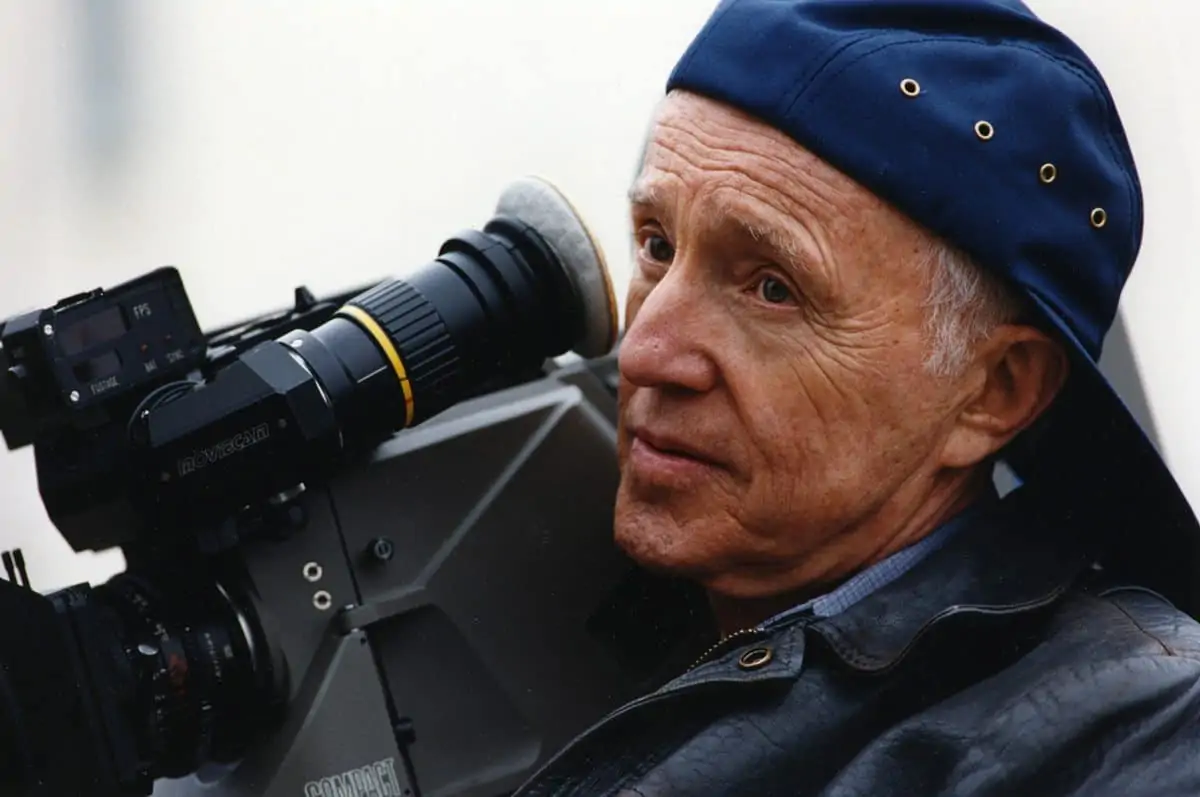

The mirth and merriment of the Christmas and New Year season were considerably dulled with news of the passing of two of the industry’s most accomplished cinematographers – Haskell Wexler, who died on 27 December 2015, aged 93, and Vilmos Zsigmond, who passed on New Year’s Day 2016, aged 85.

Wexler was nominated five times for Academy Awards, and won twice for Who’s Afraid Of Virginia Woolf? (1966) and Bound For Glory (1976). During his long career, Wexler worked equally on mainstream and independent films, fiction and documentaries, in monochrome and colour, creating a relatively homogeneous filmography, and never swerved from radical convictions that were instilled into him from an early age by his wealthy, liberal, Jewish family in Chicago. Wexler joined the merchant navy as a seaman in WWII, serving for four and a half years, and was decorated for bravery after in rescuing fellow crew members in shark-infested waters off the coast of South Africa when their vessel was torpedoed.

After the war, his father helped him to open a studio in Des Plaines, Illinois, where he produced a number of industrial films with an underlying social message. After closing the studio in 1947, he photographed documentaries by the educational filmmaker John W Barnes, including The Living City (1953), nominated for an Oscar for best documentary short. The first feature Wexler shot was the low-budget Stakeout On Dope Street (1958), directed by Irvin Kershner. In the 1960s he shot mostly B&W naturalistic dramas including Kershner’s The Hoodlum Priest (1961) and A Face In The Rain (1963), for which he is credited with inventing the handheld running shot, by running with an actor along a narrow alley. His penetrating cinematography in Mike Nichols’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? explored the faces of the two megastars, Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton, in large, unflattering close-ups as they squabbled bitterly. Wexler then turned to shooting mainstream films in colour directed by the veteran Norman Jewison, In The Heat Of The Night (1967) and The Thomas Crown Affair (1968), notable for its innovative splitscreen images and zooms.

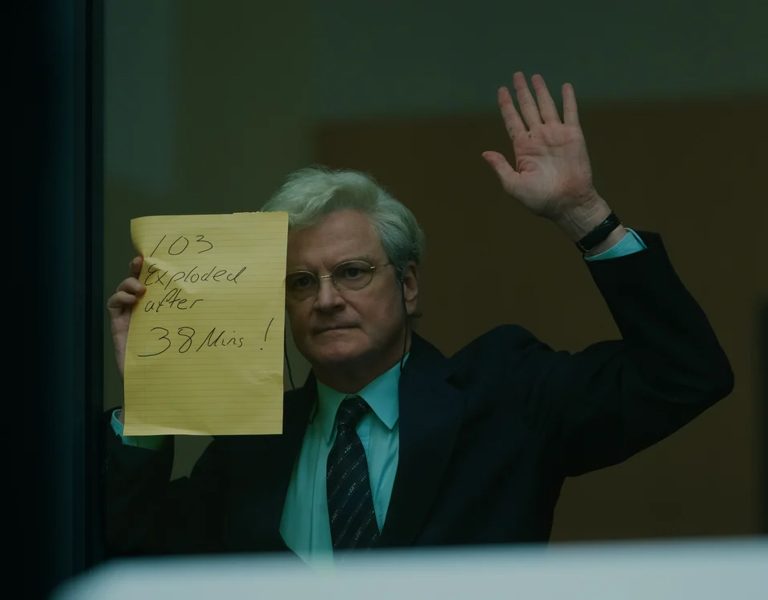

A Wexler turned back to more radical material, mostly documentaries, influenced by the civil rights movement and protests against the Vietnam War. His first fiction feature as director was Medium Cool (1969), shot during the chaotic Democratic convention in Chicago in 1968, about the politicisation of a TV news cameraman. He also shot the 22-minute Oscar-winning documentary Interviews With My Lai Veterans (1971). Wexler was fired half-way through shooting One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975) because of “artistic differences” with the director Milos Forman, and replaced by Bill Butler. They were jointly nominated for the best cinematography Oscar. Wexler’s second fiction feature as director, Latino (1985), had an underlying criticism of American support of guerrilla forces attempting to overthrow Nicaragua’s Sandinista government, and in his later years, he made films that gave voice to the voiceless – from The Sixth Sun: Mayan Uprising in Chiapas (1995) to Four Days In Chicago (2013), when

Wexler returned to his hometown of Chicago to document the Occupy Movement’s demonstrations against the 2012 NATO Summit.

Vilmos Zsigmond, the Hungarian-born cinematographer, proved a master of lenses and light and, together with his lifelong cinematographer friend László Kovács, was one of the leading photographic lights of the Hollywood New Wave. Transforming the look of feature films, Zsigmond was the man who pre-fogged his stock for McCabe and Mrs Miller and rehabilitated the often-despised zoom lens in The Long Goodbye (both for Robert Altman). He was also the pictorial author of Deliverance, and won an Oscar for his work on Close Encounters Of The Third Kind.

Kovács and Zsigmond, aged 26 and 23 respectively, filmed the Russian invasion of Hungary in 1956 and fled the country with 30 cans of raw material three weeks after the clampdown. Deemed persona non grata after giving their footage to CBS News on arrival in New York, they understood the effect of dramatic composition and the art of storytelling through images. The story of their flight was told in No Subtitles Necessary: Lazslo and Vilmos, a riveting documentary by James Chressanthis.

After a stint of shooting B-movie biker and exploitation flicks, industrial documentaries and TV spots, Zsigmond’s first notable cinematographic effort was The Sadist (1963). He then shot Peter Bogdanovich’s debut Targets, and Bogdanovich’s subsequent productions What’s Up, Doc?, and the shimmering black-and-white Paper Moon (1973). He also shot two movies for Bob Rafelson, Five Easy Pieces and The King of Marvin Gardens. For Altman’s McCabe And Mrs Miller, he took a technique (pioneered in B&W by Freddie Young BSC on the Sydney Lumet/John Le Carre movie The Deadly Affair) of pre-fogging, or pre-flashing the raw stock with a little light before exposing it fully on-set. He lit John Boorman’s cult movie Deliverance (1972) and worked on Steven Spielberg’s early comedy-thriller The Sugarland Express. Zsigmond loved working and kept going as long as he could, shooting 24 episodes of The Mindy Project. In recent times he was also co-founder, with Yuri Neyman, of the Global Cinematography Institute in Los Angeles.