Top Gun

Rob Hardy BSC / Mission: Impossible - Fallout

Top Gun

Rob Hardy BSC / Mission: Impossible - Fallout

BY: Ron Prince

Your mission… Rob Hardy BSC… should you choose to accept it… is to spend the next year and a bit, shooting the most highly-anticipated action movie of 2018, starring Tom Cruise, who will perform nerve-jangling stunts himself, in remote, glamorous and seedy locations worldwide, and to capture the ensuing thrills and spills on 35mm film. Of course, Hardy said yes!

Mission: Impossible – Fallout, written, co-produced and directed by Christopher McQuarrie, is the sixth movie in the Paramount Pictures franchise, which has grossed more than $2.7 billion to date. McQuarrie is the first person to direct more than one film in the franchise, having helmed the fifth installment Mission: Impossible – Rogue Nation (2015, DP Robert Elswit ASC).

Although the budget for the latest production has not been disclosed, it is likely to be in the region of the $150million spent on the previous film, which returned a handsome $682million at the box office. In this episode, the world is faced with alarming consequences, after an Impossible Missions Force (IMF) operation ends far from well. Ethan Hunt (Tom Cruise) takes it upon himself to fulfill his original brief, but the CIA begins to suspect his loyalty and his motives. All of a sudden, Hunt finds himself in a race against time, hounded by assassins and former allies alike, whilst attempting to avert a global disaster.

Along with Cruise, the film stars Simon Pegg, Rebecca Ferguson, Ving Rhames, Sean Harris, Michelle Monaghan, and Alec Baldwin, who all reprise roles from previous films, with Henry Cavill and Angela Bassett joining the franchise.

Hardy’s credits include John Crowley’s Boy A (2007), Red Riding: The Year Of Our Lord 1974 (2009, dir. Julian Jarrold), Broken (2012, dir. Rufus Norris), The Invisible Woman (2013, dir. Ralph Feinnes) plus Ex Machina (2014) and Annihilation (2018), both directed by Alex Garland.

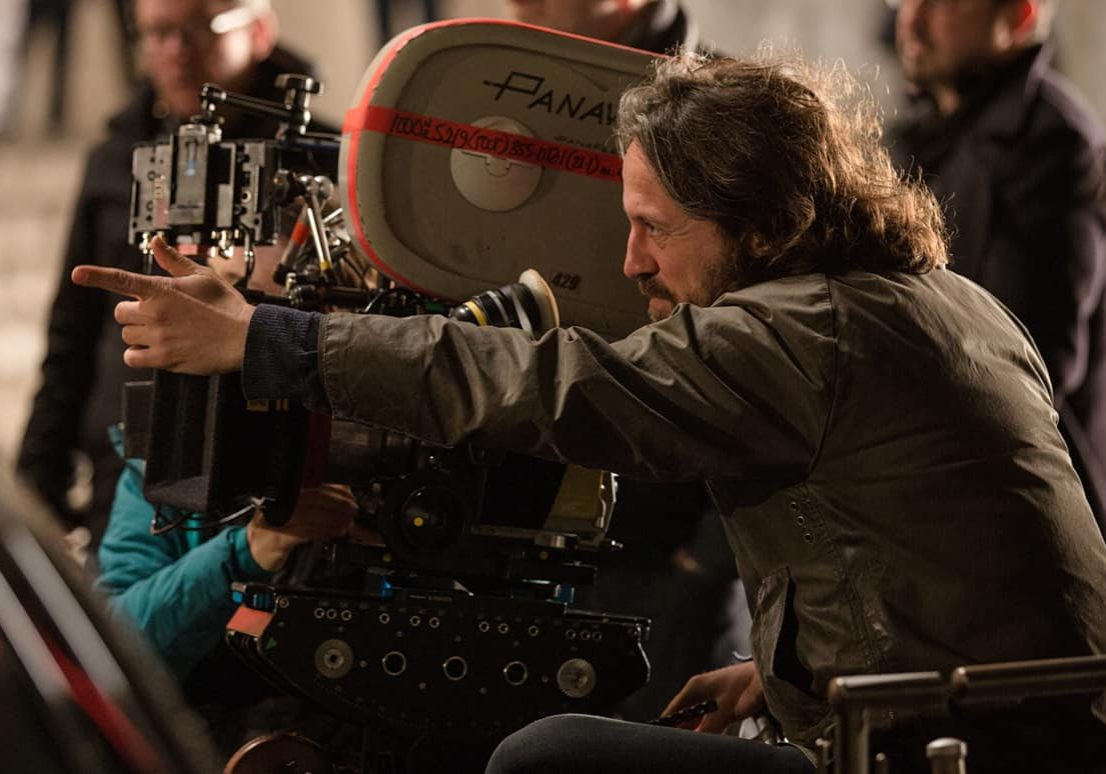

On a movie of this scale, it’s quite rare that the cinematographer also chooses to shoot A-camera themselves. But that’s exactly what Hardy did, preferring to be up-close and personal with the action. After a three-month prep period, filming on 35mm started in April 2017 in Paris, before moving to locations in Norway, New Zealand, India, and London, with production also encompassing sets built at Warner Bros. Studios Leavesden.

Towards the end of the New Zealand shoot, Hardy was granted a special dispensation to return to the UK, to be with his wife for the birth of their son Arthur. On the day of the birth, he received a video, featuring Cruise and the crew singing happy birthday!

In August 2017, Cruise badly injured his right ankle during a stunt routine in London, and production was halted for two months whilst the actor recuperated. Filming concluded in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) at the end of March 2018, where the plucky Cruise performed a High Altitude Low Opening (HALO) jump scene from a C-17 military transport aircraft.

Mission: Impossible – Fallout is scheduled to be released in 2D IMAX, RealD 3D and IMAX 3D, as well as standard theatrical release. Ron Prince caught up with Hardy, who was taking extended time out in LA with his young family, to discover more about the cinematographer’s work on the movie.

It must have been hugely exciting to be invited to shoot Mission: Impossible – Fallout. How did you come to get involved?

RH: Yes, it certainly was. There were a couple of other projects I was considering, similar to the types of films I had done before, but I got a request to speak with Chris McQuarrie. Mission was a completely different kind of challenge. In their search for a cinematographer, Chris, Tom and Jake Myers, one of the producers, went to the cutting room in Soho where Alex Garland was editing Annihilation. Tom and company sat with Alex, watched the cut and asked a lot of questions about my work. Tom’s specific obsession at that point concerned how dark I was prepared to go, which is my sort of territory. They liked what they saw, and two days later I got the call.

What was your initial brief for the film?

RH: Both Chris and Tom’s emphasis was on creating something quite different to previous films, something altogether darker and more sinister looking. Chris also wanted it to feel as if it had been directed by a completely different person to the previous movie. There was a desire to shoot everything as practically as possible, and to not spend too much time on greenscreens with an abundance of visual effects. Even though it had tremendous scale, there was something very practical about their approach – a back-to-basics, raw and energetic, French Connection style of filmmaking.

The prerequisite was to shoot on 35mm film, and meeting Chris and Tom was refreshing. Tom in particular, has such an appealing and infectious energy, that it makes you want to pull out the stops and do the best you can.

Did you consider any particular creative references, and did you watch the previous Mission: Impossible movies?

RH: I know the Mission: Impossible franchise movies pretty well, and went back to watch the first, fourth and fifth instalments. This was really to more fully-understand the character and narrative arcs, rather than for how the new movie would look. At the early stages for me it was all about listening, discussing and getting a sense of where the collective mindset was at.

Chris is a great cinephile, and we talked a lot about a range of different movies, particularly those stylish, naturalistic-looking thrillers from the 1970s, like Klute (1971) and All The President’s Men (1976) – both directed by dir. Alan J Pakula and shot by Gordon Willis ASC – for their emphasis on darkness and suspense, and their iconic, atmospheric and tense framing.

I also drew inspiration from other sources. For example, for one of the early sequences in the movie, that takes place during a huge party at the Grand Palais in Paris, I was reminded of the dazzling, sunlight effect in Olafur Eliasson's 2013 Weather Project in Tate Modern's Turbine Hall, and I thought it would create a unique atmosphere in our movie.

"One of the visual themes in the film is how Tom’s character is constantly forced down a road that he does not want to take. So we always tried to frame him around objects and structures that disappear into infinity, and the lighting plays an important part in that aesthetic."

- Rob Hardy BSC

How did you feel about the prospect of shooting Mission: Impossible – Fallout on 35mm film?

RH: It had been a while since I’d shot 35mm on a long form project, not since Broken (2012) and Invisible Woman (2013). It took a moment to re-adjust to shooting on film, and the practices it requires. But, I quickly rediscovered that it is much simpler and more reliable to shoot on celluloid, than on digital. It was wonderful to be back in the saddle, to look through a viewfinder and see the detail in the reaction between the lens and the light, to have that discipline that comes with capturing on film. Looking back, the experience was fantastic and film never let us down.

What cameras and lenses did you choose?

RH: I selected the Panavision Millennium XL as it’s a beautiful, lightweight and quiet 35mm studio camera that can convert easily into handheld or Steadicam modes. It also has versatile short and telescopic viewfinder options, which I knew would be helpful in view of all the stunts we’d be shooting. I also quite like the sort of ‘80s IBM computer colour of it, if that makes any sense.

As for the lenses, the choice is always about the look you want to achieve. I shot Ex Machina with Xtal Xpress lenses, and Annihilation with a combination of Panavision Primos and G-Series, as they delivered images that gave a distinct personality when combined with the different digital cameras I used on those productions.

This time, however, I wanted a more classic, softer look. Panavision’s C-series and E-series Anamorphics are much more gentle, and I knew that film would really accentuate their subtleties and aberrations. I would love to say I had these lenses specially tweaked and tuned, but I didn’t. I was happy with how they looked during our tests at Leavesden.

I was, however, acutely aware that the C-series, in particular, are precious commodities, and that we ran the risk of damaging or destroying some of them during the stunts scenes. So I used the E-series, and the odd spherical lens, as back-ups. Luckily nothing was broken. Honest.

Which focal length lenses did you prefer?

RH: I went purposely towards the wider end of the range, in order to get the camera really close to the action, and to make the image more immersive and dramatic. I felt that the sense of closeness was an important tool for us narratively. Our workhorse lenses were the 35mm, 40mm and 50mm, for their sense of proximity, although the 75mm and 100mm would sometimes come into play depending on the location and the set-up.

Chris and Tom ribbed me quite a bit about it during production. I think it’s the first time I’ve ever heard anyone string together an entire thread of jokes based on the continued use of wide lenses. Tom‘s other favourite joke would be to insist that I would personally shoot him flying the helicopters from inside the chopper, at 9,000 feet, handheld, with him in the pilot seat. He found that continuously amusing.

Which filmstocks did you choose, and why?

RH: For the majority of the exteriors I used Kodak Vision 3 50D (5203), as it handles the dynamics of light and shade extremely well, with a rich palette of colours. I knew we would have some long scenes, when the action moves from bright, sunlit streets into shadowy alleyways, with the angle of the sun constantly changing. The 50D gave me the latitude I needed for these shots, and delivered a level detail in the highlights and shadows that I have not yet seen in digital.

On seriously overcast days, when I thought it too much of a push to use the 50D, I used Kodak Vision 3 200T (5213), which I balanced for daylight at 125ASA. I shot all of the interiors and nighttime scenes using Kodak Vision 3 500T (5219), which I balanced for daylight at 320ASA. The 500T is a really versatile film stock. I love its colour saturation and the contrast, and the level of detail in the rich blacks is just wonderful.

Overall, the way the film captured the style in which I tend to light, soft yet directional, with a lean towards Tungsten, was simply sublime. More than that, it captured it as my eye sees it, without any manipulation.

"I will never forget discussing the Grand Palais sequence on my first official day of prep at Leavesden Studios. Tom burst into the room and asked me directly, "So, how are you going to light this, Rob?" At that moment everyone went quiet as they waited for my answer."

- Rob Hardy BSC

Although this was chiefly a 35mm film production, you shot some of the aerial footage digitally. Why was this?

RH: Part of the initial movie release schedule involves IMAX display of the aerial helicopter stunt scenes, which were shot in New Zealand, plus a skydiving sequence, when Tom jumps from a C17 at 20,000ft. Although we could have shot these perfectly well on film, the flight logistics of the aircraft and extended takes, meant is was not feasible to keep landing to reload.

So I selected the Panavision DXL camera for these scenes, which we shot at 8K. It was a bit of an experiment, as the DXL was new at the time, barely used by anyone, and we were going to really put it through its paces on that aerial work, in mid-winter. An ex-NASA engineer fixed hard mounts to the aircraft interiors and exteriors, along with beautiful lightweight camera housings. I needn’t have been concerned, as the DXL performed perfectly well.

Tell us more about your camerawork?

RH: The aim was to get really close to the action, plus Tom wanted to play out scenes, and for the results to not get too cutty. So the camera positions and movements were designed, as much as possible, around shooting action sequences as long takes.

Also, the movie has some long dialogue scenes, with multiple characters. So, on these occasions, we had several cameras that allowed us to cross shoot, and keep things up-to-speed on the schedule.

As I wanted a particular framing style, I typically operated A-camera, assisted by my longtime collaborator Jennie Paddon, on focus. B-camera/Steadicam was operated by the brilliant Marcus Pohlus, assisted by Adam Coles, with C-camera operated by Julian Morson, supported by Olly Driscol.

We wanted the rooftop chase scene, during which Tom jumps from one building to another, to feel like one shot. We rigged up a wirecam, with a mini Libra head, that could do a 360-degree turn, and follow him over the precipice. I operated the wheels, and we rehearsed it with the stunt team many times over. Tom performed it three times, sadly injuring his foot on the third occasion. But the result is amazing – disorienting and exhilarating at the same time.

How about your lighting?

RH: I got the opportunity to light the interior of St Paul’s Cathedral – which is extraordinary. (That was also the day my nine-month old son, Arthur, achieved his first ever set visit – so it was memorable for two very good reasons).

Overall, the goal was to keep the look of the movie dark and sinister, but natural. All of the lighting was Tungsten, which I sometimes balanced for daylight. On both location and stage work, I wanted to be able to adjust the lighting to create the sense of scale and depth in the image. So I tended to light the whole space, but have the ability to take out chunks of light to create shape. It was a combination of walls of light and integral lighting. Rarely was there ever a lamp on-set that wasn’t some sort of fixture or featured on-camera in some way.

My gaffer, Martin Smith, was brilliant. He had a lot on his plate. Due to the production schedules, we rarely had the chance to pre-light scenes together, but he stayed well on top of things, and that was a great support.

One of the visual themes in the film is how Tom’s character is constantly forced down a road that he does not want to take, as if he were heading down a tunnel. So we always tried to frame him around objects and structures that disappear into infinity, and the lighting plays an important part in that aesthetic.

Was it problematic when Tom broke his foot?

RH: Yes, of course, as it meant we had to stop production. But, one advantage of the hiatus was that everyone could gather their thoughts, look at the edit and see what could be improved. For me, it meant I could spend a bit of time at home with Arthur and his mum.

Is there a scene in the movie that you are especially proud of?

RH: I really like the scenes we shot in the Grand Palais, and the ensuing fight scene, which we shot later on-set at Leavesden. I will never forget discussing the Grand Palais sequence on my first official day of prep at Leavesden Studios. At that point I was essentially playing catch-up and listening-in to the conversation between Chris, Peter Wenham, the production designer, and Wade Eastwood, the stunt coordinator. Tom burst into the room, and engaged in the conversation too, and asked me directly, “So, how are you going to light this, Rob?” At that moment everyone went quiet as they waited for my answer.

From my point-of-view, the scene was a huge greenhouse, shot at twilight, with a big rave going on. My instinct told me it was about lighting the space from one source, which would have to be huge and integral to the environment. So I told Tom, I knew exactly how I was going to light it, in the same way and with the same intensity and atmosphere that I would light any given scene in the movie.

It would have to fit in with our visual manifesto, and it would not look like any rave you’d seen before on film. I thought about the other big spaces that had been lit in a way that I intended to do, and recalled Olafur Eliasson's Weather Project in the Tate Modern Turbine Hall.

So, we came up with a huge circular softlight, that was built in sections in London, and shipped to Paris. It took four days to construct it at the Grand Palais. But it was worth it, as the effect is unique and dramatic to those scenes.

As for the fight scene in the bathroom, I thought it would play well if we stripped away the mystery, and that this brutal encounter took place in a stark, white environment – contrasting to the Grand Palais beautifully. We shot that on-stage at Leavesden several months after shooting at the Grand Palais. I lit it from above with fluorescent tubes and diffusion panels above the actors. I think that really paid off, as it’s a really ferocious-looking scene, and one of my favourite sequences in the film.

Tell us a little about the DI?

RH: I did the DI grade with Asa Shoul, as I always do, from Molinare in London. We did a couple of passes on the movie during April in London, and then did the final grade remotely via private network, as I am in LA.

Did you get involved with the RealD 3D and IMAX 3D releases?

RH: No. I left those in Asa’s capable hands, as by that point I’d moved on to prepping the next Alex Garland project.

Ultimately, how big of a challenge was Mission: Impossible – Fallout for for you?

RH: When you take a helicopter ride every morning to the top of a remote Norwegian fjord, and arrive at large unit base, you know you’re involved in quite a number! But, you still have to find solutions to everyday cinematographic problems – such as a changing script, maintaining your look, keeping up with the shooting schedule. So whilst the scale might change, your creative challenges remain the same. Although some of the action sequences seemed insane, the result is brilliant, and I loved every minute of it.