SOUNDS OF THE UNDERGROUND

Fresh from his Bafta Television Craft Award success, Chas Appeti, the cinematographer and co-creator of Amazon’s Jungle with Junior Okoli, reflects on his winning work on the innovative musical series.

Tinie Tempah, Big Narstie, Unknown T – just some of the stars of the UK’s rap and drill scene who you’ll spot in Amazon’s Jungle, a musical series that pushes both creative and lyrical boundaries. Set in a near-future British city (the eponymous Jungle) and oozing with neon and noirish flair, the series fuses dialogue and music to create TV’s first drill musical, led by a medley of music artists and actors.

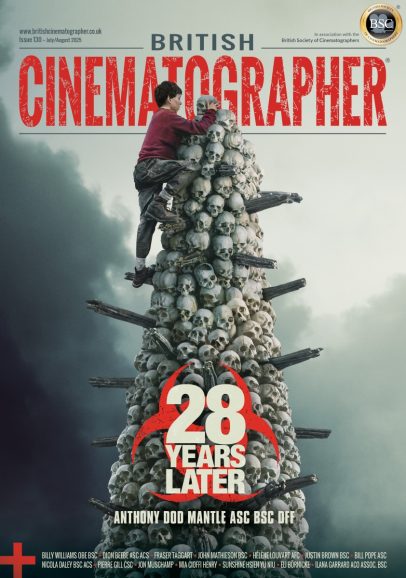

Bafta voters were so taken with Jungle’s cinematography that its DP and co-creator, Chas Appeti, scooped the Television Craft Award for Best Photography & Lighting: Fiction, against stiff competition from Anthony Dod Mantle DFF BSC ASC, Ben Wheeler BSC and Rachel Clark.

“I honestly didn’t expect it,” the DP admits. “Junior [Okoli] jumped in and saved the day, and I managed to say what I had written down on a little bit of paper. Seriously, I was happy enough to be nominated; that was a privilege enough for me.”

It’s an impressive feat for his episodic debut, and recognition of a lifelong love for visual storytelling. A childhood love for art saw him become a graphic designer aged 17, and he later progressed into photography alongside making music.

“I didn’t mean to start shooting,” he says with a wry smile.

But when a friend’s younger brother needed a music promo, Appeti was a natural candidate. He quickly gained a reputation for his music video shoots and became one of the go-to cinematographers for the UK rap scene over the past decade, with over 2,000 videos to his name.

It’s through his musical background that he met his “creative sidekick”, Junior Okoli, a music manager turned writer-director of Jungle, and they founded creative agency Nothing Lost together in 2017.

“You don’t really meet a lot of people in life who are exactly on the same page as you – your taste and visuals, and even morals,” he muses.

Jungle is centred around young Gogo (Ezra Elliott) who’s hoping to escape his criminal lifestyle now he’s set to be a father. Appeti and Okoli shot a Drive-esque pilot for the series over just two days with a skeleton crew of five, including the two creators.

They used the ARRI Alexa Mini and Zeiss Super Speeds on this initial episode: “I wanted to have that warmish tone to the lens and a little bit more bokeh on it,” Appeti says.

Although the DP says the world will sadly never see the pilot, the team at Amazon US, however, did see it – and were blown away.

“They loved it and didn’t understand how we did it,” he remembers. “They said, ‘Do you mind if we show the UK team?’”

Then-head of UK scripted, Fleabag exec Lydia Hampson, and then-head of Amazon Studios in Europe, Georgia Brown were as equally transfixed as their US counterparts and within 10 weeks, Jungle was greenlit for the UK.

Screen artistry

“Our mission statement before we started was basically, if you could take any frame of Jungle, you could stick it on the wall and have it as a picture.”

Some might say it’s an ambitious target for your first long-form project, but Appeti was never fazed by the prospect of moving from promos to television.

“Everyone would say, are you not scared about moving from promos to long-form and I’ll be honest, I was never scared,” he remembers. “It was just a bigger canvas to paint.”

When crewing up, he drew on talent that he knew and trusted from his music video days. As with the pilot, he and Okoli liked to keep the team compact.

“We like to keep the crew pretty tight, in terms of who’s around the camera and the decisions that are being made. We’re quite meticulous when it comes to how it looks,” he adds.

Principal photography spanned eight-and-a-half weeks in summer 2021; “completely the wrong time of year,” Appeti says. “It’s set mostly at night-time and ideally we should have shot in the winter for the longer nights.”

Unlike the pilot, they opted for large format cameras from Procam for the series – two Mini LFs and another Alexa LF, to allow them to shoot up to 100 frames per second but with the same sensor. Some of Jungle’s defining sequences involve some intricate slow-motion capture, for which Appeti brought in the Phantom. “Anything shot at 1,000 frames per second was shot on that, then we tried to match with the sensor in terms of tone or lighting.” The cameras were paired with Signature Primes, and Black Pro-Mist and Glimmerglass for filtration.

Appeti operated A-camera, with Steadicam and Trinity operator Sébastien Joly ACO on B-camera. For the DP, getting to operate is part of his image-making philosophy.

“Being hands-on with the camera is important in my eyes because you can have an operator, but they’re still not going to quite put the camera in the position you’re trying to explain to them,” he comments. “It can by easier just to do it yourself. Obviously, you get some amazing operators, but in my opinion it’s just quicker to do it yourself. I’ve got a good team around me, so when something works well, you don’t really want to change it.”

When it comes to his camerawork, the cinematographer is a staunch advocate of not moving the camera for the sake of it; any movement must have a clear reason behind it.

“Our narrative scenes are a bit more like traditional cinematography and framing,” he says. “The music video scenes had to be more energetic in terms of both camera movement and the edit. We’re very big advocates of not doing fancy shots or dollies – or any movement if it’s not necessary. If you just chuck in loads of [those shots] it dilutes it a bit. Everything in Jungle has got its place and has been thought about.”

When crafting Jungle’s stylised, often neon lighting, Appeti worked closely with gaffer David Witchell. Compared to his short-form work, the lighting process was very similar but involved a lot more recces.

“That was really important, the recceing and the technical side of it, in terms of knowing what we’re going to execute on the shoot days and what was going to be needed,” the DP says. “Things would change a little bit on the day, but the overall vision was pretty much done before we stepped on set every day. In my eyes, [the move to long-form] wasn’t that daunting because we could pre-light a day before if we needed to.”

Around 90% of the lights were LEDs, and the team opted for a lot of smaller lighting setups. Appeti remembers they had around 90 of Aputure’s remote-controlled MC box lights, which were useful thanks to being both lightweight and powerful, along with some SkyPanels.

“The lighting setups were pretty intricate,” he remembers. “The camera choice was also considered; obviously we wanted a camera with a good sensor so we wouldn’t have to overlight too much on scenes, because personally I don’t light scenes for the sake of having those lights on set. I light for the scene rather than the person, so it’s making sure that the environments feel right and then catering for the actors.”

Engaged approach

As Appeti and Okoli were both executive producers on Jungle, it meant being very hands-on with every department, including scouting. “We really wanted everything to have an iconic, powerful look to it,” Appeti recounts. “We were trying to find places that look beautiful and symmetrical – symmetry is a big thing with us when it comes to shots, and the tone and colours of stuff. We went through hundreds and hundreds of places, but we had to pick each location for its texture.”

The series was mostly shot on location in London but a handful of sets were built, including a living room for a scene in episode one where a character ends up getting shot. Using the Phantom, the team shot at 1,000 frames per second to capture the dramatic events in slow-motion. As the camera demanded more light, the DP wanted the whole of the ceiling to be able to be lit.

“We used frosted Perspex panels, then we blasted the light off a rig straight through the top of [the panels], so that the room was ridiculously bright. Compared to what you see on camera, it was probably 20 times as bright! So we had to make sure nothing was underexposed.”

Another interesting technical challenge was a music video-style scene in episode two, which sees three versions of Gogo getting in and out of a car. It turned out to be the longest shot they tackled in post, with Covert’s Simon Dewey leading.

“What we didn’t think about – and I’ll never do it again – was that as Gogo’s getting in and out of the car, the car would lower as he sits down and rise as he gets out, due to its suspension. So, when it came to matching the plates with the three Gogos, things weren’t aligning. It was a massive task for Simon to manipulate the frames and make it seem as seamless as possible. Next time we know to take the wheels off and put the car on bricks, so there’s no suspension.”

Appeti had prepared lots of references and colour boards to show colourist James Bamford to establish his desired look for the series, and he immediately understood their vision.

“Because I’m from a background of doing everything myself – the editing, grade, shooting – the grade and tone of it was really important,” says the DP. “I had a lot of references, colour boards and tones to show our colourist, James Bamford, and he really got it. It was a pleasure to sit in that room with him for three weeks, seeing your content come to life.”

A season two of Jungle is mooted, with a different music genre as the subject a possibility. But the Nothing Lost duo have another nine projects that are keeping them busy.

“Jungle was the easiest one to put out first because of our connections with artists and getting things done,” says Appeti. “The other stuff is nothing like Jungle and more traditional narrative-led stories. There’s also potentially an American version of Jungle…”

For the meantime, the pair are sated by the first series’ success. The DP continues: “Sometimes people think you’re saying stuff that’s too big for what you’re going to execute, but I think we weren’t far off what we said we were going to execute. It looks how we wanted it to, and part of the look is how it makes you feel and for us, feel was a really important thing.”