Home » Features » Production Profiles »

ARTISTIC FREEDOM

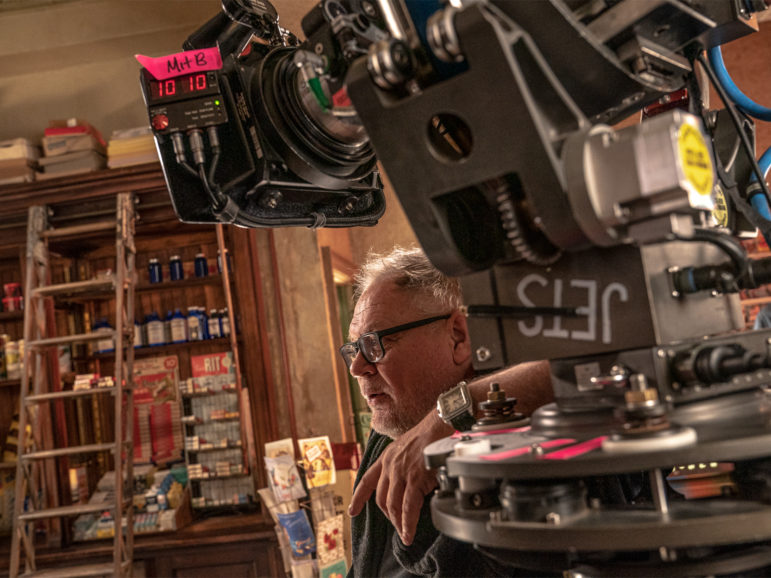

The great Polish born American cinematographer has a seventh Oscar nomination for his nineteenth picture with Steven Spielberg and he is still striving for perfection.

You cannot understand Janusz Kamiński, his extensive relationship with Steven Spielberg nor their latest collaboration without appreciating the cinematographer’s “nostalgia for bleakness.”

This is a deep-rooted philosophy of art and cinema as a political medium stemming from Kamiński’s background growing up under Soviet controlled Poland in the ‘60s and ‘70s.

“We had a social realist genre of cinema where filmmakers learned how to use period drama to reflect contemporary issues,” he says. “We Poles learned how to read between the lines.”

At that time, Poland was a nominally independent country run by the local communist party under the influence of the Soviet Union.

“Poland was more liberal than other Eastern European countries because we had private ownership. Farmers owned plots of land, there was a form of entrepreneurship. Because Russian troops were stationed in places like Czechoslovakia, you’d see their presence everywhere, but Czech stores would be full of food. In Poland, the presence of the Soviets was less but we had more artistic freedom. So, art prevailed for the sake of commerce. An ideology which valued the artistic and intellectual value of a person over material possessions, was part of my growing up. It’s one reason that I make movies.”

Classic Hollywood cinema – including the 1961 adaptation of West Side Story – was denied to East European audiences. They were, though, able to watch the American new wave cinema of the 1970s “which not just questioned and analysed the socio-political state of the United States (at that time) but also made very strong ideological statements that were inspirational to my generation.

“Films like The Panic in Needle Park, Vanishing Point, Taxi Driver, Midnight Cowboy had violence, sex, and drugs, and showed America in a bleak decadent way. Those were accepted by the Polish censor which meant we could watch them and therefore became a tremendous inspiration for young Poles because we wanted to rebel.

“I was a viewer then and those movies were why I wanted to come to America and why I want to question, evaluate, and inspire in my movies.”

Mainstream releases he was permitted to see in Poland included Saturday Night Fever (“I was just puzzled”); Kubrick’s 2001 (“I was puzzled”) and Earthquake (the 1974 disaster movie which was “laughable”).

Kamiński had not been exposed to this type of cinema. “I couldn’t identify with it. We lived in such an environment where bleakness was what we fell in love with.”

Coming to America

When Martial Law was imposed in 1981, 21-year-old Kamiński emigrated to America and “discovered the beauty of cinema as entertainment. It was a cinema that takes us to another level, a fantasy, larger than life. That did not exist in Poland.”

He watched films to learn from greats like James Wong Howe (The Sweet Smell of Success), Stanley Cortez (The Night of the Hunter), Gregg Toland (Citizen Kane), and Bruce Surtees (Lenny) and how they used Giant Arc lights.

“Imagine making Grapes of Wrath with 30-40 ASA and using Arc light as a candlelight – what a masterful way of making movies! Movies where you had 20-30 Arcs and each one has their own electrician, all controlled by the DP. Those are the movies I wanted to make.

“That’s why we love working together, Steven and I. He has worked with guys like Douglas Slocombe BSC ASC (Indiana Jones) who come from a background in classic movie making. We have the ability to recreate the world of past cinematographers and West Side Story is the best example of that.

“When you have 20-40 dancers moving through the frame, we want the whole thing to be sharp to appreciate the foreground, mid, and background all in focus. Our night exteriors are shot at 400 ASA at F 8 or 11. That requires a lot of light.”

A climactic fight set in a salt shed with high windows, afforded Kamiński the opportunity to build an elaborate rig involving klieg lights mounted on cranes. The idea was to have a mix of headlights and brake lights shining through at intervals.

“The ‘America’ sequence was shot over several days because we shot in different sections of the city. In terms of schedule that meant we’d set up in one location and shoot other scenes there on that day also, so when ‘America’ has to look like one continuous sequence I need consistency of light.

“If you shoot at high noon when the light is horrible you can see, when you look at the movie, where the shadows are. Although we’re shooting at different times of day, I had to match light those locations to a late afternoon. It looked overlit on set, but with the aperture closed down it looks great on screen.”

Colour on screen

He credits the actors with how gorgeous the movie looks. “It’s because they are dancers. They are very precise with their movement – like a stuntperson – so we could be precise with the camera, travel with them or lead them and put lights in exact positions, knowing they will hit the mark. This liberates the camera.”

The filmmakers’ homage to musicals is important. “Whether you like Broadway shows or not, you can’t fail to be impressed by the razzle and dazzle. Sure, you may not like the lyrics or the music, but you come out with a sense of spectacle. That was my blueprint. Not necessarily West Side Story, which I have not seen live, but other musicals.

“Each time I go to New York I want to see a Broadway show because it is so visually stimulating. So, with West Side Story, there are certain expectations of the musical that we didn’t want to break from.”

Kamiński’s understanding of colour – which he credits Vittorio Storaro ASC AIC (The Conformist) for – is on show in West Side Story.

“He made us all aware of the reason colours exist. The power of colour. When you have that knowledge, you can tell a story with colour. Colour creates a three-dimensional sense of space.”

Take Anita’s apartment. Spielberg, Kamiński, and production designer Adam Stockhausen conceived her as a seamstress who dyes and hangs fabrics across the room, that she will sew into dresses.

“This yellow, orange, pink, and red motif repeats throughout the movie. With the fabrics draped over the room I could backlight them and create a bit of a mystery between the interaction of Maria and Tony. It means they can touch and kiss each other but nothing too obvious. With the flaring of the lens and back lighting I could create silhouettes, yet you see through the fabric and see their expressions.

“With ‘America’ there are no tricks in terms of colour, but the scene is so colourful because of the wardrobe. The colours were saturated because I was pumping so much light onto the scene and since I was lighting frontally all those dresses were popping.”

The stained glass in Anita’s apartment that divides the sewing room from the bedroom (plus a window in the door with colourful gels) is mirrored in a duet between Tony and Maria set in the Met Museum cloisters in downtown Manhattan.

“That was Steven’s idea. We had to reshoot because I failed in terms of the colour palette and the light movement we got with the stained glass. I could see with my eye the colour changes but when we saw the film it was not as clear. We put extra gels into the glass window and developed a better technique to effect a slower change of colour as the scene progresses. Magenta, orange, some blue and red is the motif.

“I also had a great gaffer Steve Ramsey, and key grip Mitch Lilian, and operators Mitch Dubin SOC and John “Buzz” Moyer SOC ACO - but the musical territory was new for all of us.”

Dubin and Moyer won Camera Operator of the Year in Film at the SOC Awards and BSC Awards.

Beneath the surface

Disney’s $100m budget enabled epic storytelling, such as being able to shoot huge lit and dressed sets in 360-degrees. But for all the sheen the story’s political parable is not lost on Kamiński.

“This is not social realism, but it has themes that resonate with an audience after 60 years. That’s why Steven decided to make this movie and it’s sad we even have to. We progressed until Trump and then regressed 30 years. America had grown through decades of political demonstration and social awareness until it became tolerant – on the surface at least – and then in four years Trump brought ugliness back into this country.

“Our film reminds people of how necessary it is to be tolerant and respectful and to realise that those differences still exist perhaps even more so than before.”

Film is how we make movies

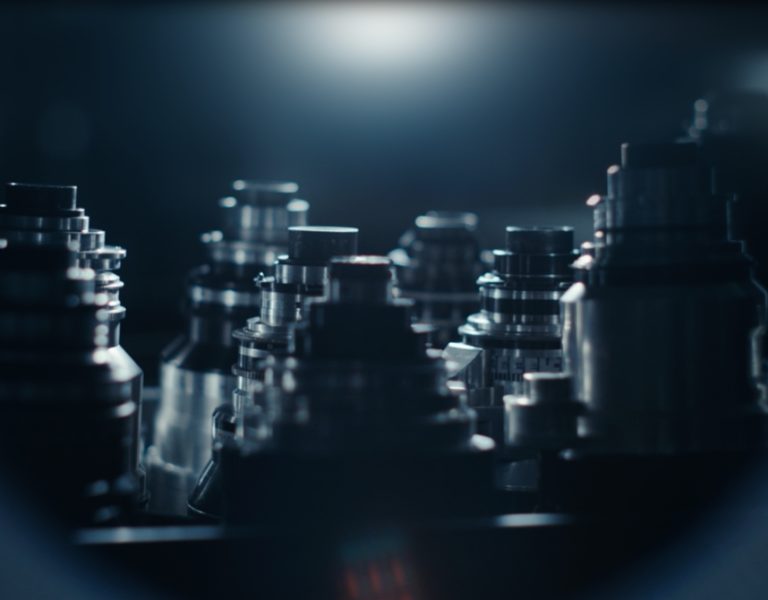

West Side Story was captured on Panaflex Millennium XL2 with variety of Panavision glass – C-Series, Panaflex Millennium, T-Series. Kamiński shot a mix of high speed, daylight, and medium speed emulsion 35mm (Kodak Vision3 250D 5207, Vision3 200T 5213, Vision3 500T 5219).

“The chemical part is essential to what the movie looks like. I miss the ability to create that image because you can’t recreate that in digital. I’ve done tests. It’s a different animal.”

He and Spielberg are staunch adherents to celluloid, with Kamiński in particular lamenting the loss of the skill of silver retention (bleach bypass). Learning the trade in the 1990s, he realised there was more to it than lighting, composition, filters, and lenses.

“Film is how we make movies. We like the discipline, the rigour. I like the mystery of film, am I exposing the film well? Now, because of digital dailies, when I see a print, it will not resemble anything we are familiar with! Everything is geared toward digital post now. Plus no one really knows what a film looks like anymore.

“I resent the whole philosophy of embracing digital media without giving any consideration to what it does to an artist who wants to tell the story through cinematography. We are being robbed. I don’t want to be part of the group that embraces digital.”

Digital tech has improved, Kamiński admits, to the extent he finds it harder to know what was shot on film or sensor, but he says the damage has been done.

“The artform has become neutralised. It’s not what it used to be when Bob Richardson was doing U-Turn, when Rodrigo Prieto shot Alexander, and [Newton] Tom Sigel was doing amazing stuff.

“When Philippe Rousselot (Dangerous Liaisons) shot dark scenes, he knew what he was doing with China Balls. Now everyone shoots dark, and anybody could have shot it. Pictures are so murky you need to crank up the TV to see it. People think they are artists [by shooting dark] but they are not. They just don’t know how to light.”

Mostly he misses the ability to craft with film, using cross processing or silver retention and seems resigned to its fate.

“It was a great artistic tool.”

Kamiński has made all of Spielberg’s movies since Schindler’s List and naturally counts that war story along with Saving Private Ryan (his dual Oscar winners) plus Lincoln among his favourites.

He believes Munich to be underrated “the storytelling is so strong and it’s such a departure for him…it’s not a happy ending” and is proud of their work on AI, especially in terms of “cross process manipulation and using reversal stock. It was a very adventurous movie in terms of what I was doing in the lab.

“I can be critical of my work. I know when a movie I’ve done sucks visually. But you have to like your work also otherwise you’ll be miserable. You have to know when you’ve done mediocre work so the next time you’re confronted by the possibility of doing mediocre work you know how to improve it.”

And here’s the final caveat: a hint that the pair will soon shoot digital themselves.

“It’s not that we’re not willing to adapt. We’re already speaking about a project in the very near future with high definition.”