LOST IN A MOMENT

Conveying the punk power, art, and anarchy surrounding the Sex Pistols’ rapid rise to fame saw frequent collaborators Anthony Dod Mantle BSC ASC DFF and director Danny Boyle set out to capture the extraordinary feeling when the music and energy in the room makes time stand still.

“There’s nothing more magical and relevant to making films than the feeling when a piece of music or an artistic experience becomes an emotional limbo, and you lose all sense of time and space. You hear a song, and you forget anything you’re worried about. Time stands still; you just flow.”

When these words – full of passion and determination to bring yet another captivating story to the screen – were sent to Anthony Dod Mantle BSC ASC DFF by director Danny Boyle, they reinforced why the pair should collaborate once again.

Normally armed with a “mountain of still images” to inspire, on his latest project, which would tell the wild tale of English punk band Sex Pistols’ rapid rise to fame, Boyle only had words. Drawing on their artistic vision and ingenuity, together they found the visual language and interpreted the images in a unique and bold cinematographic form.

“Danny is an investigator of film and I relate to what he said film and music are capable of. They do suspend time,” says Dod Mantle (127 Hours, Rush, Slumdog Millionaire). “At the end of his email, Danny said something else wonderful: ‘The greatest feeling in the three minutes of time that pop music takes – that makes you float, free of everything locking you down – I can’t express in still images. But if there’s anyone who can in moving images, you can.’

“That is a lovely but also rather terrifying declaration of love and trust from a man of Danny’s calibre. Even though we know each other well, this business can be hard and sometimes you need a bit of encouragement from each other.”

Based on the Sex Pistols guitarist and founding member Steve Jones’s 2017 autobiography Lonely Boy: Tales from a Sex Pistol, FX’s limited series Pistol, streaming on Disney+, depicts the three-year chaotic rollercoaster journey the group of rebellious, loud, working-class British lads embarked on in the late ‘70s and the pivotal role their band played in the punk revolution which transformed music and culture.

Dod Mantle was not part of the punk movement as he was living in France in 1976, Denmark between 1977 and 1978 and travelling in India “wearing flowery jeans” in 1979. However, he and Boyle are lovers of the music that period spawned and respect the power of bands such as the Pistols who shook the British establishment and introduced the world to music with freedom of speech at its core.

“1981 was my first London contact with punks. By then it was a more commercialised wave rather than the Pistols era. I was living near Worlds End [Vivienne Westwood’s first boutique and a hub for punks and rockers] whilst studying at the London College of Printing and could see the extreme juxtaposition and diversity of wealthy people whilst the poor grew poorer. There was violence, anger, and envy everywhere in London.

While the punk movement was highly commercialised at that point, Dod Mantle could still feel its power; there was still a voice. “I just knew the music was extraordinary and the Pistols were an inspiration. And now, in 2022, freedom of speech, political voice, and feeling you’re part of a system you can affect is still essential for young people. The balance of art and politics has never been more important.

“As the series’ scripts developed, I saw how the team, including writer and showrunner Craig Pearce, evolved the story with Danny. And then as we explored the way Johnny Rotten wrote their song lyrics and where those words came from, it became even more evident that dedicating a year and a quarter of my life to the project was the right decision.”

Surrounded with visual stimuli

When prepping, Boyle and Dod Mantle immerse themselves in the story by absorbing visual stimuli and spending about 80% of pre-production on recces. “Whether we’re on double decker buses, in endless pubs and dreary, appropriate venues around London for this project, or, as Danny says, ‘toilets, toilets, and more miserable stinking toilets’, that’s how we prepare to make our productions,” says the cinematographer.

Boyle always prefers to shoot in real spaces. “He loves the excitement and vitality of it, even if it means a lot of work for the incredible locations department,” says Dod Mantle. “We’re at locations and in the spaces where the story will develop, working with a tremendous crew including people such as executive producer Tracey Seaward, Adam Gascoyne from Union VFX, and production designer Kave Quinn.”

Around 70% of Pistol was captured at real locations, with recces determining the selection of the New Cross Inn in South London as a venue in which multiple key locations were created including the building in London’s Denmark Street where the band rehearsed; Marquee Club in London; and Ivanhoe’s nightclub in Huddersfield where the band performed their last UK gig – a benefit for the children of striking firefighters.

“We needed easily controllable spaces, especially during COVID times and for scenes such as the big gobbing match as the band performed at Marquee Club. While shooting that, some of the crew ran around covered in black, holding spit rigs pumping infection-free water,” says Dod Mantle.

In November 2020, a small crew captured some scenes pre shoot in Yorkshire, doubling for Huddersfield and Whitby. Southern London and the southeastern coast including Dover and Frimley were used to represent Yorkshire and support the earlier shot materials.

The 100 Club performance sequences were filmed at the real 100 Club – a sacred place the band played many times – and the recreation of the band’s infamous interview with Bill Grundy was shot in the building it originally took place at, Thames Television Studios on London’s South Bank. Other sets created in the building include the band members’ home interiors, Denmark Street studios interior and exterior yard, and the studio where Sid Vicious recorded ‘My Way’.

The crew also travelled thousands of kilometres across America, visiting locations such as Texas to recreate the band’s wild US tour and road trip. “It was sad as they were imploding as a social unit at that point,” says Dod Mantle. “We filmed supporting exterior shots of their performance at Longhorn, Texas at the real venue – a glum, sordid place that was extraordinary to experience. We then recorded the concert interior for their penultimate US performance before the collapse in the New Cross Inn.”

That last day of shooting was an “astonishing experience” for Dod Mantle, who captured much of it handheld onstage alongside the “disciplined stiff cams” the Americans used at that time to shoot concerts. “We noticed the weird neutral camera methodology of the US studio recordings as well as the inhouse camera crew work at Winterland – their biggest and last US concert. Although they didn’t use handheld cameras on those performances, Danny and John [Harris] intercut the footage captured by slow, unempathetic zooms with handheld sequences I shot, dancing around the stage like a little elf with the musicians for 11- or 12-minute takes.

“Something amazing happened in the room that day as those powerful last scenes of the band capitulating and almost having out of body experiences played out. I was almost weeping while shooting it as there was so much emotion there.”

To help recreate each key space featuring in the Pistols’ journey, production designer Kave Quinn (Trainspotting, Emma, Judy) – a punk rocker at the time the band rose to fame – drew upon her memories of the period. Dod Mantle surrounded himself with Quinn’s mood boards “like a shrine, studying them in detail for hours,” impressed by her knowledge of the environments they would need to create and her team’s exquisite sense of colour and texture.

“When watching some films, I see great camerawork, direction, acting, but I can spot if the finish is not complete,” he says. “Kave never lets that slip. It’s that final gunge that makes things look right in some environments we shot.”

Denmark Street – spanning two floors and a large backyard – was one of the largest sets Quinn and her team built. They also shot scenes in the squat Johnny lived in at a real building in South London which “Kave and her art department covered with binbags and filth, transforming the environment.”

The words, the music, the anger

Dod Mantle’s mentor, photographer Sir Donald McCullin CBE’s images of “working class, suffering, poverty, and brutality” have always inspired him and were relevant once again when lensing Pistol. He also frequently delved into “endless pictures from the period” and literature about the Pistols.

“Julien Temple’s astonishingly brilliant Pistols documentary The Filth and the Fury was another significant stimulus for our series – he shows the band as so vulnerable,” he says. “And although visuals were helpful in understanding the look of 16mm productions of the time, sometimes sentences or quotes were as important.”

Dod Mantle admits 16mm would have been an appropriate format to shoot Pistol, but as the budget would not allow for this they opted for digital capture. Aspect ratio selection is a decision he would not compromise on, considering it an incredibly important part of his creative process as “composing every frame becomes a cinematographer’s way of vision. It’s the way we breathe.”

Among the reasons he outlined to Boyle for wanting to adopt the 4:3 Academy ratio was the enormous amount of material shot in that aspect ratio from the period in which Pistol is set. Dod Mantle believed it would “help transport the audience back in time and make the image feel less like cinema.”

“Danny fully supported me, and I know I wouldn’t have got it approved without that,” he says. “Some cinematographers use 4:3 for classical composition such as the wonderful Bruno Delbonnel ASC AFC and his astonishingly beautiful work on The Tragedy of Macbeth. That use of that aspect ratio – portrait photography that is very specific with the right millimetre focal length, lighting, height of the camera in relation to the object – is a glorious thing.”

However, Dod Mantle did not select 4:3 for classical portraits as “nobody could capture the band in that way at the time because those guys were always misbehaving. The graphic shape of the content within the frame was uncontrollable.”

Stills of the Pistols and bands of that period are “kind of lost in the space,” he says. “The faces and bodies are lower in the frame and there’s a lot more headspace. That helps the audience subconsciously perceive the characters as slightly lost at sea, lost in a non-composition. Something else comes forward, which is far more evocative – it’s more about the words, the music, the anger.

“We couldn’t shoot a 4:3 frame where we placed the heads close to the top of the frame, which is what you often do when shooting singles and medium close-ups. It’s not that type of series. So, the heads automatically got lower in the frame.”

Two decades ago, when Boyle and Dod Mantle first shared their filmmaking passions and motivations, they were united by a shared belief about the importance of camera movement and “what framing is thereafter, because camera movement immediately creates a space around heads.”

Movement once again took centre stage when making Pistol as “the cameras, like the band, don’t stand still for very long”, especially during the performances which saw Dod Mantle often operating handheld alongside B camera operator Iain Mackay ACO, moving around the stage and amongst the audience. Additional fixed cameras were positioned around the stage along with a handheld with a zoom lens replicating filmmaker Julien Temple’s camera documenting the Pistols’ performances.

“This series was about letting the Pistols go in that space and then allowing editor Jon Harris and Danny to also blast through and integrate the non-controlled documentary material shot in the ‘70s in the edit,” says Dod Mantle.

While letting go in some ways and fighting the “cinematographer’s innate controller gene” was critical, lighting, camera, and grip logic still needed to be maintained. “I talked to my whole crew [including brilliant and loyal camera operator Iain Mackay ACO, talented grips Jim Philpott and Greg Murray, DIT Marc Jason Maier, and 1st AD Deborah Saban, fantastic 1st AC David “Spooky” Churchyard”, B Cam 1st AC Rami Bartholdy, B Cam 2nd AC Jessica Oxley, and up and coming talent camera trainee and 2nd AC Nadine Odongo and trainee Luke Teusch] very carefully about why there was so much headspace and what Danny and I were trying to achieve. We were just spreading that vision and letting go. That’s also what punk was about.”

Headspace also impacted the lighting, requiring gaffer Harry Wiggins to move the grid higher. He and Dod Mantle also studied archive footage, noting where lights were placed in the Pistols’ concerts and then replicating the look and palette of many of the venues in the New Cross Inn.

Wiggins suggested any “irrelevant and too modern” colour filters be eradicated. “There was a restricted availability of colour gels, and colour filters back then, so we decided to stay true to that more primitive look,” says Dod Mantle. “We used LEDs because we had to but replicated tungsten and the colder available light.”

Suspending time

Rejoicing in finding reference images together and bouncing ideas off each other, Boyle and Dod Mantle had access to an extensive array of archive material. But while they “knew who the Pistols were, they just didn’t instantly know where to go.” They were, however, aware they must convey a feeling of “suspending time” and depict “a mosaic, frenetic, political, Rauschenberg-like world” as the Pistols rose to fame.

“This was a story about four ragamuffin geezers off the street and the influence of a few significant people around them such as the architect in the shape of manager Malcolm McLaren and Vivienne Westwood whose styling helped shape the band’s image,” says Dod Mantle. “These lads pulled together and all they wanted was to make a noise and ultimately destroy. There was no organisation; it was chaos.

“I was horrified and impressed by the energy and genius of someone like Malcolm McLaren. His gravestone features the quote, ‘Better a spectacular failure than a benign success,’ and I really believe in that. His ability to see the Pistols’ potential was essential to their success, despite his actions that followed. However, we also know the genius creative at the centre was Johnny Rotten.”

As Boyle and Dod Mantle explored what the visual world of Pistol would become, feeling out how to turn the frantic, outrageous and at times heart-breaking story into a series, they tested multiple cameras early in the process. This saw them work with an assortment of six image capture systems including a combination of old and new Canon technology to create a striking vintage feel, alongside an ARRI Alexa Mini LF A cam paired with K35 vintage lenses which were first introduced in the ’70s.

The Canon K35 macro zoom, and other zooms were always utilised for gigs and rehearsals where Dod Mantle and Boyle knew the actors, especially Anson Boon playing Johnny Rotten, could in principle only perform two numbers a day before their voices faded. “Therefore, many cameras were needed to nail the music in as few takes as possible, often with extra operators and fixed cameras in addition,” says Dod Mantle.

Within the “logistics focused world that is filmmaking within a tight schedule,” Dod Mantle and Boyle wanted to feel they could be “impulsive and erratic” as studying images of the Pistols and seeing the scripts develop, showed the band “seemed to be imploding as time passed.” It was clear they would not make a “linear, intellectual, or conventional series.” It would be a “montage”, initially shaped through testing an assortment of cameras.

Dod Mantle’s golden rule when testing is “be aware of the specifications but do not ever let that dominate your chain of thought in the search. Dig into everything with an open mind and heart and use your eyes to look on the screen and feel how and what it conveys. All else is intellectual.”

In their search for the most suitable systems Dod Mantle and Boyle tested cameras including VHS portable cameras; Hi8; Digital Betacam; Mini DV; Canon XLH1 with zooms to heighten moments (which had been employed with a spinning P&S adaptor for 28 Days Later and were used in Pistol for moments when Dod Mantle dragged the slow shutter combined with movement); Sigma FP on a lightweight handheld rig with adapted 18-35mm zoom from P&S for ragged stage and audience work, diopters, or Lensbaby; handheld Canon Eos stills cameras; Canon Barcam [developing time lapse ideas]; and ARRI Alexa Mini LF with assorted vintage primes and zooms.

The mixture of systems – which Dod Mantle refers to as “an impulsive mosaic shooting system” – also included 18 EOS R5 mirrorless cameras, the EOS-1D X Mark III, and vintage XL1 camcorders. By working with multiple systems Boyle says he wanted to “capture the limitless energy from the punk community and the furnace of potential that was the Sex Pistols. I’m very visual and with Anthony, we constantly talked about how we were going to manifest this.”

They combined archive footage with sequences captured with an old Canon XL H1 camcorder and high-res EOS-1D X Mark III stills camera to create what Boyle refers to as an “incredible mixture of different textures and colours that take people back to 1975, but make it feel like it’s happening now. We tried to make the experience really immersive through the intensity of what you’re seeing and hearing in an old school way – it’s a flat screen, but you do everything you can to not make it flat.”

Capturing unforgettable moments

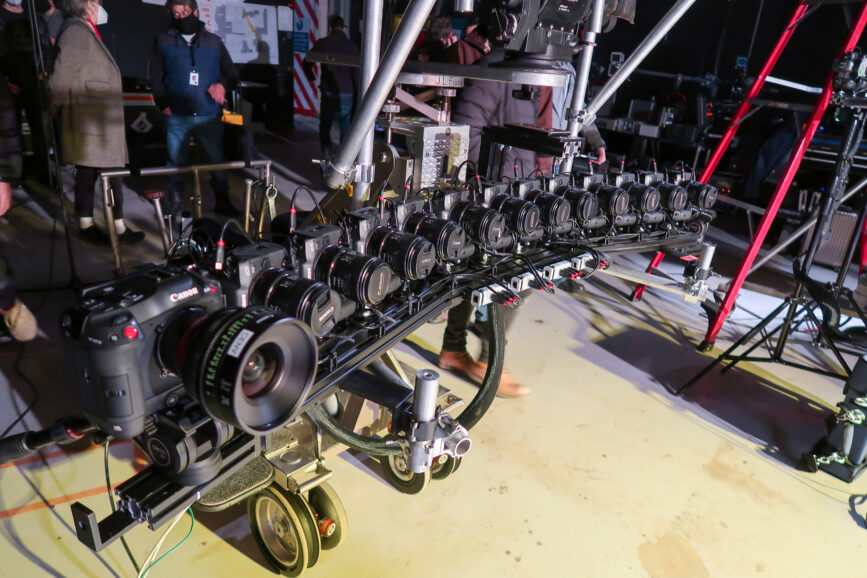

Aiming to bring a new dimension to live music and action sequences to convey the mayhem surrounding the band, Dod Mantle approached Canon during pre-production to help create two, multi-camera solutions to achieve the bullet time effect that would manipulate time. Building on a relationship the filmmakers formed with Canon while making 28 Days Later, this time around they were assisted by Aron Randhawa, European product marketing specialist at Canon Europe, and supported by ARRI Rental – guided by Russell Allen – and UK-based technical production studio The Flash Pack.

One barcam multi-cam rig comprised of 12 EOS R5 cameras mounted vertically to make it as compact as possible, and the other was an ultra-portable handheld six camera system which allowed Dod Mantle to be mobile whilst operating.

The EOS R5 was selected for its compact size and weight, as well as its ability to capture high resolution full-frame video footage in Canon Log at 24p, with multi-camera sequences captured in 4K video, rotated, cropped to 4:3 aspect ratio, and manipulated in post to slow down time during action scenes. Equipped with EF 24mm f/2.8 lenses featuring diffusion filters, Dod Mantle could keep the multi-cam rig lightweight whilst producing a soft look and feel.

He wanted to create a time lapse system “without subjecting production to a day in the studio using complicated equipment. The grips and the team at The Flash Pack were helpful in producing a system which could also manage an immense number of terabytes of material which Jon [Harris] and Danny could work with in the edit.”

The slightly curved 12-camera rig was either on a Technocrane or dolly and could wrap around, for example, Steve playing guitar or Johnny singing, and freeze a moment. Key grip Jim Philpott and the cinematographer built brackets allowing him to move around on set, shooting conventional material for three quarters of the day in a location like the Vauxhall Tavern, and then bringing in the Technocrane with the 12-camera barcam for one or two takes. Dod Mantle refers to the technique as a “rock ‘n’ roll attempt at creating something very sophisticated.”

“I seem to spend my life trying to do things like this which is why I often end up in the world of prosumer equipment. You have your solid-state cameras, big fat sensors, and beautiful vintage lenses, but I also shot with the barcams in the back of Minis and Ford Transits. It was absurd. You can’t use state-of-the art rigs with six normal sized cameras for that. It just wasn’t that kind of shoot.”

Once again, every decision during the creation and use of the barcam was motivated by a “desire to capture something unforgettable – the energy in the room or that moment in a concert when the world around you stops”, inspired by Boyle’s initial words to Dod Mantle. In addition, a Chronos 2.1 HD high-speed camera, shooting at 3000 fps with C-mount lenses capture “spontaneous, complex, high-speed sequences” for handheld crowd and stage work.

The Canon EOS-1D X Mark III – shooting handheld at 20fps in continuous burst shooting to capture crowd and stage work – was key in seamlessly marrying vintage archive footage with the newly captured footage of the cast, enabling Dod Mantle to replicate the look of film stock while creating a dream-like motion using Lensbaby lenses. He and Boyle had also used the stills camera on 127 Hours and Slumdog Millionaire, “shooting in burst mode and editing in camera to signify memory and the character’s interpretation of the truth.”

“For Pistol, the quality of the image and lenses enabled me to create incredibly visceral, powerful images, while dancing around the actors. It started as a tool to shoot the concerts, but it became something I shot with in every single location, whether it was a prop, a sign, or a pair of underpants in Vivienne Westwood’s boutique.

The Canon 1D was not only used to capture visceral moments with the band and the energy between them and other characters. Dod Mantle also used it “as a kind of hoover – I refused to leave any set or location without scanning the whole territory at the end for anything or anyone that I felt we were leaving behind unregistered. This could be a close detail like the vinyl spinning on the juke box or the gang of northern hairdressers from the failed concert. I wanted to see the doubt and innocence on their faces juxtaposed with the energy of the punks.”

Dod Mantle leant on Canon’s XL1 and XL H1 MiniDV camcorder to transport audiences back to the ‘70s. “I knew Danny was going to suggest the Canon XL1 Mini DV camera we used on 28 Days Later because it did an excellent job on that film and was the ideal system for capturing the zombies. He always had a love affair with that camera,” says Dod Mantle.

“I also work a lot with Lensbabys, experiment with tilt-shifts, shoot through plastic bags, shoot underneath armpits – something I’ve done since The Last King of Scotland,” he adds. “These techniques came into play again, especially for the trippier storylines.”

Other kit added into the mix included vintage Helios lenses, Sony Venice to capture some night scenes, and DJI Inspire 2 drone with a Zenmuse X7 S 35 sensor, operated by Peter Keith. Filters – including Black and White Tiffen Pro Mist – were generally on the front of the list. Dod Mantle also used diopters to limit focus range, soft edge graduation, and sprayed grease and oil onto glass filters.

“I had tried to filter behind the lens, but I ultimately went for the glass in front of the lens and had to work quite hard to rectify the halo effect in the high white lights,” he says. “Though period correct for the time, we sometimes struggled in the grade to eradicate flares for fear of it distracting the audience away from the faces.”

Dod Mantle was also having extensive conversations with ARRI in London and Munich, investigating and experimenting with image capture in the attempt to avoid extensive in camera glass filtration. “We discussed resolution, colour management, definition, logistics, and sensor DNA. I knew I was going to base a large amount of the shooting on ARRI’s LF and Mini LF, but I was hunting aesthetic deterioration in image capture whilst not giving up reliability and latitude, knowing that the shooting would be fast, if not rapid, and on a demanding schedule.

“I wanted to see what I could commit to in shooting in camera without losing too much control and whilst maintaining the trust of the studios – a common complicated balance throughout my career.”

For Dod Mantle, The Alexa LF “delivers the wider solid floorboards to the scenes – tough, robust, reliable, and with little risk.” The other cameras, as a collective, are “the spark plugs to eradicate any over orchestrated feeling of a lucid period film which together become the voice of a time gone but a feeling very much still here. The alchemy between these two camps of thought and technique is what could create the multiple camera crashes in editing.”

He also extends his thanks to Russell Allan and the team at ARRI Media in London and Munich for their support throughout and the use of the mixed reality LED studio to shoot some scenes of the band on tour.

When shooting a series like Pistol, “the rulebook is a little more flexible”. Dod Mantle tried to embed the audience in a situation in a similar way to when he lensed the motor racing in 2013 Formula One biopic Rush “to get the audience as close as possible. It’s why I sometimes use extremely close focus; to feel like you are there. It’s about being immediate and feeling you are privy to something that’s happening spontaneously like combustion in front of you.

“The Pistols were ridiculous sometimes; they’d start a sentence and then end it in a burp. I told Danny I loved it when the dialogue wasn’t too explicit, too explanatory. The series was essentially about their journey and the explosion that took place after their first hit record. Visually, that’s also what happens to the palette of the series, it slowly assembles into a cacophony.”

Building the world

Before principal photography began, landscape footage captured in Yorkshire by Dod Mantle and a small crew was sent to Company 3 so the cinematographer’s close friend and collaborator, colourist Jean-Clément Soret, could experiment with the material. “It was one thing to shoot 4:3, but we were also shooting on multiple digital image capture systems, so I needed to work out how the hell to get it to look roughly how I wanted,” says Dod Mantle. “We had to dirty it down, but I didn’t want to go to the classic ‘70s look which could be grainy, grey, and colourless.”

The same approach was adopted when he determined the look for Rush. “Motor racing is too sexy a sport, too vital a world to make grey and desaturated, so I went very saturated and built the world up from archive. We repeated that with Pistol.”

Working with the footage captured in Yorkshire and collaborating with dailies colourist Dave Lee, Soret and Dod Mantle “baked in much of the look at that early stage, so it just needed refining in the grade. We then discussed how to soften the jolts between the archive and the digital footage we shot, and worked with grain, colour, and contrast.”

The visual storytelling was also influenced by the emotion in the songs and scripts, with the “phenomenal velocity and power of the music manipulating how” Dod Mantle moves, frames, and works. While evolving the look, he listened to the music of the Pistols’ and other bands of the time such as The Clash, “thinking about where the words came from.”

Each episode became a track examining what generated the palpable energy surrounding the band. “Episode three in particular depicted the pretty shocking state of affairs these lads grew up in. A political and social climate of immense unemployment, disruptive society, alienation, poverty, greed, things that still exist and are even more vulgar than ever.”

As a cinematographer, Dod Mantle admits he is “a creature of control. But the whole atmosphere of punk is not controlled, and the cast portraying the band wanted to run free too, so the floor wasn’t marked.” Teaming up with frequent collaborator gaffer Harry Wiggins, Dod Mantle tried to control the set when he could by working as precisely as possible to light the spaces. But ultimately, he knew “it would implode into a mosaic” that would be even more magnified in the edit.

“Harry’s a brilliant collaborator and was by my side at all times. I shared everything with him, as I always do with gaffers. I also benefit from their experience, intellect, and capability to position lighting to create the desired effect. I also commend the rigging crew who took on a huge job due to the schedule. We were generally working five-day weeks, and it could be pretty intense.”

But as a creative process, Dod Mantle considers shooting Pistol one of the most enjoyable collaborations he has experienced with Boyle and yet another stellar crew. “We were in the middle of lockdown, it was a difficult time for many, and making a film, especially through a long and demanding shoot, was not easy. But it was a positive family affair. We were grateful to be working and feeling what we were creating was relevant.”