Practical Primaries

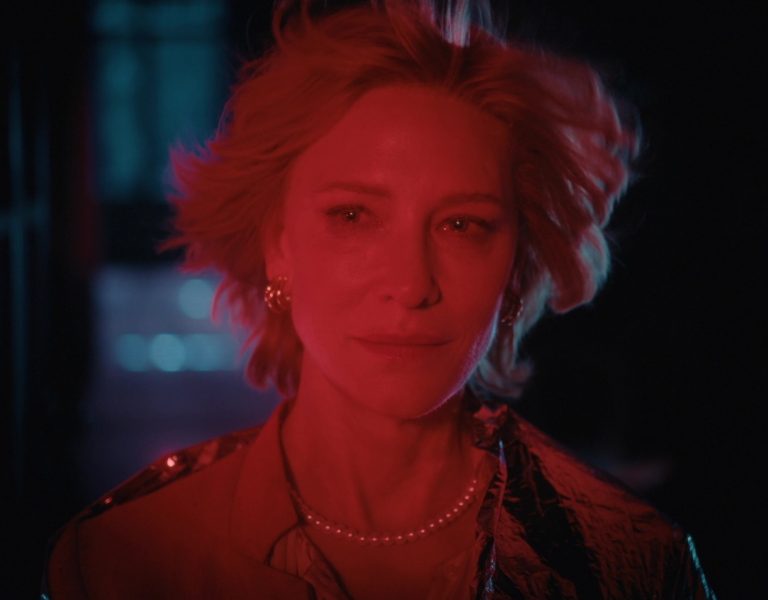

Innovator / Curtis Clark ASC

Practical Primaries

Innovator / Curtis Clark ASC

BY: Carolyn Giardina

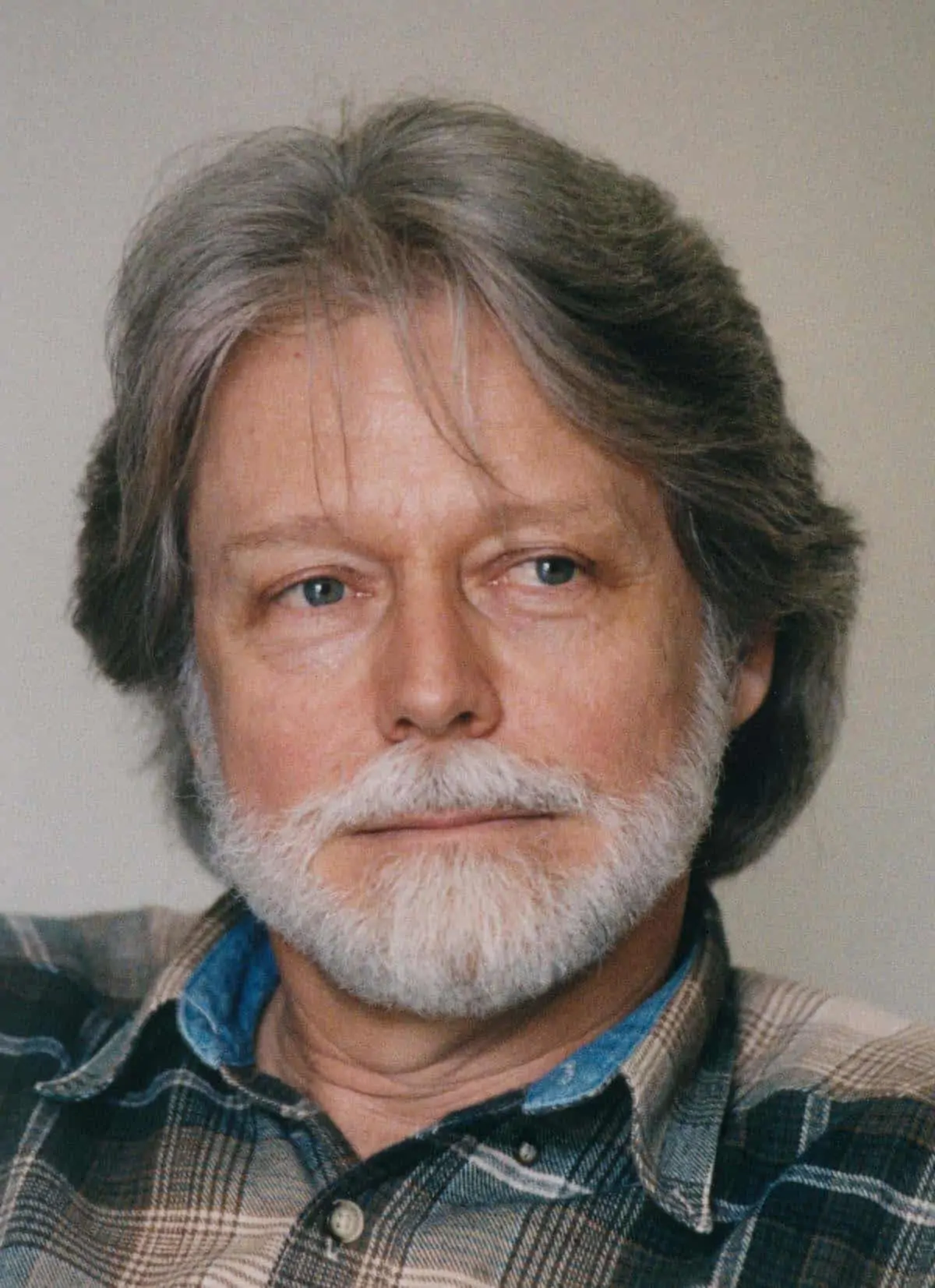

As a cinematographer, Curtis Clark ASC is known for pushing creative boundaries. As the chair of the ASC Technology Committee since 2002, he is also leading the charge to investigate new motion picture technologies and champion workable cinematographic and display solutions.

It’s a huge undertaking, made even more vital as digital technology continues to evolve and advance. The ASC Technology Committee maintains a large and active membership, including vice chairs Richard Edlund ASC and Steven Poster ASC.

Its stated goal is: “to examine and understand emerging motion imaging technologies so that it can advise its membership and the motion picture industry on the convergence of these technologies with traditional motion picture techniques.” Carolyn Giardina caught up with Curtis Clark ASC in LA to discover more.

BC: Tell us about your background and how it inspired you to address technical initiatives.

CC: I started my feature film career with The Draughtsman's Contract (1982), made in England with Peter Greenaway, which was an immensely successful film that had its own technical challenges. I had to shoot numerous scenes at very low light levels using candlelight, and found that depth-of-field was going to be a problem with 35mm. I needed to be able to shoot at T1.3. I had the idea to experiment with Super 16mm, because it has an intrinsically bigger depth-of-field, and find a way to enhance the image quality of the 35mm blow-up reproduction. We kind of pioneered that process. I had a very special relationship with the film lab that helped us take the right steps, and recall getting wonderful support at the lab from Len Brown and Paul Collard. From the selection of the sharpest lenses with optimal exposure, to the way we handled the blow-up, it had to be done very carefully. The objective was that anyone who saw the finished film wouldn’t know it wasn’t 35mm origination, and it worked perfectly.

I loved the fusion of how technology finds solutions to enhance the art form. I continued to do that on almost all the films I’ve photographed, such as Alamo Bay (1985). This led to my awareness of, and being drawn to, technology solutions that best serve the art form of filmmaking, particularly cinematography.

BC: Tell us about the formation of the ASC Technology Committee?

In 2002 I was asked to form the ASC Technology Committee. The ASC realised we were entering into new world that would be filled with uncertainty and disruption during the transition from everything being shot on film and finished on film, using an end-to-end photochemical workflow, to the Digital Intermediate process, initiated by Kodak with its innovative Cineon system. But DI was just the starting point of the emerging digital imaging revolution, which then progressed to digital cinema projection and eventually digital motion picture cameras.

BC: A notable initiative was the development of the ASC Colour Decision List (ASC CDL). What impact have you seen from this, and is there more work ahead?

CC: It’s hard to find a production that doesn’t use the ASC CDL; it has become a de facto standard. Its flexibility is the secret to its success. It can be used within ACES or any colour space reference. It’s a very mature and robust technology. There’s continual suggestion and encouragement to expand it into secondary colours, and that presents a bit of a challenge. Once we start doing that we are in effect starting to develop a colour corrector.

At the moment we have most post-production technology vendors implementing our current RGB primary colour grading; it’s been a universal adoption. If we start to move into supporting secondary colour correction, then it might become a question of how readily they will continue to adopt it, because we are now starting to potentially compete with their own proprietary colour corrector grading functionality.

I see both sides. I see the rationale that says, if we extend our open platform to secondary colours, it would be a powerful tool for cinematographers and filmmakers. The other side is, we’ve already achieved what it was originally intended to do. For most dailies colour grading, you don’t necessarily need to go beyond primaries.

But the functionality could expanded to include secondary colour. It wouldn’t replace ADC CDL v1; it would be an additional option.

If we do go down that path, that’s how it would be emphasised, because it’s not an attempt to compete with colour corrector manufacturers, and their comprehensive colour grading features that are essential for final colour grading.

BC: AMPAS recently introduced v1.0 of its Academy Color Encoding System (ACES), an open, device-independent colour management and image interchange system. Tell us about the committee’s involvement in this work.

CC: The committee has been involved for five or six years. The ASC has been a huge supporter of this, knowing the importance of having an open colour management system that is cross-platform and eliminates the ambiguities of secret sauce transforms. We are trying to get to one image interchange framework so everything is known. The workflow shouldn’t be broken; it should be a perfectly healthy workflow that has an understood and very powerful colour management system, and accommodates the widest dynamic range and colour space that the source material has. All of that should be preserved and utilised throughout the production chain, especially when colour grading.

Education has been an ongoing effort. There will be a more concerted effort, now that there’s an official version 1.0. There’s a perception that the official release of version 1.0, now makes it ready to use. Actually it was ready to use before it was an official release version 1.0, but since it now has the Academy’s official release imprimatur, it really is safe to go in the water.

On a personal note Sony Pictures and Tristar recently remastered Alamo Bay (1985). They did a 4K scan with ACES, ADX, full 16-bit colour. All of a sudden we were seeing colours and tones in the negative that I wasn’t able to see in the answer print. If I ever needed convincing about the importance of ACES, which I didn’t, this was a remarkable epiphany.

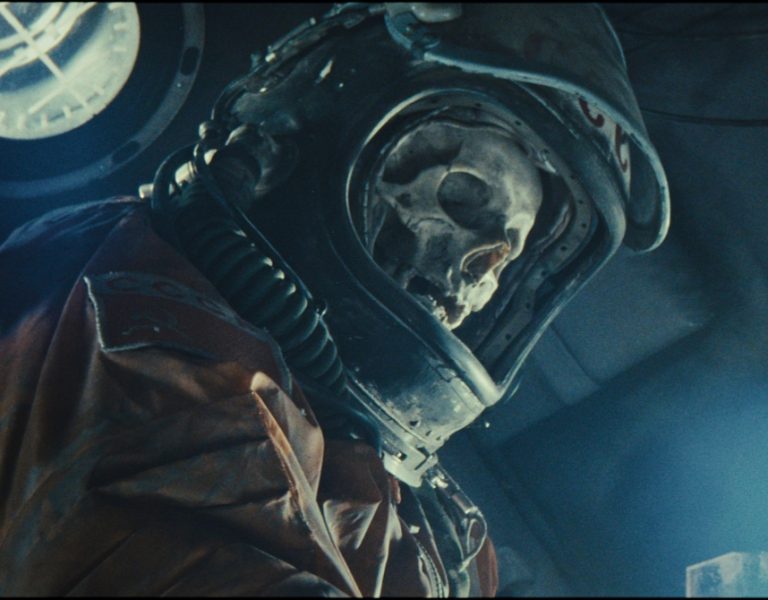

BC: You’ve been working in the field of high dynamic range (HDR) recently, and served as technical consultant on a short film, Trick Shot, filmed by Gale Tattersall with Canon’s new C300 Mark II. Tell us more…

CC: The Canon C300 Mark II is an excellent new camera that not only has a 15-stop dynamic range, but also outputs an exceptionally wide colour gamut with 4K resolution. There are two sides to the HDR coin – image capture and display. This means you have to capture an extended dynamic range of scene tones in the original image and then be able to properly reproduce it on an HDR display, which in itself can effectively reproduce that dynamic range at significantly greater brightness levels than are the norm with current standard dynamic range displays.

There is some controversy about what that optimum light level should be for HDR mastering with a professional reference monitor, which Dolby has been promoting at 4000nits. Others are saying maybe 2000nits is more practical for mastering. HDR consumer sets, when they come to market, will probably peak at around 1000nits.

Then you have to do a conversion or re-mastering to make it practical for distribution – to non-HDR formats. We used ACES in the final grade of Trick Shot to preserve the wide colour gamut and wide dynamic range captured by the C300 Mark II.

"It’s hard to find a production that doesn’t use the ASC CDL; it has become a de facto standard. Its flexibility is the secret to its success."

- Curtis Clark ASC

BC: What are some additional ASC Technology Committee initiatives?

CC: We currently have two, highly-active subcommittees. One is UHDTV, which is directly addressing HDR – clarifying what it means and how it can be used in a predictable and efficient way that best supports the filmmaker’s creative intent.

The other is a laser projection subcommittee, which is working to understand what can happen with laser-illuminated projection – both to increase brightness for HDR, and also to expand the colour gamut, because we know it will probably expand beyond the current DCI P3 digital cinema colour space.

What might that new standard be? We have put out a suggestion – we’re calling it practical primaries, based on a variation of the new Rec 2020 colour space proposal that’s part of the UHDTV agenda. We have an RFI (request for information) out to all the projector manufacturers, who are actively working with us on the committee, which should help us come to an understanding and agreement on what those practical primaries might be if they are not Rec 2020, but within the wide gamut colour space vicinity of Rec 2020. It doesn’t have to be Rec 2020, which was created for UHDTV broadcasting. Rec 2020 wasn’t created for digital cinema, though digital cinema is being influenced by it.

BC: A further subcommittee of the ASC Technology Committee is addressing virtual production. Could you give us an update on its initiatives?

CC: Our virtual production group has been hugely-successful. We originally had previs, which morphed into virtual production because it was difficult to separate the two. As we move more into the use of virtual production techniques, the importance of previs, especially for visual effects, has become common practice. But previs is also extending more into planning the entire film.

We are exploring tests and showcasing successful examples of the use of virtual production, as well as previs and postvis. It’s all merging into a new approach to filmmaking where we can integrate live action with CGI elements in a way that lets us better-manage creative intent, with efficiency.