Ciara Rigney discusses her NFTS graduate film Weekend One, exploring fatherhood, intimacy and naturalistic visuals, inspired by Eugene Richards’ and Sophie Harris-Taylor’s work.

Weekend One follows a father navigating hardship and emotional vulnerability.

British Cinematographer (BC): Please can you share an overview of your film?

Ciara Rigney (CR): Weekend One, tells the story of Amari, a father facing hardship as he relocates to an empty apartment with his two young sons, Kieran and Jamal. Struggling with feelings of shame, financial uncertainty, and the weight of fatherhood, Amari is determined to become the strong role model his children need.

BC: What were your initial discussions about the visual approach for the film? What look and mood were you trying to achieve?

CR: When the director, Mykea Fairweather Perry and I first began breaking down the script, we knew that the heart of the project lay in its raw, emotional intimacy. That the connection between the audience and the story had to feel personable and real in order to truly resonate. For me, it was important to ensure that this sense of intimacy was not only preserved in the visuals but deeply embedded throughout the narrative. We wanted the viewers to feel as though they were right there with the characters, experiencing their challenges first-hand. We needed the location & visuals to feel as bare to the audience as to the characters, reflecting Amari’s isolation and the emptiness in this new world. To make every moment feel authentic, and to allow the audience to connect with the story on an emotional level that went beyond just watching a film.

From the outset, we were clear that we wanted the film to lean towards naturalism, in line with both the script’s intentions and the scope of the project but not feel overly formulaic or archetypal. Instead, we sought to create something that felt grounded and authentic, while still allowing room for a more nuanced artistic expression. It was crucial to us that the film felt real but also visually compelling.

BC: What were your creative references and inspirations? Which films, still photography or paintings were you influenced by?

CR: The director and I often drew from Eugene Richards’ photography series Dorchester Days. His work captures the raw beauty and harsh realities of everyday life, it allowed me to slow down and notice the quiet moments in the script that carry the most meaning. Richards’ photography doesn’t rush; it allows space to breathe, revealing deep emotional textures in simple, unguarded moments – something we strove to achieve in the film. Much like Richards’ images, I wanted to capture vulnerability and resilience in the small, overlooked details—whether it’s a fleeting glance or a quiet exchange.

Similarly, the work of Sophie Harris-Taylor in Present Father inspired our visual language. Her photography reflects the heart of our film, which explores the complexities of fatherhood, connection, and struggle. The quiet moments in her images, where light and shadow interplay to paint relationships, are heavily drawn upon in this film.

Both Richards and Harris-Taylor taught me the importance of patience in storytelling—letting the moments unfold naturally without forcing them, and capturing the profound meaning in everyday exchanges.

BC: What filming locations were used? Were any sets constructed? Did any of the locations present any challenges?

CR: Our locations included an apartment, car, parking lot, a furniture store and a grocery store. The script’s biggest location challenge came from much of the narrative unfolding within the confined space of a car and an empty apartment. Finding the perfect car was essential, not only to reflect the characters but also to allow for versatile shooting. We needed a vehicle that could support a variety of scenes, accommodating both intimate, close-up sequences and dynamic movements. Similarly, the hunt for the right apartment was critical, not only from a logistical production standpoint but also in capturing the essence of Amari’s journey. The director was invested in finding a space that resonated with the character’s struggles, while I had to ensure it could be lit effectively. The apartment needed to offer practical elements, like wide windows for natural light, with such windows at a reasonable height so we could light through them!

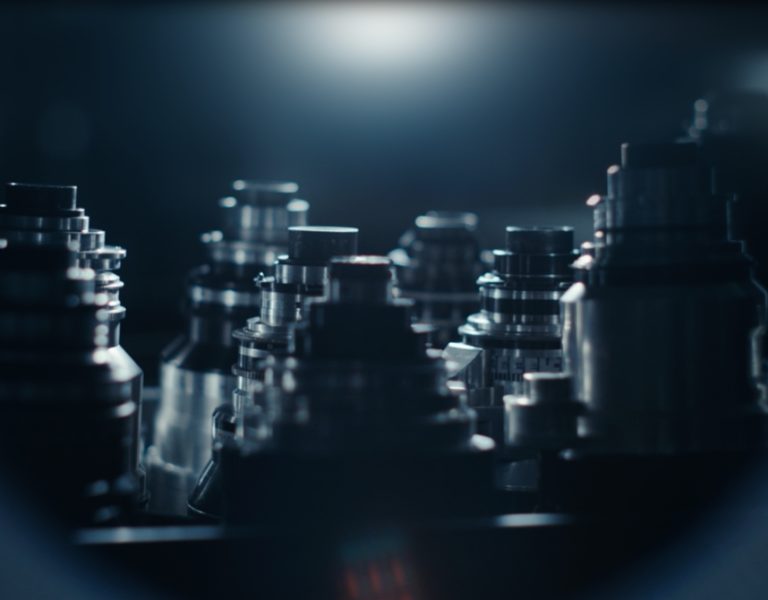

BC: Can you explain your choice of camera and lenses and what made them suitable for this production and the look you were trying to achieve?

CR: After lots of testing, I decided to go with the ARRI Mini LF with Canon K35’s and a 58mm Petal lens. The Mini LF’s compact size and large-format sensor gave us the flexibility to shoot in tight spaces like the car and apartment, while still providing the cinematic depth and texture the story needed. Its dynamic range was key in capturing both the darker, emotional moments and the bright, natural light in high key scenes. The K35 lenses added a soft, vintage quality that gave the film a warmth, helping us balance the harshness of the LF sensor. Meanwhile, the Petzval lenses, with their unique swirl and soft-focus, created a nostalgic, intimate feel that we felt if used correctly could mirror the characters’ emotional journeys – in coming from the familiarity of London and moving into the uncertainty of a suburb.

BC: What role did camera movement, composition and framing and colour play in the visual storytelling?

CR: We chose to rely heavily on handheld camerawork throughout most of the film to bring a sense of vulnerability and immediacy to Amari’s experience. The slight instability of the frame mirrored his emotional state—his struggles as a father, his uncertainty, and the weight of his circumstances. The camera was always with him, breathing with him, allowing the audience to feel deeply connected to his world. However, as the story reaches its final scene, we made a deliberate shift. For the first time, we moved to static shots, visually representing a sense of grounding for the family. By holding the frame steady, we reflected Amari’s quiet acceptance and newfound stability, however fragile it may be. This contrast between movement and stillness reinforced his journey, making that final moment of acceptance all the more powerful.

BC: What was your approach to lighting the film? Which was the most difficult scene to light?

CR: Natural light became a starting point for myself and gaffer Suzzette Ortiz, especially within the apartment, where we had large windows that could fill the space with soft, diffused light. I wanted the film to feel grounded in reality, so I used the daylight as much as possible, allowing it to pour into the apartment and illuminate the characters in a way that felt organic. We relied heavily on the changing quality of natural light to reflect the emotional shifts in the story—whether it was the warm, golden light of the morning or the colder, more subdued tones of the evening. This meant the schedule had to be very closely watched for sun path. That said, the challenge was to shape this light in a way that didn’t feel uncontrolled or overly harsh, which is where the meticulous shaping and augmentation came into play.

With the apartment having mostly white walls (something which felt daunting when I first read the script), controlling the natural light became very important. To solve this, we hung large black negs on every surface not visible to the camera, which allowed us to control the light’s bounce and focus the illumination where it was needed. The space was difficult to light because of its emptiness— there were no natural objects or structures to absorb light or cast shadows, so we had to be very intentional with every decision. Getting the correct skin tone was incredibly important to me; I wanted to ensure that the warmth of the characters was present, but I also didn’t want the light to feel too soft or diffused, which can sometimes wash out the texture of the skin. The entire process was intricate and required constant adjustments, which was a delicate balance, but with the help of my gaffer and the incredible electrical team, we were able to get the light to sit just right!

Ultimately, my goal was to ensure that the film was lit in such a way that it felt sculpted but never artificial. Every lighting decision was made to support the emotional narrative, and the challenge of working with a bare, white apartment only heightened the importance of careful light control. The light had to feel as much a part of the environment as the characters themselves, existing in the same space, shaping the mood without drawing attention to itself.

BC: What were you trying to achieve in the grade?

CR: In the grade, my main goal was to fine-tune the visuals in a way that deepened the storytelling while keeping the film’s natural, lived-in feel. I wanted every frame to feel honest and grounded, enhancing the emotional tone without ever making it look overworked or stylised. The colours were to feel rich and evocative, yet still true to the world we created. It needed to maintain its authenticity, but at the same time, I wanted it to feel cinematic and immersive. I am incredibly thankful for my colourist, Ellen Yu for her expertise and collaboration throughout the grading process. We worked together closely to make sure the grade served the emotional core of the film. Our primary focus was on ensuring the skin tones were true and consistent, maintaining that warmth and depth that were so integral to the characters’ journeys.

In scenes where Amari’s internal struggle was most intense, we really leaned into contrast, making the lighting feel more sculpted and intensifying the emotional atmosphere. The subtle deepening of shadows allowed us to bring a sense of isolation and vulnerability. We were careful not to make the look too stark or heavy-handed, but instead allowed the grade to work with the natural rhythms of the film, creating a visual language that complemented our rushes.

Overall, the aim was to create a grade that felt natural (without being dull), and emotional (without being overly dramatic). It was all about finding that sweet spot where the visuals and the story could come together to fully immerse the audience in the journey of the characters. With Ellen’s incredible skill and understanding of the vision, I’m really proud of what we achieved together in the grade.

BC: Which elements of the film were most challenging to shoot and how did you overcome those obstacles?

CR: One of the most challenging aspects of the production was the three full days spent shooting in a cramped apartment, with all crew stacked one on top of the other. The tight space and intense schedule required a lot of careful planning and coordination. After that, we moved into our final shooting days, which involved multiple locations, and finding the right flow during this change for the set became crucial. It was a balancing act to ensure that the team knew exactly what was coming next, so we could all work efficiently and to our full potential. The pace was rigorous, but through clear communication and a unified approach, we were able to navigate these location moves and maintain the film’s core while keeping the production moving smoothly!

BC: What was your proudest moment throughout the production process or which scene/shot are you most proud of?

CR: My proudest moment from the production process was undoubtedly the feeling of camaraderie and collective effort that ran through the entire crew. There was something incredibly special about the way everyone came together, mucking in and fully committing to making the film. Whether it was a challenging shot or a long day during prep, the energy was always one of collaboration and shared passion. I’ll never forget the moments when we nailed a particularly difficult shot and I could look around to see everyone’s faces light up with pride and satisfaction. In those moments, I felt deeply grateful to be part of a team where every person—whether in lighting, camera, or any department— had the same goal: to make the best film possible. It was that sense of unity and purpose that made me feel proud to be part of something bigger, knowing that everyone was giving their all to create something meaningful.

BC: What lessons did you learn from this production you will take with you onto future productions?

CR: One of the biggest lessons I learned from this production was the delicate balance between preparation and being able to react in the moment. We spent a lot of time meticulously planning every detail, from lighting to camera movement, but as always the true curveball comes when you have to adapt to what is unfolding right in front of you. Especially working with two amazing young actors, Azariah Gray and Maxwell Smith, their performances were so dynamic and authentic that we had to remain flexible to allow their natural energy shape the scenes. The rawness and immediacy of their work often led to moments we hadn’t fully anticipated, and it became clear that the most important thing was staying responsive to what was happening on set. Allowing the film to breathe and evolve in real-time. Moving forward, I’ll carry this approach of thorough preparation coupled with the freedom to react to the unpredictable nature of filmmaking, ensuring that future productions maintain that same sense of spontaneity, authenticity, and emotional depth.