Vanishing Act

Jeff Cronenweth ASC / Gone Girl

Vanishing Act

Jeff Cronenweth ASC / Gone Girl

With the symbiotic relationship between cinematographer and director that oozes off the screen during David Fincher productions, you’d think that Jeff Cronenweth ASC had shot all of the acclaimed director’s movies. However, it seems that about half a body of work is what it takes to get that kind of collaborative bond.

For their last three productions together – The Social Network (2010), The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo (2011), and now the psychological thriller Gone Girl – they’ve stuck with the same format, choosing to shoot on RED cameras with a widescreen aspect ratio at 2.35:1.

“We both feel it (the aspect ratio) tells great human stories and allows people to interact within a frame,” said Cronenweth, just days before he entered the Digital Intermediate sessions with Ian Vortovec at LightIron. “It gives space for the characters to get more involved with the scene, to be more a part of it, in the wide format.”

Due mostly to uncanny timing, on the camera front Cronenweth has gotten to be one of the pioneers with RED’s newest accessories on each of his Fincher films. On The Social Network he and Fincher were among the first to utilise the RED One Mysterium-X sensor package, with its increased colour space and 4K resolution. Then on The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo they got to work with the just-released RED Epic with its 5K resolution and enhanced dynamic range/latitude capabilities. Now they’ve used the RED Dragon package on the Gillian Flynn-adapted screenplay starring Rosamund Pike and Ben Affleck.

“The Dragon’s 6K sensor allows you to photograph at 6K, giving you room to reposition, and stabilse – all things David is a fan of – and then to down-res to 4K,” explained Cronenweth. “In a 6K format there's only a certain amount of glass available that actually covers the sensor without vignetting.”

This opened up the doors for testing some new lenses in conjunction with the RED Dragon, leading them ultimately to the Leica Summilux-C line.

“We’d done the previous two movies on ARRI Master Primes, which we love,” he said, “but David wanted to try and go for something more compact, a smaller footprint, never mind the fact that it was necessary to be able to cover the 6K sensor. We have always been Leica fans, as they seem to capture a softer side of a face while maintaining their sharpness.”

Gone Girl – the suspenseful tale about the disappearance of a man’s wife and the intense media circus surrounding it – is a mystery first and foremost. Cronenweth’s challenge was finding a way to keep the audience suspended in what would initially be a very mundane environment.

“I was looking to create a visual world and style that allowed the actors to play this mental chess game with each other without giving their characters away,” he said. “I wanted to add visual contrast and emotion, but still in the context of this very pedestrian lifestyle that they find themselves in, which then starts to fall apart.”

Cronenweth and Fincher were intent on capturing a middle-of-summer, small-town Midwest look, and shot in Cape Girardeau, Missouri to do so. It plays a large role in how the characters interact with the surroundings and with each other. It actually is an intimate Midwestern town, and so played into the tone that havoc and mystery can create in a small community.

"I was looking to create a visual world and style that allowed the actors to play this mental chess game with each other without giving their characters away."

- Jeff Cronenweth ASC

One of Cronenweth’s favourite sequences in Gone Girl take place in an abandoned shopping mall. Everything besides the stairwells had been stripped out of this cavernous building, leaving only vagabond remnants and exposed mechanics of escalators. In the mall there is a scene where a detective goes searching for answers in what is now a drug-infested squatters’ palace.

“It had one existing fluorescent light left over from what looked like a pharmacy,” he describes. “Otherwise, the entire mall was black and it was enormous. There were three stories and you could see hundreds of feet in each direction. Lighting that, both economically and physically, was an enormous challenge. Ultimately I still wanted to maintain the abandoned feel – that the electricity had been turned off, and things lurked in dark corners.”

Cronenweth used the torchlights that the detectives used in the scene as the main source and hid little Tungsten light bulbs around them. There were a couple of fires that they had burning in various rubbish bins and a little illumination coming through the skylights which acted as their main key.

“We ended running miles of cable,” he says, “but utilising very small sources in a lot of different places.”

Overall, Cronenweth’s goal for lighting the film was about experiencing the separate parts of each character’s journeys.

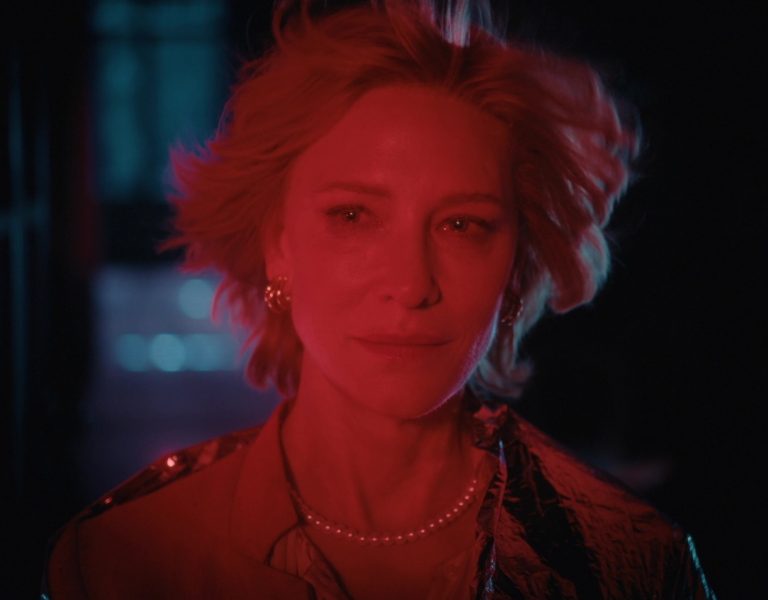

“Amy Dunne’s (Pike) journey changes drastically,” he offered, “and so does the world she lives in. So her perspective is really different. Trying not to sound too vague – as there is so much I can’t talk about in order not to give anything away – when the couple’s story intertwines, there’s a much more plush and comfortable look. Amy comes across as very confident and in control, and it was imperative to let her have that room for her character, to be strong in those situations. When she evolves into something else, or journeys away from that world, we allowed it to be a little looser and not as delicately crafted – lens sizes were slightly less forgiving and we allowed her to kind of meld into these awkward environments that she finds herself in later.”

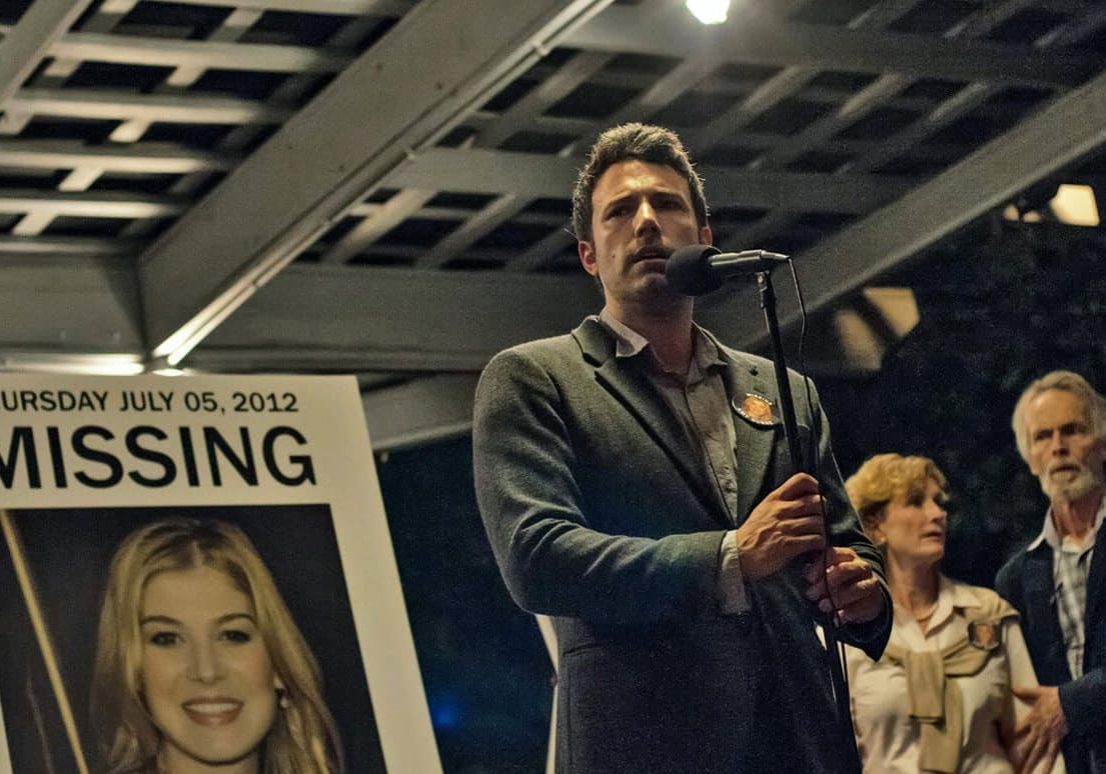

Nick Dunne (Affleck) spirals downward as realises the situation he’s found himself in. He continually crumbles and loses control up until the point he decides to take it back a notch, and with this and Amy’s evolution, Cronenweth got less cosmetic with his lighting choices, using more practicals and allowing different colours to come in to play, kind of polluting the environment and going for a more harsh ‘reality’ look, if you will.

In response to whether he thinks dramatic stories are his wheelhouse and where he’s most comfortable, Cronenweth resists being pigeonholed.

“I think that some of my aesthetics tend to play better in those kinds of stories,” he says, “but I don't think it's exclusive by any means. If it were the right comedy or the right sci-fi, I would happily try that. I did one called Down With Love (2003) that was a very bright romantic comedy with a 1960’s aesthetic. I still think you can find my light in there, regardless of it being quite a different world from something like Dragon Tattoo.”