Home » Features » Opinion » Across The Pond »

Still buzzing with excitement following this week’s Golden Globes announcements, Mark London Williams’ latest comment piece from LA sees him speak to the filmmaking talent behind The United States vs. Billie Holiday, A Nightmare Wakes, and Bliss.

Normally through the month of February, the business of L.A. is waiting for envelopes to be opened, to see who has won an SAG award, an ASC or DGA trophy, and eventually, of course, an Oscar.

Now the main occupation seems to be waiting to see when an appointment can be made to get inoculated against our particular virus of the moment. Or at least, inoculated against some of its strains. Given that the Johnson & Johnson one-shot vaccine was just approved in the US, some more of those appointments may finally be coming at last.

And some other things, at least, will start to get resolved in the month ahead: ASC nominees will be announced about a week after this column is filed, and then the Oscars a week after that, so we’ll certainly have more on how those races – in this most peculiar of years – are shaping up. And who knows? We may even have had a needle jabbed into our arms by the time the next column goes live.

But for this column, it’s still a matter of masks and home screens (the former, at least, not required when using the latter), with some interesting items popping up on those screens, as well.

Among them, coming at the end of Black History Month in the US, was Hulu’s showing of producer/director Lee Daniels’ new film, The United States vs. Billie Holiday, which reveals that the American government had an obsessive, laser-like focus to get the singer to stop performing her “subversive” song Strange Fruit, which famously took the “subversive” position that lynching was a horrific thing. They came after Holiday by relentlessly pursuing her for drug addictions, and she would die cuffed to a New York hospital bed. But she never stopped singing the song.

A long-gestating passion project for producer/director Daniels, cinematographer Andrew Dunn BSC, recalls the director “first talked about doing this years ago,” with the project being “on and off.” Dunn “never thought we’d do it, (and) the journey to get here was quite long,” but Daniels, he says, “sow(s) seeds of ideas… sometimes these seeds would germinate in a certain way (and) then this magic happens.”

And that magic “wasn’t a laid-out plan,” Dunn says of capturing the essences of certain scenes and moments. Lighting was arranged so actors could “react without looking like we have to dictate, (instead) feeding off performances and actors. Andra (Day, in an astonishing lead role debut as Holiday, for which she just won a Golden Globe) particularly had a relationship with the camera. She just gives this little sidelong glance drawing the audience in. (You) create this space for the actor – to be inside there, to get the audience inside.”

Dunn was used to capturing that magic on the fly, both in previous collaborations with Daniels (The Butler, the pilot for Empire, and Precious), along with the improvisatory rhythms of Robert Altman, for whom he did Gosford Park. He shot this latest project on Kodak film, as well, using a pair of Panaflex cameras with C and E Series anamorphic glass. “Some of these lenses are fifty, sixty years old,” he notes.

But that wasn’t the only retro flourish. They also “used a 16mm clockwork Bolex (which) will have a couple of flash frames when you pull the trigger and jump and start. So when Billie is in some of her worst states of mind (we can) accentuate these immersions. We shot the 16mm mostly colour; high-speed colour, high contrast, (so it) feels like footage from way back.”

And sometimes they would even make the 35mm film “look like the 16mm Bolex stuff,” such as when Holiday is on tour in Europe, visiting cafes and boulevards with her current, and inevitably abusive, husband.

Dunn described the film, and the whole experience, as “one of the ones you wait to come along.” Or, thinking of Holiday’s defiant observation to the Federal Bureau of Narcotics head when trapped in her hospital bed, that he’d already lost because his “grandchildren will be singing Strange Fruit,” perhaps it’s one of the ones that comes back when the time is right. Like Holiday herself. If indeed, Lady Day has ever gone away at all.

Andra Day particularly had a relationship with the camera. She just gives this little sidelong glance drawing the audience in. (You) create this space for the actor – to be inside there, to get the audience inside.

Cinematographer Andrew Dunn BSC

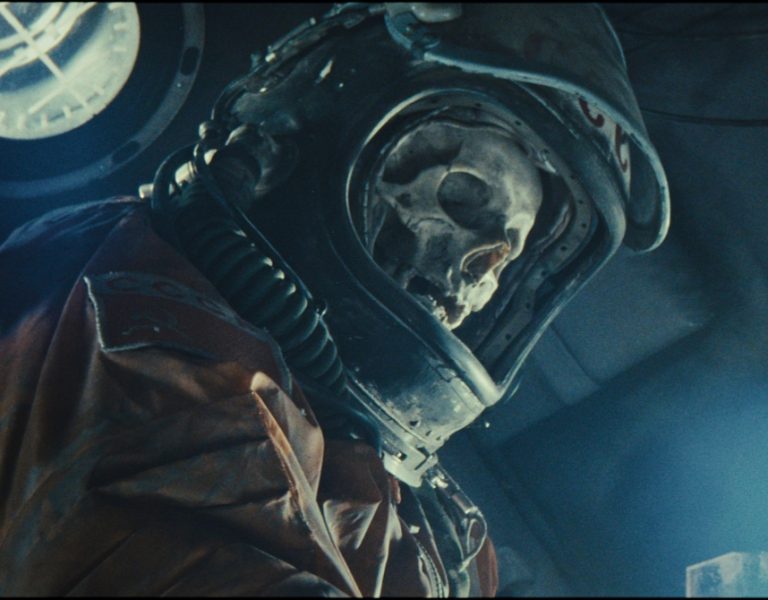

A different kind of heroine – or at least one from a different era – is portrayed on the Shudder channel’s recent Mary Shelley film, A Nightmare Wakes. It’s a feature film debut for writer/director Nora Unkel, who met the DP, Oren Soffer, who lately had been doing lots shorts and commercials, along with the occasional feature, when both were at NYU film school.

In his first film history class there, he “sat next to Nora. We sort of bonded in that class,” later working on both “upperclassmen film shoots,” and a couple projects of their own. Unkel, meanwhile, “started writing this film in senior year, (and spent) a few years slowly developing it, getting it off the ground, trying to find financing.”

Finally, the financing for the small indie production came together, and Soffer found himself lensing for his school pal in upstate New York, which stood in for locations in both Switzerland and England (much as Montreal doubled for ‘40s-era New York for the Billie Holiday film), during that tumultuous, laudanum-fueled period when Shelley came to more or less simultaneously invent both the modern science fiction and horror genres with the writing of Frankenstein.

She also provided the source material for two of the most visually iconic horror films ever made, with both Frankenstein and the-perhaps-even-greater Bride of Frankenstein. Did Soffer feel daunted trying to chronicle the creation of a story with such well known visuals already swirling in the mind’s eyes of its audience?

“It’s something we didn’t intentionally [think] about,” he allows, while also noting that he likes “to subvert expectations. A lot about this project is about subverting expectations about a lot of things. It’s also a piece of historical fiction (with) liberties taken in order to tell this version of the story. Visually, we sort of wanted to create imagery that felt different from what some might call traditionalist.”

Nonetheless, some visual film cues were there, done “a little more subtly – in the scenes that take place in Mary’s mind. We played with a kind of a greenish hue, our homage to classic Frankenstein.”

Lighting was also subtle, being mostly either natural, or occasionally thrown by a candle, or a long sunset. This was captured with an ARRI Alexa with “high-speed Panavision lenses, to create a shallow depth of field look.” Soffer also notes that he operated the film himself, “sort of a typical indie, low-budget production… the first thing to go is the operator!” Though he makes sure to give a shout-out to his “incredible camera assistants.”

The production embraced its limits well though, not only in Soffer’s work, but even making use of their “historical manor home in upstate New York, (which) Doubled as Lord Byron’s manor, and Shelley’s cottage.” This was aided since rooms within in the manor were built at different points in history, so distinct looks could be found on the same location, along with all the exteriors being shot on the same grounds, as well.

All of which allowed them to “build the script around a location,” along with the production itself.

Another tale of two homes, shot on the opposite coast, is the recent Amazon release Bliss, with Owen Wilson looking to leave his current plane of existence for a more “real” one that also comes equipped with Salma Hayek, seemingly as a kind of shaman, or psychopomp for the living, encouraging him to make the leap, and leave family and work behind.

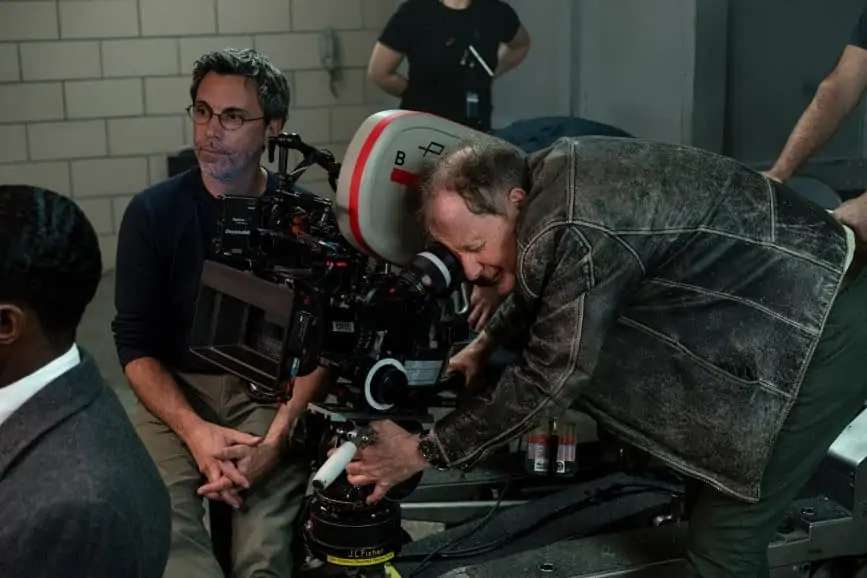

The reality-bending tale represents the second collaboration between cinematographer Markus Förderer and director Mike Cahill, who’d worked together on the previous all-is-not-what-it-seems themed feature, I Origins.

Cahill, Förderer says, “is so visual and visionary. An actor’s director (with) a great sense of giving them their space, (giving) actors their freedom to move, and explore the scene.”

Similar to what Dunn was saying about Daniels in the Billie Holiday project, Förderer tries to get out of the way as much as possible, lighting “for 360 degrees, if possible… so we can just follow the action.”

He was following with a RED Monstro, which he liked for the 8K RAW data it generated, and which, he says, doesn’t “compensate by using artificial sharpening” the way other cameras do. He paired that with Atlas anamorphic lenses, which he notes “hadn’t been used on a bigger project,” and also had “an interesting quality, for ‘Ugly World,’” which is to say the seemingly quotidian world inhabited by the rest of us, that Wilson’s character seeks to escape.

For the moments of, well, bliss that Wilson’s character encounters, under Sayek’s ministrations, there were Angenieux EV Zooms, in order to keep a consistent depth of field, as well. At one point, they considered shooting in 16mm for the “Ugly World” – Bolex aficionados may feel slighted – for a much higher grain contrast with the 8K used for “Bliss World.”

In the end, they went with “using a smaller part of the sensor (to) establish a grainier image,” while the anamorphic lenses “had a certain distortion…this kind of felt right,” for the film’s central question of what, exactly is real, and what is not. Plus, the depth of field had the benefit of “isolating the characters from the environment.”

As for the vivid colours revealed by the 8K, those were further enhanced by working remotely with a colourist, in post, with said colourist in New York, and Förderer communicating via a “colour-calibrated iPad.”

“That worked pretty well,” he says in retrospect. And as we eye a possible emergence from the year that’s been, something “working pretty well” may be as good as it’s gotten.

We’ll see if things start to work even better in the months, and columns, ahead. Meanwhile, see you for more of our not-yet-concluded award season, next time.

@TricksterInk, AcrossthePondBC@gmail.com