CALL OF THE WILD

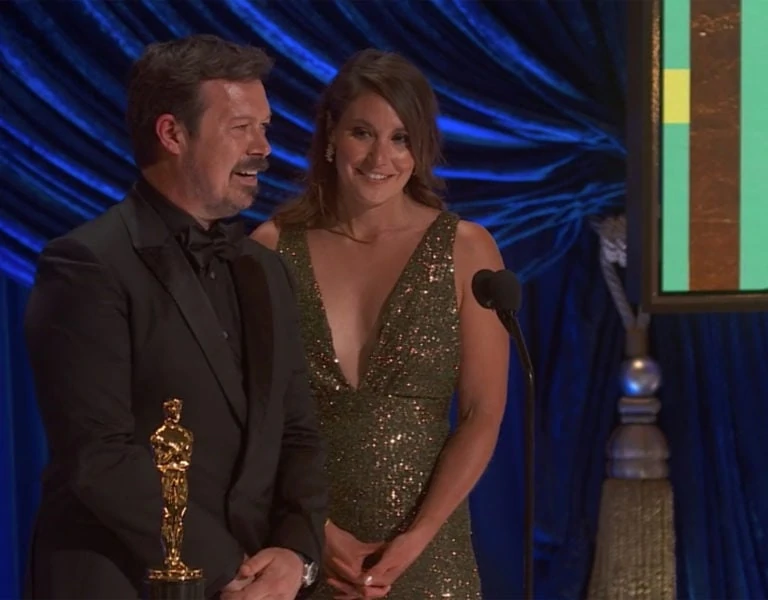

When Alex Pritz was shooting his debut film, The Territory, in the Amazon jungle, he probably didn’t expect that he’d end up sharing the role of cinematographer with one of his documentary subjects. But teacher-turned-DP Tangãi Uru-eu-wau-wau was up for the challenge, and the result is one of 2022’s most extraordinary pictures.

“Dragons eat the forest, now nothing will grow. And those who live within it, where can they go?”

Environmental activist Neidinha Bandeira has devoted the last four decades of her life to championing Brazil’s Indigenous communities. It’s a vocation that puts her firmly on the frontline of conflict, as their Amazonian reserves are encroached by settlers. In Alex Pritz’s documentary, The Territory, her lullaby of lament encapsulates the despair of the Uru-eu-wau-wau, an Indigenous people in Rondônia fighting not just for their homeland, but for their culture, identity, and existence.

It was hearing of 63-year-old Bandeira’s tireless fight that first drew Pritz into the lives of the Uru-eu-wau-wau. The environmental science graduate had brought his passions for conservation and the natural world to photography and photojournalism, before expanding into documentary filmmaking. A fan of Bandeira’s “badass” work, he reached out to her over email and she put him in touch with Brazilian producer Gabriel Uchida. Together with filmmaker Will Miller, they formed The Territory’s original production team.

“As soon as it became obvious that the Uru-eu-wau-wau were going to be part of the film and that there was a strong potential story, we as outsiders and non-Indigenous people felt like we had a lot of work we needed to do to understand how to engage with this group in a way that felt equitable and just,” Pritz explains. “We did a lot of research and reading around that, especially.”

That story focused on 18-year-old Bitaté Uru-eu-wau-wau, voted by the community’s elders to lead the defence of their territory. He’s a youthful symbol of Brazil’s Indigenous resistance, spearheading the Uru-eu-wau-wau’s sophisticated surveillance team which keeps tabs on the regular infringements on their rainforest home. Bandeira works closely with them, using drone technology which gives them a bird’s-eye view of the pock-marked Amazonian landscape bordering their land. The scarred earth is a gut-wrenching sight that hammers home The Territory’s cause.

SHIFTING LANDSCAPE

To prepare for the shoot, Pritz threw himself into researching the Amazon’s history and learning about Brazil’s rich past of participatory cinema. He highlights the work of Vincent Carelli and his Vídeo nas Aldeias (Videos in the Villages) programme, which strengthens the identity of Indigenous groups through the medium of film.

Filming took place across three years, from 2018 to 2021, and Pritz’s team took eight trips to Brazil, each lasting between three weeks and three months. During that time, they embedded themselves in the Uru-eu-wau-wau’s way of life, even sleeping in hammocks.

The production saw seismic changes in Brazil’s political and cultural landscape. In 2019, Jair Bolsonaro became the country’s president; a victory that would catalyse the illegal invasion of Indigenous land. Then, 2020’s Covid outbreak would turn Pritz’s shooting plans on their head.

Step forward, Tangãi Uru-eu-wau-wau: ordinarily a teacher in the local school, the 28-year-old would become The Territory’s new cinematographer in Pritz’s Covid-enforced absence. “He had a really keen interest in films,” explains Pritz. “He had watched several of them. Being a teacher, he’s very open, very curious and very eager to learn, but also took it upon himself to teach himself as much as he could about cinematography. I think he’s an amazing artist.”

Tangãi remembers his impromptu entry to filmmaking: “One day Alex Pritz came to my village and he let me take the lead on the shooting. I had the opportunity to express my own ideas since I was directing the scene. It was great because it opened a new path, so I could learn even more throughout the production.”

The Territory was shot on Sony cameras; the FS7, FX9 and FX6 for Pritz’s work. Pritz paired them with 35mm and 50mm Sigma lenses for shooting both the Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau and the settlers, but also occasionally used a ZEISS 21-100mm zoom for the latter.

When Tangãi and his community took over, they opted for Sony Handycams. The footage was shot S-Log3 for colour-matching purposes, and the Handycams’ two XLR inputs apiece meant they could use a shotgun microphone and a wireless lav on each device.

For the rookie cinematographer, the biggest challenge was carrying the equipment around. “These are heavy things and I also had to bring my personal belongings, so it became a great weight,” Tangãi says. “Sometimes we even had to climb trees and it was a hard task. But at some point, I started getting used to the heavy backpack and made better choices when deciding what to bring or not.”

PERMISSION TO FILM

Not unexpectedly, the Uru-eu-wau-wau people were initially sceptical of being filmed. “And rightly so,” says Pritz. “It was a long, slow and patient set of conversations to be able to work with them. The elders in this community had never seen a feature film before, so how do you start a conversation on whether somebody wants to be part of a film if they’ve never seen one? That began this whole process of research and trying to understand what the best way to do this was.”

They decided to let the community get hands-on with the equipment to see for themselves how the art of the filmmaking worked. “We brought some small cameras with us on the first couple of trips and said: you interview me, I’ll interview you – let’s flip these power dynamics and have you guys feel what it’s like to hold a camera. It felt like a really important conversation, to take it slow in the beginning – especially for a community that’s been so stereotyped and stigmatised, and had such racist depictions in the past in the media.”

Each time the production team wanted to come to the village to film, they had to ask permission anew. Representatives from each of the six villages had to come together and come to a decision as to whether to let the filmmakers in – a process which could take hours, or even days.

The process was a little easier for Tangãi, but not without its challenges. “Before every single work I spoke to my family and explain to them how it’s going to be like,” he says. “Sometimes there were a few of them who didn’t want to be filmed, but I explained its importance and they understood me. At a certain point they got used to it and it was as if I wasn’t even there with the camera. We all learned from this process and my family wants to see my growth.”

Although Pritz is a vocal supporter of the Uru-eu-wau-wau cause, The Territory also shines a light on the community’s rivals: the Amazon’s settlers. Ingratiating himself with this group was tricky. “They felt maligned by the media, as though people were painting them as these cartoon villain characters when really there’s a lot more to them,” he explains. “They saw themselves as these heroes of their own journey, the pioneers going out an creating something out of nothing. Over time, I was able to build a relationship with them. I spent as much time filming them digging holes in the hot sun as I did out cutting down the forest, and they felt like that was a more accurate balance of their lives. They let me in in a way that I didn’t fully expect.”

FRAMING FRAGILITY

Pritz’s approach to composition was to stay wide, especially with Bitaté and Bandeira. “Part of that was to be able to get some layers in the shots and be able to have some depth,” he notes. “That was something we talked about – how to show, there’s so many different characters in the film, you rarely see two of them together in the same frame. We wanted to be as close as we could when they were with people, but also trying to build in some of those relationships in other ways, even if they weren’t in the same frame together.”

The team’s lighting kit was limited, often relying on practical sources – such as the settlers’ headlamps – for an atmospheric glow. In one tragic scene, when the rainforest is set alight by settlers, the frame is filled with an amber glow as Pritz captures the destruction first-hand. “The whole sky becomes quite hazy, and the lighting becomes really soft and actually quite beautiful, in spite being really sad,” he says. “It’s like there’s a softbox on the whole sky.” This was also one of the most difficult scenes for Pritz to capture, both emotionally and physically, as he had hiked for seven hours into the forest to see it.

In the grade, colourist Seth Ricart drew out the Amazon’s vivid colours, from its trees to the creatures that call it home. For Pritz, it was important for the audience to know from the first couple of frames which side of the forest’s story was being shown – the Uru-eu-wau-waus’ or the settlers’. “With both the sound design and the colour, we wanted to have it a different palette for the two different sides of the story. So, bringing a lot of blues into the Indigenous storylines, bringing a more parched, desaturated, dry, greyish look to some of the invader scenes,” he adds.

A scene from Knives Out proved the unlikely inspiration for one of Pritz’s proudest moments from his lensing of The Territory. In the 2019 mystery film, Ana de Armas’ character is seen walking out of the house after everything has fallen apart, and the camera pans down with her smoothly – until, that is, the rest of the family rushes out of the house and the commotion follows her. “[The camera] picks up off the tripod and enters this chaotic, handheld movement until she gets into the car, then it moves back into a more static place,” he explains. “I thought that was so creative.”

In the opening scene of The Territory, Pritz uses a 24mm prime lens on the FX6 to move from a macro shot on some leafcutter ants to join some of the Uru-eu-wau-waus’ children as they run to the river. “I wanted to connect people, the environment, animals and children, and that felt like a good way of doing it.”

While filming on the frontline of the fight for the Amazon, did Pritz ever feel in danger as a cinematographer? “Definitely. We felt that very often. We were in these tiny towns with a hundred people… Everybody knows everybody and you get followed. You know when you’re being followed because you get photos of yourself – the back of your head – sent to you from numbers you don’t recognise. There was always this sense that you’re being watched, and a wrong move would mean trouble is the sort of message that’s being sent to you all the time.” But he’s quick to acknowledge that any danger he faced is nothing compared to what his documentary subjects and other Indigenous peoples face day in, day out.

For Tangãi, shooting for The Territory might just be the gateway to a new career. “I learned so much about filming, storytelling, scenes and action, and I hope to put all of these together, maybe in a few years. I know there are many difficulties, but I hope to form an indigenous team to work together and produce our own film – that’s my dream. Maybe in the future I’ll look back to this interview and remember the first steps to a film directed by me.”

The Territory is released in cinemas on 2 September.