Cinematographer Owen Cant reflects on crafting a sense of chaos in a seemingly everyday setting in NFTS graduate film Trouble.

Trouble explores the intricate dynamics between two brothers in their early 20s, as they attempt to navigate their divorced parents’ shortcomings when Mum shows up uninvited to Dad’s birthday.

British Cinematographer (BC): Why did you decide to study cinematography? Please tell us a little bit about your filmmaking journey so far, as well as your influences and inspirations.

Owen Cant (OC): Why cinematography? I used to shoot my mates’ parties and holidays on a MiniDV camera in my early teens, edit them together on iMovie and attempt to sell them on DVDs in the high school playground. I enjoyed the freedom of creative expression from doing that and after a while I clocked onto the fact that I might actually be able to turn the passion for all this into a career.

I suppose cinematography chose me because I am a team player, keen collaborator and have always been a visual person in terms of the way I understand the world and express myself. I find studying the way light and contrast shape our understanding of the world an immensely satisfying process. The fulfilment I get from cinematography is unparalleled for me and the knowledge that every person on a film project has a unique role to play in making them happen, I find incredibly rewarding.

I originally studied editing, and took a lot from that process in terms of how to tell stories visually in an effective way. But after realising I can’t spend all day inside behind a screen, I was encouraged towards cinematography after my undergraduate BA tutor at Manchester Film School and former assistant camera, Gareth Hall, took me into Panavision one day. From that point forwards I was hooked on cinematography and shot as much as I physically could.

From 2013 onwards I worked as an assistant in the camera departments of HETV drama, commercial and film projects in the North West and around the UK, whilst simultaneously nurturing my creativity by shooting projects alongside my assisting career. Those eight years spent on set were incredibly valuable to me in terms of shaping my understanding of the industry, its people and what I could learn from some of the very best in the game. That experience gave me useful insights into cinematographic techniques as well as the character qualities of a good DP, with pragmatism, delegation skills, diplomacy and determination being key. I consistently draw on that knowledge now as a cinematographer.

I used to watch films such as Requiem of a dream, Run Lola Run and La Haine on repeat in my early teens. I was obsessed with how cinematography has the unique ability to put you in the experience of a film’s characters, and am even more so now. So I would say I am most influenced by films that are expressionistic in style, whilst also having something important to say about the wider world we live in.

BC: What were your initial discussions with director Sarah Blok about the visual approach for your film? What look and mood were you trying to achieve?

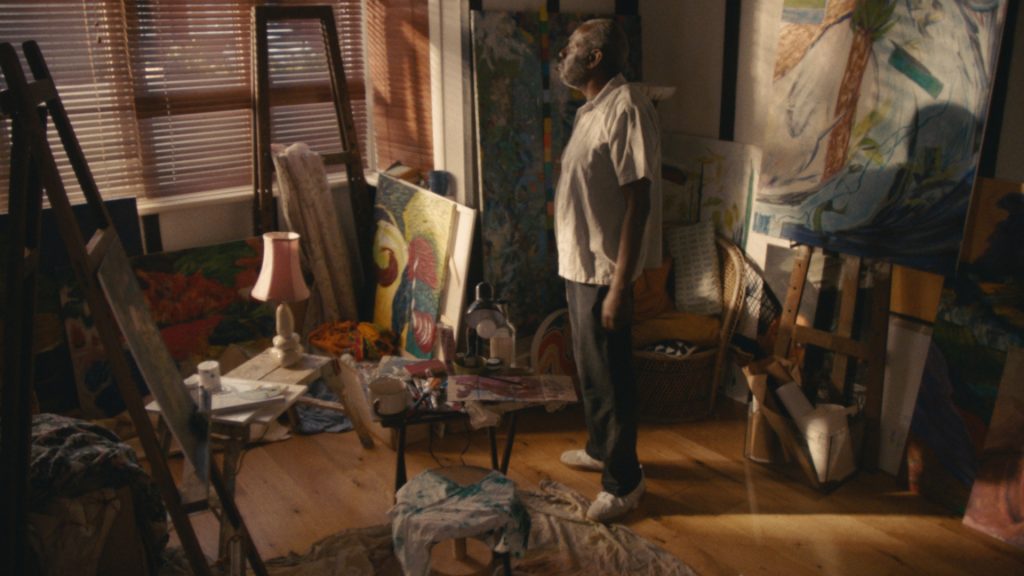

OC: On Trouble, a key part of our approach was creating a sense of chaos in an otherwise seemingly ‘everyday’, ‘slice of life’ setting. It was about translating this sense of tension, tarnished memories and evoking a sense of what could have been but also hope for what the future could bring.

It was important for us to find a language that highlights how complex family dynamics can be whilst retaining a sense of the everyday. We wanted to make it feel as though we just landed in this setting that seems relatively straightforward on the surface, but beneath that there are much more complex emotions at play. So making us feel those tensions between characters whilst leaning towards a more ‘real’ and naturalistic look was key for us.

BC: What were your creative references and inspirations for your film? Which films, still photography or paintings were you influenced by?

OC: A key influence for us was the John Cassavetes film A Woman Under the Influence (1974). It is a unique film that really puts you in the headspace of its central character, yet keeps a natural feeling look that subtly changes as the narrative progresses. The way in which long lenses are used to create a chaotic tension to seemingly ‘everyday’ scenes is something that inspired our visual approach. Powerful close ups were important to us in examining intimacy and connection and we referenced the documentary Some Kind of Heaven (dir. Lance Oppenheim, 2020) in terms of how it uses close-ups of people in their natural environments, yet reveals a deeper, more complex state of mind underneath.

Sarah and I both have documentary experience, so it was crucial for us that the actors to feel free to improvise and adapt in the shooting locations. Our approach was guided by a naturalistic and reactive style, staying within the visual language we had previously discussed and ensuring authentic performances were prioritised.

BC: What filming locations were used? Were any sets constructed?

OC: We shot the majority of the film in a house in North London which was more complex to find that you would imagine. It was key that the location really felt like it belonged to our characters, so somewhere large enough yet with distinct character and a sense of family history to it was important. Not easy to find on a limited budget!

We also shot on the London Underground with a MiniDV camera which was immensely fun and took me back to when I started out making films in my teens.

BC: What camera and lenses did you choose and why? What made them suitable for this production and the look you were trying to achieve?

OC: I shot the film on an ARRI Alexa Mini, using a PVintage 20-100mm T3.1 zoom (which is effectively a rehoused Cooke Varotal zoom). This zoom enabled us to evoke that classic ‘70s vintage softness and texture that felt right for our story.

We used Panavision Ultra Speed Primes on setups in the 100-150mm focal range which were a great match to the zoom. I also used an SFX1 filter the whole time to further soften the image and give a gradual rolloff to the highlights.

To go even further in creating a softer look, we shot 2K Prores 4444, which from testing felt like a better place to start from in terms of getting to a final 16mm vintage look than anything higher-res.

We also shot with a tiny Sony miniDV camera, to immerse our audience in the characters’ shared past and establish a tangible contrast to their present state during the summer evening depicted in the film.

BC: What was your general approach to lighting?

OC: The whole of Trouble is set over a short period set on a midsummer’s evening. So you could say it was one continuous scene in terms of the feel of the lighting.

What was important to me was creating a natural warmth of low sun. Somehow there is a feeling to that kind of light that makes me feel grounded and reflect on the past. So capturing that tone whilst creating an unrestrictive space for the cast to feel at home in was key to the lighting approach.

BC: What was the trickiest scene to light?

OC: Our whole film is set over a roughly 45-minute period, so was almost real-time in terms of the feeling of natural light. What was tricky was to maintain the feel of summer’s evening light throughout the film, whilst shooting over eight days and a variety of different weather conditions so typical of the UK. To work around this, I made sure the schedule was built around the weather conditions that week, so we mainly shot interiors on days where we were at risk of there being rain, and worked around where the sun would be coming from in relation to exterior scenes so that there was a consistent feeling of low sun throughout.

On exteriors we used a gelled M40 through diffusion to create shape, and diffusion and neg fill where necessary. On interiors I mainly used practical lights whilst making use of the M40 as a key coming in through the windows.

Massive shoutout to my gaffer Sam Hilaire, who did an incredible job along with our excellent team of sparks, without whom it would’ve been impossible to maintain that look. Sam was always able to offer up solutions to any challenges we came up against which is what I look for in all members of my lighting and camera teams.

BC: Who did the grade and what look did you want to achieve?

OC: Maintaining the low-sun feel throughout all the scenes shot on eight different days was quite a challenge, so our grading process was very important it balancing everything out. Emmanuel Benjamin our colourist, did a fantastic job in this regard.

Sarah, the director, and I aimed for a 16mm, heavier grain aesthetic from our initial project discussions during prep. We felt a softer, textured look best expressed the dynamic between the family members in our story. Emmanuel did a great job of applying film emulation in a dynamic way relative to the highlights and shadows in each scene and I’m really happy with the result.

BC: What is your proudest moment from the production process?

OC: The collaboration with my director, Sarah Blok, was a fantastic process. Right from the start, we both recognised that prioritising performance was essential throughout the entire film. So lighting and shooting in a way which allowed cast the freedom to feel they really were the characters they were playing in the location they were in was hugely important to us both. Creating that shorthand with a director, where you are on each other’s wavelength and know before taking your eye from the eyepiece, that you’ve got the scene was the best part of the process for me.

BC: What lessons did you learn from this production that you’ll take with you onto future productions?

OC: I have a solid understanding now of how important scheduling is when working with natural light, and what it’s like to be that DP saying when we can go or not when the biggest key light on earth is in and out of clouds. So making sure I’ve done everything I can in prep to ensure the schedule is on my side is something I will definitely take with me into the future, whilst always having a backup plan to be able to adapt when necessary.

I thoroughly enjoyed shooting at the longer end of the focal range, more than I had ever done before, and so this was a valuable lesson to me in terms of how to use longer lenses to evoke intimacy and connection between characters.

BC: What would be your dream project as a cinematographer?

OC: In the future, I want to dive into creating films that capture real-life experiences and explore ideas that push against the norm, that have the ability to bring a captivating and meaningful perspective on societal issues. However, what matters most to me is establishing trust with directors, creating a space for visual creativity, and adapting the visual language to suit the themes and the director’s vision for each story. Being in that symbiotic space where you are already on the same wavelength, yet able to challenge each other’s opinions is where I want to be. But to answer the question, I’d love to shoot a film with as much political insight and influence on its generation as La Haine did on mine.

BC: Is there anyone not yet mentioned that you’d like to highlight?

OC: Yaz Evans our 1st AD did a fantastic job of keeping us on track, our spirits high and worked with me to make sure the feel of the light was an important factor to the schedule. Davide Azzalini also did an amazing job on focus with the many tricky long lens shots and was an all-round professional on set.

Read the rest of our series spotlighting the NFTS’ 2024 cinematography cohort.