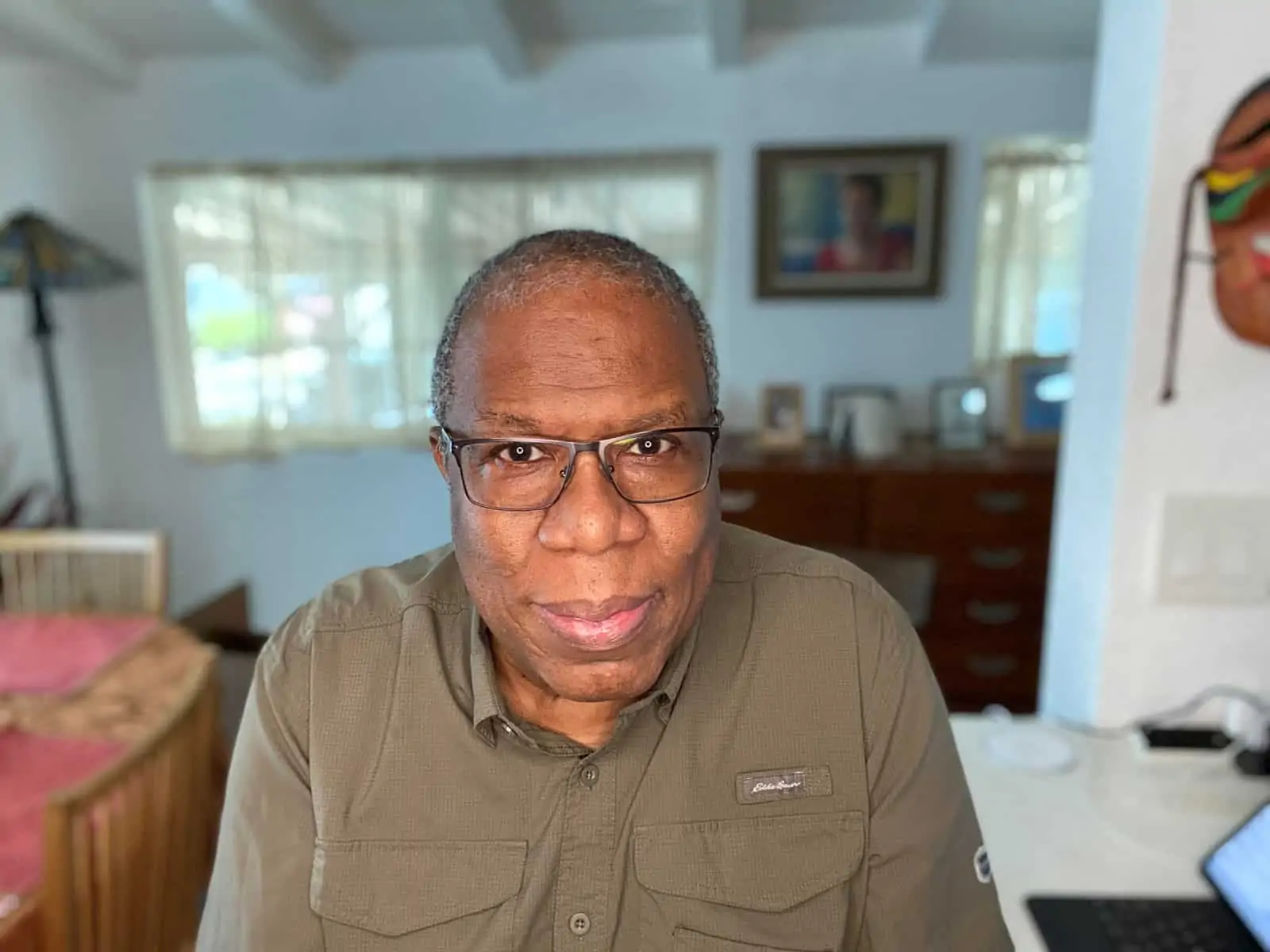

Karen Pyudik talks to Bill Dill ASC about teaching cinematography and inspiring and empowering the filmmakers of the future as they overcome creative barriers and develop individual relationships to filmmaking.

Bill Dill ASC continues to empower the new generation of young filmmakers. He can reach them, where other teachers fail to understand a significant shift towards individual filmmaking. Dill understands the impact technological changes have on his students which leads to a measure of freedom to create and distribute diverse cultural expressions. His list of students includes Rachel Morrison ASC, Melina Matsoukas, Jonathan Sela, Diego Quemada-Diez, Oscar Duran, Tassaduq Hussain, Tabbert Filler, Terrance Hayes, David Waldman, Masanobu Takayanagi, Stephanie Marin, and many more.

A graduate of Oberlin College with a Bachelor of Arts degree in Communications Studies, Dill is currently a Full Professor and Head of Cinematography at Chapman University in Orange, CA. He is also a past Department Chair in the Cinematography Department in the AFI Conservatory at the American Film Institute and Senior Filmmaker in Residence in that department. Dill taught at KAFA, The Korean Academy of Film Arts in Seoul, Korea – the school that Parasite director Bong Joon-ho attended. In 2002, of the eight commendations awarded by the American Society of Cinematography for excellence in student cinematography, four were granted to students of the program over which Dill presides.

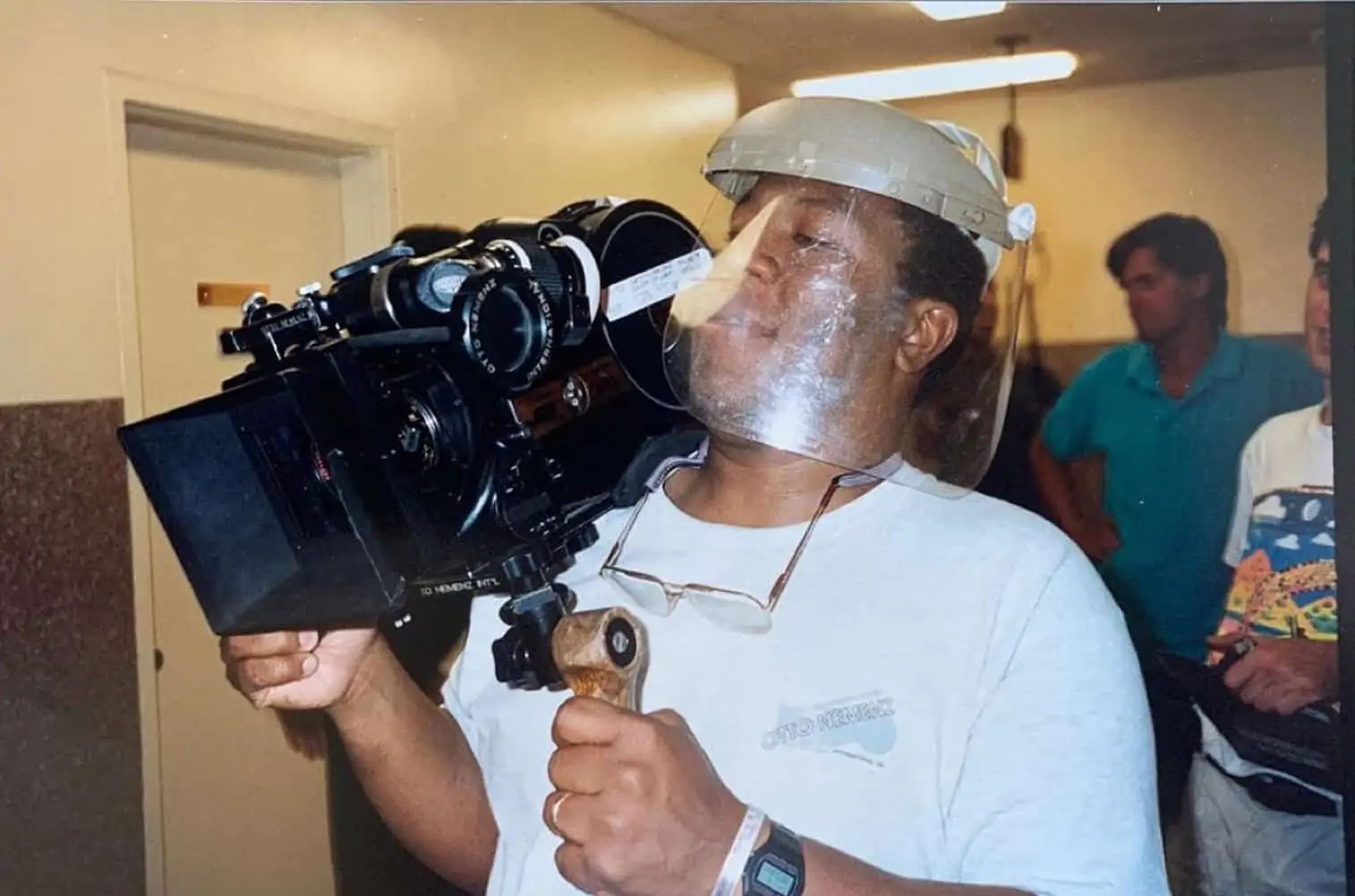

He has guest lectured at The University of South Carolina, The University of California in Los Angeles, Los Angeles Community College as well as lecturing before senior members of the United States intelligence community at the Institute for Creative Technologies. Dill has worked closely with the Entertainment Technology Center at the University of Southern California and was the cinematographer on the “Studio Without Walls” demonstration of future broadband technologies. In addition he lensed Sidewalk Stories (which won the audience prize at the Cannes Film Festival and the Silver Bear at the Berlin Film Festival), and worked with Robert Townsend on The Five Heartbeats.

Dill is an active and respected member of the Los Angeles filmmaking community, having worked in all facets of cinematography: corporate films, documentaries, TV pilots, episodic TV, commercials, movies of the week, and feature films. He has participated in numerous panel discussions on the cinematographer’s role in modern filmmaking sponsored by such organisations as Showbiz Expo, and the American Society of Cinematographers. He is also a regular mentor and teacher of minority youth community groups such as the Hollywood Entertainment Museum’s Education Center for the Entertainment Arts.

You brought up generations of incredible cinematographers/visual artists. How do you see the difference between the generation of baby boomers, GenX and Millennials? What are the different ways we approach storytelling?

First and foremost, above all else, I do my best not to think of my students in groups. I think it’s incredibly important that you look at every single student as a “one-off”. Yes, I understand that there is some value in studying the characteristics of GenX and Gen Z. I’ve listened to lectures by sociologists and psychologists, talking about each generation’s tendencies. I do understand the technological changes and the impact the technological changes have had on young filmmakers and young people in general. I understand that. I am a father of two young creative people. I understand the impact the world has on them and how fundamentally different it was for me. It was something to go to college and not have a telephone. You can’t pick up a device and see your parents or see your friends.

On the other hand, I have to work in a particular way. I have to look at every single individual, cinematographer, filmmaker, and figure out what’s keeping them from doing their best work. That’s how I started. I always assume that something impedes their growth. I don’t spend a lot of time thinking about that or worrying about that. I just sort of take it for granted. It’s important to me, that I have to look at each person. I have to listen hard to that person. I ask a series of questions in the first class every year. I’ve been asking these questions since 1993 when I started full time as a teacher. ‘How many of you have seen more films in a movie theatre than you’ve seen at home? Secondly, ‘How many Academy Awards-nominated films have you seen? Have you seen all of the Academy Awards-winning films?’ I ask.

In 1994, I started asking these questions and tracking the change. There are several things embedded in that. Do they have an institutional sense of filmmaking? Academy Awards? How personal is their relationship with filmmaking?

When I started teaching, my students would look at me like I’d just insulted them. It was kind of an absurd silly series of questions. They were like, ‘Look, we’re film geeks. That’s our canon. Academy Award-winning films are our exemplars.’

Now, when I ask how many of you’ve seen Academy Awards-nominated films, only a few hands go up. ‘How many of you saw Academy Award-winning films from last year?’ I continue. A few more hands go up. But not the majority anymore. ‘How many of you’ve seen films in a movie theatre rather than at home in all of the forms you watch movies: iPad, iPhone, on your computer, on a 4K TV?’ I ask. A smatter of the hands goes up.

Is there a difference between your foreign students and your American students?

No. All across-the-board. Societally it tells me that the gatekeepers are dead. The people who once owned our filmmaking aesthetics are no longer due. The Academy Awards are less and less culturally relevant to my students.

Do you have a theory on why Academy Awards seem extraneous to the new generations?

Because everyone has their own culture. Having a common filmmaking culture, that is no longer the case. Of course, we have friends, and we have colleagues, and we have cohorts that we move through the business with. Still, I am telling you, each student has an individual relationship to filmmaking, which is in that sense fundamentally different from what the relationship students used to have. It used to be institutional. It isn’t anymore. It’s individual (and so are my students’ aesthetics).

When I started teaching, it was all film. Then I was able to move pretty seamlessly from film to digital because it wasn’t about the mechanics. It was never about the mechanics. I can still go through the lecture that I used to do about processing film if you want to. I can take you through every step of the construction of the film emulsion and the impact that it has on the look and the feeling of the image. And I can do the same thing when I am talking about Sony Venice (6K). I can do the same thing now when I am talking about DaVinci Resolve.

The reality is that it’s always been about overcoming that individual student’s creative barriers. Whatever is in their way, whatever makes them make decisions that are not the best for the story, getting those out of the way. I am giving a greater level of understanding of underlying fundamentals. Those things have not changed for a millennium, or two or three. Storytelling is sitting around a campfire and you hear someone spinning an amazing yarn. I doubt fundamentally if that’s going to change or has to. But the pace has changed. No question about it.

The weight at we which we absorb imagery is faster than ever before. Just look at the length of a shot, the mechanics. The shot length of The Wizard of Oz doesn’t hold up very well today, when you look at it. But the underlying human experience of it all is mechanics too, shot rate. Fury Road is a good example. Look at the length of a shot. You couldn’t do it fifty years ago.

What’s your teaching philosophy?

There are four fundamental questions cinematographers must have the answer to before they start shooting the movie.

1. What’s the story (not the plot)? Tell me the conclusion you’ve drawn in constructing this movie.

2. Who’s story is it? Directors usually say, ‘it’s everybody’s story.’ But whose story are you telling? I am trying to get these kids to be clear about priorities. This is the narrative point-of-view. Here’s the person whose story we’re telling.

3. What is it the characters want? I am not talking about what plot has them trying to acquire. From that character’s point-of-view, you show what they want and how bad they want it. Then you show the thing that’s stopping them. The thing that they’re after is just a “stand-in” for something bigger, something deeper, something more important. In every story, the character is trying to achieve something. He is trying to get something. He is trying to acquire something. One of the basic questions I ask ‘So if they achieve that, everything is fine, right?’ Seldom everything is fine just because they got the thing the plot says they’re after. But we photograph things to act as a “stand-in” for the things that we can’t photograph. We have to personify things. It can’t be just a guy. It cannot be just a woman. Otherwise, you don’t have a movie.

4. How come they can’t have it, that thing that they want? What’s up with them? Why can’t they just go get it? That’s where the majority of the movies fall apart. You might say, the problem was within the characters themselves. Obviously. However, you can’t photograph problems within the characters themselves. There has to be something, some external force, something we can photograph, which is once again “stand-in” for something that’s keeping the characters from getting what they want. We need to know how to photograph symbolic things. You don’t know anything until you know those four things. Then you can get your HMIs and LED lights.

I think it’s nonsense when a cinematographer says, ‘I have a style and I am just going to apply this style to every movie I photograph.’ Look at Storaro’s films. Look at how different they are: Little Buddha, Apocalypse Now, Reds, Dick Tracy, The Last Emperor. Show me the style? People say it’s in his exotic use of colour, in fact, very precise use of colour. I worked with his gaffer and paid a lot of attention to how Vittorio works. The tools are pretty much the same. However, look at how different his films are. Reds is almost a documentary. Little Buddha is stylised. Dick Tracy is a graphic novel. That’s quality work to me. Storaro has incorporated the stories so powerfully, so effectively and on such a deep level, that the expression “my style” seems kind of trivial by comparison.

Do you teach by example? Do you show students a lot of films?

I show huge hard drives full of what I consider to be really fine examples of work. They’re just examples of solving that problem, overcoming this situation. Or on the flip side, the examples of not doing very well at all. You can learn from work that doesn’t work as well.

I show classics like Howard Hawks’ Bringing Up Baby (1938), Fritz Lang’s M (1931), Orson Welles’ The Magnificent Ambersons (1942), Charles Laughton’s The Night of the Hunter (1955) Cinematography by Stanley Cortez, who is a hero of mine.

I also show contemporary films like Atomic Blonde and John Wick. There are some amazing images in these films. Jonathan Sela is a student of mine. He is a very talented cinematographer. I use Rachel Morrison’s work. I like to show Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead, Little Children. I like to keep it as wide-ranging, as big a palette of possibilities as possible. I show Belgian mockumentary Man Bites Dog. It’s a brilliant film. I saw it at Sundance and immediately incorporated it into my teachings. It’s so wonderful to talk about the filmmaker’s involvement in making the film and the audience’s involvement in what’s on-screen. The audience is looking at the filmmaker. The filmmaker is looking at the audience.

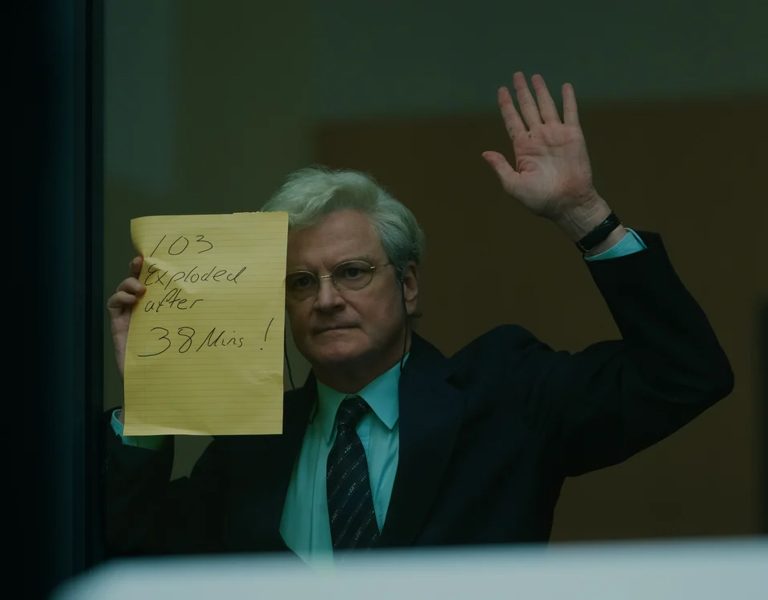

In my class, I use a scene from Magnolia to talk about extreme racism in filmmaking. It’s just extraordinary how racist that film is. There is a scene with the character named Marcie. It is one of the most racist scenes I’ve ever seen on-screen. It had a lot to do with police brutality and racist bias. Paul Thomas Anderson justifies a white police officer walking into a woman’s house and pointing a gun at her. It’s supposed to be funny. I am talking about camera movements. The way camera movement is used to convey a character. We create contrasts in movies. The camera movement helps to create a contrast between Marcie and Officer Jim Kurring (John C Reilly), who comes to her home. So we have to contrast Claudia against Macrie and the way we do that is with John C. Reilly’s character, a police officer in that movie. It’s a profoundly racist series of scenes in Magnolia. I want them to recognize racism. It’s as racist as The Birth Of A Nation. It’s horrifying. A police officer handcuffs a woman to her sofa and they make it OK. It’s a comedy. It’s comedic.

You’re teaching millennials and the Z generation. Do they see racism in these scenes? Are they aware of systemic racism?

You would think that. No. They just laugh. They think it’s funny.

Do they think that racial inequality is no longer an issue?

It’s amazing. I’ve shown that scene many times. I’ve not seen a single student saying, “My God! That’s horrible!” Then I show it to my students from my perspective.

Bill wrote a piece called “My Comments on The Birth Of A Nation Posters”. It’s an essay about celebrating the controversial “The Birth of A Nation” as a classic by hanging its posters in the hallway of Chapman University Dodge College. He writes: “I would strongly encourage that is a part of this debate we screen Birth of A Nation in the Folino Theater. At the end of that screening, I would like anyone who supports the continued display of those posters to look into the faces of those students who have reacted to the presence of those posters and say to them, “I think you should be reminded of these images every time you walk through the hallways of Dodge College.” To quote Justice Louis Brandeis, “Publicity is justly commended as a remedy for social and industrial diseases. Sunlight is said to be the best of disinfectants; electric light the most efficient policeman.” The most effective way to destroy putrid ideas is to display them and then discuss them.”

How do you teach your students to express daring ideas?

My students are focused on penetrating deeply into the marrow of the narrative and finding a visual language that is unique to their story and their perception of it. They need to recognise that their perception of it matters.

My students are developing the courage to unflinchingly look at the reality of the story. They often hide from the pain of the story and the reality of the story. I call it “flinching”. It’s like a nervous movement as a reaction to fear or pain.

It’s so much easier to get lost in the technical details. How many photosites (light collectors)? How many Ks? You still gotta do that. It’s like chords and scales. It’s a given that you need to have absolute command over depth of field and circle of confusion. I used to require my students to do the depth of field calculations without the depth of field calculator. They just needed to learn the formula.

I relentlessly try to make them look at the reality of the story. I spend most of my time trying to teach people how to see. I ask them ‘Did you look at the light? Or did you look at symbols for light: the key light, the fill light, and the backlight?’ That’s a symbol for lighting. That’s not lighting. I am trying to get them to look at the real thing, not a symbol for the thing and not an artificial representation of it. I ask them to look at happiness, loneliness, redemption, captivity, and freedom.

Which innovations do you recommend to your students?

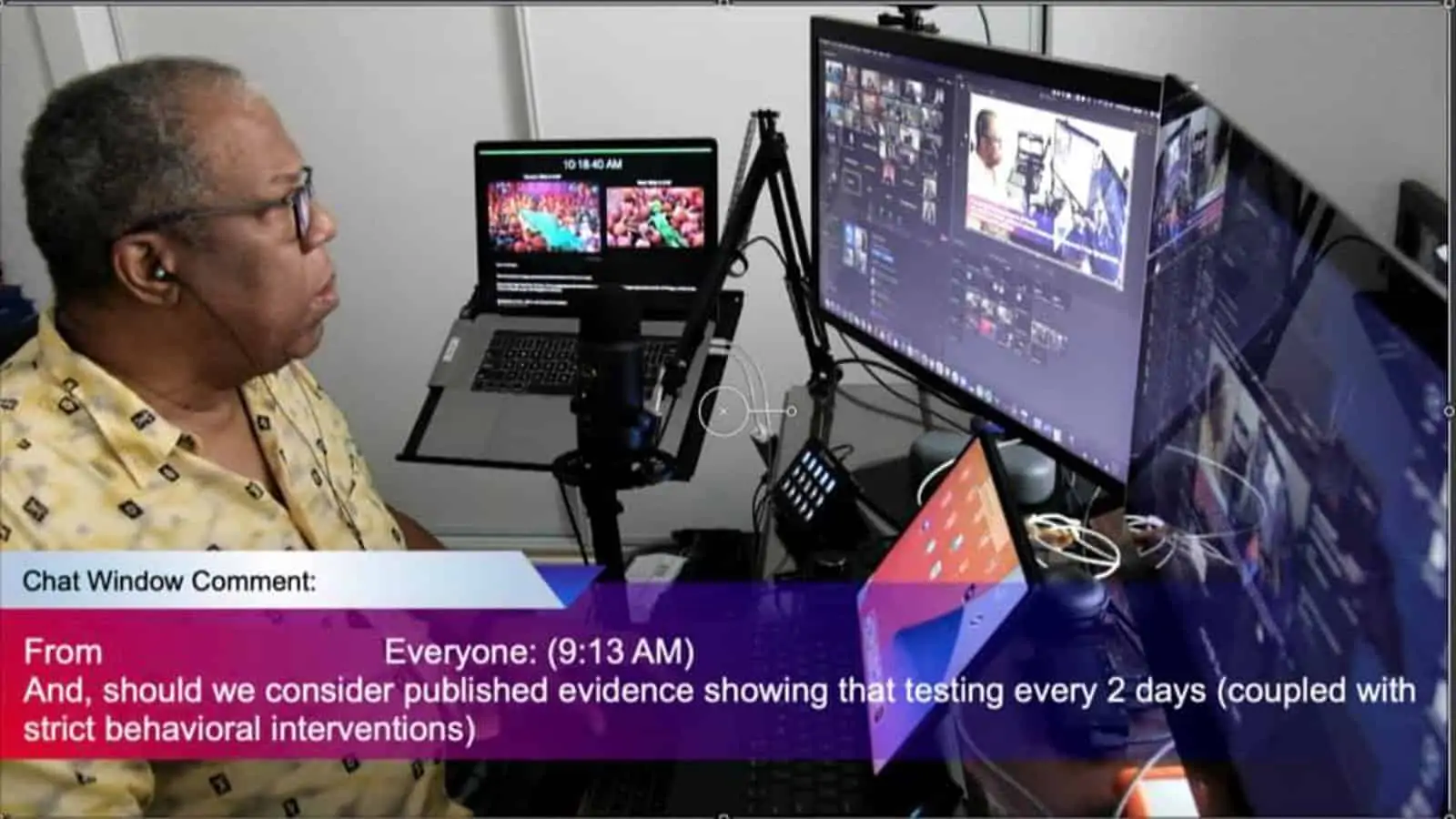

The one innovation I’ve recently seen that’s impressed me the most is the Sony Venice camera. My wife and I shot a short film with it during the COVID lockdown in LA. I colour graded the film in Davinci Resolve. I loved how seemingly effortless that camera made the work. We shot night exteriors looking into the sky and could pick up clouds in the night sky. The look was so lovely, delicate.

The ability to remove the lens and sensor from the camera body is a compelling feature. It allows the

cinematographer to create images from perspectives that would otherwise be impossible, and it does this with full quality. The Sony Venice is quite a beautiful camera.

BY: Karen Pyudik