IDENTITY IN A NEW LIGHT

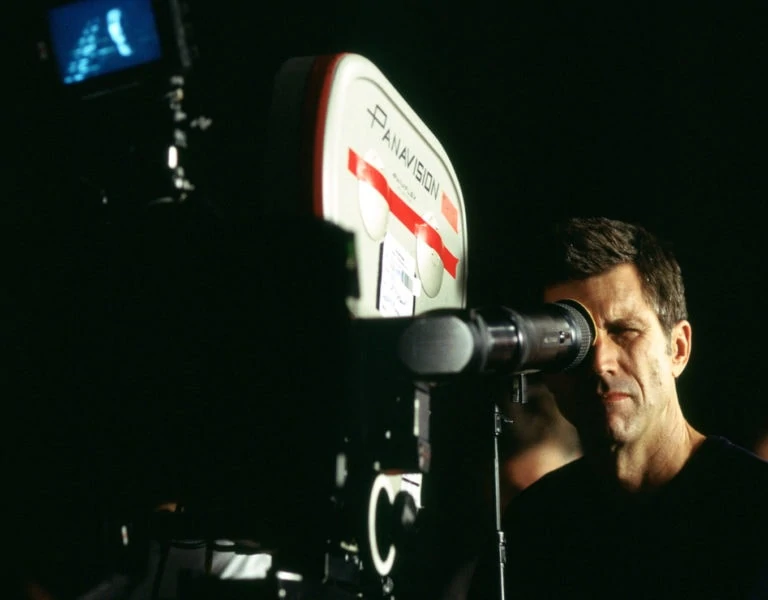

Cinematographer Edu Grau ASC AEC felt honoured to be asked to shoot Rebecca Hall’s directorial debut Passing. He tells us about enjoying a new type of creative freedom and why it was important to tell a story of race and identity in 1920s America that has rarely been portrayed in film.

Based on Nella Larsen’s 1929 novel, Passing explores the practice of racial passing in 1920s Harlem. Rebecca Hall’s powerful adaptation homes in on the relationship between mixed race childhood friends Irene (Tessa Thompson) and Clare (Ruth Negga) after they are reunited as adults. The film examines the carefully constructed realities of Irene who identifies as African American and Clare who “passes” as white, along with their envy for each other.

“I read the script multiple times – it was like a fascinating puzzle,” says cinematographer Eduard Grau ASC AEC. “I’m attracted to films where the answers are not immediately obvious, and this movie grows in your mind, forcing you to think deeper.”

As a DP, there aren’t many opportunities to shoot movies like this.

Edu Grau ASC AEC

Before Hall moved behind the camera to make her feature directorial debut Passing, Grau captured her performances in The Awakening (2011) and The Gift (2015). “She always struck me as a person with vision, whether she was acting or directing,” says Grau. “Rebecca is such a clever director with a profound understanding of performances and visual language, and it was an honour to be asked to shoot Passing.”

From the get-go, Hall wanted Passing to be shot in a 4:3 aspect ratio in black-and-white. Visual concepts were then developed using the novel and its vivid characters as inspiration. “As a DP, there aren’t many opportunities to shoot movies like this,” says Grau. “4:3 black-and-white films often go in the direction of art house and veer a little off the beaten path – they are the kind of films I’m most passionate about.”

Subscribe to our mailing list to continue reading

Hall and Grau agreed the story would be best told in black-and-white not only because it is set in the 1920s but mainly due to the film’s focus on discrimination based on skin colour. “Passing explores what it means to be black or white, but there are also grey zones which the people who are passing sit within,” says Grau. “Not shooting in colour also made it more difficult for the audience to distinguish who is white or black. And the form becomes part of the content which is what any filmmaker strives for.”

The pair also set out to make a film “rooted in classic cinema whilst venturing into more contemporary techniques”. Productions referred to during prep made by contemporary filmmakers included Pawel Pawlikowski’s Ida (2013) – which was also shot in 4:3 black-and-white – alongside Hitchcock classics such as Notorious (1946) and Rebecca (1940) or David Lean’s Brief Encounter (1945).

Black-and-white helped overcome certain lighting challenges and offered a beautiful way to craft images with a focus on luminosity, contrast, and composition. Gaffer Stefan Lan and Grau told the story through illumination by examining direction and softness of light and playing with shadow.

“The characters also play with shadow and light to reveal who they are and how they behave,” adds Grau. “They are pretending or wanting to be someone else, so we played with the concept of light and darkness, beginning and ending the movie with whiteness and introducing more contrast in the middle.”

Lan worked with a small, conventional and predominantly LED lighting package including ARRI S60s and S30s. “Occasionally, we needed HMI or tungsten lighting and we might mix multiple colours of light that looked terrible when shot in colour but great in black-and-white. That was one of the practicalities of adopting that approach,” says Grau.

Multi-dimensional storytelling

Apart from the construction of the hotel room set, Passing was shot on location in New York over 23 days, following a five-week prep period. Finding locations with the correct tone for the era was crucial. These were then refined with the help of production designer Nora Mendis. “We faced limitations but tried to be as accurate to the period as possible. Sometimes limitations make you a better filmmaker as you become more creative and often simplify your approach,” says Grau.

“Shooting black-and-white helped us shoot a period film in New York on a limited budget. Some things disappear into the grey so they’re not as noticeable as they might have been in colour. Black-and-white creates a simpler image and that helped the storytelling as it focuses the audience on the important things.”

Working in 4:3 – Grau’s first time shooting a feature in this aspect ratio – also helped by limiting the audience’s field of vision and allowing him to control what is in the background. The 4:3 aspect ratio gave the filmmakers the ability to box in the characters, reducing their worlds. “They live in their own beehives. It also helped define their personalities. For example, Irene lives with her family and does not wish to expand her life whereas Clare is a wild card trying to escape the constraints of her life,” says Grau. “Therefore, we shot Irene as very static and composed in the frame. In contrast, Clare’s compositions are wilder, more luminous and creative.”

Having already decided to shoot Passing with the ARRI Alexa Mini, partly motivated by the way it handles skin tones, Grau ran extensive tests to find a lens with “texture and personality”. Struggling to find a suitable 4:3 spherical lens, Grau realised anamorphic could offer the solution and opted for the Lomo Anamorphic round-front lenses, supplied along with the camera, by ARRI Rental in New York.

Grau admits selecting anamorphic for a 4:3 aspect ratio film might seem an unconventional choice because only the centre of the image is used, but when he saw the results of the tests on the big screen, it was clear the lenses had a “personality and touch” rarely seen before in 4:3 black-and-white.

“We used slightly more than half of the camera sensor, but the image produced was beautiful,” he says. “We wanted slight imperfection, and a poetic quality in the highlights. Finding those lenses was a miracle – they told a story, the bokeh was stunning, and they offered a texture and painterly quality difficult to find in modern perfect lenses.”

Passing experiments with dimension, at times adopting a flatter more two-dimensional approach to present the world as the characters experience it. Grau also ventured into the tri-dimensional – adding another level of depth to get inside a character’s psyche, a technique deployed successfully in some of the classic films Grau watched for inspiration.

For instance, Grau explored the effects created when combining 1 and 2 diopters with the Lomo lenses and then experimented with shallow depth of field, unusual framing, and handheld shooting for scenes such as the one which sees Irene in a sedated state. “Overall, the movie is elegant and static, but I like the scenes where we break that rule for a good reason and show a third dimension to understand the world the characters inhabit,” he says.

Grau believes contemporary cinema can sometimes be too sharp and defined, not leaving enough to the imagination. “We wanted an image with an ethereal quality and that was a bit more impressionistic. This is getting harder to achieve in contemporary cinematography because everyone aims for crazy resolutions. Often, the sharper the image, the more it is praised,” he says. “We should look at an image in terms of whether we like it rather than assessing it by a number. We were hesitant at first because we were working with a resolution of 1.7K but it was magical on the screen – we let our senses lead us, hoping the audiences will marvel at it.”

Exploring identity

To help tell a story that is fundamentally about identity, Grau incorporated reflections. He chose to play with mirrors because “sometimes you like what you see in a mirror and other times imperfections appear in the reflection”.

Camera movement was reduced and simplified to align with the characters’ movements, especially Irene’s. Grau tried to be as diligent and economic as Irene is with her movements and never used the camera in a way that did not complement what a character was feeling or thinking.

Collaborating with his “exceptionally supportive crew” – which included 1st AC Bayley Sweitzer, camera/Steadicam operator Aaron Brown, and key grip Robert Stile – Grau used repetition in sequences such as those tracking Irene walking through her neighbourhood as the seasons change. “But in general, we wanted to keep everything quite boxed in and reduced,” he says. “Rather than trying to explain what was happening in 1920s New York, we were in Irene’s world, explaining what was happening inside her mind.”

Scenes in the dancehall broke this mould, introducing a rush of energy by adopting a looser, handheld approach. “It was important to capture the vibrancy of that moment in time in Harlem and the importance of music for that generation,” says Grau.

Passing’s pivotal final scene also ventured outside the film’s predominantly static style resulting in a hectic handheld sequence conveying the turmoil experienced by the characters. “The sequence surprises you but it felt like it was aligned with the mood of the character – it had a vibrancy and was enhanced by the disconcerting feeling of handheld,” he adds.

Grau worked with colourists Joe Gawler and Roman Hankewycz at Harbor Post to create a LUT that allowed him to capture images with high contrast that were later fine-tuned in the grade. Hall and Grau were keen to use the LiveGrain real-time texture mapping tool to add 35mm grain to the image. “It adds this texture, roughness and character – making it more believable and rooted in that era. Early on, Rebecca and I said, ‘We don’t want to see this movie without Live Grain’. Ensuring the image was rooted in the ethereal and had a painterly poetic quality became an obsession.”

Aside from the creative opportunities Passing presented Grau with – allowing him to explore the 4:3 aspect ratio, shoot in black-and-white and work with LiveGrain – the production opened his eyes to a part of American history he was unfamiliar with. “I didn’t know about the black bourgeoisie society living in Harlem in the 1920s,” he says. “It’s a socio-economic structure and world we don’t often see portrayed in film and I think it’s important that this part of American culture that has been negated for years is now being highlighted. That’s part of what we do as filmmakers – shine a light on important topics so audiences can understand them.”