STAYING POWER

With over 90 credits to his name, Anthony Richmond has cemented his status as one of the industry’s iconic characters on both sides of the Atlantic. The cinematographer recalls his favourite moments from his decades-long career and the characters he met along the way.

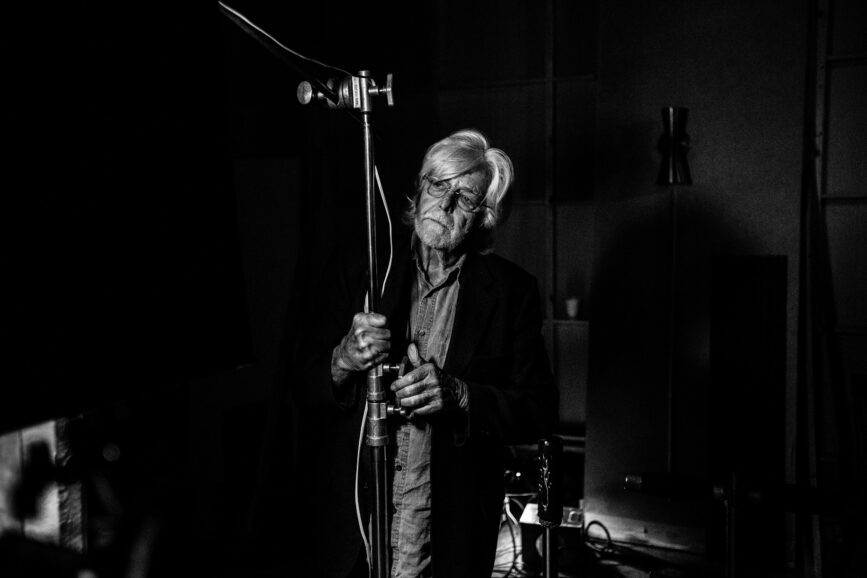

He’s worked with François Truffaut, Jean-Luc Godard and David Lean, filmed Bowie as an alien and shot The Beatles’ fabled performance on the Apple Corps rooftop. Anthony Richmond BSC ASC has led an extraordinary life but says he walked on the shoulders of giants.

“I couldn’t have had the career I’ve had without the help of John Wilcox, Nic Roeg, Freddie Young, David Lean,” he says, “So, giving back to the next generation of cinematographers is my duty and a pleasure.”

Nearly 80, Richmond passes on his vast film experience to students as chair of the Cinematography Department at the New York Film Academy in Burbank.

“It’s a very good MFA program but a film school degree is no guarantee of a career – and nor is it necessary if we’re honest. You can become a cinematographer by way of working your way up much like I did, although I’ll admit that is harder these days.”

Working-class background

Richmond’s father was a taxi driver with two great loves in life: football and films. “Both were like a religion to him,” Richmond says. “I remember watching Shane (1953) and loved the way it looked. I thought ‘My God I would love to do that’ but I knew no-one in the industry.”

Leaving school aged 15 he got a job as a messenger boy at Pathé News. “I’d run up and down Wardour Street carrying cans of film. I was offered a chance to become a newsreel cutter. I didn’t want that, but I did get an ACTT [The Association of Cinematograph, Television and Allied Technicians] union ticket and that helped me get a job as clapper boy at Danziger Studios.”

Danziger’s production Call Me Bwana (1963), starring Bob Hope and Anita Ekberg, was Richmond’s first screen credit. He performed similar duties as freelance on features including From Russia with Love before a meeting with budding cinematographer Nic Roeg BSC changed his life.

Judith, starring Sophie Loren and Peter Finch, was “a terrible movie” but Richmond gravitated to the second unit which was being photographed by Roeg in Israel for DP John Wilcox. “They were a lot of fun, so when Nic invited me to join his next movie I jumped at the chance.”

This was Doctor Zhivago, the Russian Revolution romance from which Roeg was fired by director David Lean after a month. Lean, however, demanded that Richmond stay.

“He said it would be good for my career,” he says. “I really disliked Lean for firing Nic and Lean soon learned how I felt from someone on the crew but he and Freddie Young BSC (who took over as DP to win the 1965 Oscar) took me under their wing.”

Zhivago was an epic 50-week shoot in Spain. “We sometimes made just one shot a day, but I learned more from [Lean] than anybody. A wonderful director and a master craftsman.”

Incredibly, his apprenticeship continued under François Truffaut for whom Roeg was shooting Fahrenheit 451. He focus-pulled on Casino Royale (“doing all the stuff in the casino”) and was 1st AC for Roeg on John Schlesinger’s Far From the Madding Crowd in summer 1966.

In October that year, when director Basil Dearden was looking for a DP for his David Hemmings crime comedy, Only When I Larf, Schlesinger recommended Richmond.

“I was living in Nic’s apartment and get this phone call out of the blue. I told Basil I’d never been a lighting cameraman. He just said, ‘Would you like to have a go?’. And that was it. It’s an inconsequential story but that was my big break to being a DP. I was only 23.”

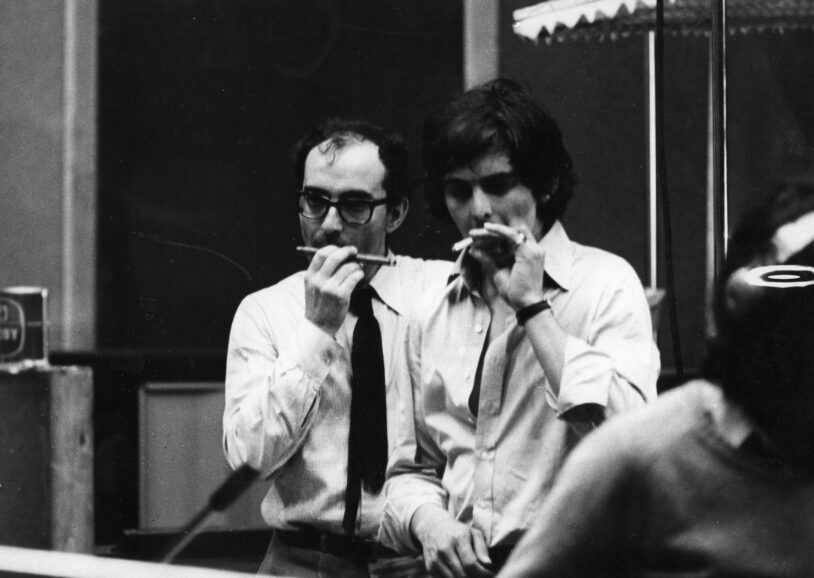

Sympathy for the Devil

Perhaps because of his work with Truffaut, when fellow New Wave director Jean-Luc Godard came to town he hired Richmond. One Plus One, a behind-the-scenes look at the Rolling Stones developing ‘Sympathy for the Devil’, is a career highlight.

“Godard was my hero. He was very left wing, bordering on communist and he hated the producers,” he says. “I liked him.”

Footage of the Stones recording ‘Beggars Banquet’ at London’s Olympic Studios was mixed with staged acts of political rebellion. “It was very low budget with no script,” Richmond says. “A car would pick me up in the morning and Godard would be there smoking cigarettes and he’d literally write on the packet what we’d do that day.”

In typical rock ’n’ roll fashion, the filmmakers didn’t know when the Stones would show up to record. “Sometimes they wouldn’t come in until midnight – but we always knew where each of them was going to be because [recording engineer] Glyn Johns has set up the mics. We surrounded the stage with 8×4 plywood sheets so we could track an Elemack dolly. I operated a Mitchell BNC with a dolly grip and focus puller. Jean-Luc would tell the grip to push the dolly around the stage and I would find an image. If I felt the dolly stop, I’d stay there. It was really exciting. It was the first time I think anybody had filmed the process that a group goes through to record a song.”

Remarkably, Richmond was to follow this with a fly-on-the-wall making of The Beatles’ album ‘Let It Be’ directed by Michael Lindsay-Hogg in 1970. Peter Jackson leaned almost exclusively on footage shot by Richmond for his recent documentary Get Back.

“They are two very different stories,” Richmond says, protective of his friend’s film. “Michael’s was a dark, sombre piece that shows the group breaking up. Get Back was based on 50+ hours of supposedly of unseen material – I’d seen it! They took the original neg and restored it. It has a very digital, very bright look to it.”

Shooting the group’s epochal performance on the rooftop felt momentous. “We rolled 14-15 cameras including five 16mm on the roof itself. I was operating one looking up at Lennon the whole time. It brought that part of London to a standstill even if the people in the street couldn’t see anything because of the angle of the roof.”

Walkabout with Roeg

A year later, Roeg asked Richmond to shoot second unit on his first solo directing project, Walkabout (1972). “It was all exteriors with no lights or generators. It was an amazing job, not least for the experience of travelling all around Australia from Alice Springs to Darwin and the Northern Territory.”

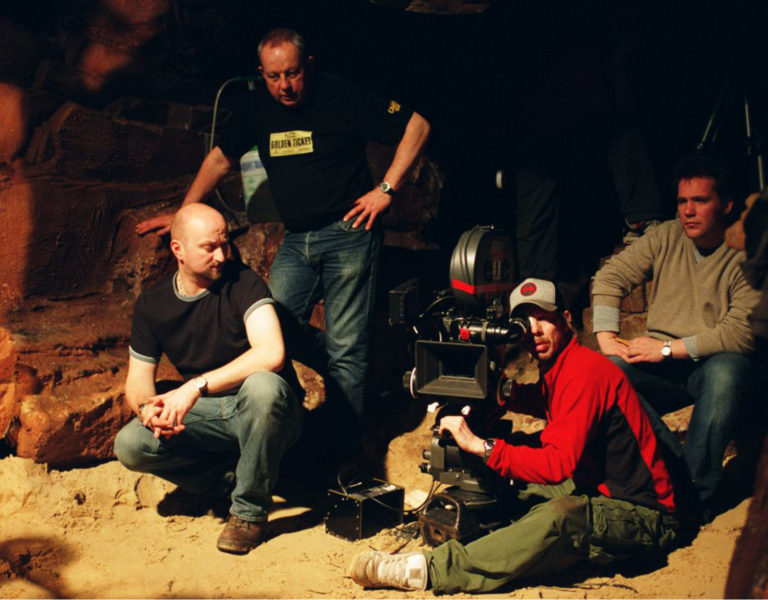

Next up was the unsettling puzzle of Don’t Look Now for which Roeg wanted Richmond as DP. “I was amazed, and I had some trepidation about shooting a movie for someone who had been a cinematographer,” he says.

The only piece of advice Roeg gave was ‘Don’t be afraid of the dark’ which was not only technically astute but spoke to the film’s supernatural narrative.

“This was another low-budget movie with a very tight schedule. When night shooting, we had no condors, and we couldn’t use big arc lights. We put 10ks up on balconies, but I had to let it go dark. It’s fabulous movie. Not because I shot it, but it still stands up today.”

Richmond won the BAFTA for best cinematography and ensured the continuation of a “wonderful relationship” with Roeg.

“He was an older brother and then a great friend. In Venice we shared an apartment and were always talking about film. If you want to know what a director has got in mind, then talk to them about cinema.”

They made five films together, the most iconic being The Man Who Fell to Earth. “Bowie wasn’t Nic’s first choice. He wanted [author] Michael Crichton who had acted a bit but when he pulled out, Nic talked Bowie into being the alien. He’d just seen a BBC documentary Cracked Actor about Bowie’s drug and alcohol addiction.

“Part of the brilliance of the film was that Nic hardly directed Bowie. They’d rehearse lines but didn’t give too much direction. Bowie was still doing drugs every now and again. At times you could see he was just about holding it together.”

Richmond framed Bowie’s androgyny with startling composition in New Mexico landscapes with added lens flare. “In those days everybody tried to get rid of flare, but we had this scene where Bowie comes out of a pawn shop and sits by a river, the sun was so low and we just went with it. It looked ethereal.”

Coming to America

His first brush with Hollywood was the The Eagle Has Landed, a 1976 World War II thriller starring Sutherland and Michael Caine directed by John Sturges in what transpired was his last film.

“He was the epitome of what I imagined an American director to be,” says Richmond of meeting Sturges at Claridge’s. “Tall, hunchback, wearing a big cowboy hat and suede leather jacket with tassels. Drinking whisky out of the bottle. We got on like a house on fire.

“He told me, ‘While in prep you can take as long as you like but when we’re filming if I like ‘take one’ we’re moving on’. That drove Donald crazy. He’d come off the back of Fellini’s Casanova where they’d do 20-30 takes. He always wanted to do one more, but John wouldn’t have it.”

Sturges and Richmond re-teamed to adapt another WWII action story. They went to Munich to prep and in the North Sea on an actual U-boat that had been sunk by the British during the war and repatched for service.

“I’ve never been so scared than being out at sea on that boat shooting plates,” he says. “There was a scene in the script set on another U-boat that Sturges refused to take out which ultimately meant that he departed the project.” [Wolfgang Petersen and Jost Vacano made the film as Das Boot].

On location in Greece to shoot The Greek Tycoon (1978) for director J. Lee Thompson about shipping magnet Aristotle Onassis, he formed a friendship with star Anthony Quinn. Later, he also couldn’t pass up the chance to work with Robert Mitchum on the horror film Nightkill (1980), becoming good friends.

Having moved to LA and married Nightkill actress Jaclyn Smith, Richmond became resumed his friendship with Quinn, Mitchum and the legendary actor “Charlie” Bronson “until the day they passed” and remains pals with Michael Caine, perhaps because they share Richmond’s working-class roots.

“Caine is the only one who got me a movie. When shooting Eagle, he asked if I wanted to do a movie with him. I said it wasn’t up to me, it’s the director who hires me. He said, ‘Do you want to do it or not?’”

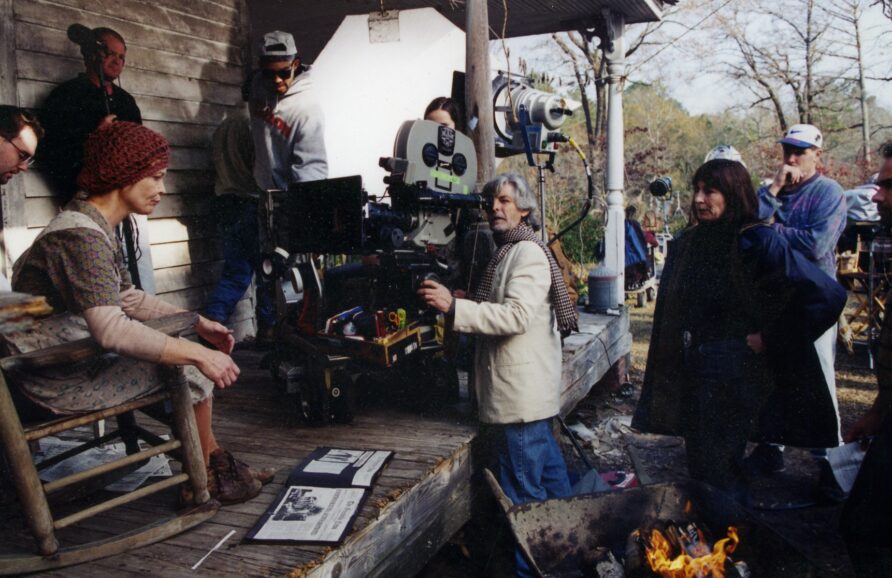

That encounter led to shooting action caper Silver Bears (1978) on location in Lugano, another of the 90 varied features he has lensed. Other notables include Candyman for Bernard Rose, Stardust for Michael Apte, Rough Riders for John Milius, Indian Runner for Sean Penn, Ravenous for Antonia Bird, Men of Honour for George Tillman Jr, Agnes Browne for Anjelica Huston and the hit comedy Legally Blonde.

“It’s a wonderful job being a cinematographer and it used to be a lot of fun. Perhaps it’s more corporate now,” Richmond reflects. “Some directors are very involved in composition and others are totally interested in performance. I’m lucky I’ve got on extremely well with every one of them.”

Some would say luck had nothing to do with it.