Rocket Science

Linus Sandgren FSF / First Man

Rocket Science

Linus Sandgren FSF / First Man

BY: Ron Prince

Originally, Linus Sandgren FSF planned to be an illustrator before becoming an Oscar and BAFTA Award-winning cinematographer responsible for La La Land ; as a teenager he was exposed to a variety of cinematic offerings as his father was the head of distribution for Sandrews [a Scandinavian film distribution company] and brought home videos of The Decalogue by Krzysztof Kieślowski, Seven Samurai by Akira Kurosawa, and Raise the Red Lantern and To Live by Zhang Yimou.

“I remember watching To Live which is such an epic story told in not more than two hours but felt like a lifespan.” The native of Spånga, Sweden attended film school in Stockholm and moved through the ranks of the camera department to have multiple collaborations with filmmakers Lasse Hallström (The Hundred-Foot Journey) David O. Russell (American Hustle) and Damien Chazelle (La La Land).

Sandgren reunites with Chazelle on the adaption of the biography First Man: The Life of Neil Armstrong by James R. Hansen, with Ryan Gosling portraying the pioneering NASA astronaut who became the first human being to walk on the Moon. Starring alongside Gosling are cast members Claire Foy, Jason Clarke, Kyle Chandler, Corey Stoll, Ciarán Hinds, Christopher Abbott, Patrick Fugit, and Lukas Haas.

“We wanted to capture both the visceral, claustrophobic space travel as well as the family life, in the most intimate and raw way, as possible.” states Sandgren, while attending the Canadian Premiere of First Man at the 43rd Toronto International Film Festival. “For that reason, I shot the two weeks of rehearsals [involving the Armstrong family played by Gosling, Foy, Luke Winters, and Connor Blodgett] with a Super 16mm camera and for a while it was just me and the actors, alone. It was to get the actors closer to each other and to integrate a camera into the kids’ environment. Also, during principal photography, we tried to keep the crew minimal so as to give them room to feel as if everything was going on for real.”

“In the beginning, Damien said, ‘I want to be immersed in a realistic way and feel like I’m going to the moon with them. How scary would it be to be locked inside this little tin can?’” recalls Sandgren. The goal was to follow in the tradition of Cinéma verité. “We looked at The Battle of Algiers, which feels like a documentary but is fiction, as well as the interior photography of the Apollo 11 capsule shot by the astronauts on Hasselblads that look gritty and dirty.”

Camtec in Los Angeles and Atlanta provided the camera and lighting equipment. “Our A camera was an Aaton Xtera Super 16mm. We converted it to HD and had HD taps onset. Our B camera was an Arriflex 416.” Other cameras utilized were Arricam Lite, Aaton Penelope, Aaton Minima and IMAX.

“We ended up choosing formats to serve the different emotions of the film,” explains Sandgren. “Kodak 7207 250D, 7203 50D, and 7219 500T served as the primary 16mm film stocks for the beginning of the story. To get the intimacy and realism we loved the Super 16mm and were grateful that the studio was all in. When Neil is with his daughter and loses her [to cancer] that was captured on Super 16mm [cropped for 2.40:1]. But for wide shots, we filmed on two perf 35mm 5207 250D and 5219 500T, push processed +1 stop, which matches better with the detail of the Super 16mm close-ups, since your eyes are drawn to smaller details of the image. When the Armstrong family moves to Houston and try to hold up a happy life, that is 2-perf pull process 35mm (2.40:1) which gave us a softer and more polished look."

The NASA scenes are push processed 5207 250D and 5219 500T 35mm making it a grittier and harsher environment. The interiors of the spacecrafts were shot on Super 16mm 7219 500T and cropped to 2.40:1, while the exteriors were push processed 2-perf 35mm [2.40] 5219 500T. The lunar surface was shot with 15-perf IMAX [1.43:1] 5219 500T, while the memories on the moon were filmed with Super 16mm and cropped to either 1.43:1, 1.78:1, 1.90:1 or 2.40:1, depending on distribution format. Shots involving miscellaneous special effects and stunts were captured 3-perf 35mm and 4-perf 35mm primarily 5219 500T push process +1. For various visual effects shots and inserts of the moon cut with IMAX, VistaVision was the format of choice.

The mainstay lens for the Super 16mm was the Canon 6.6mm to 66mm zoom. “That’s a great range for going wide or tight,” remarks Sandgren. “We found things in the moment. We also used Kowa Cine Prominar 16mm and Zeiss Ultra 16mm lenses for more poetic imagery. For 35mm, we had a 19mm to 90mm Fujinon zoom, Kowa Cine Prominar Spherical Primes, and Vintage Ultra Primes made by Camtec.”

Grading was conducted by Natasha Leonnet at EFilm. “I wanted the light to look as realistic as possible; however, we used blacks a lot as a metaphor for death, and so usually we went for a more dramatic but realistic lighting. For many times in their homes, we used 50K SoftSun for constant lighting and exposure. We also used practicals and some minor LED panels that [gaffer] Stephen Crowley made himself. But we never set up shot-by-shot lighting. We lit the room and put the camera to best tell the story.”

Sometimes Kino Flo tubes were placed into fixtures. “We gelled them green and made sure that they looked dingy as they did in the 1960s, in combination with tungstens and practicals. There’s always some sort of colour to things rather than a clean white.”

"We ended up choosing formats to serve the different emotions of the film,” explains Sandgren. “Kodak 7207 250D, 7203 50D, and 7219 500T served as the primary 16mm film stocks for the beginning of the story. To get the intimacy and realism we loved the Super 16mm and were grateful that the studio was all in."

- Linus Sandgren FSF

Principal photography primarily took place on location in Atlanta and at Tyler Perry Studios. “I had three months of preproduction along with production designer Nathan Crowley and visual effects supervisor Paul Lambert which was great because we could together figure out how to create the visual effects in camera, since we did not want to work with greenscreen. We shot the Earth scenes for 45 days until Christmas. Then we had another 25 to 30 days onstage with the crafts, including the wire work for zero gravity and gimbals. We had three different setup stages for that, plus were shooting the miniatures.”

The A and B cameras were operated by Sandgren and his frequent collaborator Davon Slininger. “If I decided to focus on one actor or a certain shot, Davon tried to find shots from a different angle. We could look back after and appreciated that randomness. Damien, and editor Tom Cross, sometimes used shots when focus is adjusted, to make the narrative feel more real.”

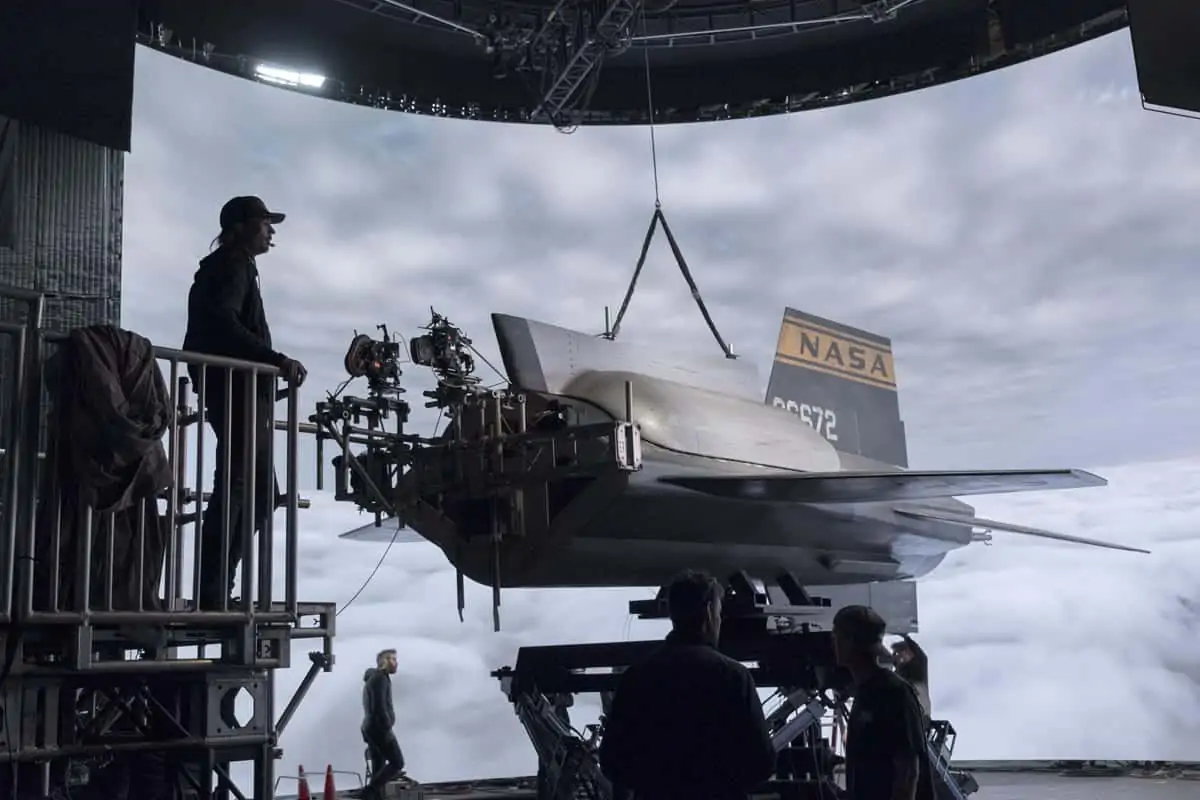

“It was crucial for us to find a way to shoot the space travel in camera,” states Sandgren. ”We built a huge 180-degree half-cylinder LED screen for both interior and exterior space craft scenes and had a splinter unit to help with the capsule window shots. Mattias Rudh FSF is really good at poetic cinematography; he came in to help us with that.”

Projections are easy to contaminate with light, especially, with a sun that travels around. “Because of the depth of field, LED screens cannot be too close to the window; however, further away, the projection becomes weaker. I was thinking if you have the craft in the middle and on a gimbal that can move and shake, it would be like a flight simulator. I figured that a good distance would be 30 feet because that’s close to infinity on a lens so when you rack focus on the screen, the Earth would be out of focus in a realistic way. And when you rack focus to the character, the screen would fall off out of focus in a naturalistic way.”

"Every film has its own needs and cinematography always has to be based in the story. It’s good to not lock yourself into thinking about things always in the same way. It’s better to try to forget about anything you’ve done and think from scratch again."

- Linus Sandgren FSF

The LED screen was 35 feet tall, 60 feet diameter had a 2.8mm pitch and was 12K across and below. “It contained thousands of screens that were like one and a half feet,” recalls Sandgren. “My rating for the Super 16 500 ASA film stock was 250 ASA. I overexposed a stop. Looking at the screen gave us a F8.5 and the light that it gave the craft was F8. It was only a half stop difference between looking at the screen from the light it gave. On top of that, we had a sun which was a 5K Tungsten Par, travelling around on a remote-controlled rig, on a circular track in the ceiling, hanging from a scissor lift that had a remote head operated by gaffer Stephen Crowley. That way we could move the light across the craft and he could aim it as the sun.”

Many different techniques were used for the LMTV scene where the vehicle was getting out of control and ending with Neil ejecting and the vehicle crashes into the ground. “We had a stunt unit shooting parallel to us on the same location” remarks Sandgren. “James Churchman [stunt coordinator] suggested using the Russian Arm under the LMTV that was puppeteered with wires from mobile cranes, to make it look like the LMTV was moving. We had an A-Minima attached to a stuntman flying out of it in sync with an explosion below, but for the close-ups Ryan was shot on a gimbal that was placed on 10 feet high platform, next to the stunts, in the same light.”

Plates were shot at Cape Canaveral in Florida for when the astronauts travel up an elevator alongside the Saturn V rocket. “Paul Lambert built that trip in CGI and it was projected onto the LED screen situated outside the window as a panorama. The elevator was built on a gimbal and the window was scratched and made to look dingy. Nathan Crowley had beams coming down outside so we could have the entire journey including opening the doors and having them step out.”

A dramatic scene occurs when Janet Armstrong (Claire Foy) insists that her husband speak to their two sons about the possibility that he might be killed during the moon landing mission. Practicals, covered wagons and LED tubes provided the lighting. “We shot the entire sequence handheld from Neil packing in the bedroom and going into the bathroom, then her chasing him down the hallway into the office where she screams and tears up,” explains Sandgren. “It built up from subtle irritation into that explosion. Claire Foy is such a great actress; she could fool around in-between takes, and go back into character to do it again. I was fortunate that Ryan and Claire could do that scene in one long take. What we did was try to do what wasn’t done in the previous setup, but I would always end up in-between them in the office. If I had been in the first take more on Claire for certain lines and him on other lines, I would do the opposite on the others.”

Rather than rely on CG, the moon was built outdoors in a quarry situated outside of Atlanta under the supervisor of Nathan Crowley. “Stephen and I discussed different options in how we could light that large area,” remarks Sandgren. “It was planned to be 500 by 500 feet but ended up being larger. I calculated that if we had two 100K SoftSuns we would have 5.6 [focal length] which would be good for the lenses of 500 ASA of IMAX cameras with the Hasselblad lenses. It would be 5.6 at the craft, 500 feet away and almost 200 feet up in the air on cranes. We went to Luminys and David Pringle [invented Lightning Strikes and Luminys SoftSuns] in Los Angeles to test two SoftSuns at that distance and walked around checking out the shadows. We’re happy with the exposure, but it still had that softer quality to it.”

A request was made for a 200K SoftSun. “David built us two 200K SoftSuns so that we had one spare. This 200,000W single source light is what we used for the big wide shots. It was incredible.”

"It was crucial for us to find a way to shoot the space travel in camera. We built a huge 180-degree half-cylinder LED screen for both interior and exterior space craft scenes and had a splinter unit to help with the capsule window shots."

- Linus Sandgren FSF

The moon landing was given the large format treatment. “We decide that since Super 16mm is the most human and intimate format, IMAX would tell the opposite story,” explains Sandgren. “Inside the craft is a grainy intimate claustrophobic environment on Super 16 and as they open door and you’re sucked out into a nonhuman, surreal but also serene landscape shot in IMAX. The moon surface is so dead and grey that we thought it was interesting to see that detail even though it’s so monochromatic.”

Key crew members were gaffer Stephen Crowley, camera operator Davon Slininger, key grip Tony Cady, first assistant A camera Jorge Sánchez, and first assistant B camera Andy Hoehn Jr., while the grading took place at EFilm with Natasha Leonnet serving as the colourist. “We created a LUT for the project that was based on the one that we had for Battle of the Sexes. It’s basically a Kodak print emulation. Matt Wallach was the dailies colourist at EFilm.”

“What I loved about the cast was that they feel like ordinary hard-working people, not superheroes,” notes Sandgren. “It was the whole documentary style of doing things that made it intimate and great in that way. We were discussing things onset together how to approach the scenes and they wouldn’t find themselves among C Stands, lights, flags and monitors; that would be pushed aside and light would come from windows or we worked with practicals. Every film has its own needs. Cinematography always has to be based in the story. What does the script want? What does the director’s interpretation of script want? How does this translate into a working methodology? It’s good to not lock yourself into thinking about things always in the same way. It’s better to try to forget about anything you’ve done and think from scratch again. What does this performance need? How should we light it? Should it be theatrical or real? In this case everything was supposed to be real.”