Home » Features » Interviews » Visionary »

INSPIRING THE INDUSTRY

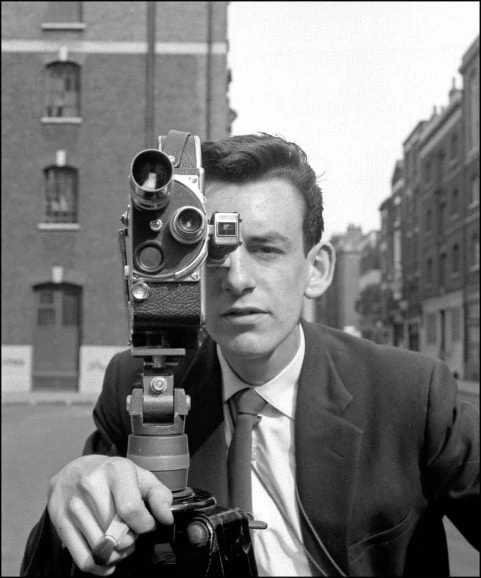

From Scum and The Long Good Friday through to The Mask of Zorro and Casino Royale, award-winning cinematographer Phil Méheux BSC has entertained and inspired many with his work. An early fascination with filmmaking led him to embark on a career at the BBC, honing his craft shooting documentaries and television plays. After making the move into feature film, Méheux enjoyed many successful production partnerships with directors such as John Mackenzie (The Long Good Friday, The Fourth Protocol) and a two-decade long partnership with Martin Campbell (Criminal Law, Beyond Borders, GoldenEye, Casino Royale).

In 2015, he was awarded the ASC’s International Award and following this year’s BSC Awards night, the former BSC President and member of the BSC board since 1999 can now add a Lifetime Achievement Award to his accolades. We felt it only fitting that James Friend BSC ASC – whom Méheux mentored and has formed a firm friendship with – sit down with the filmmaking master to discuss his career and gain an insight into the industry and art of cinematography.

James Friend: Let’s start at the beginning of your illustrious career. How did you first become fascinated with cinema?

Phil Méheux BSC: When I was five, my grandmother took me to a pantomime on ice. I remember being captivated by the dubbing box and follow spots. I thought ‘I’d like that job.’ So, I became interested in entertainment from a ‘behind the scenes’ point of view. I was fascinated by how it was put together and how all these people came together to make an entertaining extravaganza. Shortly after I was taken to the cinema to see Bambi. I remember it vividly – I was totally entranced by the sensation of the cinema, as so many children are.

In my youth, I lived in Canvey Island, which was a working-class seaside resort, and in the summer, this giant bus with blacked out windows and a back projection screen visited the seafront. They screened 16mm black-and-white silent comedy films like Charlie Chaplin and Felix the Cat for threepence a go and I’d go many times. When we moved back to Sidcup, I’d visit the cinema regularly to see the great Hollywood films of the late ‘40s and ‘50s on the big screen just as CinemaScope was invented. It got to a point where I started keeping a book of the names of the directors of photography of the films I saw. Every Christmas I’d also receive books about films or filmmaking and drooled over behind-the-scenes photographs of cinematographers sitting on the camera crane. I wanted to be that person.

When we got our first nine-inch black-and-white television set for the Queen’s Coronation in 1953, it didn’t captivate me in the same way.

JF: The illusionist aspect of it and the technical black art is more public today. However, it still fascinates people, doesn’t it?

PM: Yes, it does. It’s what made all of us who became cinematographers so passionate about it. The passion has dimmed a little in terms of how it’s used, and how you’re treated as a cog in a machine rather than somebody who’s creating images. That’s the tragedy, but it’s inevitable in many ways. Painting, music, writing novels have never gone that way. It’s just cinema that has become this industry. I’m sure if you go to any film company office, there’s probably a pile of excellent scripts, which are not being made for all sorts of strange financial reasons. It’s a great shame.

When I was a child, cinema was among the most important entertainment outlets and films were much in demand. MGM at its peak was making a film a week and now that’s dropped because of the economic problems surrounding it and because this is an industry which has to sell its wares. Director Jean Cocteau once said, “Filmmaking will never be art until it’s as cheap as pencil and paper.” I think there’s a lot of sense in that. It’s become too expensive now. To get a crew for one day on a feature, you’re talking thousands of pounds.

JF: Can you share some insight into your formative years at school?

PM: The difficulty I had at school was that I was brighter than people of my own age, so I was put up one level up which meant I couldn’t be top of the class anymore. That made me a bit of loner at school, but I did very well because I concentrated on the work. I didn’t find anyone at school who was interested in cinema at all, but I was determined to do it.

When the careers adviser asked me what I was interested in, I didn’t dare say filmmaking. I said photography. He replied, “Oh no, you don’t want to do that. They’re all freelance and don’t know where the next job’s coming from.” I didn’t see a problem with that. He suggested a job for me – clerk at the London Docks. But that wasn’t the job I wanted and thanks to my mother I didn’t take it because she said, “If you don’t want to do it, don’t do it.”

My mother and I then saw an advert in The Evening News for a clerk at a film company.’ My mother called them up as they were local, and we went to the MGM sales department. I filled out the form and the lady at the desk said I could start the following week. That company was a major turning point for me as I was introduced to Mike Appelt, a clerk like me, who had his own cinema room in his house. He and his friends, twins Malcolm and Alan Johnson, put on a show for me with an old sound newsreel and a silent film called Sponge Fishing which they accompanied with Ravel’s Boléro on the gramophone. It was fantastic. As the friendship developed, we started to rent 16mm prints of all the classics and Malcolm introduced me to foreign cinema. We then thought we’d make our own film, bought a second-hand Eyemo clockwork camera, and started to make a film based on the piece of music, London Fantasia, written by Clive Richardson. We could only do it on Sundays with a 100-foot roll of black-and-white film, so it didn’t proceed very fast.

JF: With a crew of four people?

PM: Yes, we took turns to do each job. I seemed to be very good at the camera, Malcolm was good at directing, Michael at organising everything and producing, and Alan was interested in sound, but we couldn’t afford any sound equipment, so he’d come along for the fun of it. We bought a simple home movie editing viewer and a splicer to cut it all together and built our own rewind table. I started cutting the footage together and became the cinematographer and the editor. So, that was my film school. We made almost one film a year. Sadly, we always stumbled at the end because we had no way to do sound and couldn’t afford professional help.

I then got a job with an advertising agency as the librarian/projectionist because all commercials in those days were made on 35mm film and I used to have to keep a stock of the ones that were current. My job was to order them and deliver them to the different television houses. They had a preview theatre which had a 35mm double head projector, a 16mm sound projector, a tape recorder and microphone, and editing equipment. So as amateur filmmakers, we’d meet there at the end of the day and screen things, cut things, and talk, which furthered that filmmaking experience.

One day, we went to the Academy Cinema on Oxford Street to see John Cassavetes’ film Shadows which he’d made on 16mm black-and-white and had blown up to 35mm. We thought we could do that too. So, Malcolm wrote a script for a feature length film which was mostly visual. The budget we set was ridiculously small now that I look at it because I just budgeted for equipment, and then we went looking for people to invest. A furrier Michael knew said he’d put in £2,000 and we found somebody else to give the other £2,000. Malcolm and I gave up our jobs and set a start date and then the furrier died, and the other investor also pulled out so we were back to square one. This is so common in the film business we now know, but to us that was a shock because we were jobless.

I had to make some money, so I joined the Cameo Royal Charing Cross Road as second projectionist while we licked our wounds. I then applied for a BBC trainee assistant ‘film cameraman’ position that was featured in The Sunday Times. The traineeship was full, but they desperately needed a projectionist and they told me there may be another trainee scheme down the line. I jumped at it and joined the BBC in 1962. Brian Tufano BSC, Tony Pierce-Roberts BSC, Mike Southon BSC all started with the BBC Film Unit. The BBC was a wonderful place to help you move forward in your career.

JF: So that was a great stepping stone for you?

PM: Yes, I’d made a good name for myself. I understood the technology. Because of my experience, I was assigned a 35mm theatre with a projectionist who had come from Odeon Cinemas and we developed a technique for showing cutting copies without breaks because we worked out how to change from one reel to the other without any dots, which is how you do it normally. Master editor, Alan Tyrer, said, “I love your cinema. You do these wonderful changeovers; I get the feeling of the pace of the film.”

My friends and I were still making films of our own while I worked there. We made one called One is One and I was able to use the cutting rooms after hours at the BBC, so I laid seven tracks and recorded all the sounds in my bedroom and transferred them to magnetic tape. We didn’t have any money to do the final neg cut and the final dub and recording of the music, so we showed it to the British Film Institute Experimental Film Fund. The head of the fund was director Bruce Beresford who thought it was amazing and gave us the £150 quid we needed. It was on the strength of that I got into the BBC training scheme because I had photographs of me operating the ARRI ST camera.

JF: How long was the training scheme before you graduated as an assistant cameraman?

PM: I did the training scheme for the last few months of 1964. It was mostly classroom based and going out with crews to watch them work. I went out with the grand BSC member Tubby Englander on a night shoot in Frensham Ponds, something I’d never done in my life. Tubby said, “The first night, you can watch what we do. The second night, you can clap the clapper board. The third night, you can write the sheet on the back of the clapper board. And on the fourth night, you can load a magazine.” What great training that was because I wasn’t shoved into it, right at the top. I was allowed to develop bit by bit.

I was supposed to do that traineeship for a year, but later that year cameraman Dick Bush, who later became BSC, was supposed to shoot an episode of Spies but his assistant was ill. The manager of the camera department, a former Ealing Studios camera operator Hugh Wilson, told him he had two trainees he could choose from, and one of them was me. So having just been a trainee, I then found myself on the floor of a passenger bus, looking at the focus control on a blimped Arriflex in the Pennines using a dentist’s mirror. Talk about being thrust into it headfirst. Dick was a very interesting, inventive, and artistic person to work for.

JF: So how did you make the step up to become a cameraman?

PM: I was put with a cameraman who was shooting Dixon of Dock Green, one of the most successful and longest running police series the BBC ever made. Everything outdoors at night was shot on film. So, the cameraman said, “Why don’t you operate the camera, and I can get on with the lighting much quicker.” What an experience that was. Every night I went out, I was operating. It brought me further on in understanding how you put scenes together, construct a scene, vary the lens sizes, and choose the lens sizes.

And then with this cameraman, I got involved in a documentary about pop music and went all over the states filming The Animals, Jimi Hendrix, The Who, Pink Floyd. That taught me a lot about documentary work and how to piece those things together and gave me a lot of experience. When we came back to London the cameraman left the show and they had a meeting with film operation manager, Dave Ziegler, to decide what to do next. They offered the job to two other cinematographers who turned it down and then they asked me. So, I finished the documentary – All My Loving – for director Tony Palmer – which was quite successful, if controversial.

Having done that, and still an assistant, I was sent to a tabloid documentary programme, Man Alive, as a ‘holiday relief cameraman’. After a few months I was approved by producer Desmond Wilcox, we got on very well and they wanted to keep me on. The office said I was an assistant, so they couldn’t take me on until I was a cameraman. So, they put the job on the board, I applied, and got it, so I carried on working for Man Alive in 1968. It was there I met director James Clarke and we got on well. I found out he aspired to write and direct feature films. Then in 1972, he had an idea to make his own feature film, put his own money up, and get a crew together. James asked me to advise him because I knew a lot about filmmaking, so I joined him as a sort of producer and got a good insight into the other side of the business, which was quite useful. I had to find out what the fees were for everybody, the working hours, what the lunch allowance was, what the hotel fees were. The operator on the production was then fired and James asked if I could take on the role. I operated for the rest of that film as well as producing. I took leave of absence from the BBC to do that unpaid.

When I came back to the BBC, I felt, I needed a change as I aspired to make drama films. I carried on doing documentaries for a bit and then was shooting dramatic sequences for productions such as Love and Mr Lewisham, so I was getting feature type experience. In 1974, freelance director John Mackenzie came to me with a script by Peter McDougall. John and I did the scouting and prep for it and then the management of the BBC said the film was too politically contentious. The following year, it came around again, but they offered him another cameraman. John said, “I liked the one I had, and we’ve talked about the whole film.” So, I shot Just Another Saturday, which is the first full-length film, I’d done, and I thank John Mackenzie for having faith in me.

I then travelled on with the BBC and a couple of years later I shot another play with John called Elephant’s Graveyard, another very interesting script written by Peter McDougall. Following the transmission of that I got a call from director Anthony Simmons who asked if I was interested in shooting a low budget feature film in the same documentary style, handheld, using available light. I met him, he talked about the film and how they wanted to improvise and follow a documentary style.

But I wanted to do something with cranes, tracking, and big lights. This was documentary again and I wasn’t sure if it was right for me. I spoke to James Clarke’s wife Marita, who became a very good friend, and she said, “You always said if you got offered a feature film, you would do it. You’ve just been offered a feature film, do it.” So, I took it on and left the BBC at the end of 1976 and went freelance.

JF: Can you tell us about that first feature film? That was the start of a rather important filmmaking relationship for you, wasn’t it?

PM: And then when we went on to make Black Joy, I was introduced to the producer Martin Campbell. He’d directed a few low budget sex comedies and didn’t want to be typecast, so the director Tony Simmons suggested he produced for him. When I met Martin, and we discussed salary, he said he only had a certain amount. I agreed to that amount as it was more than I was earning and had no idea what the salary was for cinema. A week before we started shooting, he said he’d increase my money as he’d had that in the budget originally but didn’t think I would give in that easily. From that moment on we became friends. I had a great respect for him as some other people might have pocketed the difference.

JF: So that was one of your seminal moments?

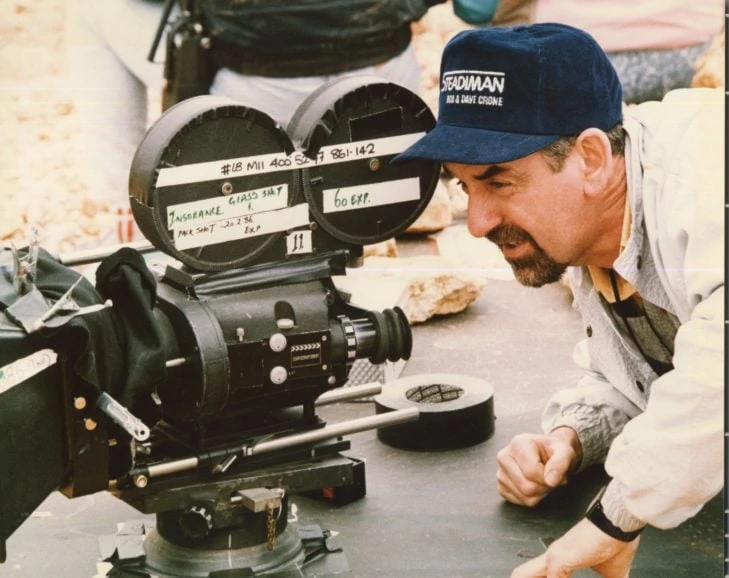

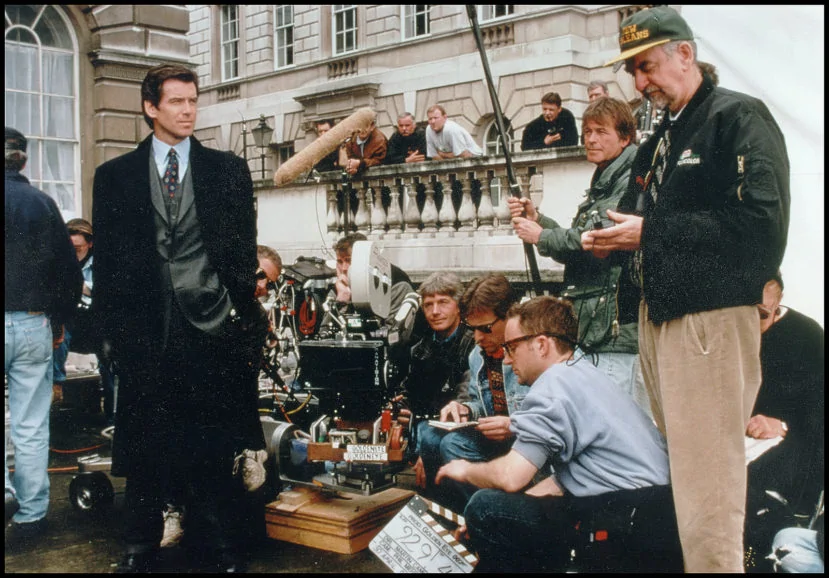

PM: Yes. After that, Martin Campbell was asked to produce Scum and brought me on as cinematographer. It was quite a successful film. He then told me he was going to concentrate on directing for television. In 1986, he directed the series Edge of Darkness, which won 10 BAFTA Awards, and got offered 20 film scripts. He chose Criminal Law and asked me to be the cinematographer. It’s a film I’m proud to have worked on. I operated as well, as I couldn’t find an experienced operator where we were shooting in Montreal, who first of all spoke English fluently and who lived up to what we wanted to do. Montreal is different now and a very successful film hub. I then went on to shoot nine more films with Martin, including GoldenEye and Casino Royale.

JF: What would you consider some of your highlights from your varied career?

PM: Getting the first full length drama film to shoot at BBC television was a career highlight, and it went on to win the Italia prize of the best single play of 1975. The last play I did for BBC television was Spend, Spend, Spend which was nominated for a television film cameraman award by BAFTA and won the Italia prize for best television play of 1977. Black Joy was another highlight, because it was the first feature film I shot. The next one was probably The Long Good Friday. And just before I shot that I signed with agent Freddie Vale who approached the board at the BSC in 1979 to put me forward for BSC membership which amazingly they approved.

JF: And moving onto the importance of mentoring, I was very proud to have been mentored by you and now we’re dear friends. Were you mentored?

PM: No, it wasn’t considered a thing to do in my day. Your mentors were people you knew. A mentor is the person you can always rely on to give you information. In my day, you might talk to someone who’d worked on a film as an operator and ask how they got on with a director. That’s a form of mentoring. It’s good to have someone at the end of a phone or an email address if you get stuck and want some information. Mentoring can be very useful when you get to know each other. You get to know how the person you’re mentoring works, what they know and don’t know, and they get to know what you’ve done. It establishes a much more useful relationship and hopefully you become friends and have dinners and lunches and talk about the business.

JF: So, you would encourage young up-and-coming cinematographers to seek out a mentor? We had that relationship and then you proposed me for membership to the society. I’ll never forget the day I got my certificate, and I was leaving the venue and Gavin Finney BSC pulled me aside and said the ethos of the society is that we all have each other’s details and don’t hesitate to contact each other. A year later, I was shooting in Scotland, and I knew Gavin had recently shot there, so I phoned him for crew and recommendations. Could you talk a bit about the BSC, how it is structured, and how you’ve benefited from being part of a society?

PM: Becoming a BSC member is a career highlight because the society is made up of people who do what you do, and they do it very well. They also appreciate your work and consider you one of them. That in itself is a tremendous accolade – that Freddie Young and Ossie Morris turned around and said, “Yeah, you can be a member.”

I was bowled over when I was accepted into the BSC because I was a young whippersnapper and had none of the experience the other people had. In the beginning of my membership, I didn’t go to many of the social gatherings, because I was in awe of people like Freddie Young OBE BSC, Ossie Morris OBE BSC AFC DFC, Bob Krasker BSC ASC, all those giants of cinematography. I thought, ‘I can’t stand in a room and speak on equal terms, I’ll be a blithering idiot.’ I steered around it until eventually, I got asked to be on the board in 1999. I then got into it much more and realised what I’d been missing. So, I got to meet those giants.

The BSC is a collection of people who have the same approach, enthusiasm, and passion for the job. I talked to Billy Williams at one point about working in Mexico because I was about to do it for the first time. He gave me some really useful information. That’s what’s great about the BSC. And that’s what mentoring should be about – helping people when they get to a stumbling block, or they’re not quite sure which path to take, and you can help.

I once asked a cameraman I worked with at the BBC why he hadn’t done a feature film yet? He said he couldn’t find the right one. So, I said I thought he was being silly, you need to take any feature film that’s offered to you because once you do you get a reputation for being able to deal with it. That alone is a recommendation. You’ve just got to get out there, do as much as you can and in as many different areas. And don’t look down on the work if you’re being paid to look through the camera and make it look good. As you get more established, you can be a little bit more selective, but I would still be careful about turning anything down because you don’t want to get a reputation for being fussy.

We all do commercials now too. I never shot a commercial until I left the BBC and then suddenly, I found this whole world of commercial making where you could try things out, learn from other crew members, and get more time to find out how different directors work and how best to tackle a shot. The tragedy with modern filmmaking is that as a DP, you have to turn up on the set or the location, deliver the goods in the time allowed, and the equipment you have and then walk away. Everybody else gets a second go, the director, editor, the costume supervisor, the CGI team can redo an effect. As DPs we don’t get any time to try anything while we’re doing the job. You’ve got to go in totally prepared. It’s the one job in the film industry where you can’t do it again. The DP must be on their toes all the time. And that’s what up-and-coming cinematographers need to realise – it’s not a game, it’s a business and you must be prepared every day, because there’s a lot of money at stake.

JF: And you were president of the society while you were shooting Casino Royale, weren’t you? That’s quite a lot to take on.

PM: I would find it difficult to understand if anyone said they could not answer an email when they’re shooting. You are saying you have no time in the day when you can’t say yes or no to an email. It’s part of your job as a board member or president. If you care about the BSC, you want to be a member of the BSC and have the letters after your name, you must respect the society, what it stands for, and what your involvement is with the society. It’s not just about putting someone on a pedestal and saying they’re approved. It’s about you wanting to be part of this communal society. You are revered as a member, and you must take an interest in what the society does and how it moves forward.

JF: What was your reaction to receiving the BSC Lifetime Achievement Award?

PM: I am touched and totally honoured that the board decided they wanted to award me. It’s an outstanding career moment. I’d like to think it’s partly to do with the work I’ve done for the BSC. Now you and I, James, have compiled a book of members and the history of the BSC called Preserving the Vision. We’ve worked on that for two years, almost every day.

JF: Could you talk a bit about the book, what it represents, and our reasoning for wanting to preserve the vision and the history, and celebrate the heritage?

PM: In the first lockdown, you thought it might be a good time to compile a book of all BSC members since its inception in January 1949. I was very interested to get involved, because a lot of the time I’m compiling obituaries, sadly, for those people who have left us to include in the newsletters. I also have many books written by BSC members that I refer to. I thought it sounded great – James could focus on the newer people, and I could write about the departed cinematographers, and it would make a great book. The idea grew from there – to incorporate the history of the BSC, how it started, and what it does now. It also evolved to list the awards that BSC members have accrued, including the three major awards, the Oscar, the BAFTA, and the BSC Award. It’s been a hell of a task putting the book together and has taken almost 2 years.

JF: What are the most important lessons you’ve learned which might be helpful to those looking to become a cinematographer? And is there any advice you would you say to your younger self if you had the opportunity?

PM: One of the most important lessons I learned is don’t look down on the work. You need the work to establish your position and to learn your craft. You’re not going to enter the business as an Academy Award-winning cinematographer straight away, even though in your mind you think you could. Rachel Morrison ASC was the first woman to be nominated for an Oscar which is terrific news. But she wasn’t new to the job. You need that experience, you need practice to know how the business works, so you can tailor it to your needs.

My advice to young people is don’t turn the work down and do everything you can. Just keep doing it because that’s how you learn and how you build your style. One piece of advice I was given by Dick Bush was, ‘If you don’t think a shot is quite right, just do anything. Take the camera up a foot, move it left a foot. Don’t think you’re stuck with it. Just keep thinking how you can improve what you’re doing, always bearing in mind that telling the story is everything.’

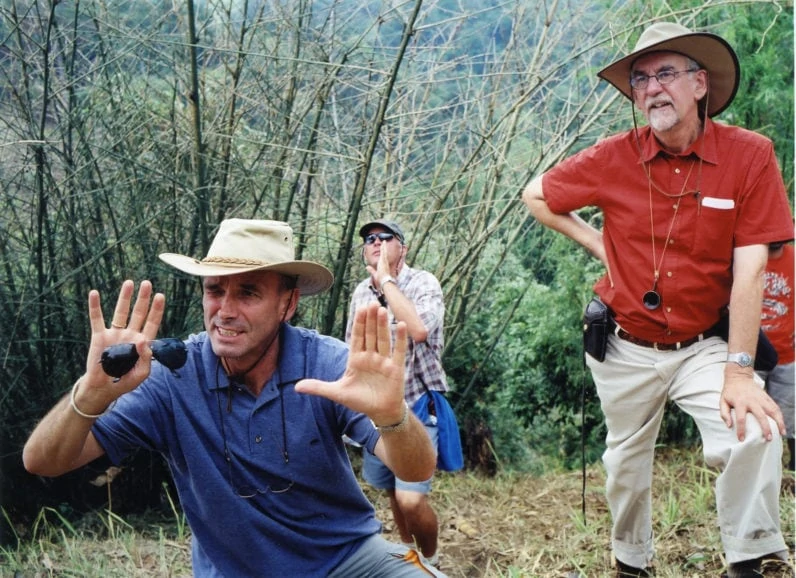

Preparation is everything and this is something I talk to students about. First you read the script and make a note of everything in it that will affect the photography and listen to the director and how they see their film. And then when you go on location scout, bear those things in mind. Make a plan – what I call a Bible of the whole film – scene by scene, sequence by sequence, and turn up on the day knowing how you’re going to do it. Most production managers fear the amount of equipment you’re going to need and not use, so it’s good to be prepared and know how many days you’ll need a certain piece of equipment. Look at the set drawings and understand what they mean in terms of tracking through a doorway, going up stairs, where the light is going to come from.

The other important thing is not to be full of yourself. Listen and learn. Also be aware that the director is in charge. They may ask for your opinion, in which case, you can freely give it, but the director must have control. It’s not your film, it’s theirs. Also, be aware that you’re capturing a story. The film isn’t a showcase of your cinematography or to show how flashy and clever you are. Some of the most successful films would not win a cinematography Oscar, but they serve the purpose of telling the story.

Most stories also rely on actors. And in fact, most stories nowadays rely on dialogue. The film is not about your photography, but don’t feel disappointed by this. Revere the actors’ faces as they are telling the story. Light them properly, and in a way that they look best. If you can’t see their eyes, you’re losing half of their performance. For example, in the film Casablanca there’s a head and shoulders shot of Ingrid Bergman, listening to the pianist play “As Time Goes By” remembering a love affair. It is a head and shoulders close-up and the camera doesn’t move neither does she, but the whole history of her love affair with Humphrey Bogart’s character is painted in front of you. That is performance and that is cinema.

JF: In my opinion, young cinematographers can get caught up in the technical aspects, how many Ks and so on. How important is it to stay up to speed and how has technology changed over the years?

PM: When I began in the business, I started shooting black-and-white film on a 16mm EYEMO camera – a wind-up camera designed for combat use during the war which survived afterwards. It’s a beautiful camera. As time went on we bought a second hand Bolex H.16 but for our most ambitious film we rented an ARRI ST – the 100-foot loader where you take the top off and put a magazine on top. That’s how I shot films for the first eight years of my filmmaking as an amateur. When I became a BBC camera assistant, I then got to work as a clapper loader with a blimped Mitchell with a side finder, shooting black-and-white 35mm and I had to load those magazines. Newer cameras came along, and particularly the Éclair NPR, the Arrilfex 16mm BL and then the 35mm Arriflex 35BL. That changed how the business works. So inevitably, in a technological business, things are going to keep changing and improving. When the Panaflex came along, designed by Panavision founder Robert Gottschalk, that was a major improvement from the Mitchell. It was 35mm, you could hand hold it, and it was very slimline and efficient.

Before digital capture, the most important change for me in modern technology was the invention of the digital Intermediate, which meant you scanned your negative into a computer and then using computers, you could grade individual frames of a film and change the colour or graduation of parts of the frame. That gave us the advantage of outputting a fresh negative based on the input, so we didn’t have to make a copy of the negative and then lose quality, we could use, in effect, an original negative.

Inevitably, the downside of new technology is that when using any modern digital camera, you push the button, and the picture is almost perfect. Very often you can shoot with available light. That’s meant the expertise of lighting and controlling an image is leaving us. It’s being undermined. And with DI, the fact you could go into a suite, and grade your film a frame at a time has meant that directors have sometimes done it for the cinematographer or overridden the cinematographer’s wishes and made the film look as they want it to look, not as the cinematographer wants it to look. Not all together encouraging.

Now everyone is also racing to get the most pixels in an image. Every pore, every wrinkle, every hair can now be recorded and displayed on an 80-foot-wide cinema screen. That to me is not a good idea. It’s too sharp now. We watched films at the cinema in our youth and thoroughly enjoyed them. Why do we need everything to be surgery sharp now?

We also have the problem that the director takes iPhone photographs and home videos, which are pin sharp all the time. So, when they come onto the set, the focus puller looks uncomfortable because they are supposed to get it pin sharp at all times and often, they haven’t seen what the actors are going to do because the director likes to ‘shoot the rehearsal’. The focus puller is one of the most important roles on a film set. You can’t really use a shot that is not in focus where it needs to be and that is something that all training cinematographers must understand when choosing lenses and setting light levels.

When I started shooting, colour film was 50 ASA. Now, the standard basic rating of the Alexa is 800 ASA. That’s 15 times more light than I had to use when I started out. That can take away the expertise and the artistry of lighting at those apertures. Some modern cinematographers want the new, wide open, anamorphic lenses and the new fast cameras, so they can shoot with as little light as possible. But does that make the story work better? To my mind, that is doubtful.

JF: How have you seen the industry develop during your career? What are your hopes for the future of the industry?

PM: I think the major thing that’s happened to our business is the predominance of television and streaming now. Yes, the quality has got so much better over the years, but some of the skill and artistry has been lost. When you look back to photographer Ansel Adams, he got up at dawn to climb to the top of a mountain, fixed his camera on his tripod, and sat there until the light was exactly what he wanted. He took the shot and would spend three or four days making the picture look good in his processing room. Now, you click an app in your iPhone to make it look warm or make it look like a music video. You’re not doing anything. This lessens the value of the DP.

That’s the problem with modern cinema too. Cinema is an art form and we spent years perfecting it. The cinema was a meeting place of people where you saw a comedy film and roared with laughter with your friends. You enjoyed it so much more because you’re all laughing together. Now people sit by themselves and watch streaming films and shows. We’re losing what cinema meant and I miss that. If you don’t have Disney+ or Apple+, you’re not going to see the film sometimes. Whereas when it was in your local cinema, everybody could go to see the film.

JF: Has being a filmmaker changed your viewing experience, for better or for worse? I got into the business because I adored cinema and the art of filmmaking and then when I started making films, it changed the way I looked at them. I would forensically look at the lighting, camera work, acting with a critical eye. Is that the same for you?

PM: I seem to have two brains. I’m able to watch it as a film, but I do take note of what’s going on technically. So, if it’s badly lit, but a good film, I don’t care. If it’s well-lit and a bad film, I think it’s a bad film. You’ve got to look at the film as an entity. As a filmmaker, I love it when you see something and wonder how they did it?

I taught myself photography. I got books about it and I learned by having my own stills camera and processing my own material. I learned about film speeds, apertures and light levels. You learn all that from doing it yourself and from looking at how films are made and what others are doing. At one time Freddie Francis BSC was asked how he learned his craft, he said, “By doing it!” Wise words!

The BSC book Preserving the Vision will be on sale at the BSC EXPO and can also be ordered direct from the BSC office by contacting helen@bscine.com. For more details on the book, Preserving the Vision, click here.

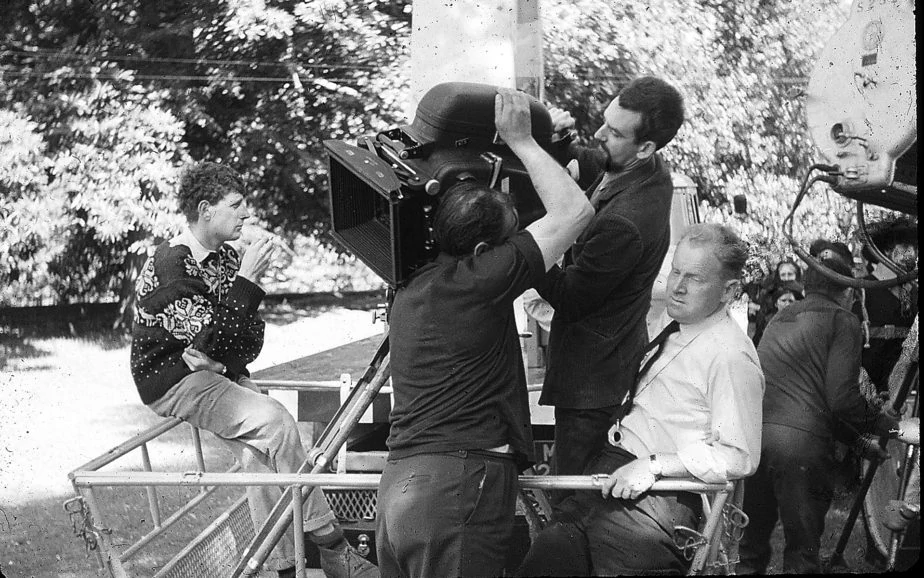

Mentor and mentee – and long-time friends – Phil Méheux BSC and James Friend ASC BSC (Credit: Richard Blanshard)