SCULPTING 3D

When it comes to collaborating with German countryman Wim Wenders, 2023 was an interesting year for Franz Lustig.

Director Wim Wenders and cinematographer Franz Lustig were responsible for Perfect Days, Japan’s first Oscar entry for Best International Feature by a non-Japanese director, and the eclectic 3D documentary Anselm, about the life and art of German painter and sculptor Anselm Kiefer: two very different films. “Perfect Days was a two-hour movie shot in 17 days which was like a documentary in that we shot rehearsals and said, ‘This is what he’s doing. I’m there. What do you think?’” notes Franz Lustig. “Anselm was like a feature because it took two-and-a-half years, we shot for 37 days and had so much gear.”

Before international acclaim came calling for Wenders and artist Anselm Kiefer, a pledge was made between them three decades ago. “When Anselm was doing an exhibition in the Nationalgalerie in Berlin, he and Wim promised to do this film but nothing happened,” explains Lustig. “In 2019, Anselm calls and meets with Wim. He has this Barjac [studio complex] built over the last 30 years and says to Wim, ‘Go and walk around. We’ll meet for dinner.’ Wim has dinner with him and they said, ‘We have to do this film. It’s now or never.’ The two of them shook hands and the next year we started shooting; that was in 2020. Lucky me, I’m there because I’ve worked for 23 years now with Wim but also, I’m 57 soon and felt ripe to do this kind of project. Before I would have been in too much awe. Now I felt we were on the same level. You could be playful with some things and not be scared.”

From the beginning, the plan was to capture the footage for Anselm in native 3D which was something that Wenders and Lustig had previously done on the short Two or Three Things I Know About Edward Hopper. “We reshot some of Edward Hopper’s paintings from a different angle and that was a mind-blowing experience,” states Lustig. “Before then I was not open to the 3D format because of being too old-school or not progressive enough. Anselm had to be done in real 3D because Wim said that you could only experience the spaces, sculptures and art of Anselm Kiefer that way.”

The production rig provided by Screen Plane had two Sony Venice cameras, two Rialto Extension Systems, two Fujinon Premista 28-100mm zooms and a mirror. “The two lenses had to be synced to the pixel and genlock, otherwise the eye detects every mistake. You have a lot of weight [30 kilos] because of that rig, lenses, and the big zooms. The big zooms [were chosen] because it’s faster than changing prime lenses. You can only move on a dolly or crane or tracks. You could never do handheld.”

The inability to do handheld led to a mini-rig being constructed which weighed a more manageable 11 kilos. “We had to invent a smaller rig to get into these tunnels but to also shoot Anselm at work because that I needed to do that handheld,” remarks Lustig. “I wanted to be with him and have the energy of him. Sebastian Cramer [founder of Screen Plane] worked on it for half a year. Sebastian got six Zeiss Loxia Primes sets of lenses and you have to compare them because they had to match perfectly. The mini-rig was a big step. You lose a bit of time as it takes five to 10 minutes to change lenses that then need to be aligned.”

Cramer was not finished with his inventions for the production. “When they came up with the idea to fly the camera, Sebastian built a drone from industrial cameras that are 4K, RAW, 12 bit and very small so they didn’t need the mirror. As you could change the stereo base during flight, it worked pretty well for wide landscapes. We got these two shots [in -15°C weather]. Superb. Then they fiddled around with the drone to do the other shot in Barjac during the summer.”

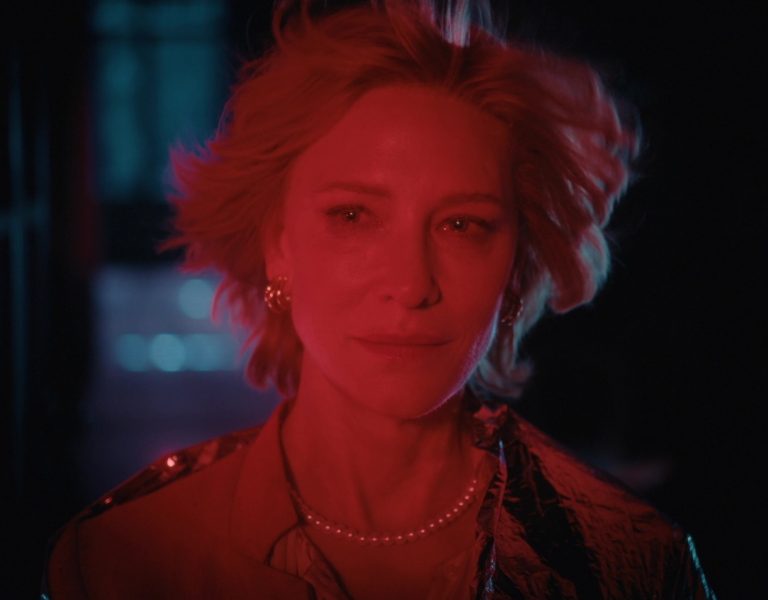

Innovative solutions were utilised for lighting. “You don’t interfere with his art because Anselm has put this submarine tank in the space for a reason and the room built around it is like a warehouse,” states Lustig. “He has around 50 of them there. It has a soft top light. Anselm was lighting the object with his architecture. We came up with this simple idea to hang the silver foil that’s in the first aid kit on the ceiling. We put one lamp on the glass box, bounced that light in there, and that creates this effect, and a couple of Astera Titan Tubes. It was all so subtle. But it was a big difference for him that when Anselm saw it, he said, ‘That’s so ‘Bengalic’, Franz.’”

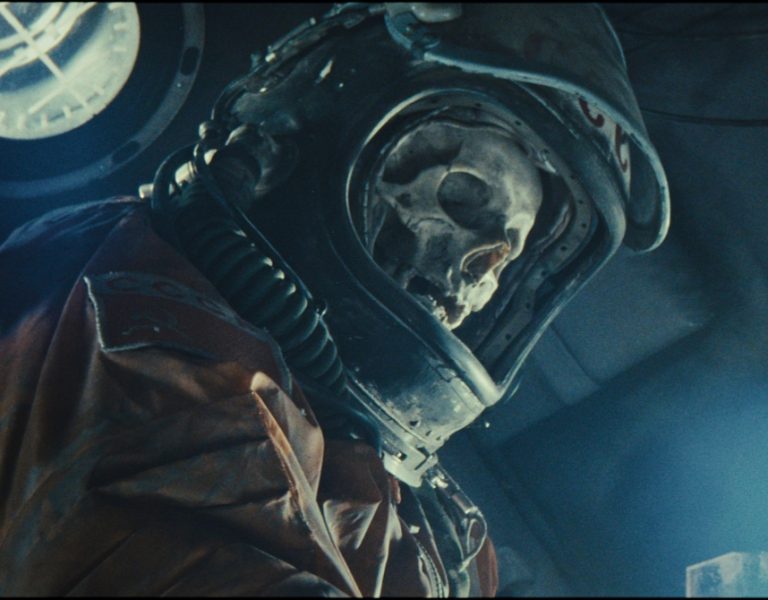

The artwork dictated the 3:2 aspect ratio as well as the colour palette. “Anselm uses brown, gold, blue, a lot of different greys and a muted tonality. I like that and transported it into the other reenactments as far as I could influence it. I did it all in camera.”

A happy blessing was an unexpected snowfall for a reenactment featuring Daniel Kiefer portraying his father. “This is what Anselm painted but that was in the 1970s when there was more snow in the winter in Germany and now it’s too warm for snow,” remarks Lustig. “The summer was amazing in France and for Venice we had blue sky for that graphic shot with shadows on both ends of the gallery at the same angle. It’s the only one time of the year where you have that and we nailed it.”

When the camera enters the industrial, studio-size complex that Anselm Kiefer has constructed in Barjac, what is surprising is the size and scale revelation that occurs when the artist pushes a canvas that dwarfs him, which is in turn made to look like a postage stamp by the massive warehouse environment. “Imagine that in real 3D,” observes Lustig. “Wim said, ‘This is not a documentary. This is an experience. And it’s a really immersive experience only in 3D.’ Your brain has to work much harder to grasp the 3D images because when you watch 2D, a part of your brain switches off. That’s why it’s more tiring watching 3D movies, but they suck you in and you’re there! That’s what we wanted.”