Picture Framer

Clapperboard / Martin Hume BSC ACO GBCT

Picture Framer

Clapperboard / Martin Hume BSC ACO GBCT

BY: David A. Ellis

Camera operator Martin Hume was born in Cowley, Middlesex in May 1949. He is the son of the late Alan Hume (1924-2010), the notable cinematographer responsible for 102 features, including a great number of Carry On films, A View To A Kill, For Your Eyes Only, Star Wars Episode VI – Return Of The Jedi and A Fish Called Wanda.

Hume junior left school in 1966 and went to work in the Rank film laboratories at Denham. Being sporty, he wanted to become a professional footballer, but says he wasn’t good enough. Hume remained at Denham for around seven years, really enjoying the work.

So when did he move into cameras? “When at the lab I was asked by my father if I wanted to go into the camera department and I said I did. I took over a week off from the lab and went to Brighton, doing some training with Jimmy Devis on The Black Windmill (1974), starring Michael Caine. After that, my notice was handed in, because I realised I loved working with cameras. Then it was clapper loading for around eight years, moving on to focus pulling for seven years.”

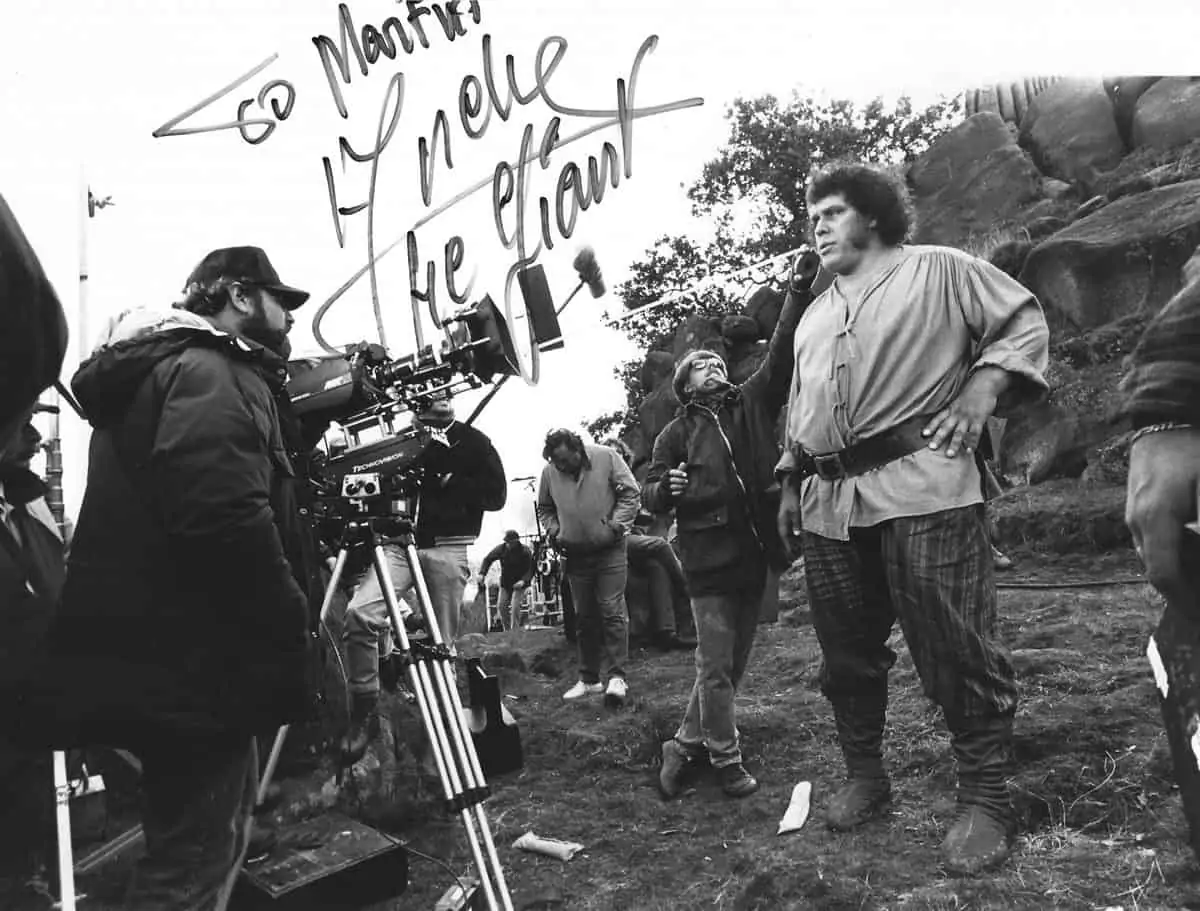

As well as focus he did some B-camera operating on Aliens (1986) with the late Adrian Biddle BSC. His last job on focus was The Princess Bride (1987), also with Biddle. His first film as main operator was Poor Little Rich Girl (1987) with his father and John Lindley as the DPs. Hume worked several times with his father and focus puller brother, Simon. Movies include Shirley Valentine (1989) and Carry On Columbus (1992), the last in the series. He said it was a hilarious experience. Director Gerald Thomas was marvellous and the working hours were good, 8.30am to 5.30pm with an hour for lunch. Usually a Carry On would be finished in six weeks.

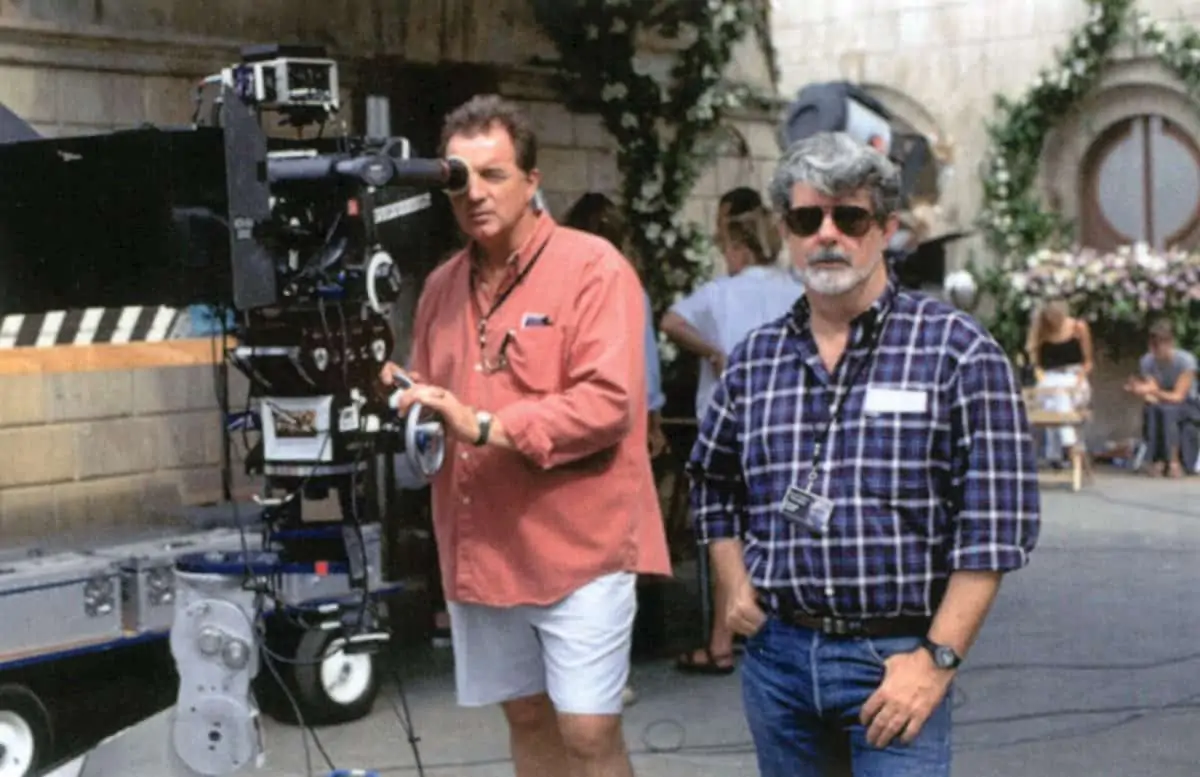

By contrast, Hume later went on to work with the mercurial Stanley Kubrick on Eyes Wide Shut (1999). Hume said, “Kubrick was very demanding, but to me he was very pleasant. On Eyes Wide Shut, we had various working hours. We worked from 10am to 10pm, then 12-12, 2-2 and finally 4-4. To me it was difficult because we had twenty takes on almost every shot. He didn’t want to see the camera move very much. Everything had to be very precise. It wasn’t done at a fast pace. Kubrick was very methodical. It was a difficult shoot and took fourteen months, but I am glad I got through it as it’s a feather in anybody’s cap.”

What advice would Hume give to aspiring camera operators? “Do your homework before you go on the set. Listen to the director and put what he wants in the picture framing to tell the story. You need to know what the subject is. You need to know what you will be doing that particular day; what section of the film and who’s doing what. You can’t just walk on and ask what are we doing today. Sometimes they might say, ‘we’re are not doing that, we have got to go and start from this other scene.’ So I would have to sit down and read it again. You also need to know the editorial side of things as well because of your eye lines, your crossing the lines and all that business.”

One of Hume’s biggest challenges was on the film Eve Of Destruction (1991), which Alan, his father, worked on as cinematographer. This was because nearly all the film was shot hand-held.

Hume’s industry heroes include directors Lewis Gilbert, Richard Lester, Richard Attenborough, Ridley Scott, Gerald Thomas and Kevin Connor. Camera operators and cinematogrephers include his father, Alex Thomson BSC, Ernie Day, Peter Macdonald, Freddie Cooper, Mike Roberts anf John Mathieson BSC.

If he could list only five films on his CV, they would be Eyes Wide Shut, because it was a challenging film and he worked with the great Stanley Kubrick. Kingdom Of Heaven, directed by Ridley Scott, because he regards Scott as one of the most amazing, visual and camera-orientated directors he has worked with. Next is Without A Clue, working with his father and brother. This is followed by Band Of Brothers, the TV series in which Hume worked on five episodes in 2001. Hume won the BSC Operators’ Award jointly with the late Martin Kenzie for Band Of Brothers. Finally, Shirley Valentine, during which Hume said he couldn’t stop laughing and the star Pauline Collins could see him shaking. She signed a photograph, which said, “I’ve never known an operator double up as a jelly.”

Hume feels that a lot of the humour and banter that took place is now missing from the film set. Looking back he says, “At one time it was very organised with not that many people. Today it’s like a cavalry going into a charge for twelve hours a day, six days a week. There are so many more people. In my day no one was allowed to walk in front of the camera – now when you start off in the morning there are over fifty people standing in the way while we are trying to do a line-up. They are all doing their bit, but I prefer the old ways.”

"My father’s shoes were big ones to fill. I was happy to remain as a camera operator as I like being up-front with the camera telling the story."

- Martin Hume

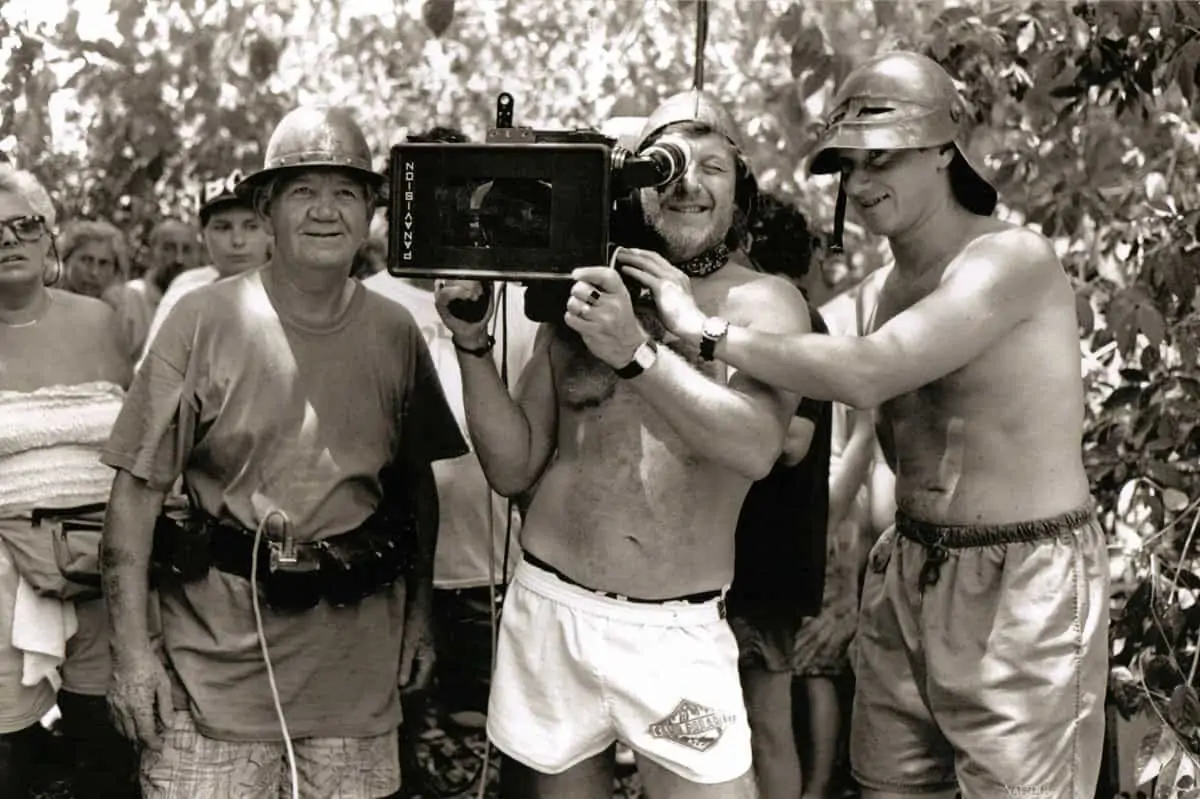

Asked about favourite places he has worked he said he enjoyed working in many countries around the world. He says he enjoyed Brazil on Moonraker (1979). Other locations include India and Jamaica, filming with the late Alex Thomson on Eureka (1983).

Hume would like to give a special thank you to: Jimmy Devis, Kevin Connor, the late Adrian Biddle BSC, Sean O’Dell and John Mathieson BSC for all their help and loyalty along his fantastic journey.

A number of the Hume family have entered the film business. Hume’s uncle Kenneth was a director and married Welsh singer Shirley Bassey. His elder brother was an editor who unfortunately died in a car crash aged twenty-one. His brother Simon is a focus puller. Simon Hume’s son Lewis is also in the business. Hume’s sister Pauline works as a movie and TV titles designer, working on many 007 James Bond features including Syfall (2012).

Hume is one of the founders of the ACO believing that camera operators should get more respect in the industry. Did he not consider becoming a cinematographer himself? “My father’s shoes were big ones to fill. I was happy to remain as a camera operator as I like being up-front with the camera telling the story.”

Asked how his father entered the business he said, “My father was in the Fleet Air Arm in the photographic unit. After the war he got a job at Olympic laboratories. He asked someone who was delivering the rushes from a film if he could have a look around Denham Studios. He became a clapper loader and eventually a DP.”

What does he think of digital cinematography? “To an operator it is no different. I would be sad to see film disappear; it is nice to have a choice. A lot of the cameras are lighter due to having no film, but some of the lenses are heavy and when placed on a small digital camera can cause imbalance.”

What are his interests away from film? “I have always been interested in sports of all kinds. At one time I would have played some of them but now just watch.”