DARK FORCE

Cinematographer Laura Bellingham was instantly hooked by the premise of The Power – BAFTA-nominated Corinna Faith’s directorial debut – since long-time collaborator and friend Matt Wilkinson of Stigma Films mentioned it back in 2017.

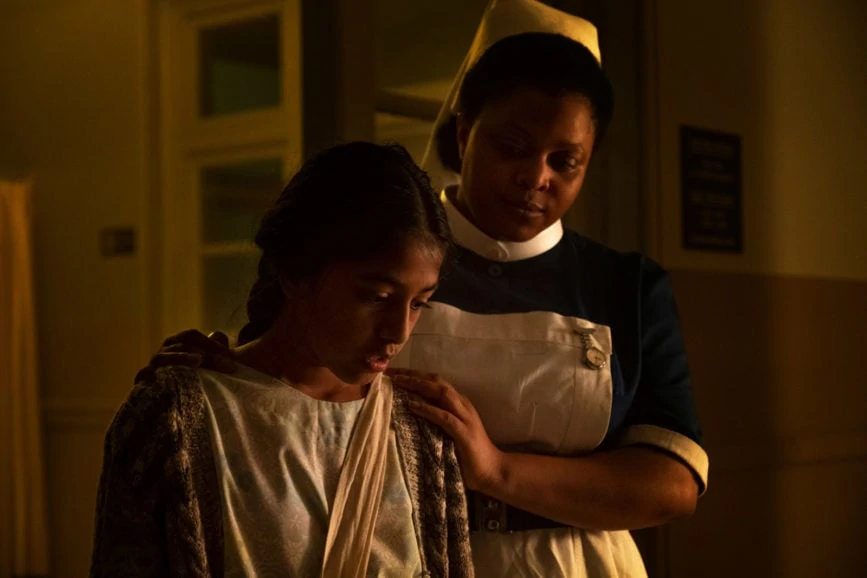

Set in London in 1974, as Britain prepares for electrical blackouts to sweep across the country, The Power sees trainee nurse Val (Rose Williams) arrive for her first day at the East London Royal Infirmary. With most of the patients and staff evacuated to another hospital, Val is forced to work the night shift, finding herself in a dark, near empty building. Within these walls lies a deadly secret, forcing Val to face both her own traumatic past and deepest fears to confront the malevolent force that’s intent on destroying everything around her.

Cinematographer Laura Bellingham was impressed by writer-director Corinna Faith’s use of a classical haunting premise to explore themes of silenced abuse within hierarchical institutions. “I found it interesting that The Power had a distinctive sense of place and period setting that was on the surface ‘other’ but in fact chimed with issues still prevalent today,” she says.

It was that connection and collaboration with Faith throughout the filmmaking process that stood out to Bellingham: “Sometimes when you are making a film, you have the strange sensation of living within the film, and thanks to Corinna and our amazing location cast and crew definitely felt that on this shoot.”

Commenting on the making of the film, Faith says: “While I was writing the script, I read a good description of what a ghost story classically is; a disturbed spirit has an issue that a protagonist, usually female, needs to understand and solve and then the spirit can rest in peace.

“This description resonated with me. I was already telling the story from a female point of view and wanted the female experience to inform the horror elements. But I was writing during the explosion of resistance to silence and passivity that came with the Me Too movement. And it felt like the landscape was changing to some extent. The idea that an angry spirit could neatly be put to rest, made quiet at the end of a story, felt plain wrong. This gave me an interesting trajectory.”

MULTI-DIMENSIONAL DARKNESS

Having similar taste to Faith, Bellingham was able to easily tap into the director’s precise vision. “The jumping off point was the visual meeting place of what was essentially a traditional English ghost story with Korean and Japanese horror. There was something very interesting in this, especially when it was transposed into the ‘70s setting,” she said.

Thematically, Faith was interested in silence, obedience, and power around a case of possession, when the body’s agency is overpowered by an external force, whether that is the force of an abuser or a ghost possession. Possession becomes the tool the ghost employs to find its voice. “We started to explore how the camera language could engage with the three key female characters in the story and reflect their experience, and how we could pay homage to our gothic and Asian horror references while trying to do something unique to Val’s journey,” says Bellingham.

The way colour and darkness would be used was a prime focus from the outset. Bellingham wanted to explore how to give the darkness a visceral quality and character. “We were conscious very early on that the darkness needed to have a three dimensionality to it, a texture for the audience to engage with it. A black screen just feels flat,” she says. “We liked that sometimes it feels claustrophobic and sometimes infinite, it always lurks around the edges of the frame. With our gaffer Ben Millar, we quickly created shorthand for the varying degrees of darkness.”

A Tale of Two Sisters (2003) and The Innocents (1961) were the filmmakers’ primary horror references, along with The Shining (1980) and The Haunting (1999) for building a sense of place. To explore the psychological side of the protagonist and fractured female identities they also sought inspiration from Robert Altman’s 3 Women (1977) and Images (1972) along with Jose Larraz’s Symptoms (1974) which Bellingham refers to as “feeling deliciously ‘70s”.

As the film takes place over the course of one night and is entirely interior, bar one scene, almost everything was shot in Goodmayes Hospital, a disused Victorian mental hospital in east London. “We were really lucky with that location for its history and authenticity,” she says. “The sense of scale, although daunting, was a huge ally.”

The crew tented the main hospital ward at the beginning of the shoot and then moved into splits when shooting the corridor scenes. “The corridors were huge and challenging and there was no way we could afford to light consistently from one end to the other which meant we had to be quite creative in our approach,” she says. “Sets were built within the hospital space for certain scenes such as Val’s bedsit and the school while the stairwells were shot at Blythe House.”

During the seven-week pre-production period, Bellingham and Faith watched a vast collection of films, visited the primary location Goodmayes Hospitalas often as possible, and looked at ‘70s archive hospital footage with designer Francesca Massariol, who Bellingham has worked with several times.

“Francesca is fantastic, and we’ve developed a shorthand,” says the DP. “Due to the budget restrictions, we knew we couldn’t dress large spaces with an abundance of vintage décor and hospital equipment, but we could paint, so we sought to create a distinctive look through the hospital sparseness and its colour coded wards, landing upon our key ward colours: blue, green, brown, and yellow. We also used the red of the generator room that we wanted to fully saturate the frame with at key pivotal moments.”

HEIGHTENING THE PRESENCE

The shoot took place from mid-August to mid-September 2019, with three pickups days the following February. Bellingham chose to shoot with the ARRI Amira – provided by 1st AC Kieron Jansch’s company Manned Camera – as she knew it could deliver the look and ergonomics needed while keeping costs in check.

Bellingham paired the Amira with the Cooke Speed Panchros which she had “fallen in love with” when using them on her previous feature Amulet (2020). “I like to team them with light SFX filtration,” she says. “We also had an Optimo Zoom come in for some specific story beats.”

With a busy schedule ahead, Bellingham and Faith created a comprehensive shot list. They wanted to be deliberate about how and when to use movement – in scenes such as those in the darkness with Val – to resonate with the audience.

“The real world of the hospital is quite rigid, so we looked to create more fluid moments to signal the arrival of The Ghost and heighten her presence with the camera. The Ghost is omnipresent, she is in the mortar of the building’s walls,” says Bellingham. “Our wonderful grip Chris Jordan and Steadicam op James Poole were instrumental in turning the camera into the Ghost’s subjective viewpoint, observing or hunting Val. Chris would get the camera elevated in ceilings and James would glide down corridors, or chase Val on the rickshaw at speed. We’d breakout into handheld only in quite specific moments – usually in the possession scenes, when Val loses control of her body.”

Slow motion was used sparingly as the filmmakers wanted the stillness to be felt in the creeping camera viewpoint of the ghost. “Things did get more impressionistic in the burning man scene which we shot at high speed on a track with a 15-second burn time. That was a tense morning!” says Bellingham. Overlay reflections – inspired by a close-up from The Innocents and the multiple reflections in 3 Women – were created in camera and became a form of iteration for the possession, or loss of Val’s agency.

Faith was keen to shoot singles with narrow eyelines to isolate the characters from one another and create a feeling of remoteness within the institutional power structures. The 2.39 aspect ratio helped reinforce the sense of depth and draw the audience’s eye into the distance. “The negative space played a role in the low-key scenes, hopefully encouraging the viewer to scan the empty corners of the frame looking to make out shapes and anticipate what is coming in the darkness,” says the DP.

We were conscious very early on that the darkness needed to have a three dimensionality to it, a texture for the audience to engage with it. A black screen just feels flat.

Laura Bellingham

QUALITY OF LIGHT

Having selected a specific colour palette for the wards, inspired by period hospital references, it was decided that underexposed, coloured light would best complement it. “The blue really benefitted from the soft muted look while the yellow ward involved a lot of hard tungsten sources, bounced or direct,” says Bellingham.

The main challenge the crew encountered was finding an approach to light the huge, expansive spaces within the budget. Gaffer Millar and Bellingham had to be selective and “make a virtue” of their restrictions. In the long corridors and larger wards, they created lit zones within the frame. “We were confident that as long we were preserving that shape to the darkness and creating depth, we were on the right track,” says the cinematographer. “For example, Rose could be in the foreground with her propane lantern or lit by a bedside, but the only other illumination might be a soft moonlight wash on a doorframe or a distance spectral highlight 100 yards down the corridor behind her.”

Moonlight was an important touchstone within the story, as was how it played in tandem with the mustard yellow of the main ward. Faith and Bellingham had a shared aversion to hard, blue moonlight and believed it would be more fitting for the story if the moonlight had a desaturated ashen quality which can be seen in the ash that floats in the ward and is associated with the ghost and in the film’s climax.

The quality of the moonlight was discussed in detail – what was lovingly referred to as “dead moonlight”. The yellow ward, where most of the night action takes place, was tented. Millar then pushed soft, dimmable daylight sources – mainly Kino Flos – through calico to glow the windows and carry a little way into set.

“The calico warmed up the moonlight to take us away from the steely moonlight look,” says Bellingham. “During the scenes when the hospital generator loses power, the grey moonlight was extended into the space via bounced LiteMats overhead.”

Interior sources were used sparingly. There would always be a fall off into ‘the dark end’ somewhere within the frame. “Ben joked about spending a third of our lighting budget on rigging and on making things darker in an already dark film,” says the DP. “We’d even end up switching off tubes in the Kinos as they felt too lit.”

As the daylight interiors were all set in the side of the building which saw the sun for most of the day, the crew embraced that look, controlling it the best they could for those moments. Colourist Jat Patel at Molinare later brought a “soft dense feel” to the highlights.

The quality of the various practical sources inspired the filmmakers to create a variety of effects. For instance, Rose’s key was often the propane lantern she carried which was diffused through its housing. “We also played with angle poises bouncing into the hospital beds,” says Bellingham. “Rose and the other actors responded to the lighting on set in creative ways, the best example being when Neville uses the beam on his head torch to intimate Val in the darkness.”

Colourist Patel then brought the daytime and night-time worlds together “while staying faithful to the colour palette”. He used a custom film emulation with a very soft curve and added grain to bind the look together. “He also played with the oil burner’s illumination to give weight and density to it throughout, as to almost make it a character against Val’s fear of the dark,” says Bellingham.

FINDING A VOICE

In The Power, possession becomes the tool the ghost employs to find its voice. In one scene Val is thrown around like a rag doll by an unseen force. “Rose Williams, who plays Val, did an incredible job,” says Bellingham. “She and Corinna choreographed the movement in rehearsals like a dance, the intention being to recreate the kind of shapes you might witness during an assault, and what that might look like if the attacker were invisible.

“We then brought the camera into rehearsals and looked for ways I could respond to that dance handheld. There was a raw physicality to this scene, and I think the end result is quite shocking, seeing Val’s loss of autonomy, especially once the audience understands the possession is a recreation of an unseen assault that the ghost is trying to ‘bring into the light’.”

Some scenes required a close collaboration with the visual effects team, such as the ash effect that swirls within the frame during the haunting sequences. “We’d wanted to capture the ash directly in camera using oxy-acetylene, but we quickly realised this would be too time consuming. Instead, we decided to shoot ash plates concurrently to A unit,” explains Bellingham.

“Kieron switched over to head up a B unit for this with the SFX team and VFX supervisor Mark Wellbrand. They tested various materials fired through fans for the ash on different backgrounds with different lighting set ups. They shot a range of plates both static and moving, and the results were beautifully layered into the action in post.”

When shooting any scene, time was a key consideration. “We really felt the time pressure around some of stunts, practical effects and VFX work,” says Bellingham. “They just always had to take the time needed and as a result we would have to keep other coverage flexible. Like all the other parameters we simply had to make a virtue of it by employing a bold camera language around developing wide shots and sparse coverage.”

Bellingham feels The Power – her fourth feature – is the first time she felt a real confidence to make those bold choices. “In the journey to its completion, I felt there was a satisfying alignment between our intention and the ultimate realisation.”

Photo credits: Laura Radford and Rob Baker Ashton

Laura Bellingham is represented by Casarotto Ramsay & Associates