to shut us down for 40 minutes on occasions so everybody could escape the heat.”

Richardson did not aim to exaggerate the heat of the environment on screen, “blow things out, overexpose or sell heat. I just aimed to show the unjust system under which those men had to work – seen in the railroad scenes in particular.”

Shooting in the swamps presented new challenges as no Steadicam or tracks could be used and further obstacles were faced when a hurricane hit. As the locations had already been locked, they shot the swamps that had been destroyed by the hurricane. “They weren’t as lush or as beautiful as before but perhaps that made the visuals more authentic,” says Richardson. “That starkness is now part of the film, whereas what it was before might have been too elegant.”

Emancipation was without question the hardest film of Smith’s career. “It was searing hot, a hurricane tore down our sets, I was in the swamp every day,” he says. “But when you’re telling a true story like this, there’s a huge energy you get from the meaningful purpose of sharing an incredible human life with others.”

Difficulties were also encountered when accessing a location Peter travels to in a canoe before climbing into the base of one of the seven-foot-wide trees. “Production said no to using that location, but Antoine persevered, and the owner of the property helped shave a road to allow a lumber truck with a Technocrane on it through so we could access the location and capture sweeping camera movements,” says Richardson.

While Technocrane was deemed more suitable than drones for that sequence, drones were used elsewhere forscene setting shots, captured by specialists in the aerial field including Chad Daring and Kyle Bullington. The battlefield sequence, which some may assume was drone work, was captured using cable cam. “Cable cam was effective as it is virtually repeatable so, if needed, Rob Legato and the visual effects team could more easily aid the final image with the addition of more troops and explosions,” adds Richardson.

Clear vision

Camera movement was dexterous and meticulously planned to capture Peter on the run, from creeping shots through to fast paced sweeping motions. Richardson credits the success of that approach to Fuqua’s vision and direction: “When he sets the scene, the camera is responding to the actors and characters, so if they’re moving fast, so is the camera. The motion is also motivated by the characters’ words and emotions.

“When we shot the scene where Peter’s wife Dodienne [Charmaine Bingwa] wakes up, the camera spins down and into a medium close-up, we were in a real house, a real slave pen that didn’t move. We were working with this tiny crane to capture an elaborate move and the shot was hard to light. But when I watched that scene, I was so moved by it. From Fuqua’s direction through to Charmaine’s performance, the results were wonderful.”

These shots were made possible thanks to Richardson’s trusty crew including B camera and Steadicam operator David J Thompson, 1st AC Jimmy Ward, and key grip Herb Ault. “That’s principally the world we worked in, and then other crew members were on the edge for the running shots, and we had one of the best drivers ??name?? to enable us to capture the landscape shots.”

When shooting Peter fleeing, the crew ran across uneven terrain with no roads, but the Ultimate Arm used for the car crane work remained stable, allowing them to capture the action. “We’d always find ways to make the camera move in a creative way,” says Richardson. “We shot a lot of that material at 48 frames per second and then brought it back to 24. The shutter speed would alter but I actually liked the slight strobing we got on those foreground elements, so we kept that, and I believe it greatly enhances the scenes.”

Filming in such demanding situations and locations called for a tightly knit team, from the operators through to the stunt performers and special effects. “Just look at the bombs going off everywhere in the Civil War battle scene – we all really had to be in sync,” says Fuqua. “For that sequence the camera car which Bob travelled in to capture the action had to keep up with Will and the other actors in a safe way, swerving around trees. The actors were really running and jumping over those trees. And when Will enters the swamp, there were really alligators in there, but he didn’t even hesitate to get in.”

Tools required to capture the above-the-water scenes of Peter in the swamp included the 50-foot Technocrane on top of a four-wheel drive vehicle used by the lumber industry. “The advantage of this was it could go anywhere, and we could get as close as we needed. You could put it on a high slope, and it would level out to the flat surface we required,” adds Richardson.

While the above the water scenes in the swamp were shot on location, when capturing underwater sequences in the swamp, Legato devised a method to shoot them safely. “How do you get Will Smith into a space like that? The swamps are too dark and they’re dangerous, so Rob basically built an aquarium and shot it in front of his television to demonstrate to the producers that his concept of shooting in front of a screen would work,” says Richardson. After receiving approval from production, that scene was one of the last to be shot over three days on stage in Los Angeles in a large tank in front of an LED screen displaying images of what the background would have been above or below the surface of the swamp. A puppet alligator then attacked Smith or his stunt double during the more violent sequences.

Camera tests led Richardson to opt to go down the RED route, shooting on the Ranger Monstro, Komodo and capturing a few shots on the black-and-white Ranger Monstro Monochrome camera at 5000 ASA.“We were pushing the image so hard, especially as we were shooting at 8K,” says Richardson. “RED were highly supportive of us in every way possible, which makes a big difference.”

The black-and-white camera was primarily used to shoot a fireside conversation lit by flames. “When I said we were ready to shoot, Antoine replied, ‘What? I can’t even see the actors.’ That’s how great the camera is in low light,” continues the cinematographer. “And when we shot a test with Will in the lowest light level we’d worked with, he said, ‘You must have one hell of a camera because I can’t even see my hand.’”

Panavision’s Dan Sasaki strived to fulfil the needs of the demanding shoot by creating a version of the Primo V Series tailored to the production. “We were fortunate to work with him – he created flares for us, worked with open stops, and what they call the RRs which offer really fast lensing.”

The lenses’ contrast level was “perfectly suited to working with the RED camera” and in testing Richardson “loved the way they captured skin – there was a softness, something closer to vintage. Antoine and I extended what we did with Dan when filming The Equalizer 3, pushing the limits even further by creating a slew of lenses including some smaller zooms.”

A natural approach

In line with the ambition to tell the historical tale in a natural way, lighting fixtures were rarely used. Even the nighttime scenes were not heavily lit and were often cool in tonality. “The fireside sequence with Peter and slave hunter Jim Fassell (Ben Foster) is lit by flames, and as I shot the close-ups, I brought a bar of propane fire closer to them, to achieve a slightly heightened level,” says Richardson. “Even the shot in that sequence that moves all the way across to Jim using a 50-foot Techno with a remote head is lit by fire.”

He highlights one of the most significant challenges for cinematographers when working in such locations and conditions is accepting you will be in top light for the majority of the day. When beginning the shoot by filming scenes in the railroad camp, often the filmmakers would avoid cutting, even if on occasions “it would probably have made it easier to achieve good looking images, because you can move with the light more.”

Early on, Richardson informed Fuqua they “would not be working with great light in the selected locations as the sun is virtually overhead from 9am until 4pm. But something I learned in the past when shooting in brutal, ugly light is you’ve got to turn what you’re most opposed to into something you engage with and make your friend. We took on the brutality and shifts of the top light and utilised it without thinking. It was about Peter, and his interactions with those around him.”

While working in harsh conditions and telling a tale of such vast logistical and emotional scale, the filmmakers reached new limits of directorial and cinematographic creativity and commitment. They deployed innovative new and tried and tested tools and techniques, experimented with an inventive tonal palette, and intricately choreographed long shots while developing a close partnership along the way. “We would have the same thought about how to shoot something,” says Richardson. “Just as I’d think to myself, ‘Let’s shift to 96-frames-a-second for this take,’ I’d hear Antoine say it out loud. It was uncanny.”

This united approach to filmmaking allowed the pair to capture fast-paced scenes of Peter on the run through to the more still but equally powerful shots of Peter sitting for the photo which inspired the movie. Richardson emphasised the importance of creating the photograph using an authentic nineteenth century daguerreotype camera, producing an image on a sheet of copper plated with a thin coat of silver.

“The original photo is soft in a lot of areas but it’s sharp on the scars – and that can only come from using those particular cameras,” he says. “It was also vital to get the positioning right. It would have been very easy just to shoot it with our camera, but it wouldn’t have the same feeling. We needed to get the soul of it.”

Through the skill and passion for the production Smith and Richardson displayed in that scene, which marks an important moment of release at the end of the film, Fuqua believes they captured “not just the brutality of the image but the simplicity and uncomfortableness of this moment that led to a rallying cry against slavery.”

–

All images courtesy of Quantrell Colbert/Apple TV+