Gripping yarn

Bruno Delbonnel AFC ASC / Miss Peregrine’s Home For Peculiar Children

Gripping yarn

Bruno Delbonnel AFC ASC / Miss Peregrine’s Home For Peculiar Children

BY: Ron Prince

No one loves dark fantasy perhaps more than director Tim Burton, and his latest movie, entitled Miss Peregrine’s Home For Peculiar Children, is no exception. The production is based on the 2011 novel of the same name by Ransom Riggs, in which the spooky story was told through a combination of intense narrative and quirky photographs taken from the personal archives of collectors listed by the author.

The tale concerns 16-year-old Jacob Portman, who, after a horrific family tragedy, follows clues that take him to a crumbling orphanage on a Welsh island – “Miss Peregrine's Home For Peculiar Children" – run by the mysterious Miss Peregrine. He is selected to defend the Peculiar Children from a sinister band of monstrous forces that is hell-bent on slaying them.

From a script written by Jane Goldman, production began for two weeks in February 2015 in the Tampa Bay area, Florida, before relocating to the UK for location shoots near St Austell, Cornwall, and Blackpool Tower Circus, the studios at The Gillette Building in Hounslow, London, and finally to Antwerp in Belgium, where the orphanage exteriors were shot.

Lensing the movie was Bruno Delbonnel AFC ASC, Burton’s cinematographic collaborator on the comedy horror Dark Shadows (2012) and art-swindle biopic Big Eyes (2014). Delbonnel’s other credits include Le Fabuleux Destin d'Amélie Poulain (2001) and A Very Long Engagement (2004), both directed by Jean-Pierre Jeunet, Across the Universe (2007), Harry Potter And The Half-Blood Prince (2009) and The Coen Brothers’ Inside Llewyn Davis (2013).

Ron Prince caught up with Delbonnel over Skype as the cinematographer was taking a few days of rest and relaxation at home in Paris, prior to commencing prep on Joe Wright’s Darkest Hour, which looks at Winston Churchill’s charge against the Nazi army in the early days of World War II.

Was it an automatic ‘yes’ to work with Tim again?

BD: Yes, it was. I was on board from a very early stage, in fact. We were meant to shoot Miss Peregrine after we finished Dark Shadows, and before Big Eyes. We went scouting for a couple of weeks around the coasts of Wales and Scotland in search of an orphanage location, where much of the action takes place. But Tim acknowledged the script needed some rewrites, so Miss Peregrine got pushed back, and Big Eyes happened instead.

What research did you do for Miss Peregrine?

BD: Not a great deal. Ransom Riggs’s original book had a very poetic mood that I wanted to recreate on-set. It’s very visual, very unusual, about found vintage images, which are a bit weird – images where the flash might be too strong and you don’t see a face, or you just see a small part of a body. It was a great starting point for me to build the movie visually. The peculiar children are not superheroes, they are simply little kids with special gifts – one is lighter than air, one happens to be very strong. Peculiar, charming, gripping – all at the same time.

What were your initial discussions about the look of the movie?

DB: If you watch Tim’s movies, each of them is about people who are bit “different” or “peculiar” living in the “regular” world, facing regular people. That’s why the look of his films is always a bit twisted, but never totally gothic as people imagine. It’s always very simple and he really wanted to keep this sense of reality with a twist. You have to find a way to light “in-between”: scary and real at the same time.

On a more pragmatic approach, one tricky point of the story is a loop in time, where the action is variously set between two different periods – 1942 and 2016. Finding a visual way to help the audience place the story in the correct time period was a main talking point. In both the book and the script, the 2016 scenes, which are set in Wales, it is raining almost every day, whereas the action in 1942 takes place on just one sunny summer’s day, and we realised this was a way to make the difference – especially though the lighting. To take the idea a step further I shot some test material of the dinner sequence and then worked with Technicolor colourist Peter Doyle, who did the final DI, to apply a kind of 2-strip Technicolor look to the footage. We played around with various settings – the contrast and deep blacks to bring some strength to the image – and produced quite a strong initial look. Later in the final DI we dialled that look back to a more restrained level, in keeping with Tim’s request to ensure the images retained empathy with the characters.

What was the creative reasoning behind your choice of aspect ratio, cameras and lenses?

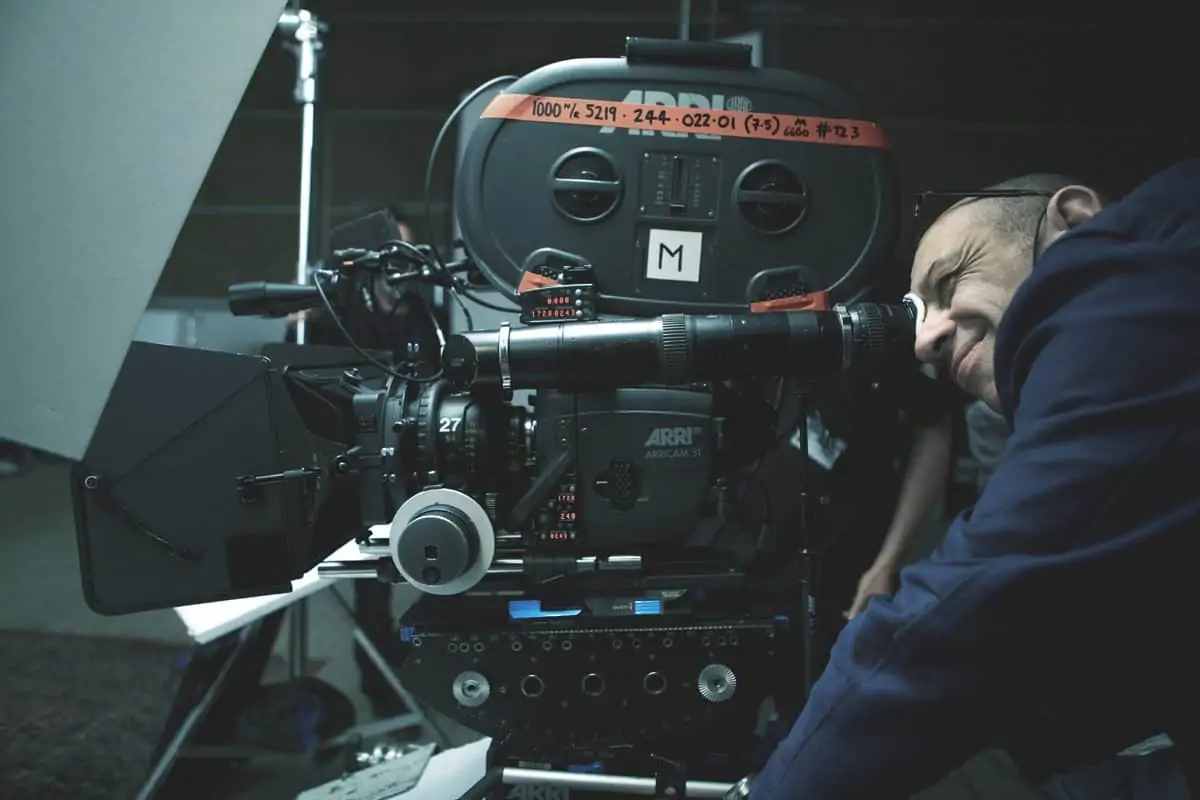

BD: I am not a great lover of Anamorphic framing – the 2.40:1 aspect ratio always seems a bit odd to me, and the lenses have ugly distortions that are just not to my taste. And 1.66:1 is not interesting. I prefer 1.85:1, as it’s great for locations and sets, and I knew it would be the perfect fit for the different sizes of the characters – some are tiny, whilst others are over 6ft tall. So 1.85:1 is a great compromise, not too tight, and not too wide. I went with Cooke S4s lenses. I selected the ARRI Alexa Studio as it has an optical viewfinder. I like to light with the finder, and don’t understand how you can light with an electronic finder in the camera nor a monitor on set. OK, the eyepiece on the Alexa Studio is a bit darker, perhaps 1.5 stops, but it’s great for my purposes. Panavision provided the camera and lenses.

Was Miss Peregrine always planned as a digital shoot?

BD: No, the original plan was to shoot Miss Peregrine on film. When the movie got postponed, we began prep on Big Eyes in Vancouver, and decided to shoot that on film. But Technicolor shut down their local lab, and the nearest facilities were in LA or Toronto. Tim likes watching dailies first thing in the morning, and the cost and logistics of supporting that with film just did not work out. So we discussed the matter and went digital. Big Eyes was my first digital feature and, if anything, this exercise proved a great training ground for Miss Peregrine.

Did you apply any LUTs and diffusion on-set?

BD: My thinking is that I never had a LUT when shooting on film, and I would not want one when shooting digitally. I started to eschew filters on Harry Potter. If you soften an image with diffusion in camera then you cannot go back. For me, it’s all about getting the best digital file I can get on-set, like a good neg, and then taking that into the DI suite, where you have very powerful, creative tools to adjust the image. I kept the workflow very simple, shooting with ARRIRAW to get a fat, rich digital negative. Other than shooting one stop down, with a tiny increase in contrast, I had a very pure image. No filtration, no LUTs. Technicolor provided us with rushes on hard-drives every morning, which we viewed on calibrated monitors.

"As the cinematographer, we have to create a world for each movie and each scene. The frame, the acting, the light are all connected. I like to find the sweet spot of a good frame and to capture what the director is doing with the actors. "

- Bruno Delbonnel AFC ASC

Who were your crew?

BD: I had the absolutely top people with me on Miss Peregrine. The fantastic Des Whelan was my A-camera operator, and Biggles was my exceptional gaffer. They variously recommended the other crew including Vince McGahon, who operated B-camera/Steadicam, Matt Windon as first AC, Peter Marsden the DIT and Dave Maund the key grip.

How did you move the camera?

BD: We had two cameras on the shoot – the A-camera that was always on the go, plus a Steadicam ready-to-go as required. We had all the tools – Technocranes, dollies and tracks – but I prefer not to move the camera so much, and definitely not for the sake of it. As the cinematographer, we have to create a world for each movie and each scene. The frame, the acting, the light are all connected. I like to find the sweet spot of a good frame and to capture what the director is doing with the actors. It’s much more interesting to let the actors move, to see their body language, and play between a wide and a close-up in one shot, rather than having the traditional set-ups for wide, mid and close-up.

What was the shooting schedule and working regime?

BD: I had a decent prep time of three months, and then we shot from 100 days, from February 24th and July 24th. The working hours were five-day weeks, partly due to the UK laws governing the children and also partly because Tim prefers this regime. It’s a nice regular way of working for the crew and the cast. Movie production is very demanding and people need to rest at weekends. Longer hours are painful, and potentially very dangerous. We need to be protected. Just so I could be prepared I might do some pre-lighting with Biggles on a Saturday morning, and then would perhaps enjoy a bit of Blackpool’s attractions. I remember a beautiful moment watching an elderly couple dancing together under the proscenium in the Blackpool Tower Ballroom. It was a shame that we could not shoot there, as it’s an extraordinary place. I tried fish and chips too.

What was your approach to the lighting?

BD: The key challenge was how much to bend and shape the light between the two time periods in the movie. In the pub scene in Cornwall, we had to legislate for both at the same time with two different lighting set-ups in same building, as the action switches between the two eras. Generally I went with diffused softlight and bounced light for the rainy 2016 scenes, keeping things balanced, static and appropriately dreary. For 1942, the lighting was much more energetic, with 20k Mole beams and 20k Fresnels punching-in sunlight. I also used moving lights in the form of Martin MAC Viper Profile high-output luminaires, that are used in rock and roll stage lighting. Working with Biggles, I moved the lights behind the actors – such as on walls and foliage – to bring a sense of the sun constantly moving and give strange feeling of life and liveliness in 1942, and highlight the distinction between 2016.

What was your level of involvement with the VFX?

BD: I worked with VFX supervisor, Frazer Churchill, mainly during prep on the visual effects storyboards and previs sequences, and tried to follow these as accurately as possible in production given the practicalities and physics of the locations. However, as the script was evolving and changing the whole time – with VFX scenes getting added, changed and cancelled – we often did know when the monsters would appear, although we had a good idea of their sizes and shapes. So, during production, the key thing was that I knew to anticipate and that we would often need to be quick on our feet. My main involvement in the VFX process was principally about making sure Frazer had accurate information about the placement direction and quality of light.

Were there any happy accidents?

BD: Yes, the British weather. We were absolutely fortunate that when we started shooting in Cornwall on a 2016 scene, and needed rain, we got rain. And when we need sun, on a 1942 scene, it was sunny. It was incredible to get the exact weather we wanted everyday.

Did this production challenge you in any particular way?

BD: Yes, shooting a feature film of this scale, or any scale, at The Gillette Building was a nightmare. It doesn’t have proper stages in any aspects: low ceilings, no grill, pillars in the middle of the space to support the leaking roofs. Because of these limitations there were many things I wanted to do but couldn’t.

As for the creative aspect, I used a technique, with the moving Viper lights, that I had not really explored before. Although the fans on these lights are pretty noisy, and they can disturb the sound recording, you can use them in really interesting ways, around the sets and around actors. The performers can hit the lights at different points, and fade in and out of the image. It was a very appropriate technique for this story, and it’s something I definitely want to develop in the future.