Technical Master

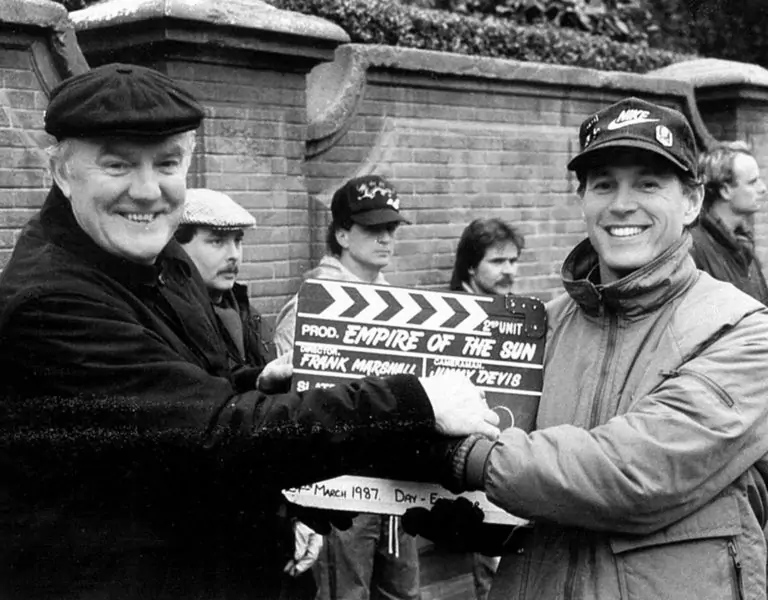

Clapperboard / Alec Mills BSC

Technical Master

Clapperboard / Alec Mills BSC

BY: David A. Ellis

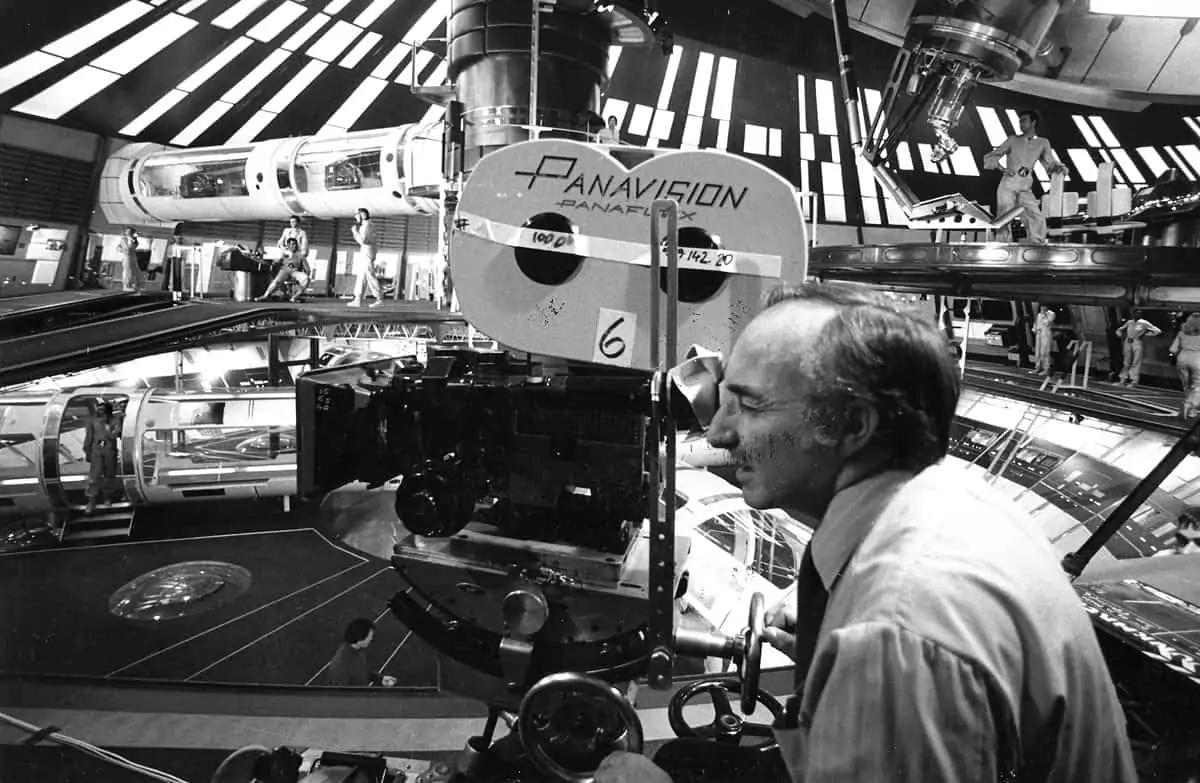

Notable cinematographer Alec Mills BSC has been responsible for the look of many well-known movies, which include The McKenzie Break (1970), Death On The Nile (1978), Return Of The Jedi (1983), Christopher Columbus (1992), and worked on no fewer than seven 007 James Bond films. They include: On Her Majesty’s Secret Service (1969, DP Michael Reed BSC), The Spy Who Loved Me (1977, DP Claud Renoir), Moonraker (1979, DP Jean Tournier), For Your Eyes Only (1981, Alan Hume BSC), Octopussy (1983, DP Alan Hume BSC) as camera operator; and The Living Daylights (1987) and Licence To Kill (1989) as the cinematographer. Later in his career, he even tried his hand at directing.

Born on 10th May 1932, Mills had a keen interest in the cinema as a boy. On leaving school at fourteen he was fortunate enough to get a job in a small studio called Carlton Hill Studios, Maida Vale, as a tea boy, later as a clapper/loader. He enjoyed his time there and stayed for three years. Carlton Hill specialised in B-movies. Eyes That Kill (1947), The Monkey’s Paw (1948) and Vengeance Is Mine (1949) are some he recalls.

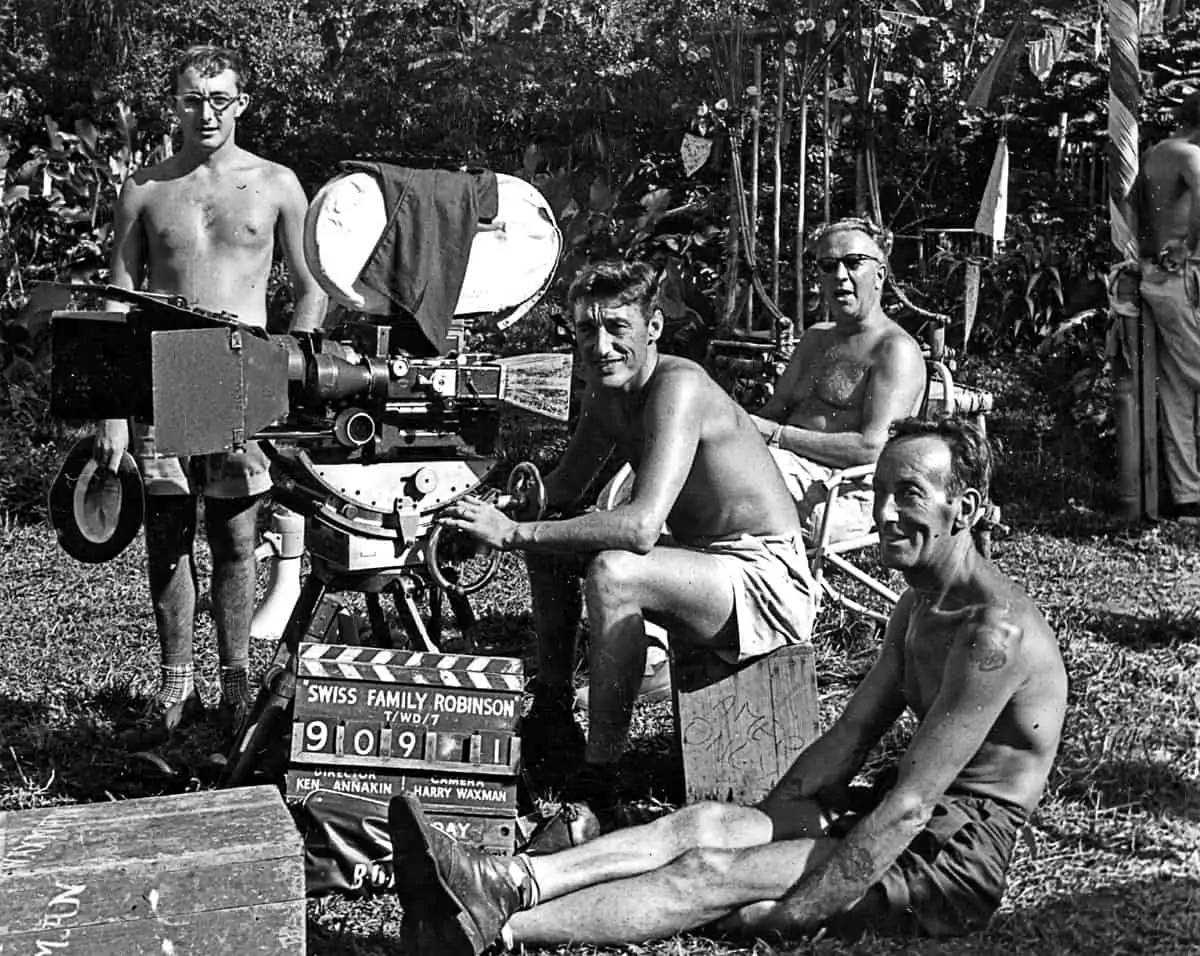

Mills left Carlton Hill to do national service in the navy. On his return he went back to film, and worked on several movies with cinematographer Harry Waxman BSC, from whom he says he learned a great deal.

In 1955 Mills became the focus puller on Contraband Spain, followed by Lost (1956) with Guy Green directing, and Waxman as the cinematographer. Along with features, Mills also worked in television. His first major production as a camera operator was when Michael Reed gave him a break in 1966 on The Saint series.

Asked what TV was like compared to features, he said, “TV is more demanding because they have smaller budgets, meaning you have to cover more pages in a day. On Soldier Soldier we had to do about eight pages a day. Episodes usually took a week, occasionally two.”

His favourite TV series was The Saint shot on 35mm. The first time he worked on 16mm was on Press Gang. Soldier Soldier was also on 16mm.

In 1969 Mills operated on his first Bond, On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, with locations in Switzerland and Portugal.

He said, “Principle photography on a James Bond film usually takes around six months. There are several units. First, second and model, and sometimes flying and underwater units, all of which have at least one camera operator. Location work can be very tiring.”

He remembers that six months of concentrated filming on Licence To Kill at Churubusco Studios in and around Mexico City was very draining. Not to mention the very humid conditions he experienced in Florida Key West. Even when that was finished there were still six months of editing, but that didn’t involve him until the final grade, which usually took a few days.

Did he enjoy all working on the James Bond pictures? “Yes, every one. What a wonderful company Eon Productions are. Barbara and Michael, and the late Cubby, were like a family to me. And they don’t forget you, even after years of retirement.”

Mills became an associate member of the BSC in January 1977, becoming a full member in 1984. He was on the board between 1998 and 2009, and acted as vice president from 2002-2009. He was also chairman of the GBCT from 1978 until 1980/81.

He went up the ranks and became the DP on The Island Adventure (1982). He said that the first job as a DP is always scary, but on this film he was working for free for producer Stanley O’Toole, to get a credit.

Mills worked for Disney as a focus puller and later as an operator. He said, “I was focus puller on several, including Kidnapped (1960, DP Paul Beeson BSC), Greyfriars Bobby: The True Story Of A Dog (1961, DP Paul Beeson BSC) and The Moon-Spinners (1964, DP Paul Beeson BSC). I operated on Guns In The Heather (1969, DP Michael Reed BSC) and Diamonds On Wheels (1973, DP Michael Reed BSC), which was mostly around Pinewood. I did nothing in America for them.”

Regarding challenging movies, Mills said Roman Polanski’s Tragedy Of Macbeth (1971, DP Gilbert Taylor BSC) was particularly exacting as an operator, both mentally and physically. His most challenging as a cinematographer though, was Shaka Zulu, a ten-part TV series, shot entirely in South Africa. It took a year. However, it was a very useful production for him, because “Cubby” Broccoli had seen it in America. He offered Mills The Living Daylights, which led to his return to the Bond team.

"Confidence is essential in all things, even if internally you are very nervous. We all feel nervous at times and it is not made any easier by tight schedules and limited budgets. But we can’t show it."

- Alec Mills BSC

Did he choose the second unit DPs on the 007 movies? “Sometimes. Arthur Wooster BSC was long-established, and was well-known for his action photography on the Bond films. And James Devis BSC was always a pair of safe hands on second units.”

Speaking about Mills, Devis said, “I first met Alec at Pinewood in the early 1950s. We spent about nine happy years there and we became friends for life. Whatever grade Alec was in, he was always an efficient, dedicated film enthusiast and very popular with the whole crew. I was fortunate enough to have his son Simon as my first assistant for several years, who is like Alec in his work ethic. I do not know what I would have done without him.”

Mills would often source equipment from Samuelson’s. Recalling his dealings with Mills, Sir Sydney Samuelson said, “This excellent technician has been known to me for as long as I was developing a company to supply camera equipment. This eminent British cinematographer has so many iconic films to his credit and, in my view, they have all hugely benefited from the sheer professionalism of attitude and technical expertise of Alec Mills BSC.”

Mills said he learned a lot about lighting from the likes of Jack Cardiff BSC, Jean Tournier and Michael Reed BSC. “Confidence is essential in all things, even if internally you are very nervous. We all feel nervous at times and it is not made any easier by tight schedules and limited budgets. But we can’t show it,” he said.

Asked about shooting greenscreen, he said he didn’t use it much, as it was specialist work at the time. He says he preferred not to use it, saying it was much nicer to see what he was filming, rather than imagine what it would look like later.

Mills’ industry heroes include Harry Waxman and Michael Reed. “They had influence over me in so many different ways. From a directorial point of view it was probably Roman Polanski who challenged me most.”

Mills says that he kept the same crew as much as possible. For many years Danny Shelmerdine was his clapper loader, Mike Frift his focus puller, then Frank Elliot. After getting his break on the Bond films as cinematographer, he was delighted to use Mike Frift as his operator. His gaffers usually came from the old school. He worked with John Tythe, Roy Larner and Geoff Chappell, who for so many years serviced and maintained Mills’ light meters.

Looking back to shooting on celluloid, did he have a favourite film stock? “As I recall most of my films were shot using Kodak. I found Kodak never let me down.”

Asked about his experience in directing, Mills said, “The producer who gave me my break as a director was Stanley O’Toole, who gave me my break as a cinematographer. He offered me the opportunity to direct two horror films, Bloodmoon (1990) and Dead Sleep (1990). I always wanted to direct, so it was a golden opportunity to see if I was capable. The scripts were awful, but I put a lot of work into the projects. All things considered, the end result was much better than I could have hoped for.”

Mills’ last film as a cinematographer was The Point Men (2001). He taught cinematography between some of his movies at the National Film & Television School, and again after his retirement from a very successful career. He said, “It was nice to be involved after I retired, as this was an opportunity to pass on years of experience.”

He said his advice to newcomers would be very little, except to be honest and learn to from your mistakes.

Like several others before him, Mills has recorded his time in the business in a 256-page book entitled, Shooting 007 & Other Celluloid Adventures (ISBN: 9780750953634), published in 2014 by the History Press, with a foreword by the late Sir Roger Moore.

But the tale doesn’t end here for a man whose cinematographic talents and persona are woven into the very canvas of British cinematographic history. Mills is currently writing another volume.