Hi, Ho Silver!

Boja Bazelli ASC / The Lone Ranger

Hi, Ho Silver!

Boja Bazelli ASC / The Lone Ranger

When we asked Bojan Bazelli ASC what he found most challenging about shooting the Disney/Bruckheimer The Lone Ranger reboot, he says flat out, “There wasn’t a single simple shot in the movie. Everything was challenging. Nor did we have a second unit. It’s a complex film, which goes hand-in-hand with the way we shot it.”

Along with Bazelli and director Gore Verbinski, the new masked-avenger fable taps the talents of actors Armie Hammer as The Lone Ranger and Johnny Depp as Tonto, the native American warrior. Co-stars include Helena Bonham Carter, Ruth Wilson, William Fichtner and Tom Wilkinson. They worked from a screenplay by Justin Haythe, Ted Elliott and Terry Rossio, writes Wyatt Moss-Wellington.

Verbinski collaborated previously with Bazelli on The Ring (2002), a high-earning horror flick, widely praised for its visual style. The call came in while the DP was still working on Rock Of Ages (2012). Verbinksi remembered their rewarding partnership and asked Bazelli if he was free to lens The Lone Ranger. From then on the two sent ideas to one another via text message until Bazelli returned to Los Angeles, when they could chat more freely.

“For The Lone Ranger, Bojan and I had lots of discussions early on about the style,” says Verbinski. “We got technical, but we also talked emotionally in terms of how something was ultimately supposed to look and feel. We talked a lot about honesty; it had to feel honest. We talked about loss and the deeper tone of the movie. And also, in telling the story from Tonto’s perspective, meant it came from a certain Native American underpinning. We discussed how to bring dust, dirt and authenticity to the cinematography. The vistas and the locations had to feel like they were talking to you in some way and communicating.”

During their initial discussions, the director and DP quickly decided they would have to use as much daylight as possible, rather than relying on the beauty of dawn and dusk. “The Days Of Heaven (DP Nestor Almendros, 1978) aesthetic wasn’t right for an action-adventure film like this one,” says Bazelli. “The Lone Ranger’s script walked a fascinating line between quirky comedy and more sombre considerations. It’s a film with some really good messages. It’s also rollicking good fun,” he says.

“We decided to face the camera southward to get very good light throughout the day. We did office hours, eight AM to six PM, to use all the light we had. It was Gore’s vision to get as many shots in camera as possible, using the natural environment without green screens. It was great, always asking how to get those shots; at times it was like being a kid in a candy store.”

After a delay in production whilst the budget was finalised, Bazelli shot the film over 150 days in locations across US southwest region, including Moab in Utah and the Cimarron Canyon State Park in New Mexico, as well as sites in Texas, Colorado, Arizona and California.

“The prep was really very fruitful – about ten weeks,” says Bazelli. “Gore and I took the movie into our hands. We knew if we didn’t decide everything in advance and make a really strong commitment to the way we wanted to shoot the movie, we wouldn’t get results, as we were on exteriors about 75 percent of the time.”

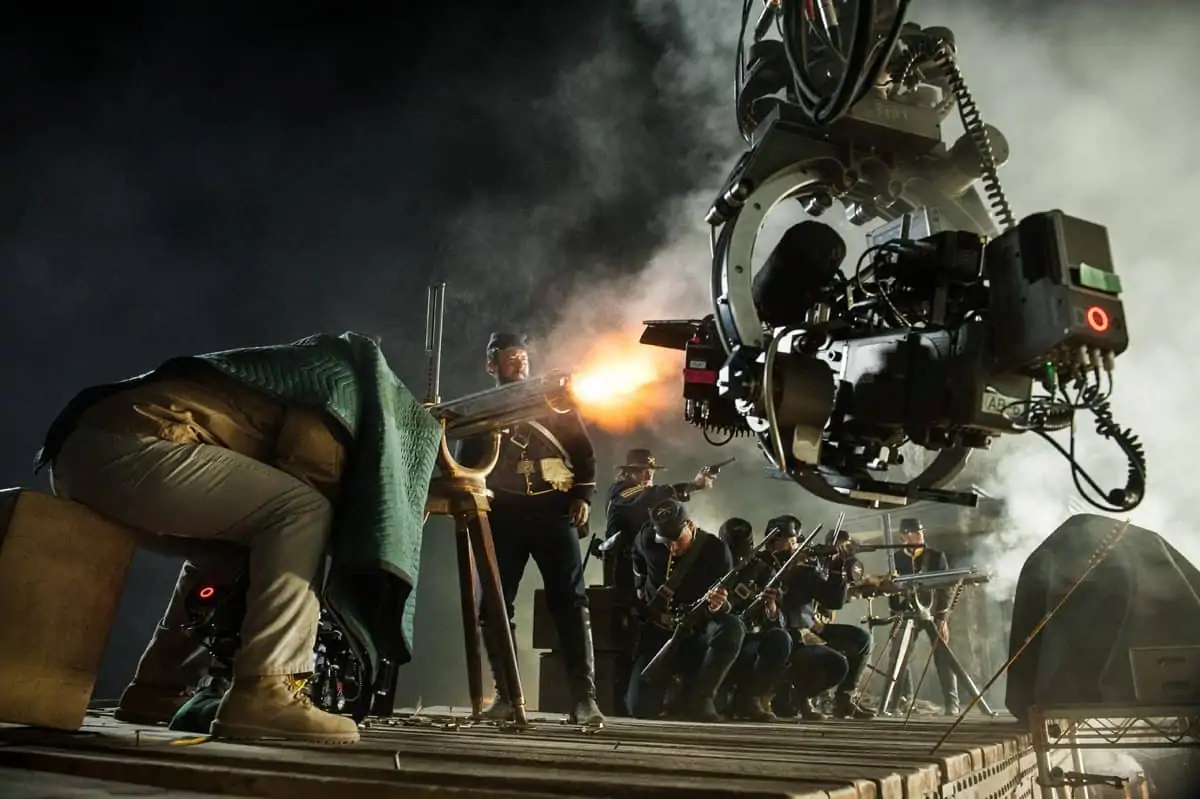

Verbinski’s method is to storyboard everything and pre-production was used to analyse the pre-viz, which, according to Bazelli, “made it much easier to discuss. There are two major sequences involving a train at the beginning and end of the movie; a chase sequence and a train crash sequence. Gore had generated the pre-viz about a year before pre-production even started. It’s the first bit of information I received when we started talking about the film – an eleven-minute sequence, from the trains leaving the station to the trains falling through the broken bridge and the underwater sequence. It’s jaw-dropping!”

They stuck close to the pre-viz, shooting with almost a dozen cameras to have flexibility with coverage.

He and Verbinski looked at references from John Ford’s The Searchers (DP Winton C. Hoch, 1956) to Sergio Leone westerns, but quickly decided – although the coverage and storytelling worked – the pallet was too chromatic for their purposes. They resolved to retain the framing and Monument Valley location visuals of Leone’s Once Upon A Time In The West (DP Tonino Delli Colli, 1968), however a closer chromatic reference is another recent reimagining of the modern western, Paul Thomas Anderson’s There Will Be Blood (DP Robert Elswit ASC, 2007). Bazelli and Verbinski resolved to work on a desaturated image, but wanted a different kind of approach to the otherworldly desaturation of their earlier innovations for The Ring.

The pair considered the use of filters and underexposures, however they didn’t want to have any more glass in front of them to complicate multiple camera exterior shoots. Fundamentally, they wanted to avoid destabilising their flexibility by putting the negative into the process and determined to achieve these results in print. They also planned early in their discussions to shoot on film, which complicates this kind of light capture further by retaining the silver in the negative.

“We had around seven film cameras, a combination of Panavision Panaflex Platinum and Arriflex 435s, plus four ARRI Alexas, shooting Anamorphic,” explains Bazelli. “One always on a crane; the rest were a mix of dollies and steadicam, etc. Most of the time we used vintage C-series lenses. Some from the ‘50s and ‘60s, some remakes, but the beautiful older glass wins the battle. They have an aged feel and the glass is not so perfect, so every time you point the camera into the sky or to a greyer background, they tend to softwash the foreground; they have bleed because the coating is not as faultless. That feeling of imperfection – but still very sharp – we embraced. They don’t take stronger light as easily as the newer lenses (like the G-series), and in our minds this was an advantage.

“We were lucky to get the older lenses working on such a massive project, but the Panavision connections helped. They’re all hand-maintained by Dan Sasaki, who basically adjusts the lenses and provides what you ask for. For example, if you want more flare, if you wanted them softer, if you want them super-milky, he basically works like a chef and cooks them up the way you want them to feel. They’re great at Panavision. They can do that.”

Bazelli used digital predominantly for night shoots, but the majority of The Lone Ranger was shot on film. “The daytime exteriors are big landscapes, always a film choice. Shooting Anamorphic made it the obvious option to go for the cameras that fit those lenses. But what’s beautiful about the digital world in my mind is the ability to get detail and subtle nuances in a relatively inexpensive way, with reasonably simple lighting set-ups. Knowing we’d be shooting night exteriors without heavy, strong, artificial-looking light, we wanted to avoid the certain exposure you needed for film. Night photography always feels a little stranger and we know it’s something we can’t surmount – obviously you can’t run Anamorphic lenses under a certain exposure or blemishes show up and you make a lot of compromises with focus and noise – so we needed to be very prepared with our lighting package and we did a lot of tests, consisting of multiple exposure adjustments.

“To prove the point about the look for night exteriors, during testing I ended up changing the exposure on film by lowering the frame rate from 24fps to 6fps, which equals about 1200ISO; it let me minimise the light. This would be our night look if we shot on ARRI Alexa, but documented on film because the camera was not yet available. I showed it to everyone – the lower light level looked beautiful and it was better than shooting spherical; I was keeping my eye on development of the Alexa with the full chip supporting Anamorphic lenses, which became available within the last three weeks of pre-production. We got it straight from the factory in Germany.”

Everyone expressed excitement about the way the night exteriors looked, especially Verbinski. All the equipment was supplied through Panavision, including the Arriflex cameras.

"We had around seven film cameras, a combination of Panavision Panaflex Platinum and Arriflex 435s, plus four ARRI Alexas, shooting Anamorphic."

- Bojan Bazelli ASC

While action sequences often employed the full range of cameras, dialogue sequences were predominantly shot on one camera: “Gore likes the lens very close to the actor, so the B camera doesn’t have anywhere to go to create a good matching cut. We don’t have the option of going wide and tight at the same time; one would suffer, usually the wide, so it’s easier for him to change the lens and go wider or tighter in two different scenarios.”

Martin Schaer operated the A camera and Rafael Sanchez gaffed. Mike Popovich was key grip and Jason Talbert the dolly grip, with color timing completed by Stefan Sonnenfeld at Company 3 in LA.

“We carried two cranes all the time,” says Bazelli, “a MovieBird 17 and a MovieBird 35/45. The grips often mounted them on platforms on the train so we could reach around to get the shots. It was amazing to watch Jason, our dolly grip, nail camera moves with great precision while the train travelled at speed, or while we were hurtling down winding canyon roads at 45mph on our road rig, which we made by mounting the train and our Condor ‘smokestack’ on a 150-foot-long flatbed pulled by a tractor-trailer. We used the road rig when we were in locations with no track, or when we needed to go faster than 30mph.”

One problem the crew encountered centred on keeping the vintage lenses free from the rig-ravaging elements. “We were embattled by all sorts of weather: extreme wind, sandstorms. In New Mexico around April, the wind season starts with crazy temperature changes. In 15 minutes a beautiful day would just turn into wind and sand in your face with masks and goggles being needed. In Utah and Arizona it was extreme heat in the daytime, then cold in other areas for night shoots, and we shot below freezing at ten thousand feet, but the winds in New Mexico were the worst!

“It’s hard on the crew, but even harder on the equipment. We had to replace some of our vintage lenses because the sand would get inside them. We were shooting on film too, with complicated set-ups – on top of trains, with cranes and all manner of moving parts!”

The crew relied on one film stock, also new on the market: Kodak’s 5203, 50 ISO daylight stock, which replaces the old 5201. Bazelli describes it as, “a beautiful fine grain and a clean, natural look, which responds beautifully to highlights. The blacks are fantastic too. It’s a stretch for digital to get to this.

“I ended up pull processing [under-developing] the negative in the end, so everything looked a little softer, a little less saturated, extending the usable range of the film. When combined with a hard print, 30% bleach bypass, it blends a bit better, making a nice combo. We had about a million feet of film, about 500,000ft in digital – it was all developed with pull one stop, effectively making the ISO 25.”

Shooting a lower speed film stock aided in the objective to keep a naked lens. They kept everything, including the workflow, as simple as possible: film cameras without cables, no unnecessary connection to DI personnel advising on the digital image – as rudimentary, punchy and fast-moving as possible. “The ideal is just you, your meter, the camera and magazine,” says Bazelli.

Watch out for his favourite scene right at the beginning of the film: the scholar-cum-vigilante sits on a train, with buffalo reflected in the window, romantically establishing the old west. A shadow catches his eye, setting up the drama of an inciting murder to come. The theatrically satisfying moment was achieved by adding cracks into the ceiling of the train, achieving some flare with the lighting and planting light outside, to create the effect of looking into the sun. The romance and the adventure of the New Western are literally reflected in the scene.

Says Bazelli, “You know, I don’t think we’re ever going to return here again: this scope and this size, using as much natural environment and light as possible, minimising the green screens… it’s a rare production that is willing to make such a commitment these days. Everyone on the crew worked very hard to achieve this and I’m so lucky I could be a part of it.”