In memoriam: George Spiro Dibie ASC

Feb 10, 2022

The ASC released the following statement in regards to the recent passing of George Spiro Dibie ASC:

–

An Emmy-winning cinematographer, union leader and tireless educator, he freely shared his knowledge, experience, and enthusiasm — passing at the age of 90.

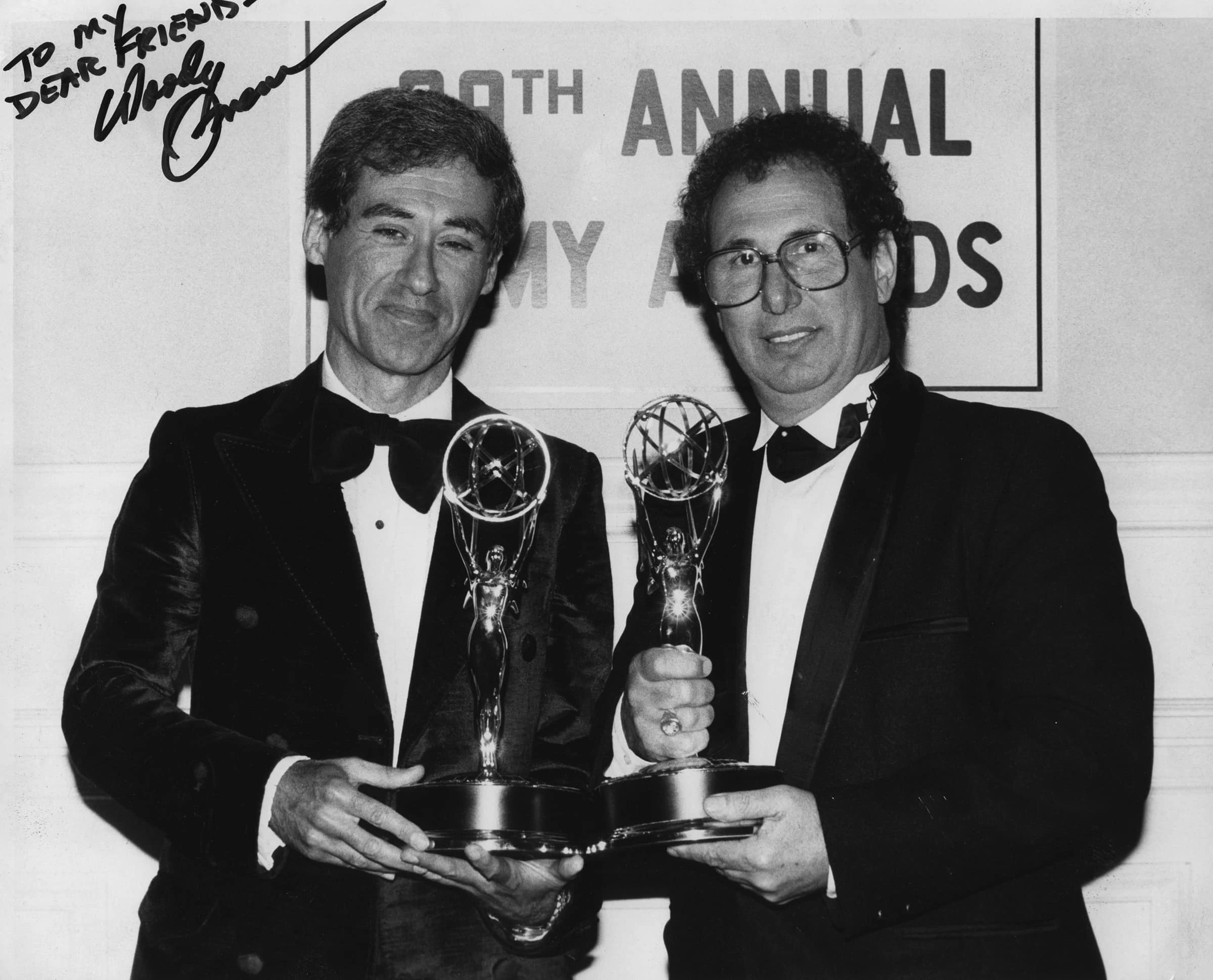

A pioneer who helped to change the face of network television by challenging creative conventions, George Spiro Dibie, ASC earned five Emmy Awards and seven additional nominations for multi-camera, episodic television series between 1985 and 1998. His award-winning programs were Mr. Belvedere (1985), Growing Pains (1987 and 1991), Just the Ten of Us (1990) and Sister, Sister (1995). The other nominations were for Night Court (1986 and 1988), Growing Pains (1992), Dudley (1993) and Sister, Sister (1996, 1997, and 1998).

He died on February 8, 2022, at home, surrounded by family, following a long illness.

“George Dibie broke all the rules because he understood that there can be drama in comedy, and comedy in drama,” said Russ Alsobrook, chairman of the ASC Award Committee when the cinematographer was honored with the 2008 American Society of Cinematographers Career Achievement in Television Award. “He ignored the broadcast engineers mandate to make all multi-camera shows look bright. George knew how to photograph beautiful actresses but he didn’t hesitate to use darkness and create gritty images when that was the right visual grammar.”

Dibie compiled between 1,500 and 2,000 hours of situation comedy credits on primetime television. He also shot between 60 and 70 television movies, including a number of programs for a regular, late-evening drama series called The ABC Armchair Mysteries.

“George earned this tribute from his peers in recognition of his artistry as a cinematographer,” said then-ASC President Daryn Okada. “I would be remiss if I didn’t mention that he overcame daunting odds to achieve a seemingly impossible dream. George has also dedicated himself to helping many other people achieve their dreams.”

Dibie was born on November 15, 1931 in Jerusalem, in Palestine, before Israel was a nation. “My father came from Corfu in Greece to visit the Holy Land,” he explained to American Cinematographer. “My mother came from Beirut, also to visit the Holy Land. They met, got married and stayed in Palestine. My father was a government health inspector in Jerusalem.

“My mother’s language was Lebanese. I also spoke a little Hebrew, as well as French, Italian and Latin, because I attended Roman Catholic schools. I also learned some English.”

A dedicated movie fan, Dibie was an avid still photographer during his youth: “Every Sunday, I’d go to church and then I’d use the money I earned by running errands for my parents to see movies. During vacations, I’d go to the cinema from 8:30 in the morning until 7:00 in the evening. When I was 8 or 9 years old, I cut cartoons out of a magazine and glued them together into reels. I built a small tent in our backyard and turned a shoebox and a flashlight into a projector. I made up and told stories about the cartoons and charged relatives, neighbors and friends a nickel each to see my ‘shoebox movies.’

“We had a Rolleicord camera with 120-format roll film. I took pictures of my family and friends, and later of trees and landscapes. Later, when I was in high school, I took black-and-white pictures at proms and was paid 5 cents for each roll of film I shot.”

Asked if there was a specific film that made an impression on him as a youth, Dibie told AC, “I remember very vividly the film Les Misérables, starring Fredric March [and shot by Gregg Toland, ASC]. That film encouraged me later in life to fight for the underprivileged among us, and maybe that’s what drove me to later be very active in the cinematographers’ union.”

“I’ve also never been reluctant to work harder than the next guy. That helped me overcome all handicaps, including having a strong accent and no connections in the film industry. I never gave up or allowed myself to become discouraged.”

After completing high school, Dibie was hired by the United States Information Agency (USIA) in Amman, Jordan. His job was translating reports written by members of the army in Jordan. One day, Dibie told his boss that his dream was to go to school in the United States and become a director or cinematographer in Hollywood. Seven days later, he had a USIA scholarship and was on his way to Los Angeles.

Dibie enrolled in a film studies program at the Pasadena Playhouse, where he focused on lighting and directing stage plays. “It wasn’t just teachers talking,” he said of the program. “I learned how to light and direct plays. Dustin Hoffman was one of the student actors. I remember a teacher telling him to look for another line of work. My thesis project was directing an original play called The Wild Harp. It was about the last four days of Jimmy Dean’s life. We played to a full house twice in one night, because they sold so many tickets. It also got a very good review, but I decided directing theater wasn’t my future.”

Dibie supported himself by working as a waiter and busboy. He also bought a couple of Bolex 16mm cameras and an Auricon projector, and shot films of weddings, bar mitzvahs and other events.

How did he cope with being on his own in a foreign country, trying to break into an industry what was a relatively closed to outsiders? “When I lived in Jerusalem, I met people who told me stories about how they made it through the Holocaust,” Dibie remembered. “My challenges were child’s play compared to that. I’ve also never been reluctant to work harder than the next guy. That helped me overcome all handicaps, including having a strong accent and no connections in the film industry. I never gave up or allowed myself to become discouraged.”

After Dibie graduated in 1963, he worked as a checker in a supermarket, where he shared his dream with shoppers. One of those customers worked for 20th Century Fox, and called one night to tell him to report on the studio lot for work as a day player on an electrical crew the next morning.

His first day on the job was on a set where Leon Shamroy, ASC was filming the lavish Fox production of Cleopatra. Over time, he worked his way up through the ranks, becoming a best boy and then a gaffer, serving on crews with legendary cinematographers including ASC members Harry Stradling, James Wong Howe, Harkness Smith, Howard Schwartz, Jack Marta, Harold Stein and Philip Lathrop.

“I learned so much by watching and listening to them,” Dibie recalled. “I was Harry Stradling’s gaffer when he shot On a Clear Day, starring Barbra Streisand. She was beautiful. I invented the ‘Stri-light’ for her. Barbra really knows how to find her light. One of the most important things I learned by watching Harry was how to light people’s eyes to reveal their souls.”

He also received sage advice from Howe: “I never forgot him telling me, ‘Don’t screw with your negative.’ He did not believe in putting a diffusion glass that costs a few dollars over a lens that had cost thousands. He also said, ‘We never make mistakes.’”

In 1966, Dibie and Dr. Roger Dash organized Dibie-Dash Productions — a company for the purpose of shooting and distributing 16mm documentaries and educational films. Dr. Dash researched and wrote the scripts. Dibie directed, shot and edited the films. “Our first film was They Beat the Odds,” Dibie said. “It was a 22-minute film with real stories about six black people who grew up in the ghetto and succeeded in life. We intended to rent it to high schools. We showed it to some PhDs on the Los Angeles Board of Education. One of them told us, ‘Black people don’t think like that.’ That made me pretty angry because Dr. Roger Dash happened to be a black person. He knew more about this issue than all of them put together. But, we found other customers, including NBC and Pepsi Cola. They bought hundreds of copies of our film and showed them to employees.” Dibie-Dash created and distributed 20 films over the following years.

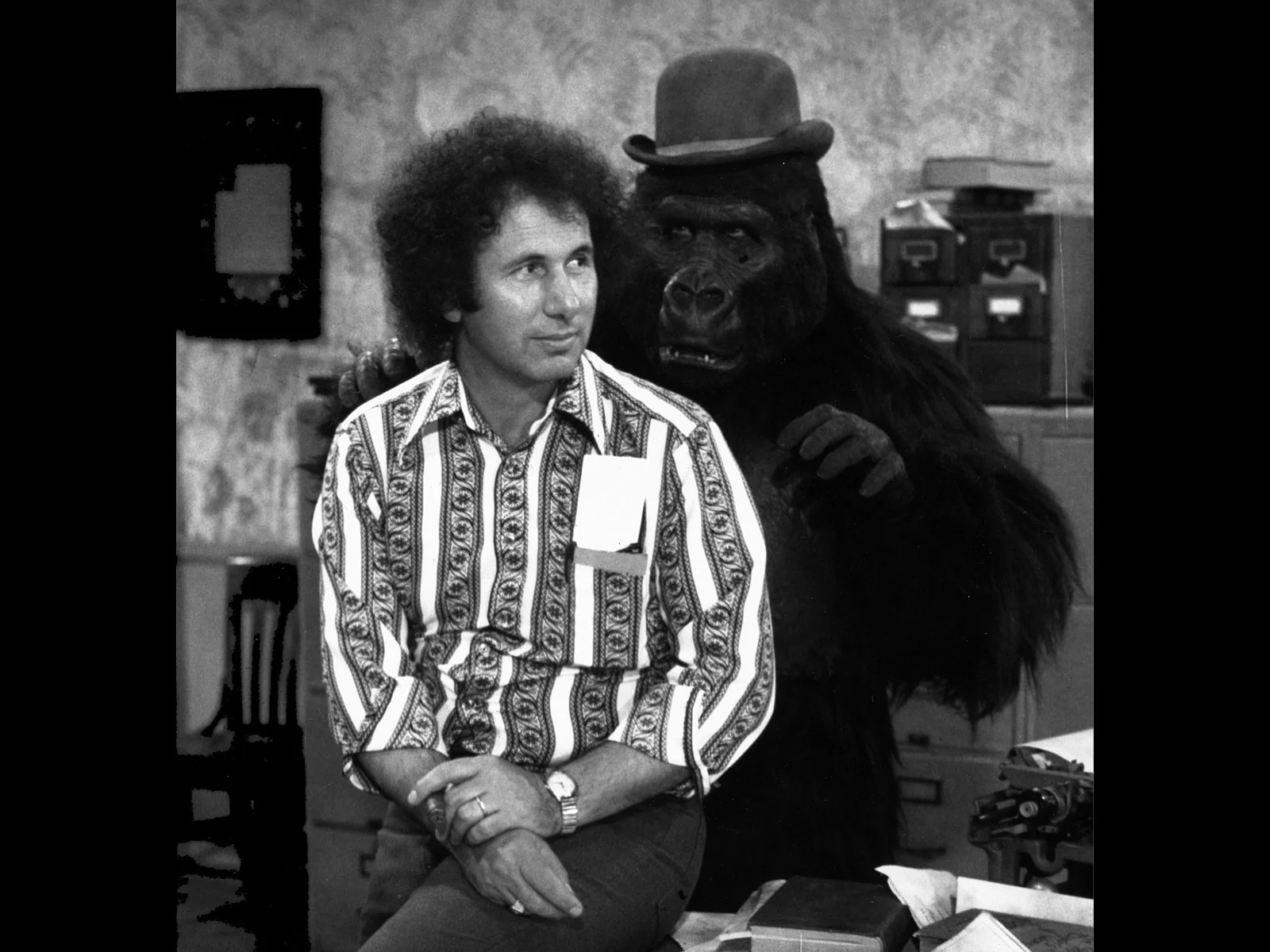

Dibie’s first break in Hollywood was a humble one: “Warner Bros. needed someone to shoot a multi-camera video children’s show called New Zoo Review in 1972. Nobody in the Guild was interested in shooting video. Someone at a lighting rental company told someone at the studio about me. It was ironic because all of my experience as a cinematographer was shooting 16mm film. But New Zoo Review led to my next job.”

That would become his big break.

In 1975, executive producer Danny Arnold recruited Dibie to be the director of photography for the ABC network series Barney Miller. A smart 30-minute situation comedy set in a police precinct headquarters, the show starring Hal Linden, Abe Vigoda and an ensemble cast. The pilot had been shot on film, but the series would be produced with multiple cameras in video format. “Someone told Danny that I was a video guy, because I shot New Zoo Review,” Dibie explained to AC.

“In those days, video shows had technical directors who looked at wave form monitors in the control booth, and made sure that the key-to-fill light ratio was 2:1, which was SMPTE standard,” he recalled. “It was a broadcast standard that the engineers wrote because they believed all video programs needed a bright look like game shows. Danny told me that he wanted a dramatic look that was right for the mood and environments where scenes were happening. If it was supposed to be dark and moody, he wanted that look.

“I had a lighting director instead of a gaffer. He was used to working on game shows and other live TV programs. The first thing he said was that the stage demanded 250 footcandles of key light. I made a little joke and said, as soon as you leave, I’ll talk to the stage and we’ll convince it that we only need 50 footcandles. We used very source-y light. I was told that two video controllers refused to work with me, because I was shooting scenes at T3.5 wide open. They had been taught that all video shows were shot at T5.6. They complained that the pictures were noisy, which is the video equivalent of grain. They went to Danny Arnold and complained about me. They said I was watching everything they did, and insisting that they adjust colors. Danny listened and then he said, ‘That’s why I hired him.’ They also complained about the noise, and Danny said that’s what a New York police station is supposed to be like.

“We had scenes at police headquarters sets at all hours. We wanted it to be dark at times, and other times there was sunlight coming through windows. There was a show where we put cigarette butts and trash on the floor, because we wanted a down-and-dirty look. I remember coming in the next morning and finding out somebody had cleaned the set and mopped the floor. We had to make the place dirty and throw cigarette butts on the floor again. My point is that it was a comedy, but we were still telling a story. The more realistic it looked, the more people accepted the characters and their jokes. After a while, the crew was making jokes about the cartoon lighting on other multi-camera shows.”

Funny, but often featuring a dramatic edge, Barney Miller became a fan favorite with an eight-year run on television, but Dibie re-fought the same battle with television engineers on various other programs. For a number of years, the camera guild rules limited Dibie to working on multi-camera TV programs produced in video format. He challenged that rule and broke through that barrier in 1983 when he shot the multi-camera episodic series Buffalo Bill on film.

Dibie earned his first Emmy Award in 1985, for the Mr. Belvedere episode “Strangers in the Night.” The script’s blend of comedy and drama again had Dibie challenging conventions and expectations. As the cinematographer remembered, “We were rehearsing a night scene with Christopher Hewett, who played the title role in Mr. Belvedere. He was standing in the shadows of his darkened living room until the beam of a flashlight revealed his face. A voice ordered us to bring the lights up so the audience could see Chris. It was the technical director, who was sitting in the control booth talking over a loudspeaker. I asked, ‘What’s the point of writing a night scene if you make me light it like a daytime scene?’ Chris also spoke up and so did the director. We won that battle. There is comedy in drama, and drama in comedy. That is the way the script for that scene was written. I believe in actors. Without them, none of us would have jobs. They aren’t paid to hit marks. They are paid to perform and follow their instincts.”

At the time, there were three different Locals representing cinematographers and camera crews in the United States. They had organized in 1928. The Local in New York represented members on the East Coast. The Local in Chicago represented members in the Midwestern states. The Los Angeles Local represented members of the West Coast.

Frank Stanley, ASC, president of the Los Angeles Local, encouraged Dibie to run for second vice president in 1984. He was elected and stepped up to president after Stanley retired because of a health issue. Dibie was re-elected in 1985. He served as president for 20 consecutive years. During that period, the three regional organizations were merged into the International Cinematographers Guild, Local 600.

Dibie is credited with initiating a diversity program designed to assist women and other under-represented people in the industry, and to help them succeed as cinematographers and camera crewmembers. He also supported a plethora of training programs designed to enable members to nurture their talents and skills.

Back behind the camera, Dibie shot every pilot that was made by Warner Bros. for 10 years while under contract to the studio, including My Sister Sam, Head of the Class, Murphy Brown, Driving Miss Daisy and The Trouble With Larry. And while proud of his body of work, Dibie never took the time to accurately tabulate how many hundreds of episodes and thousands of hours of network programming he photographed. “I know that I have half-a-dozen souvenir T shirts from shows that went over 100 episodes,” he said with a smile. “I would guess that I have shot something between 2,000 and 3,000 episodes of series, and between 10 and 20 pilots for other successful shows. If you put those hours back-to-back, it is the equivalent of shooting between 150 and 200 movies.”

In addition to his tenure as the president of Local 600, Dibie was also an active member of the Directors Guild of America, the Technology Council of the Motion Picture Television Industries, the Society of Motion Picture and Television Engineers, Education Committee (AT AS) and UCLA Extension Cinematography Advisory Committee.

Recommended by ASC members Haskell Wexler, Harry Stradling and George Koblasa, Dibie was invited to become an active member of the Society in 1994. “I am one person that should thank the gods for my good fortune in my career and family life,” Dibie told AC when asked about this honor. “I worked very hard to be where I am today. Belonging to the ASC means you are a part of a distinguished group of artists who strive for excellence in the art of cinematography.”

Dibie would spend countless hours serving the Society as a member of the ASC Board of Governors and as chair of the Education & Outreach committee, with the mission of offering free events to emerging filmmakers and industry professionals in an effort to promote greater understanding of the cinematographer’s craft. With the participation of numerous volunteer ASC members, these events — entitled “Dialogue with ASC Cinematographers” — were informal Q&A panel affairs often held at the ASC Clubhouse, attended by student groups from major university-level film programs from around the world. The open, candid exchange of information and experience from established cinematographers was invaluable to these aspiring artists.

ollowing brief introductions of the panelists, Dibie immediately asked for questions from the audience. “We’re there to honestly answer their questions, with no agenda or bias,” he said. “We just give them the truth; the reality of what it is to build a career, assemble a crew, collaborate on the set and — most importantly — to understand that everything cinematographers do is about understanding and telling the story visually. It can be a feature film or TV series or commercial or any other motion picture project. Everything we do — lighting, compositions, camera angles — has to be about the story.”

Students benefitting from this in-person interaction arrived from such schools as Loyola Marymount University, Tulane University, College of Southern Nevada, Queensland University of Technology (Australia), California State University-Fullerton, California State University-Northridge, UC Los Angeles, UC San Diego, George Washington University, New York University, San Francisco State University and Compass College of Cinematic Arts.

“The experience and knowledge we have gained over many years of hard work on the set is what we’re offering them,” Dibie explained. “You can’t learn that from any book or by studying films, whether it is regarding the creative process or working relationships.”

Dibie also conducted his “Dialogue” events at film festivals and major industry trade shows, including NAB and Cine Gear, drawing standing-room-only attendance.

What did Dibie tell young and aspiring cinematographers asking him for the secret of success? “I ask them what they think the odds were when I was growing up in Palestine that I’d end up working as a cinematographer in Hollywood. You have to persevere. It takes talent, a desire to keep learning, and a willingness to work very hard. I tell them to get as much experience as they can, doing everything they can. You can learn by working with and watching more experienced cinematographers. It’s not just about learning how to expose film, focus and operate a camera. You also have to learn about set etiquette and attitudes, and how to talk to people so they listen and cooperate. I tell them to get on sets and watch how cinematographers they admire work with the gaffer, grips, the boom guy, make-up and hair people and everyone else. I also encourage them to shoot every chance they get, including free films for students.”

Participating in a seminar for film students and other aspiring filmmakers, Dibie was asked how he kept his spirits up when things were difficult. He replied, “That’s simple. I love the work. You are helping the director, writer and producers create a fantasy world. You read a script and start to dream about what it should look like as you tell the story. To me, that is like painting, and I love to paint. This was my boyhood dream and it has all came true.”

In that, Dibie leaves behind a rich legacy not only evidenced by his numerous credits and awards, but the many careers he helped inspire.

With invaluable reporting by Bob Fisher and Jon Silberg.

–