MOASIC OF MEMORIES

The culmination of many years of friendship and creative exploration between cinematographer Andrew Wonder and writer-director Paul Schrader, Oh, Canada allowed the pair to share a personal story with audiences in the form of a cinematic tribute.

Oh, Canada will always have a special place in Andrew Wonder’s heart. Not only is it the cinematographer’s first film to compete in the Main Competition at Cannes Film Festival, it also allowed him to show audience’s a different side to his mentor and the film’s writer-director, Paul Schrader (The Card Counter, First Reformed, Master Gardener).

“To be here at Cannes with the film, in the house that Godard built and where film is art is a dream that surpasses anything I’ve ever let myself dream before,” Wonder tells British Cinematographer in Cannes after the screening. In honour of Jean-Luc Godard, he had even used a Beaulieu camera to capture his red carpet experience on a roll of Super 8 at the film’s premiere.

Having begun his career in the realms of documentary, Wonder’s filmmaking journey has since seen him work with and learn from many experts in their field including cinematographers Harris Savides ASC and Ed Lachman ASC and Schrader.

“Paul came into my life when I was 20 and became a really early mentor. I’ve known him for almost half my life. He showed me that filmmaking can be art. It’s a form of expression for me,” says Wonder. “At MTV, where I started out, you were a producer and cinematographer, there were no directors. So when I was with Paul, I really understood what a director was. We’ve come in and out of each other’s lives. I’ll do second unit for him, help in the edit, read scripts. But at the beginning of last year, he moved back down to Manhattan, and as I live nearby in Brooklyn, we reconnected.”

Wonder showed Schrader a short documentary he made about a friend who received a kidney transplant from his mother. “Paul said, ‘How did you do that? Did you cowboy it or plan it?’ It was a little bit of both. Paul was finishing a new script and wanted to know how I’d shoot it. When I asked him why he wanted me to do this film with all the people available to him, the answer was simple – he trusted me.”

The script was an adaptation of Foregone – a novel written by Schrader’s late friend Russell Banks. In a form of tribute to the writer, the film, renamed Oh, Canada, is a poignant and personal portrait of a dying Canadian artist and documentary filmmaker, Leonard Fife (played by Richard Gere, with Jacob Elordi as a younger Leonard). The audience is transported between present day Leonard’s final days and his past as he gives a final interview to a former student about his life and remembers how, as one of 60,000 draft evaders who fled to Canada, he avoided serving in the Vietnam War.

“When I read the script I saw the different timelines and I also saw grief. I knew how close Paul was to Russell and how much Russell’s death had shaken him. Richard [Gere] had also just lost his father and Paul’s been a father figure and a big part of my life for a long time so I think about the idea of losing him one day, not being able to ask questions anymore,” says Wonder.

“This was an opportunity to combine those feelings with what Richard and Paul were going through, and help create something emotionally resonant. I feel grateful to be one of the few people who knows Paul better as a person than as a filmmaker as usually the Paul I’ve seen is hidden in the scripts, through metaphor and other things. I saw a chance to bring the Paul I knew to screen.”

Exploring new formats

Wonder’s knowledge of formats and experience building lenses and rigs came into play when helping develop the look of Oh, Canada, presenting a new way to incorporate emotion into the visual approach.

“Paul hasn’t really done anything so stylised since Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters in the ‘80s [about the life of Japanese writer Yukio Mishima, shot by John Bailey ASC]. I felt like the script for Oh, Canada really allowed him to do something different to the ‘Man in a Room’ trilogy of films he’s made recently,” says Wonder.

As the film moves between different time periods, Wonder suggested the filmmakers play with formats and aspect ratios. “And when I read the sections of the script with Richard set in the present day, mahogany, dark, and moody came into my mind, the feeling of crawling out of the shadows.”

As well as taking on board Schrader’s reference of Gordon Willis ASC’s work, Wonder wanted to adopt a contradictory approach to the flashbacks. “I felt anamorphic and the faded look of Fat City [John Huston’s 1972 film lensed by Conrad Hall ASC] was a touchstone, playing with the way we think about the past.”

The cinematographer believed making “memories expansive, and using different locations, gave the audience a chance to breathe”. He was most fascinated by what he refers to as “mosaic memories” – when the film visited different time periods and felt black-and-white would be creatively and practically advantageous for certain sequences.

“I didn’t want the audience to get lost and felt creatively black-and-white allowed you to leave time and create a language to go anywhere. Practically, we were doing so much – the mosaic memories are 1958, the ‘60s, ‘90s, 2000s – and I wanted to help our production designer,” he says. “The black-and-white gave us more leeway with the period to think graphically and because it comes from the soul, the tools and tricks of light and contrast created a more emotional world around the memories.”

Breaking down the story

As he does with every film, Wonder created documents and charts during pre-production, breaking the film down by action, atmosphere, and character and producing a database for the 17-day shoot which would take place in New York. He also used Polycam and Previs Pro to previsualise scenes such as those shot in a documentary/interview style in which Leonard, nearing the end of his life, looks into an Interrotron – a teleprompter displaying a video image.

“I rebuilt the entire film in a one-page document and highlighted scenes such as those which would be black-and-white. Originally we planned to do a black-and-white conversion and I tested the ARRI Alexa 35 which we shot most of the film on but using two very different versions of my exposure system. But while it didn’t convert to black-and-white very well, the ARRI Alexa Mini LF Monochrome had a great look,” says Wonder.

Andy Shipsides at ARRI was instrumental to the project and gave Wonder access to the tools he needed. “There were only two Alexa Mini LF Monochrome in the world. Ed Lachman ASC had just finished El Conde with it and Andy suggested I experiment with it too.”

As Wonder designs and builds filters and has created a whole image exposure system with filtration and colour, when the Monochrome camera appeared on set and the cinematographer put it side by side with his black-and-white LUT and placed a filter in front, the possibilities for the project became clear.

“ARRI was good enough for Kubrick; why would we need anything else?” he adds. “And as Richard Gere was giving so much of himself in this film how could we not shoot that on an ARRI camera? I also advise always shooting with the textures on the Alexa 35. It’s essential. I shot the entire film with the Nostalgic texture.”

Wonder paired the ARRI cameras with ARRI ALFA anamorphic lenses and uncoated Zeiss B Speed lenses, rehoused at True Lens Services. “We call them the Wonder Speeds. Over the last decade I’ve owned four sets of Zeiss Super Speeds and carried out testing to build a super set, tweaking them to how I see the world and working with TLS to build rehousing for them, keeping the irises because we can’t lose those triangles,” he says.

When ARRI Rental demonstrated the new ALFA lenses which had been modified to cover full frame, Wonder felt they “added the little bit of funk” he was looking for. “And with my filters, I could create conflict with the funk to make something new. Using the ALFAs I thought it would be interesting to have a softer, more romantic feel to the present to create a contradiction in how we’re used to seeing the past. There’s also a little bit of Super 16 and Super 8 using some Angenieux lenses I had built for me.”

Wonder also incorporated special colour filtration using filters for the flashback which Stan Wallace at The Filter Gallery arranged for Tiffen to build. “Colour correction red filters that are very specific, and I use to tune the camera, allowed me to mess up the skin tones and bring them back,” he adds.

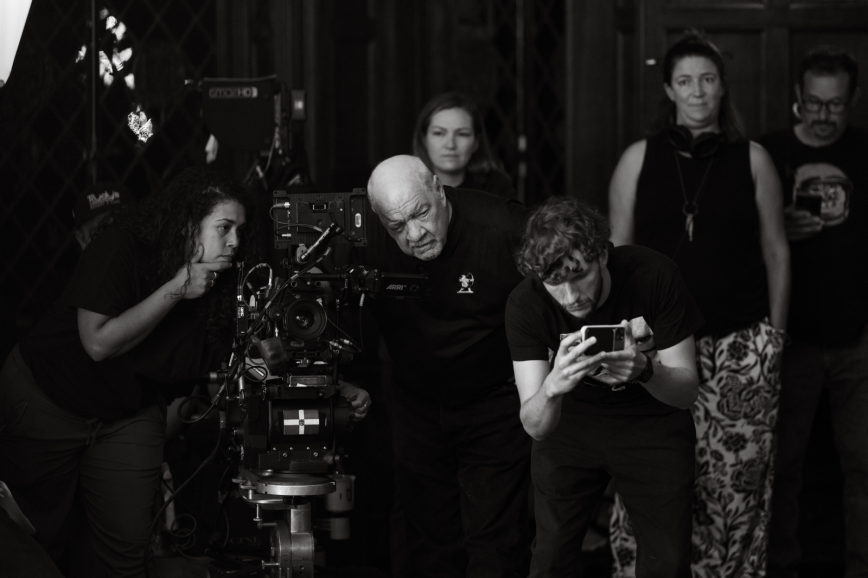

The DP views crew collaboration as a special union. Pivotal to the success of Oh, Canada were “talented creative partner” camera operator Katherine Castro, “touchstone” 1st AC John Fitzpatrick, and key grip Garrett Boehling who embraced Wonder’s “ideas and desire for flexibility”.

Wonder likes to shoot the handheld sequences in his productions, referring to it as “your soul”. He elaborates: “Trying to tell someone else how to shoot a handheld scene is like trying to explain to someone how to date your wife. I spent years walking around with boiling buckets of water and trying not to spill any to get my breathing correct when shooting. Handheld is also like acting and Robbie Ryan BSC ISC has been such a huge inspiration – he can walk up a staircase backwards while shooting!”

For Wonder, technology has enabled crew but also destroyed the auteur filmmaker in some ways, so he wanted to make Oh, Canada “the way humans make films – no gimbals or remote heads. Instead using simple tools so every minute could be reactionary and give the scene what it needed”.

Triangle of creativity

In the first makeup test, Wonder wanted to observe Gere to see how his face took light. “I told him my intention was to give him all the way from light to shadow in every frame. You have a character with many faces who’s revealing himself to the world, so you decide when to share and when not to. From that I kept building a world around him, testing his face, discovering who Richard was, and keeping it as organic as I could.”

Creating that organic look was achieved in unison with trusted gaffer John Raugalis, who, like Wonder, primarily cares about “giving the scene what it needs”. Lighting fixtures for Oh, Canada were a combination of LEDs and HMIs. “I was impressed with the Fiilex LEDs and John showed me the quality that can be achieved with fresnel lights,” says Wonder. “I’m late to the party with Astera Titan Tubes, but John really turned me on to them too and built a little coffin for them so it could become a handheld light source we could run around with. It was all about creating worlds of colour temperature.”

While at film school Wonder also learnt the importance of supporting production design from Ellen Kuras ASC, observing how she worked with director Michel Gondry on Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, “and how she would give herself to the art department during that collaboration”. He continues: “So after the first meeting with our production designer Deborah Jensen, and costume designer Aubrey Laufer, we created a text chain between us so after each meeting with Paul we could update each other. I called it the triangle of creativity – supporting each other, not competing with each other. That’s what the art of filmmaking is all about.”

Words of wisdom Richard Gere shared in the film’s press conference at Cannes spoke volumes to Wonder about the filmmaking process. “Richard said, ‘Clear your heart, open your mind, learn your craft and be brave.’ And that sums up what I took from the experience and was the real spirit of the movie.”