Ellen Kuras ASC Captures Netflix’s Pretend It’s a City

Sep 29, 2021

This article has been shared with permission from Sony. All images courtesy of Netflix.

–

Directed by Martin Scorsese, the ideation of this series began over ten years ago, starring the acerbic Fran Lebowitz, in what is a witty look at New York from her POV. Lebowitz, known for her satire and critical writings, has long been known among New York natives for her frank humor. To Scorsese, he thinks her take on everything is hilarious, and proves it with this modern-day commentary on the city. In 2010, Scorsese created a documentary for HBO with Lebowitz called Public Speaking, which received a Gotham Independent Award nomination. In a recent interview by Steve Pond for The Wrap, Lebowitz explained her reluctance to once again star in a documentary about her. “As soon as we finished, he said, ‘Let’s do another one.’ I said, ‘No, what are you talking about?’ Her reasoning, she said, was simple: ‘Truthfully, if someone told me that there were going to be two documentaries about one person, and that person wasn’t George Washington, I would say, ‘That’s ridiculous.’ And I don’t want to be that ridiculous person.’ She added, “Marty likes the idea of having people filming me while I’m talking…It amuses Marty. He finds it very entertaining.’”

It took a decade to bring Pretend It’s a City to the public, after a pilot called Guest Host, in which famous hosts interview Lebowitz, didn’t get picked up. Netflix ultimately took a bet on Scorsese’s pitch — a combination of Public Speaking and Guest Host with new and archival material — and greenlit the show.

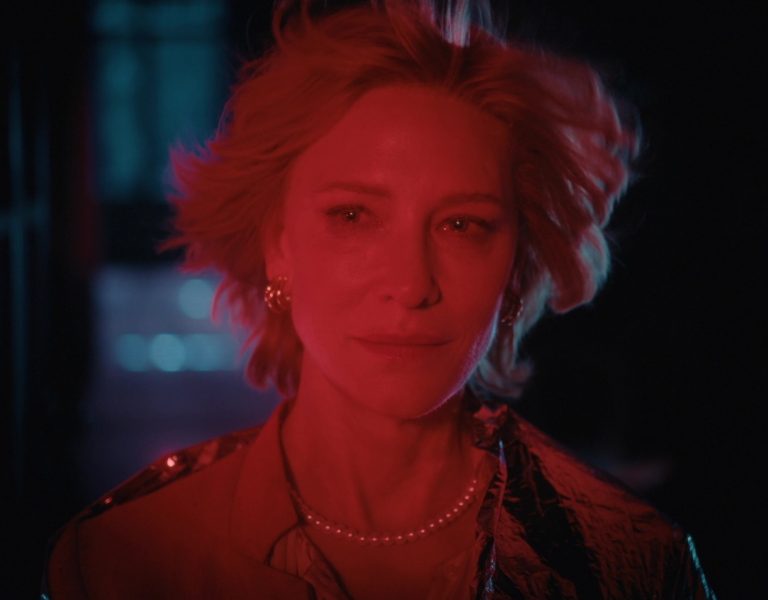

When cinematographer Ellen Kuras, ASC, who has straddled the worlds of documentaries and feature films, including David Byrne’s American Utopia, Jane, Wormwood, Blow, and Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, was asked to come on board, there was no question she wouldn’t do it. Working with Scorsese, “I’ve become part of the family,” she said. Kuras began working with Scorsese over 20 years ago.

Assistant camera operator Rick Gioia started working with Kuras in the late 80s and had done a lot of documentary work with her, but they had never done an entire documentary together. After working for several years with National Geographic, “I learned about getting small and being stealthy and unobtrusive and Ellen comes from that same background,” he said. “Dealing with Fran, my goal was not to overwhelm her with all the tech, and keep her as organic as she can be. Understanding that, I felt like the Sony VENICE allowed us to do just that.”

The show contains interviews conducted by Scorsese with Lebowitz at the National Arts Club, which is a historical club that was founded for theatre people. These conversations took place downstairs in the bar, as a casual roundtable discussion. “I definitely had to light those interviews,” said Kuras. “It was very dark in there. I left the practicals in the shot, but also added a practical, which we thought might be in the shot. The only daylight we had was coming in from the windows, so we had to design the lighting appropriately,” she explained. “I am a big fan of the soft lights, I love these lights, they always feel like tungsten lights to me. LED lights have a specularity that I’ve never liked, whereas tungsten is much more round.” She also had to deal with Lebowitz’s glasses, which was really difficult, “because Fran had aged since the last time I had worked with her on ‘Public Speaking,’ and I knew I had to do much more wrap.” With the first set of interviews, “I had a light bulb, which I put just out of frame on a short arm, low, between Ted and Marty. But when we were doing the DI, every time I saw it, it was driving me crazy. So in the second round of interviews, I took that out and lowered the key line.” Gioia added, “every cinematographer has to deal with that, because of anti-flare, and her glasses were pretty thick.” Kuras said that for her, “I wanted the set to feel like a painting, like a tableau. To achieve that, you have to move the lights around, while using three cameras, and seeing out the window.”

Gioia added, “and Fran’s active physically when she’s speaking, which we also have to take into account. But it was great to see Marty just sit back and listen; his input was the laugh track. You can’t not laugh. So many times we had to bite our tongue and do our job and laugh internally.”

The material shot on the streets was very much docu-style fashion. “We did setups, but she was free to interact with the city however she wanted,” Gioia explained. “We were just there to film it. It was loosely scripted with the context – for instance, the writers’ walk near Grand Central Station – but we didn’t know what she would touch on.”

Even though Kuras hadn’t shot with Venice before, Gioia’s input helped her decide. “One thing I really love about the Venice is the cinematic feeling,” she said. “It reminded me of the look we used to get with the old Kodak 5293, rated at 200 ISO, that had a certain quality and roundness to the blacks. The blacks were softer and I loved the way that it resolved the highlights. I felt like Venice was the closest to that look.”

For the interviews, Kuras chose the Fujinon zooms, starting out with 19-90s. For the second round of interviews, she chose the Angenieux 24-290, which, Gioia noted, “was designed for film, it was never designed for digital. But with VENICE, you can shoot in 4K and the fall off is very pleasing. It doesn’t have a clinical sharp edge. I like the way they work together.”

The street scenes called for a Steadicam, “but when I talked to Marty about it, he wanted to feel really present when he was walking with Fran.” Luckily, the VENICE Rialto had just been developed, “so we were able to get a beta Rialto. We played the card, ‘but this is for Marty!’” laughed Kuras. “The Rialto is so fantastic: it was so intimate and I was able to get really close to Fran and do all kinds of actions, I could tilt up without using a gimbal, and not be encumbered by it.” Gioia agreed, adding, “Ellen is one of the best handheld operators out there and she was able to keep a frame and move the camera, so it wasn’t too hard of a sell to Marty.”

What Kuras loved the most about the Rialto harkens back to the days of shooting film. “When I was using the Rialto and Rick was carrying the pack, for me, it was a way to get my AC closer to the lens again. Now, everyone is 20 feet away with their heads buried in the monitor. I want that old relationship, where your AC is right there, so you could whisper to them. Oftentimes, we were inseparable, and I was focusing by eye and I would ask ‘Rick, how far am I?’”

For Gioia, he believes that is the real loss, in the transformation from film to digital. “A lot of ACs embrace the monitors, but I always kept mine right next to the camera, so I am still in the game. I love being there. That’s where all the magic is. It makes it more human.” It also made Lebowitz more comfortable, Kuras explained. “Because it was just me walking with a lens, you don’t notice the sensor. At a certain point, we gave it to Fran to carry, so we could see her feet, when she was looking down. It was the only time that she was not talking, because she was concentrating on operating. That was the only thing that silenced Fran,” she joked.

The scene where Lebowitz takes a cab was also shot with the Rialto. “Ellen was jammed all the way up in the driver’s seat, while Fran was in the back, and we got some fantastic shots,” said Gioia. “We stashed the body at her feet, and that gave us great flexibility in terms of space.” Kuras said, “I never would have been able to do that, to get a different camera in that position, without the Rialto.”

Another key set for the show was the miniature cyclorama of the city of New York and the boroughs, housed in the Queen’s Museum. It was built for the 1963-64 World’s Fair, and as New York grew, they kept updating it. “I had never seen it before, but seeing it in person was pretty mind-boggling,” Kuras said. “I was able to light it, but it was a really difficult set to light, because I couldn’t light from the center, and I couldn’t change the lights surrounding it, I could only turn them off.” The crew were only allowed in the viewing alleyway, around the whole miniature. “We ended up blocking lights, separating them by flags,” she explained. We left the back lights in and blocked the front lights as much as possible. I had a light with a Chimera, which was really tricky.” They managed to get a crane in, because Kuras wanted to have an overhead shot of the view as you approach La Guardia airport. “I had just been on a plane going into La Guardia, and I took some pictures. We managed to get a Technocrane in there, and Marty really wanted a shot where we skim over the city and find Fran standing there in the Hudson River. It was tricky to maneuver the shot. I couldn’t be there for the prep, so I had to pre-visit in the tech scout. That was when we were shooting in Manhattan, and I was driving with Fran in the taxi to shoot that sequence.” Kuras said. The crew had to wear booties while they were shooting, as the cyclorama was really delicate, “and it was hard to walk over the bridges.” Lebowitz was told not to hit the bridges with her feet, “but she kicked over the Manhattan Bridge, although that never made it in the show,” Gioia said. “I was horrified when it happened, and so was Fran,” added Kuras.

Shooting in the subway, for a scene about an art installation, the two of them debated whether they had permission to shoot or not. “Did we steal that?” Kuras questioned. Gioia replied, “In New York, we almost always steal the subway.” But, Kuras remembered, “I think we did have permission at that station, although they didn’t clear people out. We had to be there at a prescribed time, and we had a ridiculous small amount of time to shoot…like fifteen minutes. I could see Fran rolling her eyes.”

Another scene took place in the iconic New York Public Library, “which, contrary to the subway, we had a lot of access, because, of course, it was Fran and Marty,” said Kuras. “When we were setting up, they both walked up to the library at the same time, and looked in the windows at the same time. Neither of them is tall, so I’m sure they were on their tippy toes to look through the window. I couldn’t really light that area, it was difficult, because the whole library has gone through a transformation. We put two dolly tracks in there, and I let the cameras go back and forth in a rock-and-roll fashion, and let the cameras catch them. Fran and Marty were really enjoying that, just walking through the stacks, not knowing what camera was on them.”

Gioia added, “The fact that VENICE can go to 2500 EI, helped Ellen in these difficult lighting situations, allowing her to use more natural lighting. I think that is a great feature of the camera, and at 2500 it gives it a little more granularity, and it’s great for the blacks.”

“I chose the Venice, not only for the Rialto, but the feeling and look of it,” said Kuras. “What was really important was the dynamic range, and that was vast. I do like to blow out the highlights and have some details in the shadows, so I feel like I have a lot of control over the image, much like I did shooting film.”

For Gioia, the ND filters “are a brilliant feature. Any time we went outside we used them. You don’t have to worry about the IR factor, because they are balanced for the sensor. Even when we got into the heavy ND for a bright exterior, it didn’t change the color balance.”

As the two of them discussed a scene shot in the Argosy Book Store, one of the last remaining bookstores in New York, Kuras reflected on how the story she wanted to tell is reflected by the bookstore, which is still going strong. “New York has changed all around the Argosy; it is dwarfed by skyscrapers. We went up in a manually operated elevator to the 3rd floor. Windows looked out across to another skyscraper and a floor filled with computers and young traders. I thought, ‘look at the irony here.’” Gioia noted that, “it’s two different centuries across from each other.”

Kuras explored it further. “That’s one of the points that ‘Pretend It’s a City’ makes: the message in the subtext is about the things that we have lost, in the so-called industrialization of our minds, when we get further and further away from things that are tangible and tactile.”

To which Gioia added, “And the great thing about Fran is she doesn’t care about being politically correct. She is unabashedly literate. ‘I know this because I read,’ and that informs her sense of New York. A different person might try to underplay that, but she doesn’t care. She’s like the anti-pop celebrity.”

–

This article has been shared with permission from Sony. All images courtesy of Netflix.