Sharp Shooter

Hoyte Van Hoytema FSF NSC / SPECTRE

Sharp Shooter

Hoyte Van Hoytema FSF NSC / SPECTRE

BY: Ron Prince

It’s always special when James Bond returns to the big screen. SPECTRE, the 24th movie in the ever-popular 007 franchise, features Daniel Craig in his fourth performance as Bond, taking on a chilling confrontation with an old adversary, not seen since Diamonds Are Forever (1971).

In the aftermath of Raoul Silva's attack on MI6 in Skyfall, a cryptic message sets in motion a series of events that force Bond to come face-to-face with the sinister global criminal agency SPECTRE (Special Executive for Counter-intelligence, Terrorism, Revenge & Extortion). Whilst the head of MI6, Gareth Mallory, fights political pressures threatening the future of the secret intelligence service, Bond discovers the only way to unravel the web of conspiracy is to protect the innocent daughter of his powerful enemy, and plunges into an adventuresome trail taking in London, Mexico, Italy, Austria and Morocco.

Christoph Waltz plays Franz Oberhauser, 007’s antagonist, with Léa Seydoux and Monica Bellucci the Bond beauties. Ralph Fiennes reprises his role as Mallory, the newly-appointed M, with Ben Whishaw as MI6 quartermaster Q, and Naomie Harris as Eve Moneypenny.

Produced by Eon Productions’ Michael G. Wilson and Barbara Broccoli, with a co-production credit for Craig, SPECTRE was directed by Sam Mendes, his second James Bond film following the record-breaking box-office smash Skyfall, lit by Roger Deakins CBE BSC ASC.

SPECTRE is reckoned to be the most expensive superspy film yet, with a reported price tag exceeding $300 million. Rumour has it that £24m worth of cars were written off in the making of the movie, including numerous Aston Martin DB10 coupés developed specially for the movie.

Ron Prince caught up with Dutch-Swedish cinematographer Hoyte van Hoytema, alumnus of the Polish National Filmschool in Lodz, and whose credits include Let The Right One In (2008), The Fighter (2010), Tinker Tailor Solider Spy (2011), Her (2013) and Interstellar (2014), to discover more about the whole shooting match.

How did SPECTRE come your way?

HvH: It was pretty much through Sam. Although he and Roger have a great relationship, and worked together on Skyfall, Roger was not able to do the cinematography on the next Bond film. Clearly I was on Sam’s radar.

From my side, I had recently finished Interstellar with Chris Nolan, and I wanted to focus for a while on smaller films. You dedicate yourself 100% to a project – you live it, breath it, eat it – and then need to clear your head. It has to leave your system at the end, so you can accept new projects and ideas for those new projects. But when Sam Mendes calls offering you a 007 James Bond movie, it’s a no brainer. It was very exciting, awe-inspiring and frightening all at the same time. I have always loved Sam’s work. He has such a nice eye for detail, and incorporates great cinematography into his films. But a Bond production is spread all over the world, and you have to take part in an inexorable machinery, where the movie has a release date as soon as you start, and must find your visual language within that.

Tell us about your initial conversations with Sam Mendes about the approach to shooting SPECTRE?

HvH: We met in NY and clicked immediately. I had never met Sam before, but from the start we had an intuitive relationship. We are very close on a taste level, have a common understand of how images work, and it was very easy for us to communicate. Sam was interested in my work – I think he enjoyed Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy and Her – and there must be a sensitivity in these and my older movies that he wanted for SPECTRE. We talked early-on about this next installment of Bond regaining a kind of romanticism, to be more warm-blooded and less formal, whilst still being cool. It has lots of action, but some very enjoyable humorous moments too. There’s a new intimacy with James Bond himself who, during his missions is extremely driven and focused, like a hunter.

Did you look at other Bond films?

HvH: Yes, of course. But as much as you are a fanboy, and can be inspired by them, you owe it to yourself to make your own version – the one that Sam and I signed off on – and to move the franchise along. Obviously there’s an expectation – a Bond move has to have certain ingredients – and within those rules you have to find your own ideas. SPECTRE links more to the older-style Bonds, rather than the more recent ones, but has more of a modern, 21st century rule set.

What research did you do and what creative references did you consider?

HvH: For me, stills are always a big help to cross-reference with the director. They contain a mood and a poetry that are concrete, fixed reference points to discuss. I always gather lots of stills during pre-production and testing, put them on a wall, and keep adding and taking away as I refine the look and find my visual language for a movie.

For SPECTRE I started looking at fashion photography – as it has a freer, non-formal style to it – and good, high-end fashion photography has this quality. I also especially liked a number of images made by the US photographer Philip-Lorca diCorcia. He has a nostalgic approach to lighting and his images are stylish, timeless and atmospheric. His pictures inspire spectators with an awareness of the psychology and emotion in a real-life situation. They are glamorous and melancholic. Whilst SPECTRE looks far from a Philip-Lorca diCorcia photo, I felt it was a good thing to have these in the back of our heads when we were shooting. Bond is a journey, through geography, through personal moods and through atmospheres, and we were always aware to create a very particular sensibility to the light in these different situations.

Did you debate digital versus film for SPECTRE?

HvH: We had a lot of discussions about the origination format from the start. We tested digital, Anamorphic 35mm film, and even IMAX. Obviously Skyfall was shot on the ARRI Alexa, but I love film. It has exactly the kind of romantic quality, texture and aura that I wanted to infuse back into Bond. Sam was very enthusiastic and welcomed my suggestion with open arms. The producers, Barbara and Michael, after I presented them with a series of tests, were enthusiastic too. So we elected to shoot film. As filmmakers they recognised the qualities that film can bring and that digital sometimes lacks. Digital lacks the depth and its sharp, gridded and harsh appearance often gets mistaken for resolution. I did my best to make this film as lush and romantic as I could, and film was best choice.

"I had never met Sam before, but from the start we had an intuitive relationship. We are very close on a taste level, have a common understand of how images work."

- Hoyte Van Hoytema FSF NSC

Tell us about your choice of lenses?

HvH: Glass is such a personal thing, from movie to movie, with the different textures and how you want to work with the fall-off and the overall look. On Interstellar Panavision helped me with C-series Anamorphic glass that I really liked. They are always willing to work with you, and have extremely good engineers, creative, insightful, smart people with you as you move on creatively to new projects. So with their help, particularly Dan Sasaki, their mastermind of optical engineering, I repurposed those lenses for SPECTRE. They swapped various elements around and perfected the glass to what I wanted. They even custom-built from scratch a new, 65mm T2.0 Anamorphic lens, based on C-series architecture – a focal length Panavision has never had before – and that became one of our primary workhorses. I felt the traditional 75mm lacked the intimacy I wanted on close-up work, whereas the 65mm is more intimate, and it renders beautifully. That said, it’s a focus puller’s nightmare and Julian Bucknall our A-camera assistant nicknamed it “The Beast.” We also gave names our other bespoked workhorse lenses – the 50mm, we called “The Bullet”, and the 40mm we called “The Chosen One”.

And how about your cameras and filmstocks?

HvH: Our workhorse camera was the Panavision Millennium XL2, as it converts easily from studio mode to handheld or Steadicam mode. I selected Kodak 500T and 250D Vision 3 film, as I like the texture and the dimensionality of the grain of these stocks. In Mexico we used 50D as it was so bright and sunny on the exterior day scenes. On a practical level, I did not want to stop-down the lenses. I love to shoot with low levels of light, as it’s much more interesting for the actors to enter and work in space where there’s an atmosphere and there are fewer lamps on the floor. I don’t think high or harsh light levels are conducive for the actors’ performances.

What can you tell us about your lighting choices?

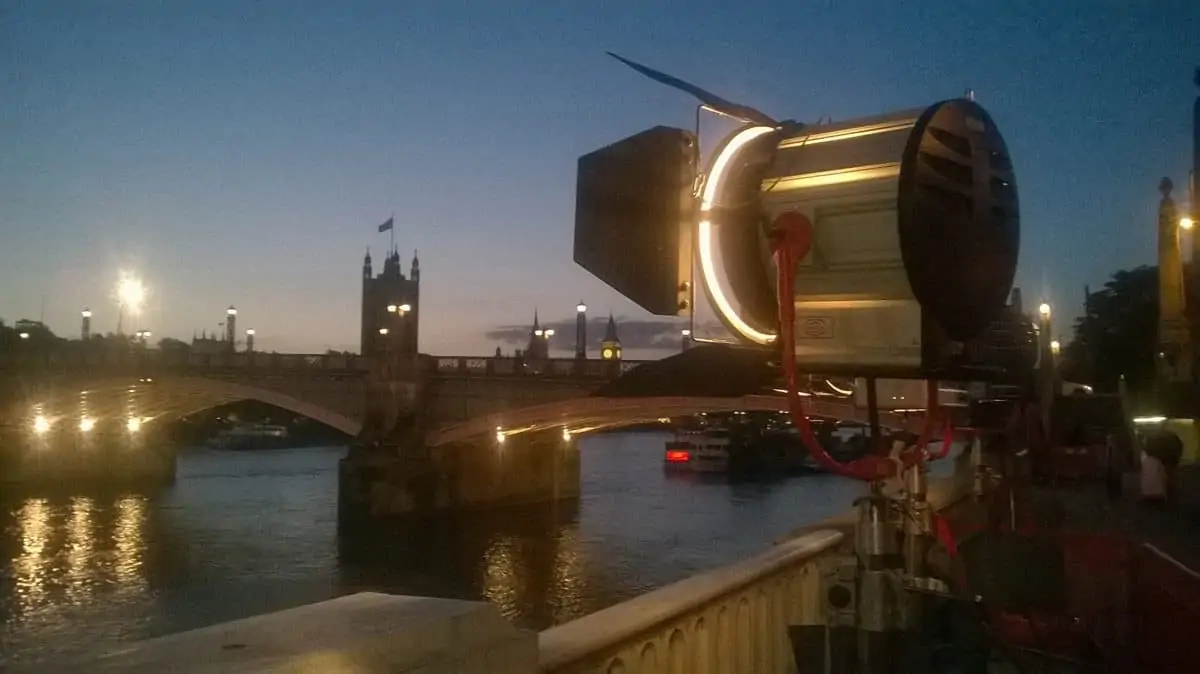

HvH: I have never had such large lighting set-ups before, and I must give a shout-out to my gaffer David Smith, who was my hero and guide in making those very big lighting set-ups work smoothly. For example, for the nightime stunt sequence on The Thames we had 28 generators spread along the river banks, and seven cameras shooting second unit. When we shot on the 007 Stage at Pinewood, we had a 360-degree Translight, and that’s a huge amount of light that needs to be controlled in such a large space. We deployed a lot of LEDs, tube lights and used Tungsten on-stage as much as possible. On big set-ups Dave had the lights under DMX control, which allowed me to dim the lighting as I wanted. And, of course, we had to find intimacy within all of this, and Dave gave me that control for those details too with smaller more intimate lights such as the Creamsource and other homemade LED inventions. Lighting was supplied mostly from Panalux.

Who were your and how did you work together?

HvH: You always want to have willing and creative co-operators on any project, but on a big movie like SPECTRE they are absolutely essential. Normally I operate, but this production was on such a scale that I felt I needed other keen and good eyes behind the camera. I was very dependent on the people around me, and they deserve so much credit for their efforts throughout.

Two heroes for me were Dave my gaffer, and my main unit A-camera operator Lucas Bielan who we imported from the US. Lucas is meticulous, added the sensitivity I wanted, and also added something himself. He helped take the weight off my shoulders. My key grip, Gary Hymns, a Bond veteran, was fantastic. With his good mood and energy he always gave me the feeling that anything was possible. I got along with very well indeed with our first AC/focus puller Julian Bucknall. As I love shooting wide open, Julian faced hardcore challenges, because there is virtually no focal depth on The Beast, The Bullet and The Chosen One. But he dealt with any stress in an ice-cold manner, and always had a sense of humour.

We used Steadicam sparsely, as it was not the main language of this film. But, when we did need those sorts of moves, Julian Morson proved very sensitive. He’s a great camera operator too, so when a second camera was required, it was easy to get Julian in-there and his B-camera material integrated seamlessly with the footage shot by Lucas.

I have also to praise the second unit. Alexander Witt, the second unit director, was very well organised, and worked closely with my friend from Sweden, Jallo Faber, who did beautiful work as second unit DP. Together they paid great attention to the lighting, keeping it tasteful and properly lit.

How did you move the camera?

HvH: Apart from using multiple cameras on action sequences, SPECTRE was mainly a one-camera shoot, especially for dramatic conversation pieces. I like the camera to move in a functional way, with a certain integrity and decency, unmotivated and never for the sake of it. I really dislike it when camera moves are obvious, and I actively censor any ‘jazz’ that happens with the camera. Rather, I prefer a level of restraint, to create tension. If you shout all the time, at some point the audience becomes oblivious to what’s being said. So you take the voice down and people move towards the edge of their seats and listen more. And that’s my approach to the cameras.

We used lateral dolly moves, and we did quite a bit of handheld work motivated by the actors and their emotions. Handheld is very soulful and rewarding when done nicely, and it helped us get closer to the intimate essence in many scenes.

It was great having Lucas. His handheld work is sensitive, with a restrained rhythm and very soft pans, that give the image a romanticism that I really like. It’s like the fashion photography that I referenced – loose, personal and intimate.

Did you have any concerns about shooting on film?

HvH: I had more of a frustration, than a concern. When people keep saying, “Film is dying, film is dying”, it helps to make it die. But film is too beautiful and too good to disregard. With SPECTRE, the Star Wars reboot, Mission Impossible 5 and Quentin Tarantino’s The Hateful Eight all shooting on film, people are reminded that film must be good, and there’s a new positivism towards shooting on celluloid. Thanks also to Chris Nolan and his lobbying efforts, I’d like to think that that it will stick around for a good while yet.

As for SPECTRE, we had two labs to choose from, and I tested them both. They both came back with great results and beautiful prints. In the end I chose to go with i-dailies. As much as I would have loved to have watched film rushes, the turnaround was so fast that scanned dailies went immediately to editorial and the VFX vendors. So we watched HD dailies. Also, as we were doing a DI grade, I didn’t want to put the negative through any possible risk.

How much time do you have for prep and what were the working hours?

HvH: I worked on SPECTRE for a year in total. We shot for 128 days. The lengthy pre-production and prep was very much needed, as there are so many logistics to consider. We scouted all of the locations, knew what we wanted to get out of them, and considered what the weather and the sun would be like at each.

Also, with Bond movies, the interiors are almost always shot on-stage, rather than at the location. Whilst this gives you a huge level of control, it also means you have to be very careful to match the atmosphere and lighting of exteriors with interiors often shot weeks apart. So the lengthy prep was really helpful.

We worked five-day weeks, but that became more like six-day weeks for me towards the end of the production. As the cinematographer you never really rest. I was always looking at rushes, grading trailers, looking at forthcoming lighting plans, scouting a location, or advising the second unit. It’s intense, but I work like a machine on these occasions. Especially on Bond, it’s like an oil tanker moving relentlessly along.

Do you have a favourite scene?

HvH: On a Bond film you tumble from one atmosphere to another. For SPECTRE we shot on locations in London, the Austrian Alps, Mexico City, Morocco and The Vatican in Rome, as well as on the stages at Pinewood. These are each like mini films in themselves, and it was enjoyable to approach them in different ways and create different atmospheres. Although the movie is jam-packed with CGI, our philosophy was to try to do as much as we could in-camera. The most challenging, and ultimately satisfying big scene, was a particularly long shot in Mexico, where we built a huge high scaffold right across the back of a large block of buildings so that we could track a Technocrane to capture a special stunt shot combination. It took two months to build the scaffold and get the rig set, and I doubt if there’s been anything bigger on a movie before. The challenges we had to face up to will be clear to you as soon as you see the movie. Technically, it was a mind-fuck but ultimately very rewarding.

However have a thing for some of the smaller scenes as well. There is a moment in a Moroccan hotel room where it is all about mood, melancholy and intimacy. It became so atmospheric and tender in the film, that even sometimes I forget that it was actually shot in a studio somewhere in a cold, foggy, soggy field near Slough – which is hugely satisfying for a DP.

What can you tell us about working with the VFX team?

HvH: I was closely involved with the previz of VFX shots, such as the one in Mexico, and it’s good to have these well thought-out and to have everyone on the same page when you come to the day of the shoot. Steve Begg the VFX supervisor, another Bond veteran, was always around, making sure we did the right thing for the VFX team. He was clear in his instructions, and it was very helpful in knowing when to shoot bluecreen and what he could rotoscope without needing blue. Peter Talbot did a great job directing the VFX photography.

Were there any happy accidents?

HvH: Yes, with the weather. When we were in Morocco, the shoot was bumped by half a day due to a terrific sandstorm. But the effect was fortunate, as it gave a granularity and cast an atmospheric haze than we could not perhaps have otherwise created or imagined.

Did you do anything special in the DI?

HvH: I did the DI at CO3 with Greg Fisher, who is fantastic. Greg has a very keen and subtle eye for the tender slopes of colour and contrast. He also understands the emotional curves throughout the film. His handling of the original material was always with gentle steps and with huge respect to the original ideas and the negative. We fought hard to go 4K for the most of it to maintain as much as possible of the original texture and sharpness of film.

How was your 007 Bond experience overall?

HvH: It’s very nice to collaborate with an auteur like Sam, as he wanted to make the best-possible movie. It was an absolute privilege to work with Barbara and Michael. They have so much experience, and so much love for the subject and the franchise, yet they were completely open to our input, and very courageous to keep exploring and to keep it exciting. How wonderful that they fully-supported the decision to shoot a cool new film with 35mm on Anamorphic. Sometimes, in exotic locations Sam and I felt we had come home. SPECTRE was a very beautiful, life-altering experience for me, and I’m a very lucky to have been on this adventure. ■

─── Views from the crew ───

Alexander Witt - second unit director/DP

One of the key elements of second unit cinematography is that the images produced are in harmony with the overall visual language of the movie. Following-up similar roles on Casino Royale and Skyfall, second unit director/DP Alexander Witt says that collaboration with Mendes and van Hoytema throughout the whole year he spent on the production, starting in July 2014, was fundamental to the process.

The other key aspect for the second unit is preparation. Which meant Witt working not just with his team, including trusted A-camera operator Clive Jackson, but also with SFX supervisor Chris Corbould on the plane stunt/crash sequence in Austria, and stunt coordinator Gary Powell for the high-speed car chase across Rome.

“We tested extensively for both sequences at Longcross Studios,” says Witt. “We knew that shooting in Rome would be pressurised. We only had one night at each location. Could only start lighting at 10pm at night, due to traffic. And would have six hours before the dawn broke and the light came up. Because of the work we had done prior to the shoot, we had a very good idea about how the sports cars and the cameras would stand up to the rigours of the cobbled streets and stone stairways in Rome, and how to shoot the fast-paced action. Thankfully we were joined by Hoyte’s friend Jallo Faber for this shoot, and I joined in with fourth camera, and it worked out very well." ■

Gary Spratling Associate BSC ACO – second unit camera operator

“It’s very special, exciting and great fun to work on a James Bond movie. It's like a big family, from the moment you walk on set, because of Barbara and Michael and the team of people they like to work with,” says Gary Spratling, second unit camera operator on SPECTRE.

After shooting third camera for Bond’s ferocious dust-up on the Tangier train, Spratling was invited by second unit director/DP Alexander Witt to shoot the river chase and crash scene at the end of the movie, working alongside second unit A-camera operator Clive Jackson.

The speedboat and helicopter sequences were shot on The Thames at night over the course of five consecutive weekends, during the summer of 2015, using ARRI Alexa 65s. The helicopter crash and explosion were filmed separately on 35mm on the 007 Stage at Pinewood, where a full-length Westminster Bridge set had been built.

“Not that you would know that we shot these sequences at different times and locations and with different cameras,” says Spratling. “The set design, lighting set-ups and VFX work were absolutely spot-on and the shots match perfectly in the final movie." ■

Steve Begg – VFX supervisor

The spectacular action sequences in SPECTRE certainly leave the audience shaken as well as stirred. VFX supervisor Steve Begg, whose previous Bond credits include working as a digital effects artist on GoldenEye, and as the visual effects supervisor on both Casino Royale and Skyfall, worked full-time on SPECTRE for over a year, and says the final shots were delivered to post just one week before the world premiere of the movie in the UK on October 26th. It’s understandable. With well over 1,500 VFX shots to manage he says, "SPECTRE was bigger, massively bigger, than previous Bond movies.” Casino Royale contained 850 VFX shots, with Skyfall numbering 1,100.

The main VFX vendors coordinated by Begg on SPECTRE were Cinesite, Double Negative, Industrial Light & Magic’s UK branch, MPC Canada and Peerless. London VFX shop Bluebolt handled various cosmetic works.

Begg worked closely with the production on a daily basis. “I really enjoyed putting my head together with Hoyte, his camera team, as well as Sam, throughout the production. Hoyte and I developed a deep mutual respect, and this level of cooperation – around such things as camera moves, the use of blue or greenscreen, and atmospherics, such as smoke – definitely made things easier for each another and our respective teams.” ■

Clive Jackson GBCT ACO – second unit A-camera operator

Whilst the main job at hand is to capture the action, operating A-camera on second unit, especially on a relentless schedule such as SPECTRE, demands a problems-solving capability.

A regular collaborator of second unit director Alexander Witt, Clive Jackson worked on SPECTRE for five months. “During the plane crash sequence in Austria, because of the schedule and the weather, we found ourselves working on the sequence in separate locations on different sides of the country. The weather was a significant challenge, as the first footage we shot was under cloudy skies, but then the sunshine came out. So we had to plot-out a new shooting schedule for multiple cameras, and ended-up shooting in the mornings and evenings so the lighting would match. Normally you have to wait for the sunshine, but we had the reverse and had to wait for more somber conditions.”

As the production had to shoot the car chase to a very tight timetable in Rome, meticulous testing and prep took place at Longcross Studios. “We really had to be on top of our game. By the time we shot for real on the city streets, and along the banks of the River Tiber, we had a bible of lenses, rigs and hard-mounts, plus pre-rigged pairs of cars, so we were absolutely ready-to-go without any time being wasted,” he adds. ■