Overview: It’s Christmas Eve and Riley is ecstatic that Santa will be visiting soon. That is, until she finds out that Santa is not real… As Riley’s reality is turned upside down, she questions the lies told by adults and the terrible secret that she is forced to keep. She is forced to confront a much darker truth running through the seemingly happy family.

What were your initial discussions about the visual approach for the film? What look and mood were you trying to achieve?

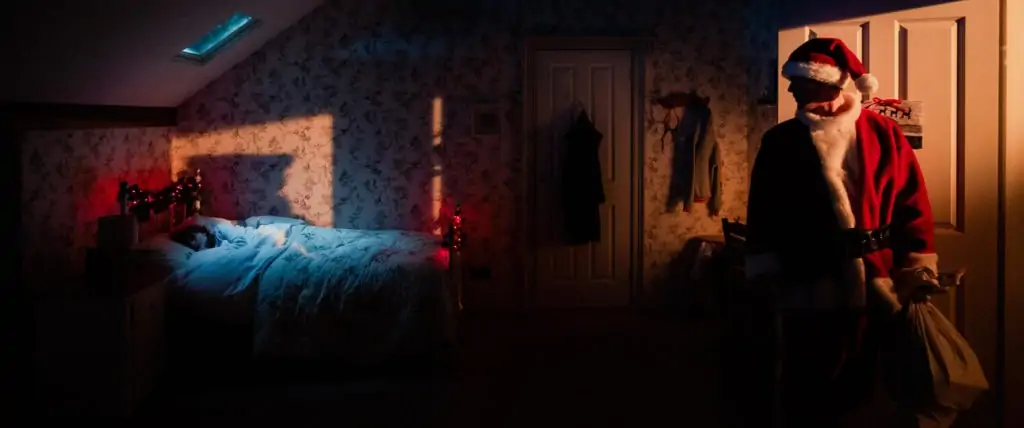

When She Was Good is a film that operates in a delicate space. Told through the experience of a child, we didn’t want to go down a blue, dark, social realist route. Instead we wanted to use colour and saturation to mimic Riley’s frame of mind and carry the audience into the story emotionally through light. We played a lot with natural blues and oranges, then, given the nature of the film, the red of the Santa suit took on a sort of power and we were compelled to work red into as many frames of the film as possible – be it through lighting or set design. The film has a very dark theme lying at its core so our main concern was treating this delicate subject with the sensitivity and maturity it deserved. It all stems from the emotion.

What were your creative references and inspirations? Which films, still photography or paintings were you influenced by?

We talked a lot about the representation of Christmas in the films Carol and Paris, Texas. The sensitivity of Ed Lachman ASC’s camerawork is a particular inspiration, keeping the audience in the minds of the characters and giving a clear perspective to the camera. We wanted to use the full arsenal of camera work so there’s some static, slow moving wide shots which open the film, adding tension and giving a more objective view of this family at Christmas. The pivotal turning point happens in the middle of the film which marks a shift in the camera work and the saturation. We become much more frantic and anxious with Riley as she struggles to communicate what is happening to her.

We looked at a lot of fairytale imagery and looked at the work of Rob Hardy BSC and other greats in terms of anamorphic framing and the use of natural light. I never really want my work to be noticed or to outshine the story – it is there to be felt.

What filming locations were used? Were any sets constructed? Did any of the locations present any challenges?

We had a big house in Oxfordshire and had to build Riley’s bedroom in the studio at NFTS. Designer Kate Beard did a remarkable job in matching the locations and we worked together to bring light sources into the room. The window over Riley’s bed allowed me to light her from above with foreboding moonlight and daylight for the scenes set in her room.

The house presented many issues in terms of large windows and reflections. Gaffer Elena Nassati ordered all the floppies in Panalux to try to give us absolute control. Because of working hours of the young cast, we were limited to shooting day for night which posed challenges for us to overcome. I was lucky to have such an industrious lighting team!

Given the limited hours and getting used to COVID protocols, the main challenge was just making the day! I want to mention the remarkable versatility and willingness of the entire crew to rise to this challenge. It was not easy!

Can you explain your choice of camera and lenses and what made them suitable for this production and the look you were trying to achieve?

Given the fact that we had young actors, we opted for digital. The school’s ARRI Alexa Minis are small and versatile and allow me freedom to put the camera in small spaces and find interesting frames. We tested a few sets of lenses. I was very keen to shoot anamorphic to match the straight lines of the house and give a very geometric look to the film. I’ve always connected with widescreen for the breathing space in the frame. Paired with anamorphic you gain both intimacy and distance in the same frame.

I wanted to shoot on Panavisions Xtal Xpress Anamorphics or a set of Cookes but it was at a time where the industry was hotting up again. I landed a set of Kowa Anamorphics from Movietech in Pinewood. We tested and tested, with cast, various lighting conditions. Watching it back in the cinema with director Margarita Milne, there were elements we loved and some we didn’t really like. We opted for the Kowas for the softness and the nostalgia and I promised to shoot with a deep stop and avoid the wider focal lengths to keep the distortion to a minimum. Looking back, I see this as a bold choice, but the right one. The characteristics of this set of lenses give it a dreamy look that makes you feel like you’re watching a fairytale, rather than a sharp, dark, social realist narrative.

What role did camera movement, composition and framing and colour play in the visual storytelling?

The camera always mimicked Riley’s emotional state. She’s rather calm and still for most of the film, and so is the camera. We explode into handheld for one sequence but she’s quickly shut down by her mother, and so is the camera. We shot at her height, framed her close-ups tighter than the others, and always tried to shoot from her perspective. I am a huge fan of creative limitations, setting a philosophy for the camera is one of the most important parts of my work. There’s great freedom of expression in working within boundaries.

We avoided social realism. We wanted to paint a happy world up until the great reveal. The film is bathed in warm light up until it’s not – and the pivotal scene marks a real shift. Blue and red become core colours and her world becomes desaturated and lifeless. Riley’s loss of sense of self is mimicked by the colour and saturation. The warmth returns as she re-joins her family at the end, but it’s no longer cosy and comforting – everything has changed.

What was your approach to lighting the film? Which was the most difficult scene to light?

I was delighted when reading the script to see that the most pivotal scene of the film is told through lighting. Riley is bathed in moonlight, her door opens and Santa’s shadow appears on the wall next to her. The shadow moves closer and closer, drops off presents and then the door shuts, but Santa remains inside the room. Crafting the light and shadow play for this scene was essential and needed to be thought through and sensitive given the dark subject matter.

The lighting lives in the realm of heightened realism -it’s naturalistic, but pushed. There’s a lot of darkness and shadows, things lurking behind closed doors, something beneath that’s unspoken and unheard. We’re presented with a seemingly happy family but soon learn of a stomach twisting truth that needed reflecting in the light.

We spoke at length about the role of lighting. How much should we allude to a darker truth? Should we go social realistic or opt for a more heightened look? How should the audience feel, and as the film develops, how should the look develop with it? It always comes back to the emotion and everything needs justifying from an emotive level.

There’s a particular scene towards the end of the film where Riley re-joins her family for Christmas festivities – but everything has changed. We wanted to mark this moment with some high speed, handheld, similar to the final scene in Carol. We lit for 100fps with a 90-degree shutter, so I needed a lot of stop to play with. My gaffer Elena Nassati was particularly concerned by how bright I wanted the living room but when she saw what we were doing, she was totally on board. We used a gemball boomed over the staircase to toplight the entire space, giving me delightfully harsh eye shadows – it’s not a cosy warm Christmas by the fire!

What lessons did you learn from this production you will take with you onto future productions?

On the last few films I’ve stuck to a few simple reminders that help me get the best from each day, scene, or shot: “Is this the best you can do?” is glued to my monitor – thanks Stuart Harris! I make titles for each scene which helps focus the mind on the emotion I need to capture. Finally, I ask myself – what is the one image that captures this emotion? If you can get that in the can, you’ve got it and can move on.

Straight after NFTS I shot a feature thriller called Cerebrum starring Steve Oram and Tobi King Bakare, produced by Lakeside Pictures. Everything I’ve learnt in the last two years from Stuart Harris, Oliver Stapleton BSC, and all the amazing visiting tutors, led me to this moment. We achieved so much, I am proud to say I did my best work and I managed to stick to these philosophies. I love to operate and there’s nothing better than ‘feeling it’ when your eye is on the eyepiece and the camera is rolling.

My shotlists are getting shorter and shorter. I’m daring not to ‘cover’ scenes, the more I shoot, the more I understand what is needed and what ends up on the cutting room floor. I feel that my voice as a cinematographer is growing and shaping everyday I’m on set, with every challenge that is presented to me.

I shoot wider, shoot less, and shoot more confidently now. Only go in for the close-up when you absolutely have to! Presence of body and mind is the most important thing. Feel what the actors are doing, let your heart guide the next setup. Don’t match singles, give the audience more, tell a story with each frame, use more negative space and allow shots to breathe more. There’s so much more meaning when there’s fewer, more composed frames.

> DISCOVER MORE ‘FICTION’ FILMS FROM THE 2021 NFTS GRADUATE SHOWCASE

> GO TO BRITISH CINEMATOGRAPHER ‘HOME’ PAGE

> BACK TO TOP