PREHISTORIC PERFECTION

Directors Adam Valdez and Andy Jones spoke to British Cinematographer about their collaboration with MPC when delivering the mind-blowing VFX of Prehistoric Planet.

Apple TV+’s latest adventure into the natural world, executive produced by VFX veteran Jon Favreau and narrated by David Attenborough, is awe-inspiring in its attention to detail. The series is a beautiful balance of real footage and an incredible array of VFX mastery, backed up scientifically by the latest discoveries of our prehistoric world.

Divided into five episodes, each comprising of a different dinosaur locale from coasts to forests, directors Valdez and Jones were determined to achieve a documentary-style feel.

How did you collaborate with cinematographers when constructing the models and prehistoric worlds?

Adam Valdez: As directors for this project, we had some unique challenges in that we had to carefully previsualise all the sequences in animation before filming anything. Part of that process was getting very specific with camera style, mimicking how documentary footage of large & dangerous animals is achieved. Once we had figured out the dramatisation and camera coverage and settled on an edit with BBC Natural History editors, we had our shopping list of background images to get in the field. Of course, reality gets in the mix, and our field cinematographers brought all their skills to the party, providing the gorgeous imagery these planet series are known for.

Andy Jones: I have to say it was truly a dream to work alongside some of the best Natural history cinematographers in the business. There were several, but Paul Stewart – wow! The man has shot some of the most memorable natural history scenes in the past two decades. He has such a sharp eye and a keen sense of realism in composition, performance, and light. His notes were so detailed and spot on. Our entire team at BBC was exceptional. Great storytellers and collaborators. It was intriguing to learn how they work.

What existing creative inspirations did you draw from?

AV: I’ve been a fan of nature documentaries and science programming my whole life. It was very fulfilling to meet some of the masters and collaborate. There is a cadence to these films, often shot at high speed and with graceful cameras, which is infectious to watch, and I tried to capture that same feeling. Also, I always tried to feel like I was about to capture an unlikely or lucky moment so that throughout the cuts and camera work, it would feel like we were watching an assembly of footage that was barely achieved in the field.

AJ: I would say that most of what BBC NHU has done in the past 20 years. Most of which was overseen by Mike Gunton, our EP. Jon Favreau and I always said that we were using BBC NHU docs as our inspiration for The Jungle Book and The Lion King. We strove to make our shots as real and beautiful as those nature docs.

How do you ensure that the models you create are as scientifically accurate as you can? Does this add more pressure?

AV: There was a constant over-the-shoulder presence between all the scientific advisors, so I didn’t feel it as pressure as much as incredible specificity that brought nothing but more interest to the task. We only had debates about drama versus fact, which were always interesting. Sometimes, a scene needed dialling back to be more realistic and genuine, and we found more novel ways to be entertaining and engaging.

AJ: We worked with Dr. Darren Naish – A world-renowned palaeontologist. His insight and guidance were vital to us reaching the highest level of accuracy and detail with the latest research in the field. There is much pressure to get it right. The scientific community can be quite loud. If you don’t have them on your side, the project will fall flat. With Darren and his team of scientists’ insight, we knew we were getting as close as possible to what these animals were really like. Of course, some design elements were up for grabs, as they had no fundamental research to define them one way or the other. In those cases, we would rely on our artistry and expertise of having done realistic CG animals for the past seven years.

What effect did Hans Zimmer’s score have when doing the VFX work? Did you use it as a reference point at all?

AV: We had various temp scores throughout the development of each scene and the writer/producer of each episode selected that for tone. It always helps to understand beat by beat and what kind of shape a sequence needs to be.

AJ: Hans has worked with the BBC Natural History Unit on several occasions. So it was a shorthand when it came to scoring each episode. We often worked with a temp track that was usually a piece of Hans’s from Planet Earth. I think they upped their game when I first heard what Hans’s team Bleeding Fingers had created for us.

A documentary style depth of field is used to add authenticity and realism to the show. How do you design the VFX to be viewed this way?

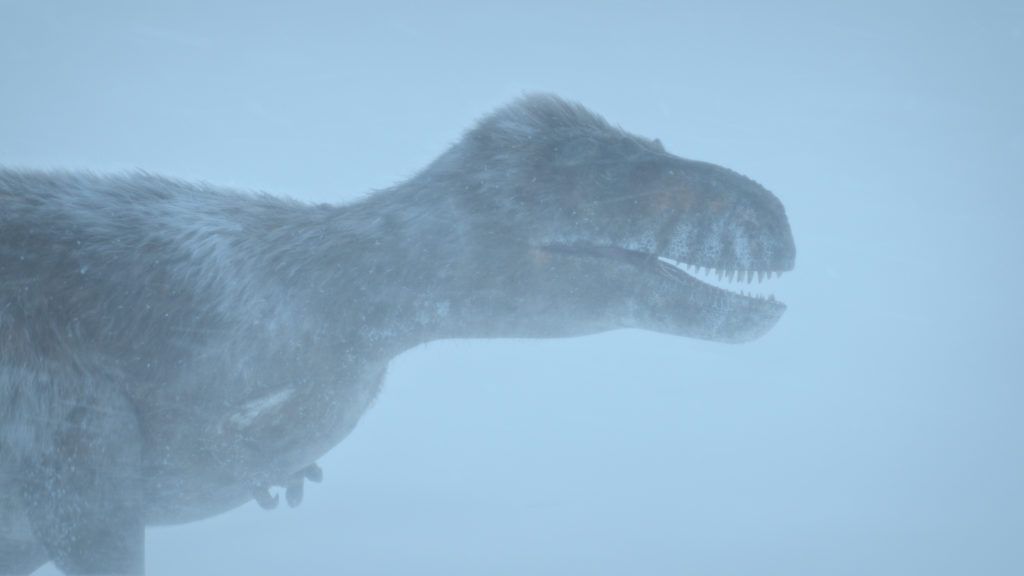

AV: While making the previs animation, we got very specific about lens choice, camera support, and more elaborate movements. So, while mocking up a camera in the computer to previs, I would choose sticks and a long lens as a base setup for most scenes. I would imagine that I’m out in the field hidden somewhere, filming this big predator way off, and I will get extended footage of eyes, teeth, feet, etc. Then perhaps do some drone shots orbiting high above. For Ice Worlds, I did some shots as if off of a snowmobile. So, it was always about imagining the real coverage. Depth of field was also accurate to the chosen lens. This way, when the actual background photography was happening, we had a specific guide on how to re-create the intention.

AJ: We designed every sequence to feel like it was shot with the same lensing and distance to subject that you get from a real wildlife documentary. We created a set of rules that would help dictate the look. For instance, if we were shooting a predation sequence, we limited ourselves in terms of distance to a predator. So a lot of long lenses and shooting as if we were hiding in blinds to get the pieces we need to put the story together. And then, if we were featuring a herbivore, we could get closer to them and could use more short lenses and even additional camera moves to help tell the story.

How much (if any) of the landscape footage is real? How often is it a blend of both worlds?

AV: Most of the time, the world is real. As usual, where animated creatures interact with their environment, we often have to replace portions or weave in things like grass and dead leaves that their feet kick through. Once you’re underwater, you look at many synthetic worlds made on the computer.

AJ: I agree. The underwater scenes are all full CG. To integrate our CG animals with the background, we often have to build some of the terrains they are walking on. This is the only way to shadow the terrain properly and even interact with the plants, mud, and snow.

How do you go about blending these intricate models with real life locations? How different is it to using virtual landscapes?

AV: Visual effects for all live-action projects combine to recreate the three-dimensional world inside the computer so that prospective matches between the computer subject and the real location. Often there are hand-made masks and other layering tricks to blend the images. And then a painstaking process of matching lighting and colour, so it all feels like one photograph. It takes many specialists similar to teams in live-action. When you blend a computer character into a computer background, everything is naturally already one item; however, now you have the challenge of trying to recreate an entire world in a photorealistic or appealing way! So, there are trade-offs.

AJ: Agreed! You have to pick your poison. There are many advantages to rendering a fully CG environment. Getting all of your shadow interaction and matting into the plate for free, just to name two. However, when you shoot a real plate, you get all the natural world detail of plants, rocks, dirt, water, and even wind in the trees for free. The difficulty comes when you have to integrate your character into that plate. Properly casting shadows on the complex real-world surfaces like plants and grasses is extremely difficult. And then adding footprints in mud and snow can prove very challenging.

What was the most challenging animal, or specific animal detail to construct?

AV: Feathers and hair in computer graphics are really complex. But actually, these animals have very thin skin that reveals anatomy underneath, and if that is not behaving organically, you don’t believe it. So I would say the VFX team had their work cut out recreating so many species of dinosaur anatomy.

AJ: All of them had their challenges. But the giant sauropods were some of our most challenging — the current findings of hollow bones that allowed them to grow to such massive proportions. I remember first seeing the wide necks from Darren Naish and thinking this must be a mistake. How could the necks be so thick? But science doesn’t lie. The size of the bones and the layout of the muscles dictate this shape. As animators, we have to justify the physics and movement of these creatures. The rigging team had their hands full, trying to rig the muscle movement and skin sliding on these massive creatures. Darren would tell us that the skin was not as loose as elephant skin, so we had to tighten it up – more like a Komodo Dragon.

As stories are being told, akin to the real-life footage of Planet Earth, does this change how you animate the creatures? For example, do you make them more emotive?

AV: We were cautious with implying emotions. Many dinosaurs had very small brains, and we all know now that modern birds are from the same lineage. So, for example, a mother and calf sequence is very different for dinosaurs than today’s mammals. All of that said, clearly, these were living things with tricky lives who struggled to survive. That is universal, and they wouldn’t have been such successful life forms for so many millions of years if they didn’t have some mental life and thoughtfulness of a kind. You don’t have to do much for humans, as such emotionally driven creatures, to project emotions onto animals of any kind.

AJ: We crafted the stories to feel familiar so that we could relate to these animals. They have been extinct for so long, and some of them are so alien-looking to us. We defiantly wanted our audience to feel a connection to these animals. We steered clear of anthropomorphising the animals, and we wanted to convey the feeling that you are watching the real thing. In terms of finding similar behaviour in today’s wildlife, we stayed away from mammals, as these prehistoric creatures were far from mammals. So we looked more at modern birds and reptiles. Birds do care for their young, but there is a lot less cuddling going on; it is almost instinctual and matter of fact compared to mammals. So we took that approach, and when we needed a bit more emotion to help a story along, we used camera lensing and cutting patterns to get us there, much like you would in a real documentary.

How much was created from scratch, or could you use some pre-existing models?

AV: Everything was created specifically for this project.

AJ: Correct. Every animal was built from scratch. Even if MPC had some existing models, they would not have been correct with the latest scientific findings. We had to make them all to spec with Darren Naish and his team of experts giving feedback throughout the entire process. There are so many minute details in these models, many of which are never even seen like the palatal structures inside the mouths and the teeth and gum layout.

These close-ups are often breath-taking in detail. Could you expand on the process of crafting the show-stopping shots of the series?

AV: Closeups allow the computer rendering to reveal all the loving crafts which went into these animals. There are artists at MPC who spend their working lives faithfully studying the details of all kinds of animals and objects to represent life’s complexity. You have to build all that detail so that it feels life-like even when you pull the camera back. We knew from the beginning that killer close-ups were part of what natural history documentaries are all about, so it was planned for.

AJ: I think the close-ups are our money shots. When I think of the strengths of the VFX artists at MPC, I think of the close-up creature work. From the model and texture detail to the subtle and bone-accurate facial animation rig to the gorgeous render and composing work to make these close-ups looks incredibly photographic. Working with these artists for over seven years on The Jungle Book, then The Lion King, and now Prehistoric Planet, they have really perfected the art of the close-up.

What models and sequences are you particularly proud of?

AV: Of the sequences I directed, I particularly like how two flying-reptile sequences panned out. The first involves babies in the flight of their young lives to cross a bay to safety on land, and the second is about ‘sneaky males’ on high-cliff mating grounds. Somehow the action of flight mixed with these dramatic settings and the way the edits came together just felt both truthful and exciting.

AJ: I have to say I love seeing dinosaurs in the snow. Adam directed the Ice Worlds episode, but I was able to shoot a few of those sequences while I was living in Switzerland during COVID. Several beautiful locations are right near my family’s home in Nidwalden. I knew those sequences were going to be something special, and I am very proud of the team at MPC for pulling off some very difficult integration and delivering one hell of an episode.

What can MPC’s work on Prehistoric Planet demonstrate about the future of VFX and storytelling?

AV: I think this project shows that there are many ways projects can start and many processes that can result in something that has its own life. Visual effects and computer graphics don’t imply a prescribed outcome. And MPC has done a great job innovating new ways of working and new technologies for collaboration. It also has to be said that teams of dedicated artists and filmmakers putting in very hard work is ultimately what realises the full potential of the piece, and that’s universal for any endeavour of visual storytelling.

AJ: With all the fantastic creature work and attention to detail from MPC, I believe the sky is the limit for storytelling. Budgets are still an issue; however, as real-time render technology becomes more the norm, shows like this will become cheaper to produce. This opens the door for filmmakers to stretch their imagination and bring amazing stories to the screen.