Home » Features » Interviews » Visionary »

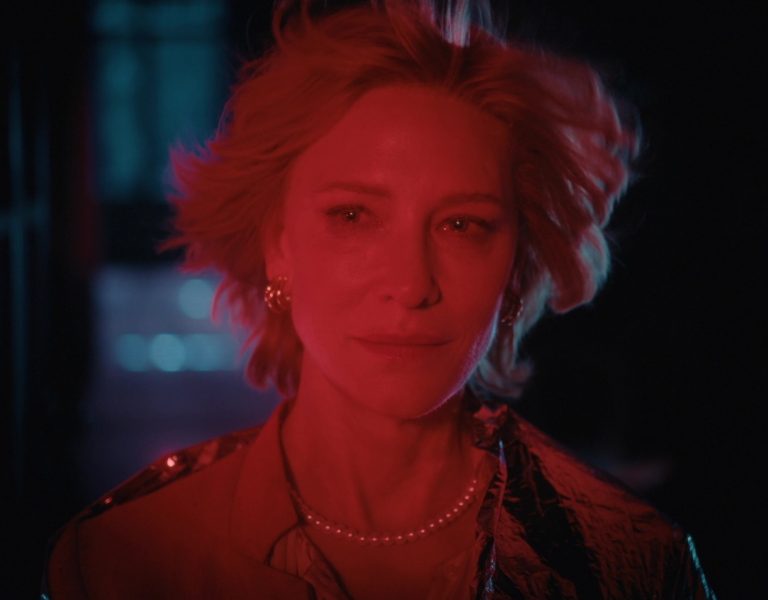

SUPREME STORYTELLER

While at Brown University, studying semiotics and social anthropology in the late 1970s, Ellen Kuras ASC, took a photography class at Rhode Island School of Design. It was a move that changed the course of her life, as she found herself intuitively drawn to stories told through visual mediums and was fascinated by the idea of propaganda and how meaning is created in film and photography.

After moving to New York City in 1982, Kuras began working as an assistant on documentaries and as an electrician on dramatic films. During nights, she completed the coursework for a master’s degree at New York University, and decided to do her thesis project as a continuation of the work she’d begun in Rhode Island, documenting her Southeast Asian refugee neighbours and exploring the line between documentary and fiction. Seeking a Laotian language teacher, she hired Thavisouk Phrasavath, who would eventually become her friend, subject and collaborator on The Betrayal – Nerakhoon (2008), the documentary that would garner Kuras’ first Oscar nomination and Primetime Emmy win.

The Betrayal was the reason Kuras became a cinematographer. She first began the film as the director-filmmaker and had hired a cinematographer to shoot. When the first days of dailies came back, she saw that they were beautiful images, but realised that they didn’t really say very much, they didn’t tell the story. So, she picked up the camera to explore what it is to create meaning with the camera, and in doing so, that was the beginning of a lifelong inquiry into visual metaphor.

Though Kuras started The Betrayal back in 1985, she didn’t finish the film right away, citing creative reasons: “I didn’t want to edit the film in a traditional documentary way,” says Kuras. “Most documentary editors at the time would first edit the interviews and then stick in the images to illustrate the words. I needed the images to be seen as visual metaphors and having as much power as the words to tell the story.”

She and Phrasavath turned to editing the film themselves to try to remain true to the visual approach. Another roadblock in finishing the film was that she couldn’t access the archival material she knew she wanted to complete the story – not only was the material highly classified by the US government, but Laos was also a communist country closed off to the world. Needing to show memory and first-person narrative, Kuras turned to creating her own archival footage in the spirit of the truth. Financing the film through grants and her own pocket, she ended up working on the project whenever she had free time. After nearly two decades of doing that in between shooting films, Kuras saw how the United States and Britain were entering Afghanistan and Iraq, and she felt that the story of The Betrayal -about the devastation left behind in Laos after the Vietnam war – needed to be told. This was 2006, when Kuras was at the peak of her career.

“I’d had half a dozen scripts on my desk asking me to shoot in 2006 and I was about to begin prep on Recount (2008),” she says. “My film felt like an incomplete sentence, so I knew I had to go back to it with resolve.”

The Betrayal was accepted at Sundance Film Festival, where it was nominated for best documentary and went on to be nominated for a Film Independent Spirit Award, an Academy Award and won a Primetime Emmy.

During those two decades, Kuras was constantly working on films – first, as a cinematographer on big studio films like Blow (2001) and Analyze That (2002), and for beloved independent films too, like Swoon (1992) and Angela (1995), both of which won her Sundance Jury awards, Summer of Sam (1999) and Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (2004). But Kuras had always wanted to direct, and considered herself a “filmmaker,” not wanting to be limited as either “director” or “cinematographer.” She wanted to be both.

“My first avenue of being able to enter into filmmaking was through documentary,” says Kuras, who counts Costa-Gavras, Gillo Pontecorvo and Stanley Kubrick among her early filmmaker heroes. “Films like Z (1969) and Missing (1982), I just loved the way Costa-Gavras dealt with suspense and drama, often using real-life situations in such a way that we understood the politics of it. Another really influential film for me was Pontecorvo’s The Battle of Algiers (1966). I was blown away by his creation of a film that looked like a documentary but was actually a drama. Tom Laughlin’s Billy Jack (1971) opened my eyes to changing points of view. It was the first time I saw a ‘Cowboys and Indians’ film that was from the point of view of the Native Americans, and it really took me aback. And of course, 2001 A Space Odyssey, opened up a whole other way of thinking about human existence and narrative.”

Kuras feels that those films stayed in her psyche even as she was headed toward a different type of career path in social anthropology, and that they informed her even more when she began making her own movies. She was also hugely influenced by her year studying in France, where she attended École des Études du Cinema in Paris. There, in a fully French-speaking program, she studied the basis for meaning and perception as it related to the psychoanalysis and psychology.

“I came to the camera part of filmmaking with a director’s eye,” she explains, referencing her many years shooting feature films in NYC and around the world, “and was often asked by many when I would start to direct, but I felt like I couldn’t actually dive into directing until I finished The Betrayal.”

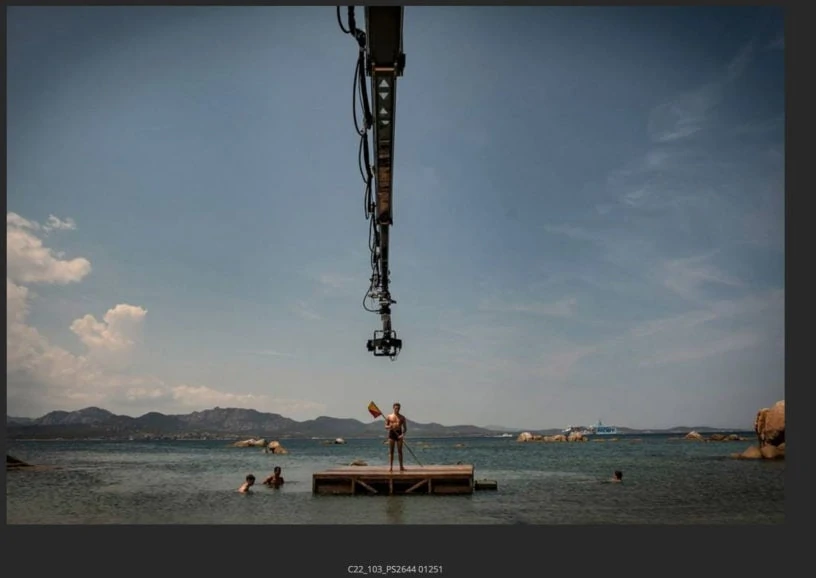

After The Betrayal was released in 2008, Kuras felt freer to concentrate on directing because she had a clean slate and also more confidence because of the success of The Betrayal. She began working on commercials at Park Pictures as a director-DP and continued to shoot for features like the sweet Away We Go (2009) and the luscious A Little Chaos (2014); Netflix’s limited series docudrama Wormwood (2017) and more recently, Fran Lebowitz’s Pretend It’s a City (2021). And in 2016, she also began directing TV episodes and has cut her teeth in the new golden age of television on shows like Ozark (2017), Legion (2018), Catch-22 (2019) and The Umbrella Academy (2019).

“Moving into episodic TV to direct is a big transition for most,” says Kuras. “But I have to say that for me, I’d been asked for a long time when I was going to start to direct. And I think that’s because the way I always approached cinematography was as a director – thinking about how where I put the camera can help create meaning for a scene or using lighting to create emotion for the story. I was asking questions and helping directors to design the looks of their films just like a director would do and I wasn’t being presumptive or arrogant, it was just a way of collaborating for me.”

Kuras freely admits that she knew she always wanted to be able to control the overall picture in filmmaking. It was the nature of needing work that steered her into cinematography, which she also admits to loving, in addition to her blossoming career as a director.

“I love the way the camera can speak,” she says. “I love the way the camera can create meaning. It was a natural course for me to shoot for all those years, but I realised that I really did want to be able to create stories that go beyond the contribution of the cinematography.

When the pandemic hit, it stalled the final stages of financing and prepping for her first narrative feature film, LEE, an international biopic with Kate Winslet as photographer Lee Miller, a fashion model-turned-acclaimed war correspondent for Vogue magazine during World War II. But she was able to continue her work as a DP on Martin Scorsese’s documentary about David Johansen, front man for the New York Dolls, and is currently directing the second episode on Amazon Originals’ thriller, The Terminal List, with creator and director Antoine Fuqua and Chris Pratt.

“It’s harder for [small films] to do adhere to both internal protocol and state protocol,” says Kuras, shifting her focus to the challenges she currently feels in the industry. “Even on a big studio show, I’m experiencing those difficulties and added costs: all the key players – myself, the producers, the assistant director, the cinematographer – we all have to self-drive while doing a scout. It’s enormously tiring and cuts off the conversation that we would all be having in a van together. We’re really feeling that gap in communication, that creative synthesis that happens when people come together and start forming ideas. Everybody’s just trying to get back to a semblance of normalcy, but you can’t look at what’s happening from a place of isolation.”

While that is the impact in an immediate sense on the creative process, Kuras feels that the bigger picture looks brighter as more people get vaccinated. She has heard from sales agents trying to put together deals, that movies are coming back, though she doesn’t believe we’ll ever see the industry like it was pre-Writers’ Strike in 2008. But Kuras, never daunted by change, has adapted many times over to a morphing industry and, more to the point, to her own sense of transition and evolution. It’s thrilling to see what this next stage of her career will bring to us all.