ON A MISSION

The filmmaking maestros behind sci-fi epic The Midnight Sky shot in snowstorms, created photorealistic virtual environments, and seamlessly blended stellar visual effects with stunning cinematography to tell a tale of two disparate environments.

When the opportunity arose to explore two worlds – the Arctic and space – while lensing apocalyptic space drama The Midnight Sky, cinematographer Martin Ruhe ASC was thrilled to accept the ambitious mission.

“We see these environments quite often in film, but rarely in one production,” Ruhe says. “It was a joy to cover such large canvases and epic ground, but through an intimate story.”

The film marks the second director-DP collaboration between George Clooney and Ruhe, who teamed up for mini-series Catch-22 (2019). “There was something exciting about the premise of The Midnight Sky which, as George describes it, is like Gravity meets The Revenant. Both films provided inspiration early on as well as stills from Russian photographer Evgenia Arbugaeva,” says Ruhe.

In what is fundamentally a story of hope as well as a warning of the damage humans are inflicting on the planet, Augustine Lofthouse (George Clooney), a terminally ill scientist living in isolation in the Arctic, battles to contact astronauts on a return mission exploring Jupiter moon K23. They are unaware of the global catastrophe awaiting them on Earth. As Augustine endeavours to warn Sully (Felicity Jones) and the crew of the deadly radiation destroying the planet, he encounters Iris (Caoilinn Springall), a young girl he must also protect from the elements.

Having starred in other space epics such as Gravity (2013) and Solaris (2002), Clooney brought with him knowledge of the techniques that could help create The Midnight Sky’s intergalactic scenesand an appreciation of the complexities of zero-gravity work.

“We didn’t have the year or more of prep time Gravity had, so we simplified the process,” says Ruhe. “We also wanted our version of space to have a grain to it and to feel older than some space films which look so pristine.”

Camera and lens choice helped realise these aesthetic ambitions. Clooney suggested shooting 65mm digital early on, partly because the film, which streamed on Netflix and at the time of writing was set to become one of the streaming service’s most-watched films, was originally intended as a cinema release and possibly an IMAX production. As Ruhe had not yet shot 65mm digital, he and Clooney carried out camera tests before committing to the format.

“We liked the results when testing the ARRI Alexa 65 and Prime lenses because the field of view is quite unique – you have to get closer to the actors and their faces. It worked well for the landscapes and some of the space work due to the detail and richness.”

For select scenes Ruhe paired the Alexa 65 large-format camera with custom designed detuned ARRI Prime DNA LF lens prototypes he was introduced to by ARRI Rental. “They create an effect where the image gets darker at the edges and loses focus. It can be tough for focus pullers, but it’s so beautiful,” he says. “This was useful for scenes in which we needed to get inside the characters’ heads and fade out everything around them, such as during the spacewalk when astronaut Maya spots the first blood drops in her helmet and realises she is hurt.”

Battling against the elements

The tale of two worlds demanded an assortment of diverse shooting locations. Iceland provided the stark, harsh setting for exterior Arctic scenes while the Barbeau Research Station where Augustine discovers young Iris, spaceship interiors and a night-time sequence in which Augustine and Iris sink under water were filmed at Shepperton Studios. Flashback sequences and those taking place on the moon of K23 were filmed in La Palma in the Canary Islands, Spain, where the gigantic Gran Telescopio Canarias optical telescope is located.

The 10-week prep period commenced in June 2019, during which time production designer Jim Bissell travelled to Iceland and Spain multiple times to scope out potential shooting locations before presenting ideas. Ruhe then visited the locations in July before shooting began in Iceland in October 2019, ending in La Palma in February 2020, just prior to the pandemic.

The crew and cast battled against extreme conditions in Iceland, filming some sequences in a real snowstorm for authenticity. “It was an amazing experience but totally exhausting for the crew, and even more so for the actors. Ice even formed on George’s eyebrows,” says Ruhe.

Although most of the snowstorm sequence was shot in Iceland, the final part was filmed on a stage in Shepperton. “If we hadn’t experienced it first-hand, I think we would have filmed it much softer and less violent on the stage, but we knew it was really brutal,” he adds.

Each day the crew drove for an hour from the hotel to base camp 1,000 metres above sea level, where equipment was loaded into mini vans designed to withstand the rough terrain of the glacier, equipped with heavy-duty tyres to avoid sinking into the ice.

“You could set off in good visibility and three minutes later the car bumper 10 feet ahead wasn’t visible,” says Ruhe. “We had to be flexible and react quickly, but simple things such as changing the lens took 20 minutes because you had to take the camera into the mini van to unpack it.”

In addition to Prime and detuned DNA lenses, Ruhe took a selection of ARRIzoom lenses to Iceland for flexibility. Exterior Arctic scenes were shot with two 65mm cameras, using Steadicam when possible and switching to hand-held when the wind was too strong.

“We used a Dolly a few times and a Technocrane once because it was a logistical challenge just to get it up on to the glacier,” he adds. “We thought about lighting on the glacier, but quickly gave up on that idea because the conditions limited us so we couldn’t just put up a light.”

Aerial shots of the Icelandic landscape were captured by OZZO, drone operators from Reykjavik, Iceland, whose footage, particularly of the Northern Lights, had impressed Ruhe. “It was breathtakingly beautiful. He also knew all the areas we wanted to film and was used to the extreme conditions.”

Ruhe wanted to avoid the tone often adopted when filming snowy scenes. “We experimented with a version that was really cold and blue, but it just didn’t work. We didn’t want to superimpose a look that was a cliché. And then, when we shot whilst the sun was out, it looked beautiful and dangerous simultaneously, even with a warmer tone.”

Intuitive camera movement was used during the glacier shoot, driven partly by the circumstances and the speed shots needed to be captured. “Once we were in Iceland we wanted to shoot as much as possible within the limited hours of daylight. We were also working with a seven-year-old actress [Caoilinn Springall] who we needed to protect, so we wanted to avoid spending more time than necessary in conditions that could be exhausting and dangerous,” says Ruhe.

Another dimension

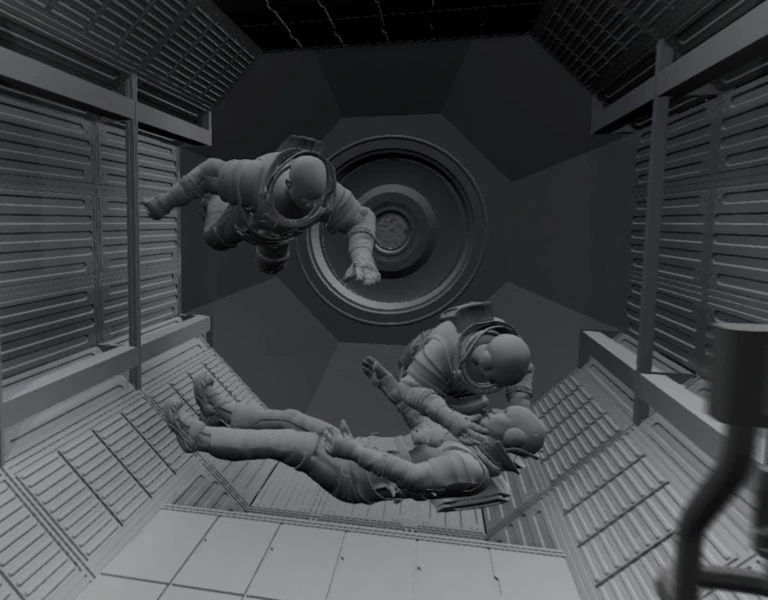

A different approach to camera movement was adopted for scenes in space. “When the astronauts embark on a spacewalk, there’s no centre of gravity. When they float, there would naturally always be some people who are upside down. This was something George mentioned from the beginning and that we wanted to achieve. We looked to the spacewalk in Gravity for inspiration because there’s never a straight shot,” explains Ruhe.

The DP did not want to use cranes too heavily for space scenes due to the number of people required to move the camera into position. “We needed to be more intimate, so we tried to film a lot with Steadicam and Alexa Mini LFs, with operator Karsten Jacobsen walking around actors and reacting to the moment. We also went handheld for certain space scenes such as in the airlock or when the asteroids hit the spaceship; it was intuitive and felt like a natural choice.”

When exploring the available options for capturing the spacewalk shots using Steadicam, Jacobsen discovered a device that allowed the camera to be rotated around the optical axis – the Rock-a-bye true horizon system. “In one shot the camera travels along the spaceship – the first time Maya goes into space and is nervous about it. We move around her head and then see what she sees before returning to her. Using Steadicam and the rotation system makes the audience lose their sense of gravity in the moment,” explains Ruhe.

The talented camera crew working alongside Jacobsen included A cam 1st AC Julian Bucknall; A cam 2nd AC Alex Collings; B cam 1st AC Lewis Hume; B cam 2nd AC Archie Muller; central loader Dan Glazebrook; and trainee: Freddie FitzHerbert.

We wanted our version of space to have a grain to it and to feel older than some space films which look so pristine.

Martin Ruhe ASC

Seeing into space

Matt Kasmir, The Midnight Sky’s visual effects supervisor, and the visual effects team at Framestore introduced Ruhe to a virtual camera system to previsualise scenes and walk around the spaceship set to determine which elements should be repositioned.

“Production designer Jim Bissell had already conducted so much research and was talking to NASA to decide how to develop the space world, but the virtual system gave us a good sense of the environments. Tape marks were made on the floor in scale with the spaceship and then I walked around the 3D spaces and collected shots on an iPad to show George. Editor Stephen Mirrione then edited them together so we could work out where additional shots might be needed.”

Moving the camera in space allowed the team to decide which moments would be best captured using crane shots, Steadicam or handheld. The data from the virtual camera system also informed the programming of the wires for the zero-gravity scene wire work. “The stunt people could then begin rehearsing and training the actors, apart from Felicity Jones who was pregnant and never on a wire,” says Ruhe.

In parallel, pre-production supervisor Kaya Jabar used the art department’s CAD model for the Barbeau set to plan for the LED work. The VFX team shot camera tests with the camera and lens package to monitor aliasing and moiré effects and built it into a simulation that could be walked around with an iPad to explore the set and highlight any screens that would need images replacing in post.

“This helped everyone understand the scope of work as well as being a reassuring preview of what the technology would ultimately bring to the shots,” says Chris Lawrence, VFX supervisor, Framestore.

As well as guiding the previs for key production challenges such as the spacewalk and the LEDs for the windows of the Barbeau Research Station interiors, Framestore helped Jim Bissell’s team realise the design of the Aether spacecraft. VFX art director Jonathan Openhaffen worked on materials and finish and collaborated with the previs team to support the staging of the spacewalk as the blocking evolved.

When the spaceship design was being refined and colour palette decisions were yet to be finalised, LED technology lent a helping hand. Thousands of metres of RGBW LED ribbon and pads were installed inside the spaceship set at Shepperton, comprising several kits of Astera Helios and Titans and Kino Flo FreeStyle 31 in all the sets and around camera. The ability to change their colour easily gave Ruhe and the lighting team extra flexibility as they explored how best to illuminate the private quarters where the astronauts experience personal memories. “Access was also limited in the spaceship set, so the fixtures and LED strips we chose to achieve these effects had to be very small,” says Ruhe. “As we experimented, we felt warmer tones best suited the personal pods, whereas the command areas would be colder.”

Other techniques were introduced to simulate backgrounds with interactive and perfectly matching lighting in night and day scenes such as an Arctic night-time sequence in the pod where Augustine and Iris take shelter. Gaffer Julian White suggested using a large 280’ by 40’ grey Rosco rear projection screen, but instead of projecting an image behind the screen, it was illuminated by a large array of ARRI SkyPanels which blended into an extensive soft light. All lighting equipment was supplied by MBSE.

“Using this method, we could dial in the colour from a still or video of a sunset or the Northern Lights, for example. In a snowstorm the white would constantly change due to the sun, which we could alter with the rear projection screen set-up, using around 500 Sky Panels that we could make any colour we liked,” says Ruhe.

“We added a diffuse sun by placing a Sumolight Super 7 right behind the screen,” adds White. “As it was on electric hoists, we could raise and lower it quickly to place a sun in the back of shot for the blizzard scene. An 18kw ARRIMAX with 1/4 CTS on a scissor lift was used for a harder sun and the studio ceiling was rigged with SkyPanels through grid cloth.”

Opting for this technique over blue or green screen helped immerse the cast and crew in the shots and avoided losing some colour information. It also enhanced the realism of the final comps created at Framestore because the complexity of the lighting was reflected in the snow on the studio set. “It saved a lot of money as VFX had less to do in post and we could also use smoke and snow effects without causing problems in post,” says White.

Photo realistic magic

The production leveraged Industrial Light & Magic’s effects experience by deploying the company’s StageCraft integrated virtual production platform. The system, which was also used to great effect on Disney+ sci-fi series The Mandalorian created three-dimensional realistic backgrounds surrounding the sets at Shepperton Studios using LED screens made up of more than 1,400 ROE Visual Black Pearl 2.8mm panels supplied by VSS, using Brompton Tessera SX40 processors.

ILM chose to work with VSS following collaborations including Star Wars: The Rise of Skywalker and the Peacock sci-fi series, Brave New World. The company was involved early in the design process, testing with ILM in the lead-up to the build at Shepperton, and consulting on screen types to be used in-camera for the main walls and lighting panels.

Aside from the 1,400 Black Pearl 2.8mm modules in the 30ft by 130ft and 50ft by 50ft screens, VSS also supplied 264 panels of ROE BO3 3.47mm for lighting panels. During the shoot, VSS was on hand to advise on removing panels to accommodate new camera positions, switch feeds to the screens and make any required colour corrections.

Six weeks before principal photography began, visual effects supervisor Matt Kasmir shot plates using an Alexa 65 three-camera array for selected scenes’ virtual backgrounds. ILM produced several digital layers to add to the projected environment including levels of atmosphere, falling snow and an Aurora Borealis effect.

“These were projected over 3D geometry before principal photography started. We 3D mapped the environment we would project our camera array onto using a lidar system and photogrammetry. A lot of visual effects work began during prep which meant we could get 100 to 200 shots in camera before we hit post,” explains Kasmir.

The set was quite reflective and featured huge panoramic windows. Kasmir and the team knew the LED StageCraft system would be best suited as it made the world outside the windows in the space control room, or the Barbeau Research Station, look realistic for scenes including when Augustine looks out the window while drinking an early morning coffee. “ILM’s system was the best I’d seen. It had in-camera parallax, meaning the screen position and angle change depending on where the camera is looking to give genuine in-camera movement,” says Kasmir.

“If we’d used green screen it would have caused a lot of reflections on the large windows in some scenes,” adds Ruhe. “If you take those out, you need to replace them with other reflections. Using ILM’s system the actors could look out at a realistic Arctic scene because the reflection on the window is a real reflection projected from an LED screen.”

Gaming engine Unreal Engine 4 was vital, permitting manipulation of the 3D environment in real time and camera tracking using mocap technology throughout the set. “The geometry of the area from the plates shot in Iceland was taken into Unreal Engine and projected and then the images were stitched together from the 365-degree footage and projected onto the geometry,” says Kasmir.

“We could rotate and move that around, create snow flurries, change the sky, so it became a fully functioning 3D environment within the gaming engine. Unreal Engine knew where our camera was and what lenses were on our cameras so the LED’s curved surface area could be adjusted accordingly.”

I love the spacewalk and Maya’s story that unfolds in that moment. It’s such a powerful combination of CGI when everything comes together because we collaborated to design the shots.

Martin Ruhe ASC

Realising the vision

Although filming concluded just ahead of the pandemic, the coronavirus restrictions impacted The Midnight Sky’s already tight post-production schedule, forcing grading to be carried out remotely. When COVID restrictions permitted, Ruhe viewed the film on a cinema screen in Company 3’s London location, while Company 3 co-founder and colourist, Stefan Sonnenfeld, Clooney and producer Grant Heslov worked remotely in LA.

“It was great that they wanted me so heavily involved in this stage of the process which saw us collaborate for two weeks of remote grading sessions,” says Ruhe. “As impressive as the technology that allowed us to do this is, working remotely just isn’t the same as being in the same room and discussing more immediately.”

To help realise scenes that could not be created in camera, visual effects supervisor Matt Kasmir and executive producer Greg Baxter sourced a stellar selection of visual effects specialists. Framestore played a pivotal role in the zero-G work and exterior space VFX shots and most of the CGI Arctic environments, delivering over 450 of the film’s 600 VFX shots and drawing on valuable experience gained whilst working on Gravity.

The team was involved from the outset, helping explore production methodologies and planning for the use of ILM’s vendor services such as StageCraft for the LED environments and Anyma for facial capture. “We wanted to give Martin as much control and input as possible, presenting technology as a tool to enable him to realise his vision as a cinematographer and making sure it didn’t become something that was so complicated it got in the way,” says Chris Lawrence, VFX supervisor for Framestore.

Framestore delivered digital face replacements which were initially required due to travel and availability restrictions. They shot plates for the close-ups of actors’ faces and combined them with a subtle zero-G body performance, courtesy of animation supervisor Max Solomon, who Lawrence collaborated with on Gravity. “The tests were so promising that we pursued this for all characters in the spacewalk scene, meaning our shot creation was less constrained by the practical limitations of shooting on wires with revolving sets,” adds Lawrence.

Wider shots combined innovative techniques with facial capture. Head direction and eye direction were manipulated to ensure eyelines were accurate, but every other facet of the actors’ performance were as they performed it during the capture shoot, resulting in subtle, invisible visual effects work.

In one interior zero-G scene, Clooney wanted a continuous roll on the camera to disorient the audience. Framestore achieved this in post, digitally extending the set and actors’ costumes to create a circular shooting format that could be rotated continuously throughout the sequence with perfect editorial continuity.

“Ultimately, The Midnight Sky is a character piece, a drama that needed to be complemented by the VFX rather than letting them take over,” says Lawrence. “I think what we did, and the collaborations involved, are exactly what contemporary filmmaking should be about.”

Visual effects studio One of Us handled a variety of conceptual and storytelling challenges. Oliver Cubbage, One of Us supervisor, travelled with Kasmir to La Palma to film background plates that provide the backbone of the planet K23 dream sequence. “La Palma’s beautiful, alien- looking landscape was the perfect backdrop to build upon to realise this new world. Close-up green screen shots were then filmed in a studio with Felicity Jones who was far enough along in her pregnancy to not be able to travel,” says Cubbage.

Once One of Us had constructed the digital environment for K23 they explored the creative storytelling challenges of the holographic environments onboard the spaceship, an interactive three-dimensional table and computer game astronaut Mitchell interacts with.

Collaborating closely with Kasmir and Clooney, they designed the look and feel of the emotive set pieces of the holographic environments which provide important character-building moments and shed light on their back stories. “We were sensitive in how we treated these shots so they wouldn’t end up feeling gimmicky,” says Cubbage.

Other holographic environments were designed to tell the story of the Aether ship’s journey from K23 to earth. “We felt these sequences should be downplayed from an aesthetic point of view. The shots are simple and elegant and designed to inform rather than distract from the actors’ performances.”

The team created the interactive map table in a similar vein, featuring just enough information on display to support the actors’ performances without being distracting. “The table needed to feel like something from the future, but not too far into the future, harmonious with the other digital devices seen in the rest of the film,” says Cubbage.

Helicopter Film Services captured aerial plates on the island of La Palma for use in post. The aerial unit also took the production crew on an island-wide aerial recce and ferried them up the mountain on shooting days. Aerial unit equipment included a Shotover F1 stabilised platform; Alexa Mini LF camera body; Fujinon Premista 28-100mm large format zoom lens; an Airbus AS355N Twin Squirrel helicopter for filming; and an Airbus EC135 helicopter for cast and crew transport. Drone unit equipment included the company’s custom-built First Person View drone and GoPro Hero 8 camera body to create an animal POV shot for VFX to use for a monkey chase sequence.

Some of the sequences Ruhe is most impressed by integrate CGI seamlessly. “I love the spacewalk and Maya’s story that unfolds in that moment. It’s such a powerful combination of CGI when everything comes together because we collaborated to design the shots.

“I’m also proud of the end of the snowstorm scene which sees Augustine collapse as the sun breaks through and he finds Iris. You would not know which parts of that were shot in Iceland and which were filmed in a stage in Shepperton. “I just love the scope of this project and what we made possible. I’ve never done anything quite on that scale or which was that demanding, and yet I think we achieved what we set out to do in a delicate and sensitive way. That’s one of the great things about working with George – he trusts his team and allows you to discover which helped make this journey so beautiful.”