Hart pounding

Eric Steelberg ASC / The Front Runner

Hart pounding

Eric Steelberg ASC / The Front Runner

All images c/o Columbia Pictures

BY: Trevor Hogg

One of the catchiest headlines was published by People Magazine in 1987, which read ‘Hart Stopper’ in reference to Florida model Donna Rice and her alleged extramarital affair that ended the American presidential campaign of Senator Gary Hart.

The circumstances surrounding the political scandal is the subject of The Front Runner directed by Jason Reitman (Thank You for Smoking) and starring Hugh Jackman, Vera Farmiga, J.K. Simmons and Alfred Molina. The Columbia Pictures production is based on the book All the Truth Is Out: The Week Politics Went Tabloid by Matt Bai, who also co-wrote the script with Jay Carson and Reitman; the cinematic adaptation also marks the seventh collaboration between the director and cinematographer Eric Steelberg ASC (Juno) with the duo trying to attempt something different with each subsequent collaboration.

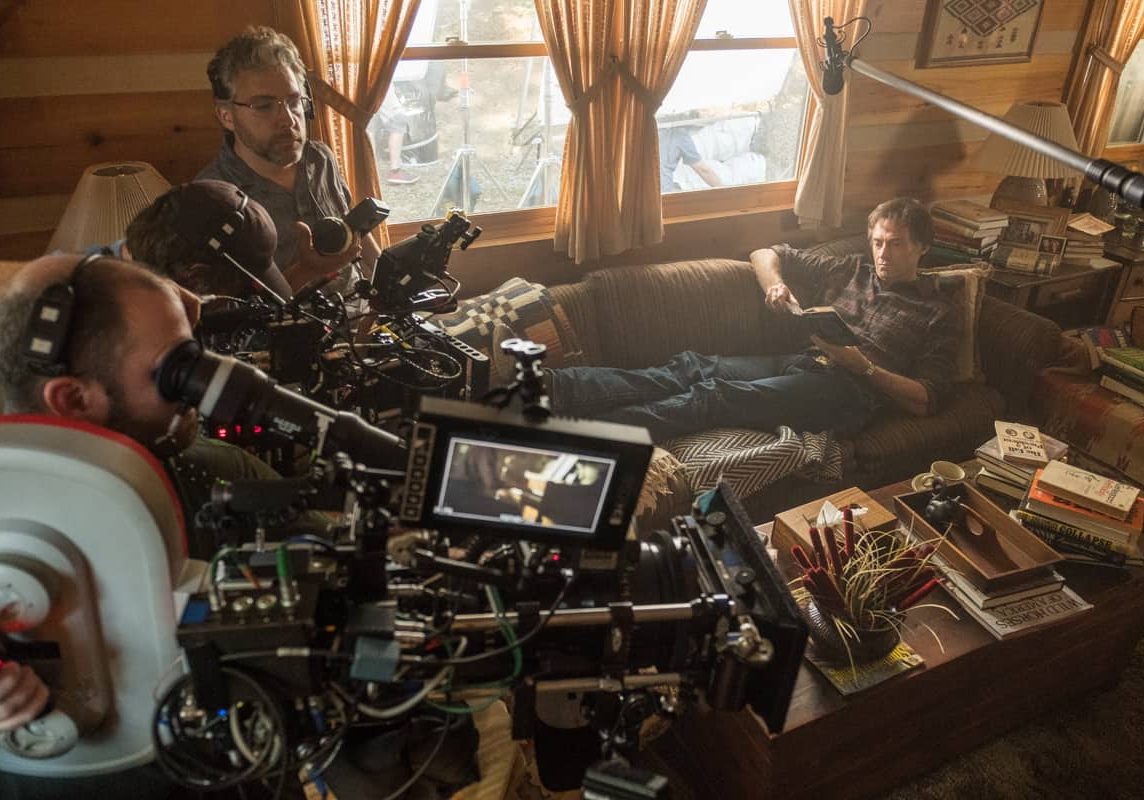

“We’ve gotten more complex with our filmmaking,” notes Steelberg. “There is a lot of moving camera and long single shots in The Front Runner that had to be timed to the dialogue and actions of the actors. There was no such thing as traditional coverage. We decided on the shots that were needed and shot them.” Storyboards were replaced with photographs. “What we’ve done on the last four or five films is, during preproduction, take a still camera, get some stand-ins, go to locations and photograph the scene with them. We try to block it through these pictures to figure out the shots that are going to be needed; then we’ll print those out and put them on a wall or a series of boards. They’re used as a jumping off point and if we come up with something better on the shooting day, then that’s fine.”

Handheld camerawork was sparingly utilized to avoid a documentary aesthetic. “We wanted it to feel more intimate than that but still feel the immediacy and energy,” states Steelberg. “There’s a documentary on the Bill Clinton presidential campaign called The War Room that we watched that was interesting because it felt narrative. Jason liked how it sucked you into the characters but we wanted to have a more theatrical point of view for our movie. Our version of that was these longer single takes where the camera is in round robin way zooming in and out from different groups of people or single actors having conversations within a scene. Everybody is talking over each other and the sound fades in and out as the camera zooms in and out.” Fewer close-ups were shot compared to previous projects which amplifies their dramatic impact. “You’re reading the emotion not only from what their dialogue is but also in their eyes and facial expressions.”

Scene transitions are always kept in mind. “Jason often says onset, ‘I always need to know where I’m going and where I’m coming from,’” reveals Steelberg. “That’s something which is always on the forefront of his mind when we’re figuring out how to shoot a scene which is difficult at times because they get rearranged or cut out.”

Six weeks was spent in preproduction while 43 days of principal photography primarily took place in Atlanta from September to November 2017 with a week spent in Savannah, Georgia which doubled for Washington, D.C.. “Stone Mountain in Atlanta was a stand-in for Red Rocks and Colorado Springs. Visual effects had to replace the background and created a Rocky Mountain skyline behind the actors.”

Initially the plan was to shoot The Front Runner using 16mm film stock. “When we were finishing Tully up in Vancouver, Jason said to me, ‘This is my next movie. This is what I want to do. By the way, I want to shoot on film and explore 16mm.’ I was excited about shooting on 16mm because that’s how I learned how to be a cinematographer. It’s a wonderful format. We shot a bunch of 16mm tests. They worked fantastic. Jason repeatedly said, ‘That’s the look of the movie.’ However, we had such a large cast and so many scenes with lots of people in the background. Unfortunately, the resolution of 16mm, particularly with a higher speed film stock, doesn’t resolve faces in a crowd like you want in a wide shot. It made us nervous, and the producers more so. We shot some tests on 35mm but Jason wanted to make sure that it wasn’t going to be crisp and clean. I experimented with doing some things like forced processing, underexposure, older optics and tweaking the lenses so that we could have some texture and degrade the image slightly to take the edge off.”

"We stripped down the standard Millennium XL2 camera, had a small Prime lens, a 200ft magazine, used video camera batteries to power it that were mounted to the camera, and replaced the eyepiece block with a little monitor. Essentially, we made this camera as physically small as it could be."

- Eric Steelberg ASC

Kodak Vision3 500T 5219 was the principal film stock. “I always knew that we were going to be using the 500 because we needed that for the low light work,” notes Steelberg. “Then the question was for the daylight stuff whether I wanted the 200T or 250D. I liked the way the 200D looked and gave us more resolution when we were using roto around the characters in the wide shot of Colorado. For that I used the 5213. I would also use it for certain times when we were outside. The movie happens in a bunch of different states so I also wanted there to be a variation in the look and pallet of each place.” The DI stuck closely to the dailies with the final grading handled by colourist Natasha Leonnet at EFILM. "Natasha knows the things that Jason and I like and don’t like. That being said we always try to change what we do on every movie. It was more of colour correction pallet than a LUT. I told her that I wanted to keep the texture of the film. Jason and I put colour saturation back into the final colour to warm up the movie a little bit.”

“The Panaflex Millennium XL2 has high definition video taps which was something that Jason expressed wanting to use because we were shooting film again and would help him with the directing of the actors,” explains Steelberg. “They can also be built small for handheld work when needed.” The production was a two-camera shoot that employed zoom lenses: Angénieux 15-40mm, 28-76mm, 45-120mm and Panavision Primo 11:1. “Jason wanted to be able to reframe while we were shooting and being able to zoom in even when we were handheld.” Modern lighting equipment like LEDs were not used in an effort to avoid a contemporary look. “There is a lot of incandescent lighting and even outside we utilized these old FAY lights which were popular back in the day; they could be shot practically and look like lights from news crews. We used snoots, which is like a spotlight attachment that enables you to focus a light on a face without it spilling onto somebody else’s body. A lot of the movies that Jason and I were watching and referencing were shot during the 1970s that mixed hard and natural light. I wanted to try to do the same thing to see if I could evoke a similar type of aesthetic. We used LEDs usually for a TV or light effect or something in a bar in the background.”

For a handheld shot of Gary Hart (Hugh Jackman) exiting a car onto a New York sidewalk filled with reporters into a side entrance of a building a custom Panaflex Millennium XL2 was built. “That was accomplished by a camera operator from the inside of the car handing off the camera to a second camera operator on the outside dressed as one of the people in the crowd who then follows Gary Hart down the sidewalk,” reveals Steelberg. “The backseat of the car was small so there was no way for a camera operator to easily get out and follow him. We stripped down the standard Millennium XL2 camera, had a small Prime lens, a 200ft magazine, used video camera batteries to power it that were mounted to the camera, and replaced the eyepiece block with a little monitor. Essentially, we made this camera as physically small as it could be. The smaller film magazine only allowed us a couple of minutes of runtime. Every take we were changing the mag.”

There was not much discussion about aspect ratio. “Jason prefers 1.85 as he can frame and block for it better than anything wider,” notes Steelberg who was supported by gaffer Dan Riffel, key grip Dave Richardson, A camera operator Matthew Moriarty, B camera operator Cale Finot, dolly grip Sean Devine, and focus puller Sebastian Vega. “The opening of the movie is one continuous two and a half minute choreographed shot that starts inside a news van looking at monitors, comes out, roams around and zooms in on different things happening at a nighttime rally in front of a hotel with 500 extras. The camera is going from person to person and picking up conversations with reporters. We were using the shot to say, ‘Okay. Here is the style of movie.’ There are no opening credits. It hits you hard and fast.” A cabin porch scene with Hart and his campaign staff was significantly cut. “There’s this moment where they know the campaign is over, and Gary Hart gives a long speech. We were struggling how to stage it. Jason and I saw how the actors were hanging out and it looked natural. We did a wide shot of the porch with the light beautifully coming through the trees. I used one HMI light behind the camera. I found another shot from inside the house looking through a doorway because we wanted to have one of Hugh separated from the crowd. Sadly, the scene was used more for a quiet contemplative visual as suppose to having Hugh do his speech.”

“The biggest challenge was keeping the point of view of the film in check,” remarks Steelberg. “There are a lot of different actors who we spend time with.” The reputation of Hugh Jackman is not overstated. “People say he’s the nicest guy in Hollywood. I would agree. Hugh hangs out onset, talks to everybody, and is interested in what everybody is doing and their job. Hugh listens to the conversations that the camera crew is having and if he can help out will do so without even being asked a lot of the time. The best part is that it’s genuine. Even better he is an amazing actor. The camera crew was constantly impressed not just with Hugh but with the other performers as well.” A constant talking point is the cinematic inspiration for The Front Runner.

“Something that comes up a lot is how we were heavily influenced by films from the 1970s. But there was a style of storytelling that we liked from All the President’s Men, The Candidate to the work of Robert Altman (Nashville). We tried to find a lot of things that were done in those movies to evoke a different time period and not to make it feel contemporary. It’s the beginning of tabloid journalism as far as politics goes and we wanted people to know this is a time not too long ago.”