Making Hay

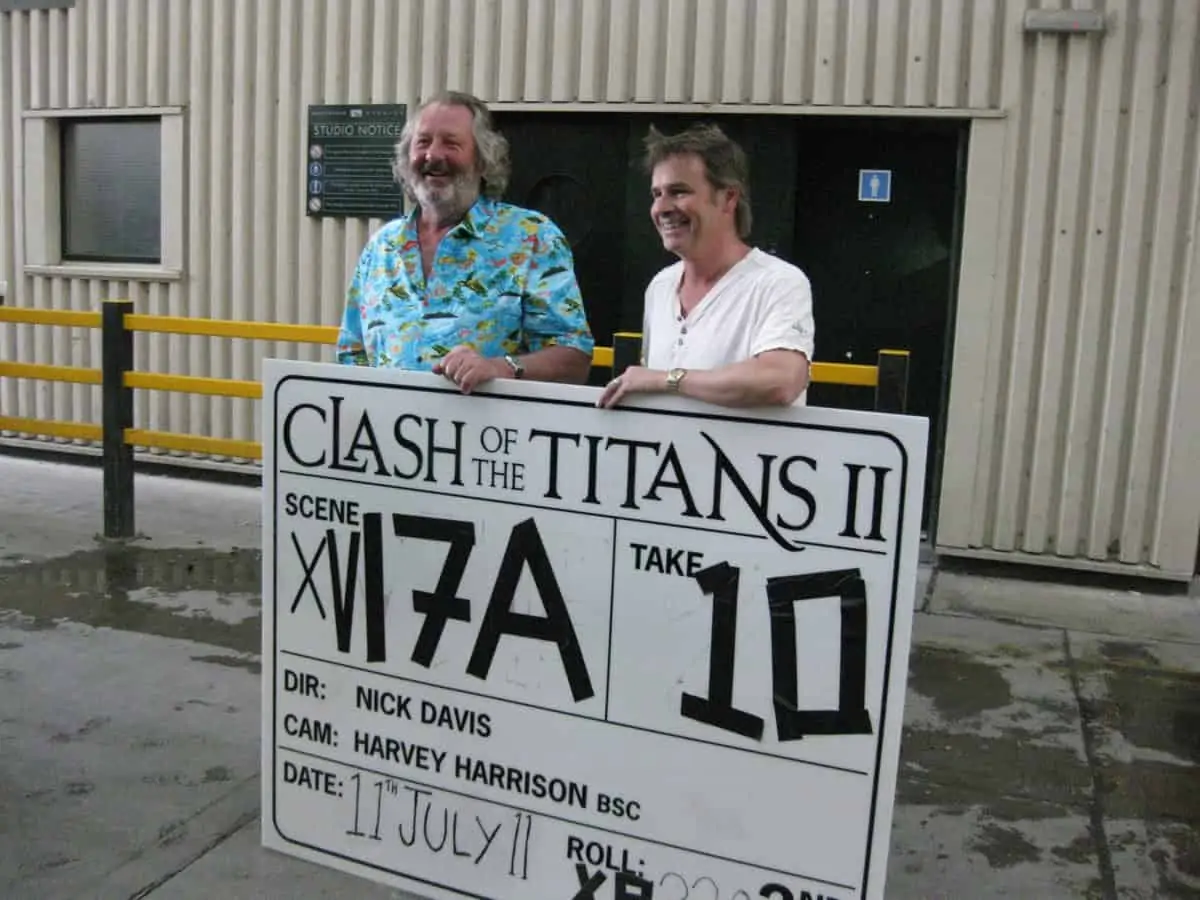

Clapperboard / Harvey Harrison BSC

Making Hay

Clapperboard / Harvey Harrison BSC

BY: Anwar Brett

Had things worked out the way he originally intended, Harvey Harrison would have spent his career toiling on a farm, rather than film sets around the world. Despite the fact that his father, Harvey senior, was a successful documentary cameraman and director, Harrison admits his rustic ambitions far outstripped any dreams he had of cinema.

“When I left school I started to work on a farm and I wondered if this was the life for me. I thought there must be more than that,” he recalls.

Born in London, but raised in the countryside of Hampshire and Wiltshire, his sudden change of heart was, in the end, inspired by the enjoyment his father had gotten from his career behind the camera. And that, above all else, is the key to Harvey Harrison’s long and fruitful career. He has shot all manner of productions, from commercials to major features, but the byword for making the day go faster and mood stay lighter is ‘fun’.

“I think if you don’t have fun then there’s no point in doing it,” he chuckles. “In my opinion it’s all got so serious now, the fun’s gone out of it. That was what I learnt working with people like Nic Roeg and Alex Thomson, again, having fun. And actually the last few pictures I’ve worked on have been fun too.”

The f-word is never at the expense of the f-stop however, as lessons learned early in his career in 1960’s Wardour Street have stayed with him.

“I was a clapper boy for a while, and then I became a focus puller for eight years; then an operator for another couple of years. And then I became a DP. I still believe that’s the right way to do it. I fear for the business in the digital age because, basically, anybody can get behind a digital camera and produce results. Gone are the days when we went through the mill, and learnt everything about the industry.”

The earliest experience Harrison gained was making documentaries with his father (“I was just his gopher, but he knocked some sense into me,”) before working as a clapper boy under Billy Williams BSC at pioneering commercials company TVA – a neat symmetry, as Williams’ dad had worked as cameraman for Harvey’s father during the war.

“Once I found my feet there I realised that the world was up for grabs,” says Harrison. “It was just up to you to really go for it. We’d have two or three productions being shot at the same time in those days, one day shoots. This was in 1961 – in B&W. Colour came in pretty soon afterwards, but in my formative years it was all B&W.”

TVA proved a fine finishing school for Harrison, enabling him to watch some great cameramen at work, visiting DPs such as Geoff Unsworth BSC, Freddie Francis BSC, Gil Taylor BSC, Denys Coop BSC, Nic Roeg BSC and Alex Thomson BSC.

“I spent a long time focus pulling for Alex Thomson, and some of the things I learned from him were absolutely supreme. Particularly how to treat people, and how to run a floor. And, of course, how to do your job and light and get the best out of everything.”

Many years later Roeg called upon Harrison to light his 1986 feature Castaway, the true story of an eccentric adventurer (played by Oliver Reed) who advertises for a companion to share an island paradise with him. But when Lucy (Amanda Donohoe) signs up for this dream job the nightmarish reality soon sets in. For Harrison the thrill of working alongside one of his cinematic heroes on a feature, after making many commercials with Roeg, brought with it its own set of pressures.

“Nic was great, I did three pictures with him over the years, and he always left you to it. Sometimes you’d say ‘Okay Nic, I’m ready,’ and he’d come up to the camera, look at the set and then turn to you and say, ‘Well Harvey, I suppose if that’s it, we’d better shoot’. At that point you knew damn well that you’d missed something that he’d picked up on.”

"Once I found my feet there I realised that the world was up for grabs, It was just up to you to really go for it."

- Harvey Harrison BSC

The qualities of a good cinematographer, in Harrison’s view, include the ability to deal with such situations and remain calm at all times. He certainly gives the impression of being ruggedly imperturbable, the kind of head of department who inspires an unwavering loyalty in his own crew. Many of Harrison’s have been with him for years, the likes of operators Peter Taylor and Gary Spratling; focus pullers Mike Evans and Kenny Groom; gaffer Steve Foster and grip Kenny Atherfold.

“He’s a big loveable bear,” says Atherfold, “and he knows every aspect of filmmaking. But he trusts you too, that’s why he employs you, because he knows you can do your job and, by doing that, complement his work.”

This fruitful atmosphere of mutual trust can be helpful when problems arise and a degree of ingenuity is required.

“Freefalling we call it,” adds Atherfold. “He comes up with an idea and we just make it work for him.”

“We’re always knocking something up,” Harrison agrees. “I’ll say, ‘Well look Ken, we need to put a camera here or there,’ and most people would look at you and say, ‘You’re nuts, you can’t do it’. But Ken says, ‘Don’t worry mate,’ and in five minutes we’ve got the camera where we want it, and off we go.”

A winning blend of technician and artist, Harrison’s most prized piece of equipment remains a pan glass he has had for 40 years – “I still use a B&W one. I find it much easier to judge contrast with it,” he says.

In more than 50 years behind the camera he has shot commercials, concerts, five World Cups and five Olympic Games, small independent films and major movies. As well as Castaway he counts shooting second unit for Adrian Biddle on the 2005 film V For Vendetta (one of eight films they worked on together) among his favourite assignments, as well as shooting second unit on GoldenEye ten years earlier for second unit director Ian Sharp.

“We saw eye-to-eye on just about everything,” Sharp recalls, “it was a very, very happy working relationship and led to us doing two or three other films together.”

Along with many memorable action sequences, the most arresting iconic shot of GoldenEye was the pre-credit sequence that involved 007 (introducing Pierce Brosnan to the role) doing a swan dive off the towering Verzasca Dam in Switzerland, attached to a bungee cord. For such a major set piece stunt, Harrison insisted on operating himself to save his crew from any comebacks should there be mishaps or problems.

“I said to the stuntman Wayne Michaels that it was absolutely vital that he pull his gun,” Sharp adds. “And Harvey followed him all the way down, absolutely perfect, right on the crosshairs. It was a brilliant piece of camerawork.”

It’s where artistry meets technical excellence, a fine line that not every cinematographer manages to walk, but Harrison takes it in his long, loping stride. Over the years his passion for the job has seen him serve terms as president of the BSC and IMAGO, and chairman of the GBCT, so the desire to give something back is strong within him.

But still, there is nothing that beats getting on location and facing the challenge of another day’s shooting. Preparation is essential, a lighting plan and a thorough knowledge of the screenplay; “When somebody asks you, ‘What happens after this?’, you can’t be flapping around thinking, ‘Hang on a minute, I’ll look at my notes’. It has to be in your head.”

The relationship with Ian Sharp notably continued in the 2010 drama Tracker, a powerful character tale with gripping action, shot on location in New Zealand. “That was a hard picture physically, but wonderful fun,” Harrison notes, “with Ian directing and the actors Ray Winstone and Temuera Morrison – they were all fantastic.”

Ray Winstone, a veteran these days of many a major Hollywood production, is quick to praise Harrison’s approach to his work.

“I think we feel so lucky to have a job we like doing, and when you turn up every day and look forward to it, that has a lot to do with people like Harvey and Ian Sharp. On Tracker you could see the whole crew enjoying the job, and that comes from the top. The top is always the director and the DP, and it’s a sign of people who are very good at what they do.

“The way Harvey shot New Zealand, and the way he incorporated it into the story, you realised you were working with a guy who really knows his stuff. One of the last shots we had, the final scene in some waterfalls in the mountains, on the day we had to film there it was overcast. On a great day the sun would have been out and you could have seen the full beauty of the place.

“But everyone was gutted because this was the shot the whole film had been gearing towards. And Harvey was just, ‘What will be, will be,’ and you knew he’d make good of it. And he did. In a way the harshness of the weather kind of worked for the scene, perhaps if it had been a beautiful day it wouldn’t have looked so great, it would have looked too glossy. But nothing fazes Harvey, and if it does he doesn’t let you know it. It doesn’t get in the way of what you’re doing.”

Even as Harvey Harrison reaches veteran status himself, the physical challenges remain key to the enjoyment he derives from the job, whether shooting in the Sahara or the Arctic, southern hemisphere or a soundstage at Pinewood. In the past few years he shot second unit for Sylvester Stallone on his latest foray as Rambo (2008), as well as on The Wolfman (2010), Wrath Of The Titans (2012) and most recently Red 2 (2013). And the job remains as enjoyable as it ever did. Even as film gives way to digital, the qualities of a great cinematographer – qualities Harvey Harrison possesses in abundance – remain eternal. Farming’s loss is cinema’s gain.