QUEEN OF THE SCREEN

She was one of the brightest lights of the Golden Age of Hollywood, but Marilyn Monroe’s troubled private life was equally in the spotlight. Chayse Irvin ASC CSC explains how he revived Monroe’s star power in his cinematography for Blonde.

Blonde charts Norma Jean Baker’s transformation into screen icon Marilyn Monroe from childhood trauma through a series of abusive relationships and culminates in her fatal overdose.

Described by director Andrew Dominik as “an emotional nightmare fairy-tale” this fictionalised account starts and ends with Monroe’s relationship with her absent father and mixes familiar iconography into a disturbing mental horror.

“Andrew wanted an avalanche of images depicting Marilyn’s life,” says Chayse Irvin ASC CSC (BlacKkKlansman). “That idea helped me understand what he was trying to achieve aesthetically. Ever since childhood she has had a disconnecting experience with her mother, then the orphanage, then finding fame in the film business. This chaotic existence where she is constantly torn in multiple directions.”

Although there are numerous recreations of Monroe’s life and encounters with rich and powerful men, the Netflix film, like Joyce Carol Oates’ book from which Dominik’s screenplay is adapted, is a study in psychology.

“Andrew had a real understanding of what he was trying to do emotionally – but he would take it multiple directions during a scene,” says Irvin. “He was constantly changing it to create a library of emotions so that in the editorial process he can create rhythms or ripples of those emotions that then reflect each other across the film.

“At the core, Andrew wanted Blonde to feel like a séance. As if by recreating these images we are resurrecting her soul. I loved the idea that we’re taking some very well-known images and building scenes around them to create an eerie, uneasy feeling.”

Formally, the filmmakers shot with alternating aspect ratios, but mostly 1.33:1 which emulates portrait and magazine photography of the period. The square frame not only dictated the central positioning of actress Ana de Armas in many shots but also shallow depth of field.

“The real metaphor we were going for was fragility. When the focus is that shallow it feels like teetering on the edge of falling apart. That is what we wanted to connect with.”

At one point the frame is vertical in recreation of an actual still. For this shot Irvin rotated the camera 90 degrees.

SUPPORTING THE STAR

Although 35mm seemed the natural choice and was Irvin’s initial leaning, they chose digital in order to support de Armas on set.

She trained for nine months with a dialect coach to perfect Monroe’s high-pitched timbre, hard enough for anyone with English as a second language. Since the coach would be working on set with the Cuban actress to shape every word she spoke as Marilyn, it was decided that the flexibility of a digital format would best enable the multiple takes required for her voice performance to be finessed (using ADR) in editorial.

That early decision led Irvin down a rabbit hole of video camera tests. “We talked with ARRI at length about manufacturing a monochrome version of the LF Mini but in the end they felt uneasy about it. They’d had such an overwhelmingly positive response to LF Mini orders it wasn’t possible to accommodate our film.”

Instead, Irvin staged multiple scenes with stand-ins shooting Sony Venice and ARRI Alexa XT B+W in a blind test for Dominik.

“We shot the sun going down to see how quickly each camera would react to focus pulls and took the sequences to EFILM for identical grading and halation before screening for Andrew.”

In the first set of test images Dominik preferred the Sony. But in the second he preferred the ARRI. They still couldn’t decide, so they used both.

Colour scenes are shot on Venice but so too are many monochrome ones, processed from a BW LUT. Other scenes are shot on the Alexa XT which has a modified sensor (no Bayer mask, optical low-pass filter, or IR block filter) capable of producing images that look much like 35mm panchromatic film. The camera is also more sensitive than a regular Alexa, with a native sensitivity of around EI 2000.

“We never wanted to blend between the two, not so much aesthetically but because we didn’t want to be waiting on camera.”

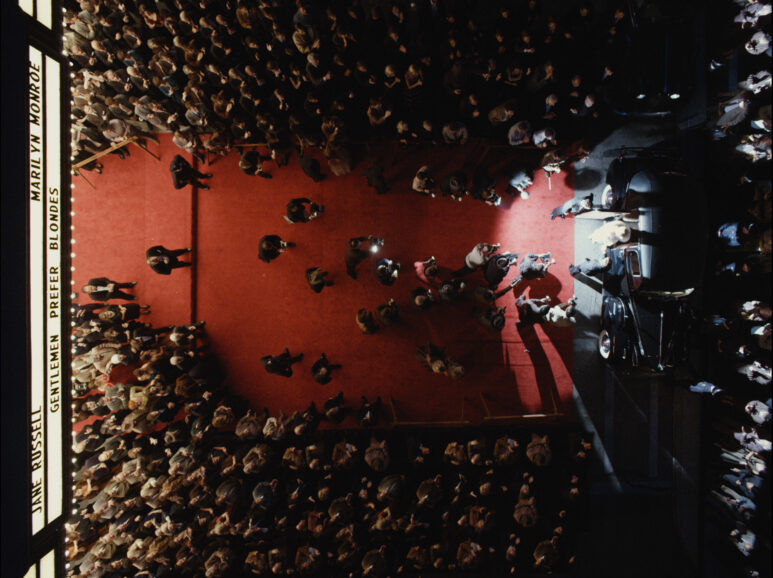

The Venice was quicker to set up and go for scenes with fast camera movement or multi-cam built onto dolly, Steadicam or otherwise rigged, such as the recreation of the skirt blowing sequence from The Seven Year Itch. Irvin was also able to quickly grab a Venice to mount onto a condor and take an overhead shot that was used a couple of times to depict Monroe surrounded by a baying mob at a film premiere.

Both cameras were Panavised at Panavision LA who also supplied the principal set of PVintage Primes based on Ultra Speeds, selected in part because of the “spontaneity” of not having to deal with technical challenges such as different front diameters or matt box rings.

He specifically relied on T1.0 50mm, a focal length often used in stills photos of the period, but which also gave him “supreme control over depth of field” when he needed to go even shallower. Cmotion Cinefade was used on every shot as a variable ND filter rather than to manipulate depth of field.

The Venice was used in Rialto mode for first person shots attached to actor Bobby Cannavale (playing Joe DiMaggio) and on de Armas, the first when DiMaggio flies into a rage and the second when Monroe collapses from being injected with drugs.

Several sequences were shot infra-red on Alexa XT including a startling scene when Monroe wakes up in the middle of the night in her apartment. Irvin purchased infra-red security lights from Amazon mounted to the camera and shot in pitch dark.

“The Steadicam follows Ana who is blindly looking through the house with secret service men lurking in the room and it illuminates these weird textures like the veins in her neck.”

INSPIRED BY THE PAST

Although the narrative shifts through the three decades of Monroe’s life, Irvin used one staple colour LUT. The main colour alteration was in emulating Technicolor including for frame accurate recreations of classic like Gentlemen Prefer Blondes and the trailer for Niagara (both released 1953).

For Niagara, colourist Tom Poole used hi-res images taken from Blu-ray as the basis for look emulation. In Blonde, Marilyn is shown watching her films in front of packed cinema audiences. On set, the recreated scene was projected for real on the theatre screen with the projected images played back on Irvin’s laptop through Resolve.

“This would allow me to see the monitor of the actual camera shooting the scene and at the same time to grade the projection. Otherwise, it would look blown out and you’d end up having to composite the image in post. On set the image looked unwatchable but, on my monitor, it looked like it should based on the renders Tom had made to emulate Technicolor.”

He worked with production designer Florencia Martin and costume designer Jennifer Johnson to develop colour mise-en-scène. The palette is soft: pink, blue, fawn, grey, white, to evoke fragility. “Flo would make tones and hues for reds, blues and we tested them to see how the LUT would react.”

Time and again, Irvin stresses that Dominik’s approach to this film chimed with his own philosophy which is not to overthink or calculate but to intuit a shot organically.

“Sometimes, working on a film, I feel I am speaking a message but when you work this way it’s more like you are receiving. You have to make yourself vulnerable to forgo preconceived ideas and admit that you don’t know the answers, but you have to be alive enough to capture the moment when it arrives.”

Achieving this was a challenge for his crew. The DP relied on focus puller Jimmy Ward, with whom he had first worked on music videos. “I call him Jimmy One Four because when we worked on that music video shooting T1.4 not a single frame was out of focus. Whereas I like to stay in the moment, Jimmy is one step ahead prepping for the next thing.”

Also credited by Irvin is the support given by additional first assistant Sean Kisch for prepping cameras and cmotion, while with Steadicam Dana Morris, Irvin shared operating duties.

FORWARD THINKING

Cody Jacobs is Irvin’s regular gaffer who, like Ward, plans ahead to let the DP concentrate on the scene at hand. Irvin admits to finding lighting a challenge. “I love coming up with the strategy and devising schematics, but for executing that and making fine adjustments I need people like Cody and rigging gaffer John Manocchia and technician Jerry Gregoricka. Whereas for some grips lighting is a process of engineering and it becomes overcomplicated, I like to work with a crew who have confidence in their ability to change things in a simple way.”

He elaborates, “I don’t really know what I want until I see it so I’m constantly making pivots. I really try to protect the special process of blocking and using that as a sacred creative space. It’s the first time I discover the scene. You can do all the lighting design in the world but only when I am responding to the scene can I understand what I need.”

For Blonde, they employed a lot of top lighting or motivational light from windows or more powerful sources from distance. Close-ups were augmented with LEDs or smaller battery-powered fixtures.

The opening act depicts a fire in the Hollywood hills all but engulfing the Baker family home as Norma Jean and her mother flee by car. The exteriors were shot on location for which Irvin used Christmas lights and baton strips as a base for VFX to create flames.

“The lights reacted to the optics, so we didn’t just have a 2D comp of the fire,” says Irvin. “The fire scenes in Baker’s home are done the same way.”

While at this location they shot high resolution plates using an array of Nikon 5D cameras so that single shot interiors of the car (with smoke and fire augmented by VFX) could be filmed on Netflix volume stage. This was done to maximise the on-set time of child actor Mia McGovern Zaini playing the young Norma Jean.

“Those singles on the LED stage matched perfectly. We’d worked out in prep how this would look, and I learned a lot from being on the stage. Our rationale was that filmmakers of the period were using rear projection so using a volume felt in keeping with that.”

A later scene of Monroe being driven by special agents to see JFK in New York was also filmed in a volume using archive VistaVision plates projected to recreate the gleaming black and white city at night.

The finals scenes of Marilyn’s death were shot in the actual apartment and bedroom where she had lived and died.

“Those three days were very strange for all of us. The whole crew paused and thought of her, and I always felt a presence in the house. You knew that she must have been grieving. When she bought that house, it was a new beginning and it ended in tragedy.”