An Amazing Journey

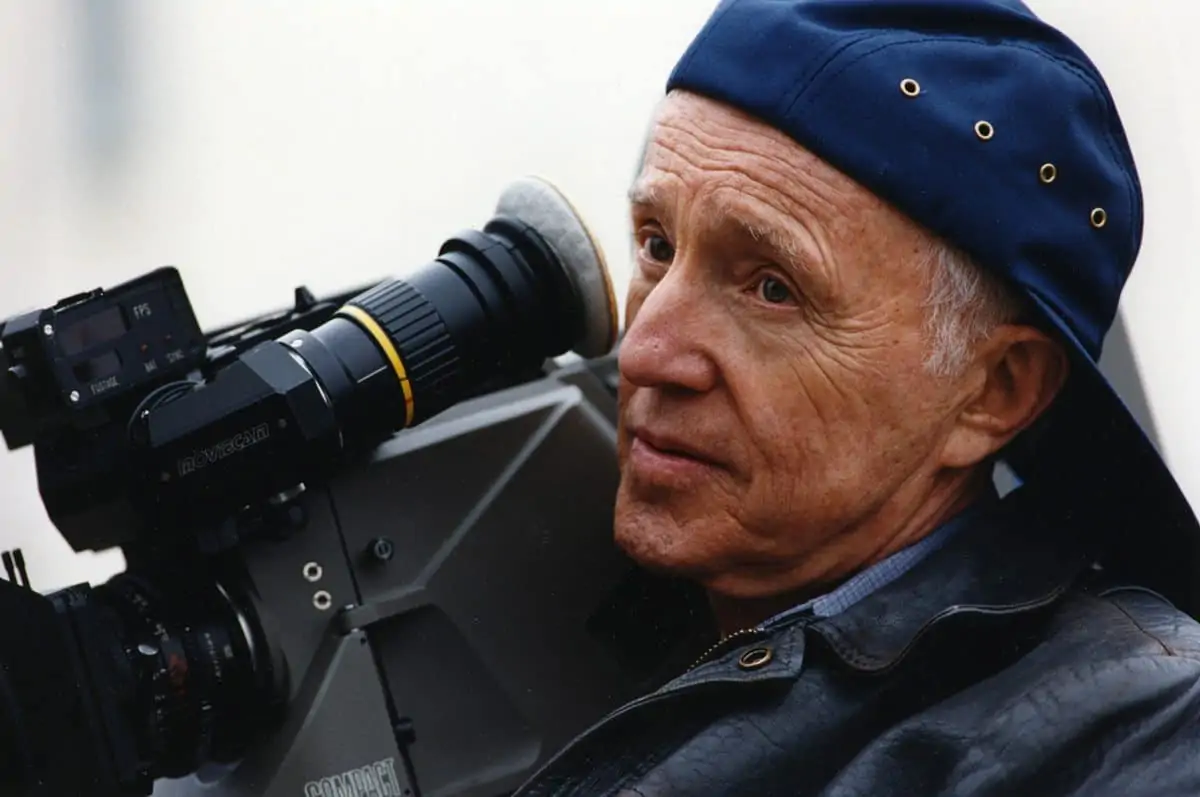

Clapperboard / Vilmos Zsigmond ASC

An Amazing Journey

Clapperboard / Vilmos Zsigmond ASC

BY: Bob Fisher

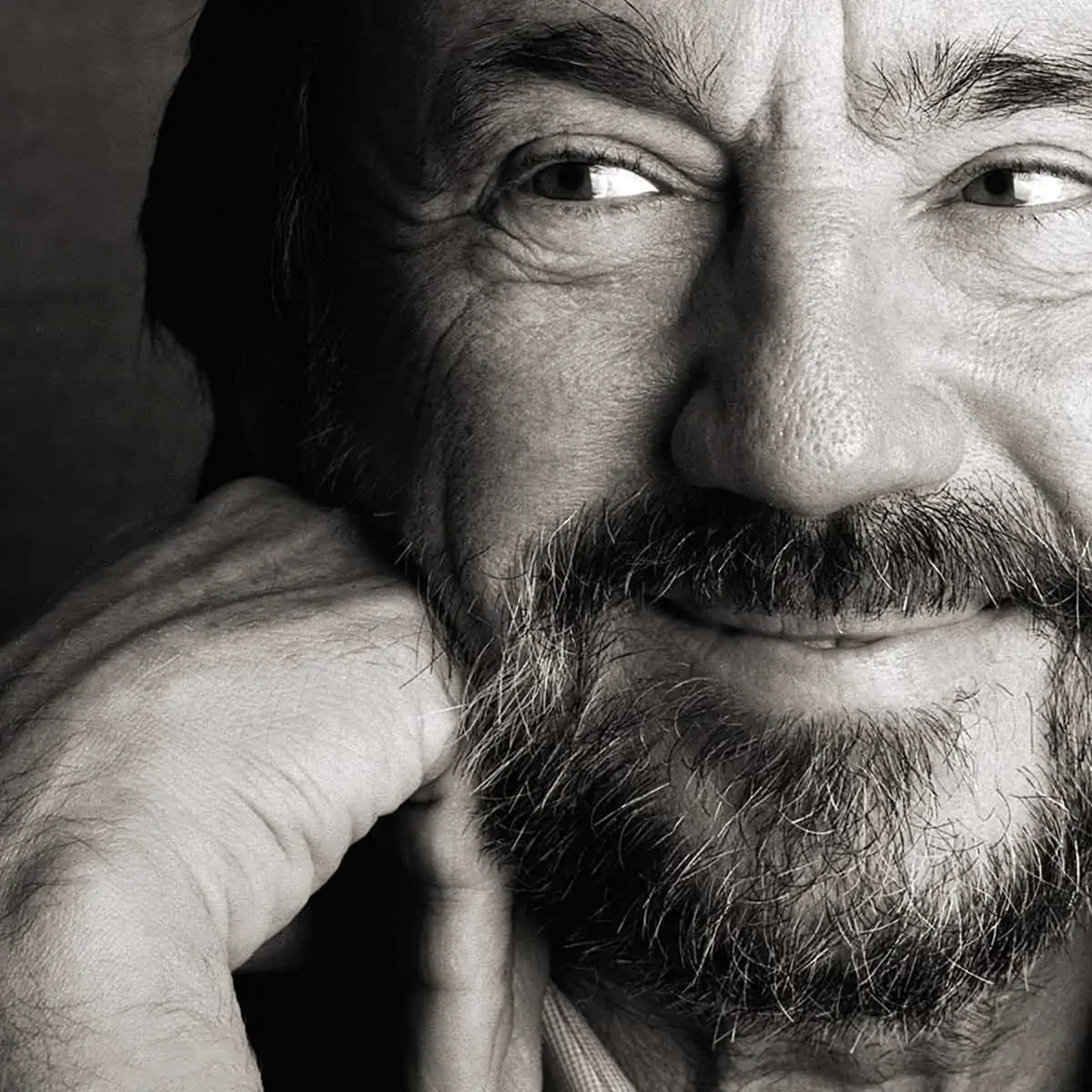

When Vilmos Zsigmond ASC was a teenager living in Szeged, Hungary, a gypsy fortune-teller told him that he was destined to sail across a great ocean to a big city where he would become an important artist. Fortune-tellers were taken seriously in Szeged, but Zsigmond was puzzled. He couldn’t visit a neighboring village without getting permission from the commissar who ran the local government.

Zsigmond’s life story is like a script for a feel-good movie, in which an impossible dream comes true. His father played and later coached professional soccer. His mother ran a pub where Zsigmond cleaned and waited on tables when he was 10 years old.

When Zsigmond was 17, he was bed ridden for three months with a kidney infection. His uncle gave him The Art Of Light, a book about the art of photography written by Eugene Dulovits. After recovering, Zsigmond found a job in a portrait studio.

“My father wanted me to study engineering, but my college application was turned down,” Zsigmond recalls. “The party secretary said my grades weren’t good enough, but it was really because my family was bourgeois. My mother owned the pub, and my father was coaching a soccer team in Morocco.”

Zsigmond was given a job in a rope manufacturing factory. “They gave me a stopwatch to time the work done by other people,” he recalls. “There was a norm for how much work they had to finish every hour. I became an exploiter, because I was pushing those poor people to work harder.”

He saved enough money to buy a stills camera and an enlarger and organised a photography club at the factory. On May Day, they took pictures of the parade in Szeged and hung enlargements on the factory wall. Soon afterwards, the authorities suggested that Zsigmond study filmmaking at the Academy For Theatre And Film Art, in Budapest. The four years that he spent at the Academy opened the window on a new world for him. After he graduated in 1955, he worked as an assistant cameraman and operator at the national feature film studio in Budapest.

In October, 1956, there was an uprising against the communist regime on the streets of Budapest. Zsigmond and Laszlo Kovacs ASC, who was still a student, borrowed an ARRI 35mm camera from the school and documented the revolt, including the brutal suppression of civilians by Russian soldiers and tanks. To put that into perspective, people caught with cameras were arrested and sent to Siberia or shot.

Gyorgy Illes, who was head of the film school, told Zsigmond and Kovacs to leave the country before they were arrested. They made the journey by train, and walked the last 20 miles to the Austrian border carrying 10,000 feet of film in laundry bags.

Zsigmond and Kovacs arrived in the United States as political refugees in January, 1957. Zsigmond worked at odd jobs in Chicago and New York. He and Kovacs met in Hollywood at the end of the year to help a fellow expatriate produce a short film.

Zsigmond spent the next five years working in a still film lab and going door-to-door offering to take portraits of children. He also shot 16mm educational and industrial movies and free films for students while learning to speak English one word at a time.

“I tried to fit in by telling people my name was William,” he remembers.

By the early 1960s, he was shooting ultra-low budget films, including The Sadist, The Nasty Rabbit, Psycho A Go-Go and Rat Fink. He was also on the cutting edge of shooting 30-second stories for the television commercial industry. Director Gus Jekel at FilmFair encouraged Zsigmond to experiment with using shades of light and darkness, composition and other visual grammar to make emotional impacts.

“Luckily, they didn’t ask me how much I wanted to be paid,” he says. “I probably would have said $5 an hour. They paid me $100 a day the first year.

"I tried to fit in by telling people my name was William."

- Vilmos Zsigmond ASC

In 1970, Peter Fonda asked Zsigmond to collaborate with him when he took his first and only turn at the helm on The Hired Hand. Fonda also starred in the film.

“Peter said that I didn’t look like a William,” Zsigmond recalls. “He asked me what I was called in Hungary. When I told him Vilmos, he said that’s a beautiful name.” The Hired Hand was released by Universal Pictures. It was Zsigmond’s entry into the world of mainstream filmmaking, and his first credit with his given name.

His next film was McCabe And Mrs. Miller with Robert Altman at the helm. During their first telephone conversation, Altman said it was a period film set during the early 1900s in a Western mining town. He wanted it to look like faded color photographs.

“I had read an article about how Freddie Young BSC got that look by flashing the film when he shot The Deadly Affair in 1966,” Zsigmond says. “We shot tests and decided to flash the film by 15 percent. I also pushed it to add a little grain to the look.”

McCabe And Mrs. Miller was produced at practical locations in Vancouver, Canada with Julie Christie and Warren Beatty in leading roles. When studio executives saw the first film dailies, they told Altman to fire Zsigmond because the colors were faded and the film was grainy. Altman didn’t try to explain that was the right look. He lied and said that the local lab didn’t know how to print dailies. McCabe And Mrs. Miller earned rave reviews and was a hit at the box-office. Zsigmond was nominated for a BAFTA cinematography award.

Zsigmond’s career shifted into high gear after McCabe And Mrs. Miller. He collaborated with John Boorman on Deliverance in 1972. There is a pivotal scene where the villain arrives on the scene in a canoe. Boorman wanted the audience to feel that danger was approaching. Zsigmond put the camera on a tripod in the water. The lens was just four to five inches above the surface of the river. There is a tactile feeling of danger approaching as the camera panned. Deliverance and Boorman both earned Oscar nominations and Zsigmond was the BAFTA award again.

In 1974, a young director named Steven Spielberg asked Zsigmond to collaborate with him on The Sugarland Express. It was a relatively low-budget film produced at practical locations in Texas. Memorable dialogue scenes were filmed in a car being driven down a road in Texas. Panavision founder Robert Gottschalk personally brought the first Panaflex camera to Zsigmond while the film was in production. The new camera enabled Zsigmond to shoot synch-sound scenes in the car while panning as much as 360 degrees. That enabled Spielberg to put the audience in the car with the characters as it sped down the road

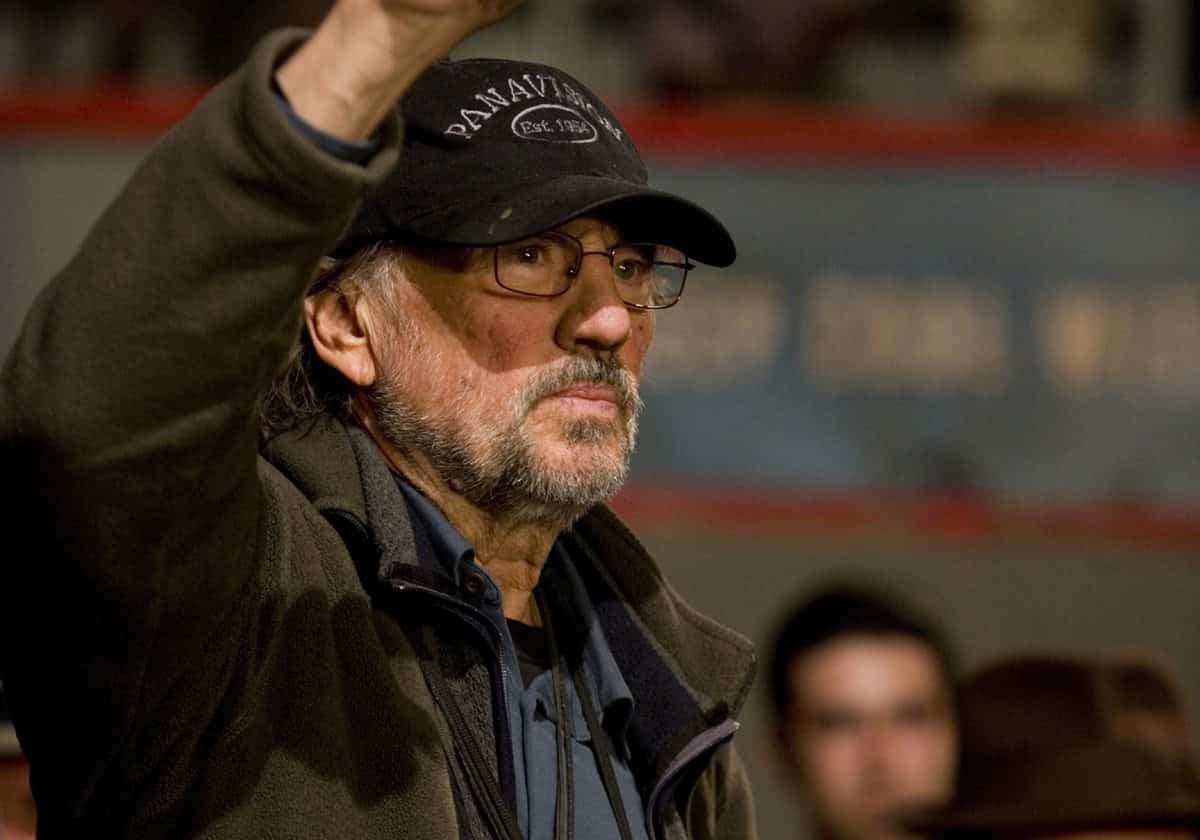

Three years later, Zsigmond and Spielberg collaborated on Close Encounters Of The Third Kind. It began as a low budget film and evolved into an epic blockbuster. The unforgettable ending occurs with a space ship landing. The door opens and aliens step onto the surface of the Earth. That unforgettable scene was filmed in an airplane hanger in Mobile, Alabama, where the temperature soared as high as 120 degrees Fahrenheit. Costs were also soaring as Zsigmond brought lamps and crew from around the country to light the darkness inside the hanger, which was extended with some 200 feet of tenting. Spielberg resisted studio executives demands that Zsigmond be fired.

Close Encounters Of The Third Kind grossed some $300 million dollars at the box-office, Zsigmond won an Oscar, and the film earned seven other nominations. “It was like a dream come true when I heard them call my name,” he reminisced. “I still remember walking up those steps knowing that 80 million people around the world were watching. It was the first time I felt I belonged. I thanked Gyorgy Illes and my teachers in Hungary who taught me to think about film as art.”

His comments resonated with students, teachers and the general public in Hungary. I interviewed Zsigmond for the first time the following year about his experiences filming The Deer Hunter. At the end of our first conversation, he said, “There’s another cinematographer who you should be writing about. His name is Laszlo Kovacs. He just finished shooting F.I.S.T.. It’s a wonderful film.”

That became a ritual. Vilmos ended interviews by suggesting I write about a film Kovacs shot, and Laszlo always urged me to write about Zsigmond’s latest film. Zsigmond earned other Oscar nominations for The Deer Hunter in 1979, The River in 1984 and The Black Dahlia in 2006. In 1993, he won an Emmy award for the television movie Stalin. He is the only cinematographer with Oscar and Emmy awards.

"I still remember walking up those steps knowing that 80 million people around the world were watching. It was the first time I felt I belonged. I thanked Gyorgy Illes and my teachers in Hungary who taught me to think about film as art."

- Vilmos Zsigmond ASC

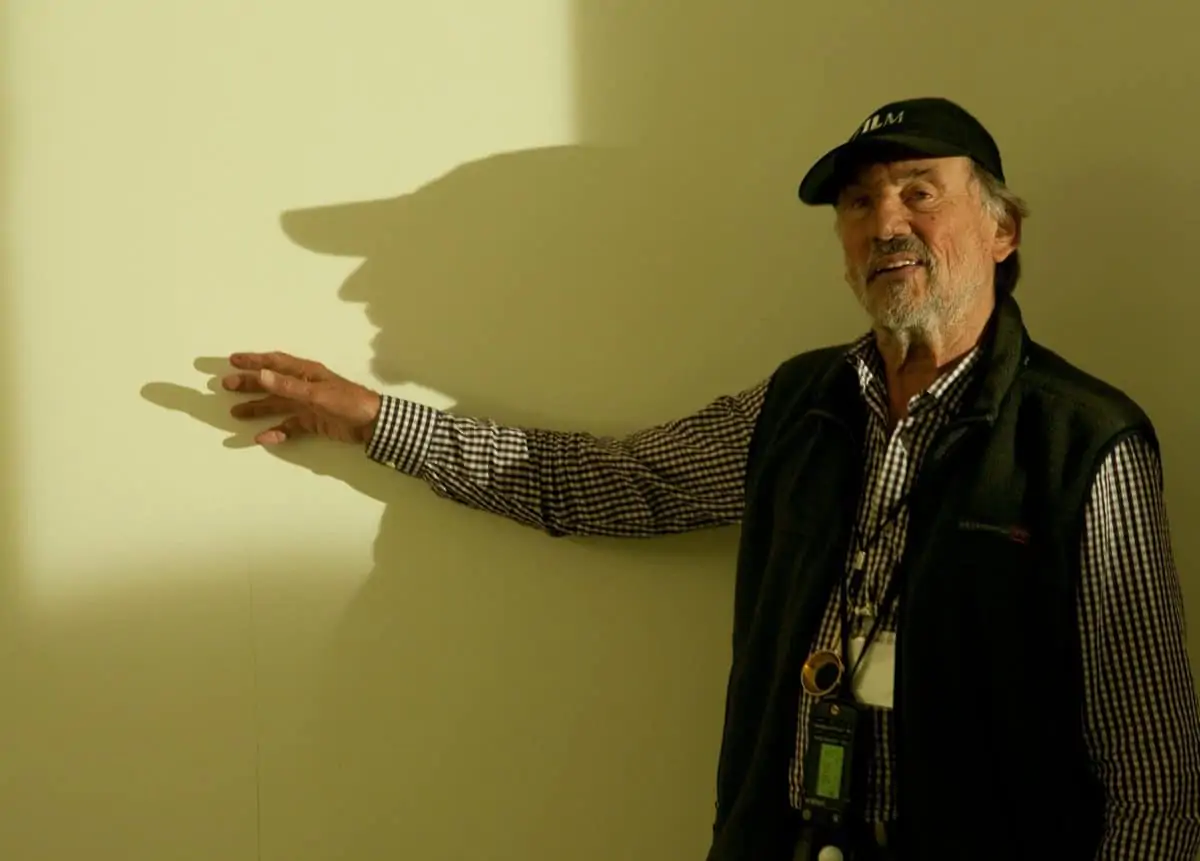

Zsigmond and Kovacs never forgot their roots. In 1989, they established a two-week summer Masterclass at their alma mater in Hungary. Student filmmakers from around the world were invited to participate every other year.

I witnessed and wrote about the 1999 Masterclass. People stopped us on the street and asked Vilmos for his autograph. Tibor Vagycozky HSC, who was Zsigmond’s classmate explained, “They were inspired by his speech at the Academy Awards.”

Zsigmond received Lifetime Achievement Awards, respectively from CamerImage in 1997 and the American Society of Cinematographers in 1999.

The final chapter of this story is still being written. Last year, Zsigmond shot companion independent films, Louis and Bolden!, about the dawn of the age of jazz and blues music in New Orleans during the first decade of the 20th century.

The scripts for both films were co-authored by director Dan Pritzker, a musician who took his first turns at the helm on these simultaneous productions. Bolden! is the life story of Buddy “King” Bolden, a musician who created a new kind of music on the streets of New Orleans. Louis is the story of Louis Armstrong, who was inspired as a child when he saw and heard Buddy Bolden perform on the streets of his hometown. It’s a nearly B&W, silent film with original music created and played by Wynton Marsalis. Louis premiered at Camerimage last year, where Zsigmond was given a standing ovation. A release date is being set for Bolden!