Young Guns

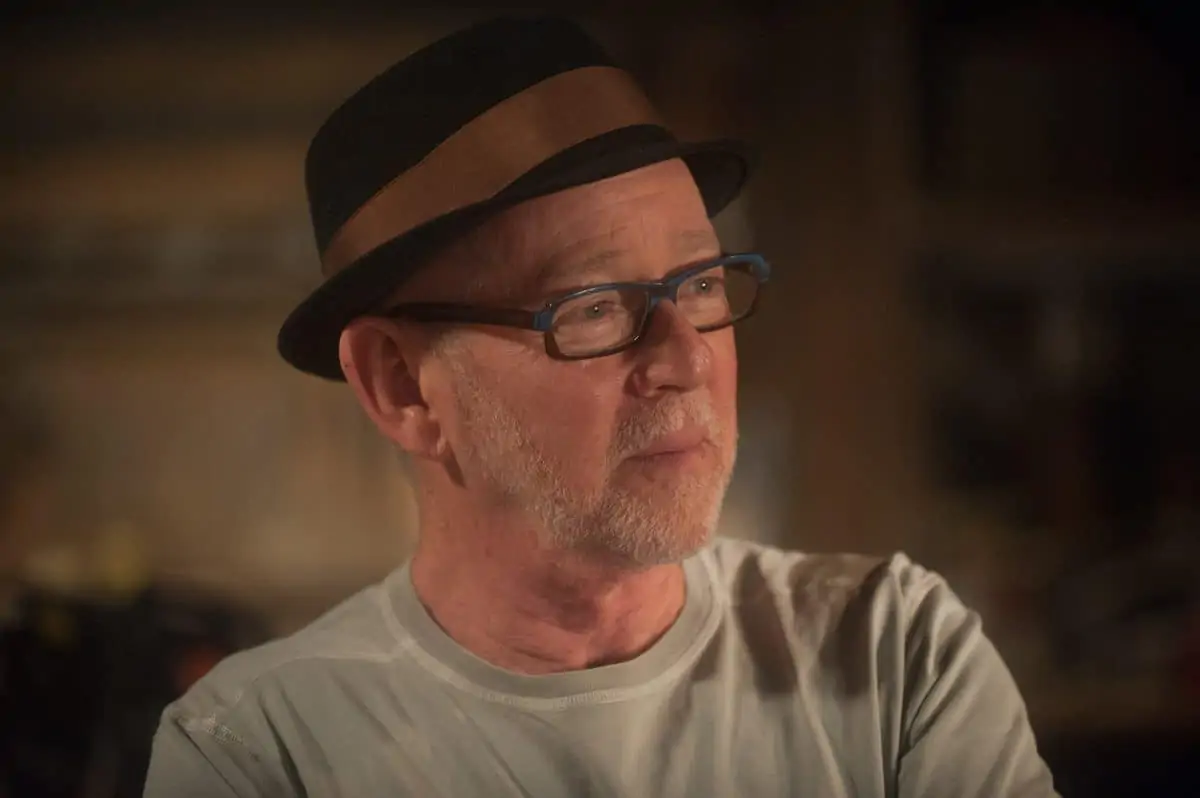

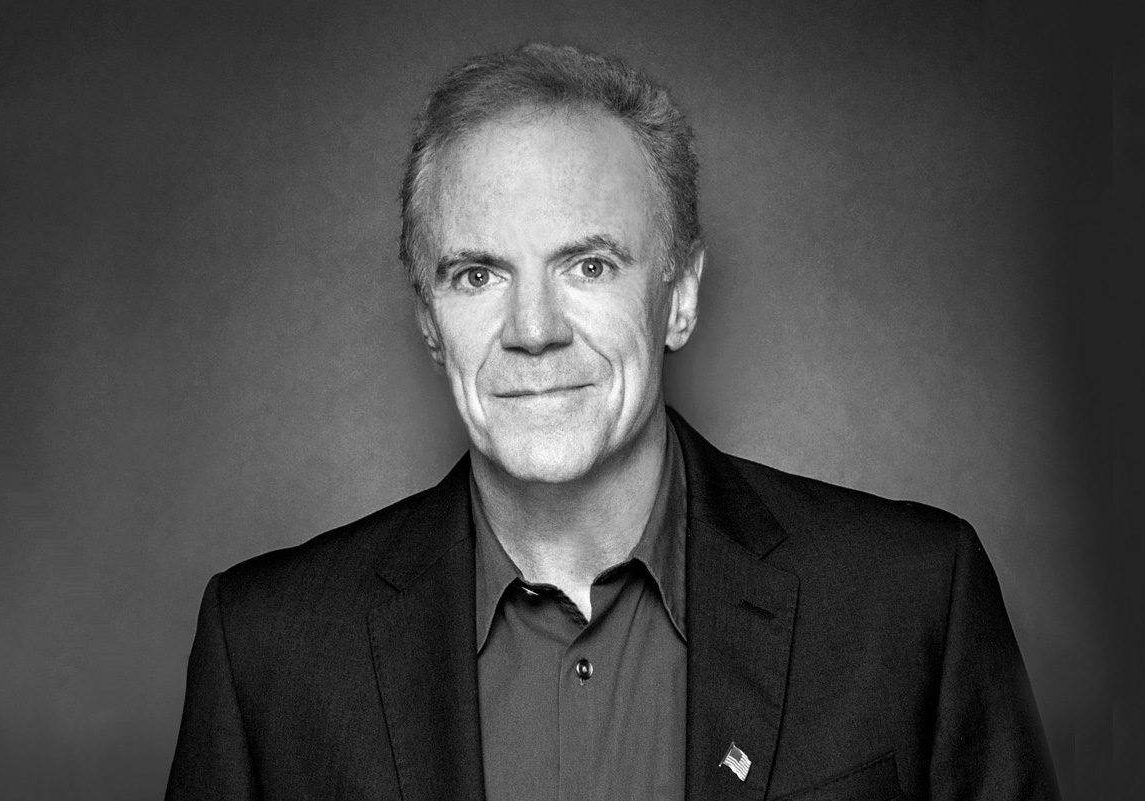

Letter From America / Richard Crudo ASC

Young Guns

Letter From America / Richard Crudo ASC

Richard Crudo ASC wonders how much the traditions of learning the art of filmmaking will affect the next generation.

I was speaking to a young student recently when a notion came to me, in the manner of a bus hitting you on the crosswalk. She had asked for advice on a variety of lighting and camera techniques and seemed sincere. So I gave her a good helping of the orthodoxy. But I soon found myself channelling the conversation in the direction of how a student should approach what we do. Commit yourself, become an observer of light, study hard, work even harder, make contacts, try to apprentice for someone who knows what they're doing, etc.

Then it struck me. My words weren't really getting through and she was starting to glaze over. As valid as any of my comments were, "None of it matters," I thought. "None of the old rules apply anymore."

Seeing as we're living in a post-truth era, indeed, in a world turned on its axis, this shouldn't have surprised me. It was also about the tenth time I had encountered this situation. The traditional ways of doing just about everything are finished. Why should we be immune? The system within which I and so many others were trained as technicians and nurtured as artists involved a slow, thorough process in which advancement didn't depend solely on ambition (though that was certainly there) or short-cutting the syllabus. It also turned on a willingness to absorb the traditions that came before us. That I, and many of my contemporaries, went about our pursuits with such dedication is still very admirable. That most of our youthful ethic seems to have been wiped out so quickly is...frightening.

I'm sure I sound like an old scold, but that's the furthest from what I am. This is not so much a critique as it is an observation filtered through my own experience. But I do think it holds a broader representation. In addition to spending the time to learn - really learn - what we were doing, such seemingly unrelated values as modesty and gratitude were being put into us as well.

I had the great good fortune to have worked as an assistant cameraman for a number of enormously talented cinematographers in the '80s and while some of them weren't especially forthcoming with their knowledge, there was always a lot to be gleaned just from the way they conducted themselves. Almost without exception they were admirable men, brilliantly talented and unflappable even in the most extraordinary of situations. I would liken the experience in many ways to working for your father or some highly-regarded professor, providing they were the type you respected. Although it doesn't bother me when I hear it, the idea of addressing one of them as 'dude' – as I have been hailed to by any number of up-and-comers – was rendered unthinkable through the often regal example they set. So maybe the world needed to loosen up a bit; we're clearly enjoying the benefit of that now. But even through the most staid aspects of my formative experience I was never uncomfortable or aware of anything unusual about the self-policing behaviour.

"The new order dictates that if this student wants to be a cinematographer she certainly doesn't need anyone's approval. She just declares herself as such and for all intents becomes one."

- Richard Crudo ASC

Another troubling thing is the presumptuous nature behind so much of what's happening lately. Witness the business card that young student handed me when we met. In addition to her name and contact information, it also listed her job qualifications – producer, writer, director, cinematographer, editor. Making claims to any one of those positions at that embryonic stage – however wishful and however confident – would've been unimaginable to beginners of an earlier generation. In the same sense that a cab driver doesn't advertise as an airline pilot, it would never have occurred to any of us to come across as so entitled. Was she merely a genius without resume? Not in the least. Maybe that perception is due to my common sense approach; I've always believed that you can't bargain with the truth. In that student's favour though, at least she didn't put 'cinematographer' last.

To prove I'm not really a dinosaur, there's a positive side to this story and it concerns the bracing vitality and boldness of youth. The audacity behind what was printed on that business card indicates something we all identify with from our early time on the job, no matter how or where we started – the energy, the optimism, the just-go-for-it mentality that made getting up every day exciting (it still is, by the way!). The new order dictates that if this student wants to be a cinematographer she certainly doesn't need anyone's approval. She just declares herself as such and for all intents becomes one.

Changes in technology and standards of acceptability have played a big part in making this possible, yet none of that matters anymore than do the strenuous lengths I had to go to in order to assemble a demo reel on film back in the day. As has always been the case, the only thing that counts is what ends up on the screen. How it gets there – in fact, who puts it there – is of no concern to most audiences.

Where are we heading then? That's anyone's guess. What will really be interesting is seeing how the kids carry the torch. With so much of the drudgery removed from the practice of cinematography, hopefully they'll find new and exciting ways of thinking about and approaching what we do – ways that the old system prevented my colleagues and I from even considering.

And who knows? Maybe they'll stop referring to the boss as 'dude.'